It was my Pearl Harbor Day, only I had no FDR to rally me with fireside chat to encourage a heroic comeback. Nevertheless, like USS Arizona and Utah, I lay immobile from what felt like a sneak attack. In the dim quiet of the calculatingly sterile room I was alone, awash with discouragement and sunken in the icy depths of depression. My head jerked to the side repeatedly, unpredictably and uncontrollably, to my chagrin. This was the onset of the “tic” that would haunt me for years as a foreboding precursor to “events.” Whether its genesis was a reaction to a prescriptive magic bullet-esque capsule I obligingly swallowed every morning and evening or had some more organic cause, I was yet to discover. In that moment, in that mental-ward room alone, I felt I was the helpless target and it was my enemy bent on my destruction.

A frosty chill had settled in my bones: a hybrid sensation of both fear and humiliation.

Emotionally and physically spent, each time my thoughts would calm I’d begin to drift… then the tic would prevail and snatch my serenity away, and with it, my hope to escape the horrific reality of being locked in the “nuthouse” known as 2-West. Scuffling whispers echoing in the hall and in my brain halted, followed by a brief but sacred silence. Broken in a breath by the obnoxiously loud latch, a shadowy figure entered the room. The voice was comfortingly familiar.

Dr. Hayes pulled up a chair to my bedside. I’d been drugged by my well-meaning captors and incapacitated by my depressive symptoms, which had attacked my cognition and ability to articulate. I now stammered. Choking on my words, I gasped for air and grasped for hope. The tic manifested again and again. The doctor sat there and watched. My eyes begged and wept, as I craved an explanation for it.

Her reply was sincere and insightful (I now realize), but in that moment, it was simply an added frustration and offered no solace. Her response, “It is what it is,” was abstract. I needed concrete answers. I thought I would find them here in a house of science; get them from a woman of medicine. I was wrong and hope was fading. The universal truths of “Acceptance” and “Mindfulness” were light-years away from this black hole of melancholy in my chest sucking every atom of energy away. My mind seemed to be imploding as every glimmer of light left me. All I could muster was a vague semblance and facade of normalcy. But the tears and terror betrayed me, at least in front of Dr. Hayes. “Be patient,” she said with no appreciation for the pun. “It’ll get better.” She patted my hand and brushed my hair from my face. For a moment, I felt a tinge of comfort, but it quickly faded.

“I’m sinking, I whispered.

“I’ll check back in with you,” she said, as she turned to leave. In that moment, I felt we were both over our heads; her, beyond her expertise and me, out of my mind. And so, I was left alone in the dark, amid reminiscence and wonder… how I got here and if there was anything, at all, beyond the shadowy veil that obscured my future.

I was the middle child, the “lost child” of four, only 10 ½ months younger than my older sister, and just 2 ½ years between my older and younger brothers. We weren’t just “sandwiched” together, our house was a friggin’ sardine can! Hindsight being as perfect as it is forgiving, I saw myself as an imposition from the get-go. My mother made that abundantly clear when she referred to me as “an accident.” Had I gone to my doctor six weeks after giving birth and learned that I was pregnant again, I know I’d have struggled, too. However, that empathetic revelation came to me only after having four children of my own in quick succession. To my child’s mind, “an accident” felt like “less wanted,” and “less wanted” was merely a gnat’s breath from “unwanted” and “disposable.”

A preemie adrift in a sea of secondhand smoke with callow navigators parenting made for the perfect storm. A castaway in the hospital with pneumonia five times from age three months to five years, my only “rescue” was as an infant (presumed to be at death’s door). A zealous trio of nuns scooped me up, whisking me off to the chapel for a “quickie” baptism. All was well after they sprinkled me (to assuredly avert adding this one to the rolls of innocent uncovered souls in Limbo). My parents were livid, but I was “saved.”

Imprinted on my psyche, just like a hatchling, the images of people in white coats permanently became those of predators and perpetrators of pain. The middle of the 20th century for me was not a quaint, “vintage” period of pink or turquoise kitchen appliances, but rather a reoccurring nightmare muddled with separation anxiety, guilt and abandonment. The logic of my child’s mind turned the reoccurring trauma into a life lesson: Never be sick, for when you are sick, you are less than perfect. When you are less than perfect, you disappoint people and they will, in turn, abandon you.

