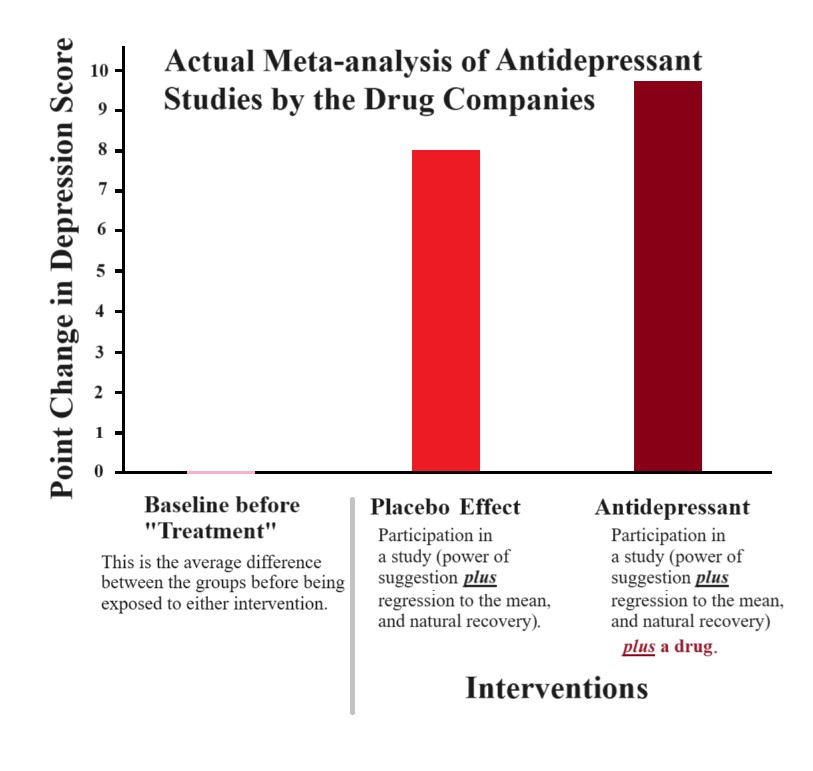

Based upon the 2022 meta-analysis by Stone, et al., a difference of 1.8 points on a measure of depression between placebo (average depression score reduction of 8.0 points) and antidepressant (average depression score reduction of 9.8 points) was found. This statistically significant difference is so small it is undetectable in real life; it is not even an average small, clinically insignificant difference. (This is explained in “Understanding the Limits of the Beneficial Effect of Antidepressants Reported in the Meta-analysis by Stone, et al.” on Mad in America.) This clinically insignificant difference is only detectable in a large sample.

Indeed, some research has found little difference between placebos (which include the power of suggestion, regression to the mean, and natural recovery) and just regression to the mean and natural recovery.

Natural Recovery

Because depression tends to ameliorate over time, a group of individuals chosen to participate in a study because they display symptoms of depression will, on average, appear to improve with no intervention other than the passage of time. This is natural recovery. And it can be quite substantial with one study finding that as many as 85% of untreated depressed patients recovered.

Regression to the Mean

Furthermore, depressive symptoms fluctuate even among those individuals who tend to suffer from persistent depression. Thus, when chronic sufferers are included for participation in a study because, on average, they deviated from the general population by exceeding a minimum depression score, because of symptom fluctuation and the imperfection of the depression measures (which means there is some fluctuation in scores even if retested immediately), some will no longer exceed that minimum at a later point in time. The average for the group as a whole will thus “regress toward the mean” of the general population and thus the group will appear to get better. Again, this occurs with no intervention other than the passage of time.

Adding the Power of Suggestion

The apparent impact of placebos includes natural recovery, regression to the mean, along with the added effect of the power of suggestion due to being in a study of treatment specifically for depression. Antidepressant treatments include all of these plus the administration of a drug.

Statistical significance between average measures of large populations (an 8.0 point vs 9.8 point reduction on a 52-point depression scale) can be fundamentally unrelated to an effect that is discernable in real life. The impact of something that can’t even be discerned cannot be meaningfully or clinically significant.