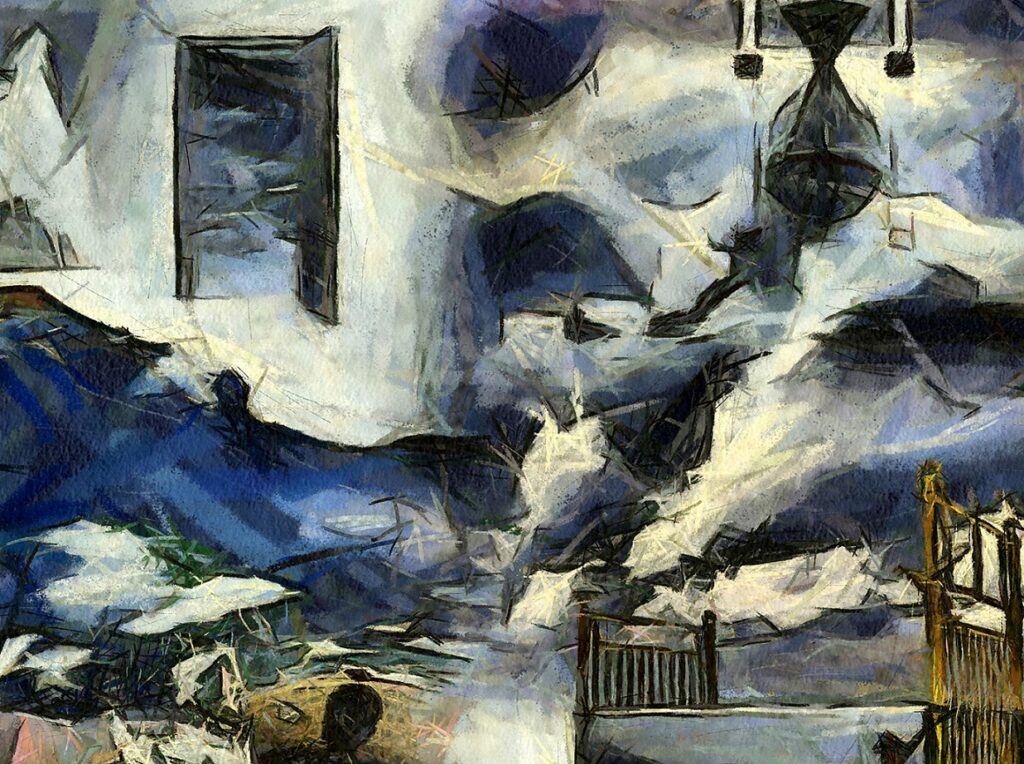

It was upon this ethos that I operated for the next forty years. Always putting the health and welfare of my family before my own, I’d become a human sponge, absorbing responsibility for everyone’s happiness while the weariness within turned to desperation. I became hollow, echoing affirmations to keep the darkness at bay. The tempest that was my conscious mind was swallowed in exhaustion and cradled in despair. My ethos, however, urged me on. Constantly fortifying my walls of normalcy with regimen and regulation; against the overwhelming fear of abandonment, my imagination was suppressed and soul dismissed.

In reflection, marrying a relative stranger at age 19 was ill-advised, but like so many adolescent girls (especially those in love with love and saddled with abandonment issues), I would’ve rebuked Christ, Himself, had He warned me not to go there. I was the proverbial imbecile in the horror flick who just has to check out that mysterious noise in the basement, and, yes, it was a dark and stormy night. Reasoning with an adolescent is like talking to a drunk. They nod in reluctant compliance, go ahead and do the most idiotic things, then in the light of the new day comes denial that a warning ever came their way. Like both the drunk and typical teenager, I looked for a scapegoat, someone to blame for my unhappiness. I didn’t have to look far. Jim had served well as that perfect scapegoat for nearly 21 years. His penchant for raging, berating, and blaming became legendary. His choice of substances with which to self-medicate and mitigate his woes varied, but, at the end of the day, it didn’t matter. When we divorced, I was left without a banner of blame to march under. The weight of personal accountability for my own grief toppled the facade of “perfect wife and mother,” and collapsed the assumed-identity of Martyr Mom I’d constructed.

So, as the sunlight sliced through frosted stale windows, the shadows of their bars danced a tarantella of mockery on my morning. The medicated fog was lifting and the realization of my life in shambles felt like a millstone. The ear-piercing decibel reach of the PA system announced the arrival of the morning gravy train. My ambition and appetite were well into the deficit range as I emerged from my room. A technician was standing at the nurses’ station with tool belt awkwardly sagging. The nurse pointed in my direction. I stepped aside and together they entered the room. As the door latched behind them, a wave of vindication wafted across my funny bone as I remembered indignantly placing a bed pillow over the single-eye surveillance camera near the ceiling before retiring the night before.

Having someone else on whom to heap the responsibility and blame for all my ills and misfortune had been my go-to and convenient truth. Unfortunately, Jim had been gone for a year and I was left with the fallout and responsibility for cleaning up the mess, now MY mess. Financial, emotional and mental stability was mine to discover and maintain. Although there was glorious serenity in not having to jump to alert at the sound of his truck pulling into the driveway, and an equally splendid satisfaction in clearing out his toys and trophies, clearing the emotional carnage of two decades was a challenge I had yet to face. It was like the fine volcanic ash following the eruption of Mt. St. Helens. Shoveling and sweeping away the bulk of it allowed for an appearance of normalcy, but it was insidious and found its way into every crevice imaginable. Whether under a carpet or in the folds of a dream, gritty reality would reappear countless times and have to be dealt with.

The night flew furious and loud, with ward newbies on suicide watch; the heavy doors creaked and slammed on the hour. The tic kept me company, if not grounded in the reality of this surreal happenstance.