The Power of Suggestion: What My Experience with Hypnotism Taught Me about the Placebo Effect

When I was in high school, I experimented with hypnosis after borrowing a book on the subject from my unconventional group therapist. (Unconventional may be a misnomer; he later ran off with a beautiful young woman who was another patient in my therapy group.)

Hypnotizing, Prescribing, and Believing

The first thing the hypnosis book explained was that, for hypnosis to work, I had to act like I believed it would. If a would-be hypnotist appears to have doubts, it becomes unlikely that a real trance can be induced.

In Human, All Too Human, Friedrich Nietzsche noted the functional distinction between great deceivers who believe in themselves, and the founders of religions who in addition truly believe their religious delusions:

“The founders of religions are distinguished from these great deceivers by the fact that they never emerge from this state of self-deception … Self-deception has to exist if a grand effect is to be produced. For men believe in the truth of that which is plainly strongly believed.”

Note that a somewhat grand effect may be something that indoctrination in the psychopharmacology mindset created by psychiatric training enables most psychiatrists to produce; no conscious deception is necessary. (I explore the power of suggestion and the relationship between individuals and authorities in greater detail in The Book of War: The Evolutionary Biology of Racism, Religious Hatred, Nationalism, Terrorism, and Genocide.)

Yet, even if you are a talented hypnotist with supreme confidence, there are people for whom a deep hypnotic trance is unattainable. In my experience, it ran in thirds. For one third, there was no clear effect. One third reported feeling something clearly different from normal waking consciousness, but it wasn’t particularly impressive and was hard to distinguish from a willingness to go along with what was expected. One third, however, readily went into the kind of trance you see when stage hypnotists perform.

A major part of a hypnosis stage show is being able to select out those highly susceptible subjects. I was never particularly good at that part so I always knew my attempt to hypnotize might not work. But as the instruction book made clear, if you let the subject know you have doubts, you will fail. So, step one is to act like you believe it will work even though you know it may not. That I was able to do. Then in my social crowd, once I demonstrated hypnosis with one person, it became easier to act convincingly and get others to go into a trance. Raised expectations made me more effective.

The second thing I needed to learn in order to hypnotize was a technique for inducing a trance. Having the subject stare at an object swinging back and forth worked. As does having subjects close their eyes and telling them to concentrate on their breathing. My go-to technique, however, was having subjects close their eyes (on odd numbers) and open them (on even numbers) as I slowly counted. Every few numbers, while their eyes were closed, I would repeat the refrain about how, “You are getting sleepy. It is becoming more and more difficult for you to open your eyes.” For about a third of the subjects, by the time I got to twenty, their eyelids would start to quiver noticeably as they struggled to open their eyes on the even numbers, and I knew they would soon go into a clear hypnotic trance. Others would go into a less dramatic but significantly strange, sleepy state by the time I got to fifty. Beyond that, it was wise to call it off as I probably had a subject I couldn’t hypnotize.

Shortly after the more susceptible subjects started to struggle to open their eyes, I would tell them to leave them closed and I would continue to count while droning on about how they were “going into a deeper and deeper sleep.” Once they appeared to be in a deep trance, I would experiment with what can be done with hypnosis.

The Remarkable Extent of the Power of Suggestion

My first subjects were my cousins. I told one he would feel no pain when I stuck a needle in his arm. I only stuck it in a quarter of an inch, so it wasn’t very painful. But there was no discernable reaction at all! This hypnosis thing seemed to be working. I was quite amazed. My other cousin went into what appeared to be a deep trance and I had him open his eyes and took him on a hypnotic journey to the New York World’s Fair, which we had previously gone to together. With his eyes open he described what he was seeing! I was impressed. But did he really see the World’s Fair? At that early point in my experimentation, I wasn’t convinced.

Later with friends, I tried post hypnotic suggestions, like “You will have no memory of being hypnotized or of the following instruction: Whenever I say the name ‘Freud’ you will freeze and become completely unable to move.” After waking them from their trance, I then made a series of statements that casually included the mention of Sigmund Freud and watched in amazement when they froze, much to their surprise and bewilderment. But it also made me begin to realize I was playing with fire, because when I called out “Freud” to a friend who was running, he fell on his face. He wasn’t hurt, but this stuff was real, and powerful.

One day, in advanced physics class we had a young, substitute teacher, which if you remember what having a substitute teacher was like in high school, meant that there was total chaos. Since we weren’t doing anything, based on the notion that we were in a science class, I got the teacher to allow me to do a “scientific demonstration” of hypnosis. I needed a volunteer and Bruce, a friend in the class who was at that time en route to Yale (he was no dummy), skeptically offered himself.

Things were going according to plan. Bruce, who had seen me demonstrate hypnosis with our mutual friends, seemed to go into a trance with reasonable ease. I had him stand up and told him he was a monkey. From within his trance he said, “Danny, no!” and visibly started to tremble. Seeing his struggle, I knew he was in fairly deep, so I forcefully repeated, “Bruce, you are a monkey.” Then something remarkable began to happen. Bruce began to curve his arms inward in half circles at his side and make monkey noises, while simultaneously continuing to tremble as if he were trying to resist.

Realizing that he might snap out of it at any moment, I told him to relax, that he was no longer a monkey, and that he was just normal Bruce. I then woke him up slowly with the posthypnotic suggestion that, other than having participated in the demonstration, he would not remember anything that happened. I further suggested that he would awaken refreshed and energized, which he did.

The next day, in the middle of the between classes traffic on a stairway, commenting on our physics class experiment, Bruce told me, “You know you could never get me to do one of those animals …” Then he stopped. Right there on the busy stairway, he fell back against the wall as people continued to rush by, and he turned beet red! The dramatic blushing convinced me that the posthypnotic amnesia was real and had been broken. Like the phenomenon of repression that is the basis for Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, people really can have no conscious awareness of things that simultaneously are retained somewhere in their nervous system. Amazing.

The last time I hypnotized someone was another high school friend who wanted to try it. He was a good subject and I told him I could take him wherever he wanted to go. He wanted to see his dead father whom he had tragically lost a year earlier. And he did. The problem was that after a while, when I tried to wake him up, he didn’t want to leave. I would have panicked if I hadn’t read in my hypnosis manual that, if left on their own, subjects naturally wake up as if from ordinary sleep. But that was too much for me; taking a friend to see his dead father and having him want to stay there made it clear: I really was playing with fire. That was the last time I hypnotized anyone.

The uncanny extent of the power of suggestion was further confirmed by a film I saw of an eye operation—in which a scalpel was taken to a naked eyeball—using only hypnosis without anesthesia! Even though such hypnotic anesthesia could only work for some highly susceptible individuals, if one third of antidepressant users are quite suggestible and another third are somewhat susceptible, that would be more than enough for the power of suggestion alone to account for all the apparent benefit. The placebo effect has been shown to be quite powerful in responding to psychiatric disorders.

Psychoactive Placebos

Note that the antidepressants have side effects that are sometimes powerful and can be quite dangerous. While the more typical side effects are mild, they tend to be quite noticeable. Thus, in many cases, the advantage that the drugs produced could be due to the fact that they simply functioned as psychoactive placebos, i.e., placebos that produced enough impact on the subjects’ experience to make it seem certain that they were taking a real medication and were not in the placebo arm of the research. For example, a sizeable dose of niacin (vitamin B3) produces a sensation of a hot, flushed red face without having any specific psychological effect. A psychoactive placebo produces enough change in subjective experience that the subject becomes convinced that they are taking a real drug and are not taking a placebo. This would obviously enhance the power of suggestion.