The previous day and evening had exhausted me. In this place of so much agony, all I felt from professionals was condescension. What I yearned for was some validation and some valid explanations. Dr. Lueong had pronounced me as “Bipolar,” but that only raised more questions than it answered. Communication, I’ve always felt, was a sign of respect. There was so little direct communication and interaction (other than with my peers) that I felt justified in keeping my secrets, my thoughts and feelings hidden beneath the pretentious masque of normalcy and obedience. That was what was expected and that was what was deemed “perfect,” at least “perfect” enough for my “Get Out of 2-NW Free” card. I interviewed from behind the turret of fabrication and was disappointed when it was not even questioned. I chose to feel safe in my exit strategy and the professionals appeared to feel safe choosing not to question the quality, texture or durability of the fraudulent fabric I weaved.

They sent me home, on my own that Super Bowl Monday morning with a ticket to ride mass transit and no assurance as to where my path would lead; no Thomas Guide for sanity. I was as “stable” as either Crystal or Andrew (my ward-mates and co-conspirators), but none of us were really “safe.” Safety and security abide in trust and in knowledge. I was ignorant about mental health and filled that void with all experience had taught me: The Fearful Ethos. “Never be sick, for when you are sick, you are less than perfect. When you are less than perfect, you disappoint people and they will, in turn, abandon you.”

My path forward was erratic. It would include many more hospitalizations, interventions, stern looks and reprimands. To death’s door and back numerous times over. Prescriptive talk and tablets, conversation and caplets would be the stuff I’d build safe boundaries out of for nearly two decades. But, although rescued from would-be demise, I would never be sound enough to perform as before.

My recovery allows me to observe the past and emerge unscathed, not dwelling or immersing myself in the mire of guilt and shame, but rather celebrating the successful, strengths-based life I’m now living, moment by moment, and breath by breath. The Past is a universal reference library which warehouses wisdom, our own and the vicarious victories of others. It’s a marvelously rich place to visit, but it was never intended to be a place to abide for a lifetime.

My first mental-ward stay would not be the last. At last count… I lost count. Fortunately for me, I’ve learned much from my experience and vicariously from my peers. I’m able to re-frame experiences as significant episodes in my life, emblematic of the incarnation of my former self. I have no shame in it, as I consider surviving to tell the tale to be a badge of honor.

I now know that the “tic” that tormented me has a name (tardive dyskinesia or “TD”) and was caused by psychotropic medications. I’ve managed to re-frame its manifestation (much less frequent today, as I manage stressors and am prescribed no psychotropics). Today I see the TD as a bellwether calling for me to deal with excessive, internalized stress in order to prevent symptom exacerbation. It’s a gift, albeit of the white elephant variety. I’ve learned from each adventure and each misadventure and gained experiential wisdom to move forward. I see history as a gift, too, while dwelling there is a fool’s errand. History is what it is: a moment in time and an opportunity to see the present in perspective.

This is such a well written piece, I hope you keep writing. You sound empowered, incredibly strong and brave. The way you talk about your experiences within the hospital system articulates exactly how I felt about it. Are you still dealing with TD symptoms?

Report comment

I agree, you are a good writer. And I’d love to see a link to your visual work, Lindsey.

“I see history as a gift, too, while dwelling there is a fool’s errand. History is what it is: a moment in time and an opportunity to see the present in perspective.”

I would describe myself as in the – still working our way towards wisdom – phase of life. (I’m right now dealing with a real estate sale that has seemingly ripped my extended family to shreds, due to greed, so am rather sad this Christmas season … but trying not to be. “The love of money is the root of all evil.” And I’m sick to sh-t of the unbridled greed – especially given the fact that our un-Constitutional banking/monetary systems are about to implode.)

Maybe we should be discussing our society’s real problems, in real time – rather than having insane people, who believe all distress is caused by their made up “chemical imbalances in the brain” and “mental illnesses,” and cured with their iatrogenic illness creating neurotoxins – in charge instead?

Personally, I’m quite certain it is greed, or “the love of money,” that is destroying Western civilization. And a proper and timely discussion of the Ponzi scheme that is the British, Vatican, and US monetary system is in order … not to mention the scientific fraud of their “bullshit” psychiatrist’s crimes.

Let’s hope and pray we all learn to live in the present, so we may fix our society’s systemic problems, in an expedient and productive manner for the majority, rather than just the 1%.

Report comment

My own mental illness appeared in the 1980s so I know exactly what is being spoken about here although I am blessed to have a better experience in hospitalizations. I am currently doing much better with the help of a most wonderful counselor and am trying to safely take myself off meds which I believe I do not need. Along the way I developed restless legs and discovered the med prescribed for this bi polar condition that everyone seems to have most likely caused the RLS. I have been able to gradually and safely stop the Requip and guess what what!! The RLS is gone. Completely gone. So now I aim to take myself safely and slowly off a couple other meds I think I don’t need. We are blessed to have people speak the truth of their own experiences and help other. I am so glad I discovered these writings and the research.

Report comment

What a remarkable uplifting essay. Thanks for putting Christmas alone into perspective.

Report comment