Antidepressants may have some benefit beyond the placebo effect for some individuals, even though as yet we have no clear unequivocal evidence that they are more effective than a psychoactive placebo. Whether antidepressants are more effective than psychoactive placebos has not been demonstrated by studies financed by pharmaceutical companies as they utilize inactive placebos; the evidence we do have is thus consistent with antidepressants being psychoactive placebos (see “The Psychiatrist’s Dilemma: In Defense of Placebo Psychiatry” on Mad in America).

The Power of Suggestion and the Problem Posed by the Effectiveness of Placebos

Based on recent numbers, over 42 million Americans age 12 and over are taking antidepressants. We know that 85% of these are getting no benefit over the placebo effect; if psychoactively enhanced placebos had been used in the studies, that number might very well approach 100%. That means that we can be sure that at least 35 million people age 12 and over (85% of 42 million) are being exposed to the side effects of antidepressants (including a large increase in suicidal ideation and suicide) with no demonstrable benefit.

Can this be justified?

Dan, thanks for this great article! If you haven’t seen it yet, check this out and prepare to have your mind blown: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00048674231218623.

Report comment

I lost control of a barking dog called ‘me’: it ran away and jumped into the sea. Then a mermaid came to rescue ‘me’, and brought ‘me’ back and married ‘me’ in me. Who am I? I think the sea.

Report comment

The brain needs urgently to complete it’s evolution now people, so please, understand this. The evolution is completed through observing the processes of thought and feeling and the life activity as it is, in freedom, and through that observation, the brain begins to understand IT’S OWN operations. Now, how can the brain operate efficiently or understand anything if it cannot understand it’s own operations? And can you see that through simply observing it’s own operations without justification or condemnation, in freedom and without interpretation, it is changing itself to reflect the perceptions it has grasped and becoming more efficient in it’s operations and it’s functioning? This transforms the brain including the left brain and it’s thinking, so you can put all your intellectual activity to one side. The intellect is best transformed and perfected through silent perception of what is, and most importantly of all, it’s own thinking, feeling and acting, and then you will have paint stripping eyes and understand all people – as yourself, but that latter comment would need explaining and I have no time. It dissolves through perception you see, it being both time and yourself which is mere thought. The self is mere thought – time is mere thought. Time does not exist – clocks exist. Thought is time and time is thought. The self is thought and there is no self when you are amazed by an incredible, unexpected scene of nature like a dark blue sky filled with stars and a passing comet shooting past, and there is no self at all when you are enraptured by a perfect symphony or watched your team perfom the perfect winning goal, and there is no self or thought when you’re enraptured in the most perfect and free sex you ever had. And these are memorable experiences, so you are obviously not this self. In France they call an orgasm “petti morte”, or little death (spelt dyslexically I’m afraid). let’s go for the big death instead! It’s much more fun. It’s called living with what is, seeing not thinking.

Report comment

Built a world of glass. It’s a shattering image. Death capped worldviews, the usual reserve. A world as clean as our workwear, which was stitched by bony fingers, wage enslaved children with respiration illnesses. With heaving lungs of industry you bow there, straining. And Frau – you amble in my sleep: in my healthy box of disabled malice. The teeth of your chainsaw are the stars.

Report comment

This was a long but interesting dive into the power of suggestion.

And yet Dr. Kriegman persists in his belief that human experience is somehow stored in the nervous system.

Many researchers, including my teacher in the “early days,” have used hypnotism as a therapeutic tool. It has been used successfully for this purpose. But as Dr. Kriegman’s experiments also demonstrated, the power of the post hypnotic suggestion is very real.

My teacher used this finding to create a therapy that aimed to dig out and “discharge” suppressed commands or experiences that functioned as post hypnotic suggestions even if that was not their original intention. And in this process (which did not use hypnosis, but could be considered a process of “waking up” a being) he discovered past life incidents and had to reconstruct his original ideas about human personality and human memory.

But can you imagine if one could create a machine that would hypnotize people and “automatically” install post-hypnotic suggestions of a serious nature, then release them back into society, never suspecting that they had undergone this treatment?

This is the world we live in today. We have a population operating on “suggestions” that occurred accidentally while they were in some pain or drug-induced trance. And most of us also carry suggestions that were purposely installed in us, also without our knowledge. This results in a sort of psychological prison, where the walls are composed of nothing more than commands installed while in a trance. Our willingness to detain each other in real prisons only complicates the situation.

Dr. Kriegman’s essay gives us clues about a real way out of this mess. I wish it had gone farther.

Report comment

Heart- and soul-felt thanks for a most magnificent essay.

I suggest that few phenomena better illustrate the suggestibility of us modern humans than our falling for the suggestion that “‘depression’ causes hopelessness.”

“Depression,” I suggest, IS hopelessness.

“Oh, what idiots we all have been. This is just as it must be.” – Niels Bohr,

from

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Niels_Bohr#:~:text=It%20is%20a%20great%20pity,cannot%20possibly%20have%20understood%20it.

My wife, whom I constantly accuse of being a faith healer, constantly suggests that she is not, and that I am merely “very suggestible,” a suggestion I find seductive but which I completely reject, partly as I fear doing otherwise might imperil her faith healing powers over me. (Some time ago, she announced over breakfast, “You know what your problem is?” “No,” I announced. “You’re, em……..pathetic,” she announced. And maybe I am, too? But, when I ask folk, who unwisely ask me how I am, what they think it must be like to have to live with somebody who has to live with somebody like me, I get little empathy, sympathy or even pity.)

“[‘]Of course not … but I am told it works even if you don’t believe in it.[‘ – Niels Bohr.]

Reply to a visitor to his home in Tisvilde who asked him if he really believed a horseshoe above his door brought him luck, as quoted in Inward Bound : Of Matter and Forces in the Physical World (1986) by Abraham Pais, p. 210.”

from

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Niels_Bohr#:~:text=It%20is%20a%20great%20pity,cannot%20possibly%20have%20understood%20it.

Folks very reasonably argue that psychoactive/psychotropic drugs interfere with whatever the diagnosed neurosis/psychosis may actually be trying to teach us, as emoting creatures, and that those undergoing “psychotic breaks” or “psychotic fixes” or spiritual emergencies or acute and turbulent spiritual awakenings may find themselves suspended in nasty, in-between states a bit like anyone left departiculated in a “Beam-me-up, Scottie” teleportation machine.

I dare to suggest that it is the one and same wildly intelligent, savvy AND loving cosmos (even if she has any number of parallel universes within her) who births us that also serves us up all our emotional traumas, ACE’s etc. et cetera, and also that very self-same one who has thus far visited all sorts of utterly inappropriately prescribed psychotropics on hapless victims to add to their individual, unique challenges with at least infinitely exquisite discernment…and that, by nowadays gifting us with access to such minds and works as Dan’s and MIA’s, Nature/Life/Evolution/Our Cosmos and Her Creatrix and now, finally, allowing us to see the light – the light of Hope.

However one views hopelessness, its sure cure can hardly be other than be the permanent restoration of permanent hope – can it?

And, as usual, I suggest, Eckhart Tolle is right in suggesting that we try to accept each moment as though we had chosen it….and, when when find ourselves unable to do this, to try and accept our non-acceptance, as well as suggesting that:

“Life will give you whatever experience is most helpful for the evolution of your consciousness. How do you know this is the experience you need? Because this is the experience you are having at the moment.”

― Eckhart Tolle, “A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose.”

I believe another guy tried to explain all this to us a couple of millennia ago, but was widely misunderstood – until now – with his suggestions that we repent, undergo a transformation of consciousness to Consciousness, wake up and realize that we all ARE “the I-AM,” the eternal “Light of the World,” the “Before Abraham was, I-AM,” the “Before you were in your mother’s womb, I knew you,” the “I am that I am,” and that Zen, the realm of formless, unmanifested Consciousness, a.k.a., the Kingdom of the Skies, of the Heavens, of Heaven, of God, of “the Father” is within us all, as in all things and outside all things, and so to give us eternal hope, as well as reportedly making generous use of suggestibility, of suggesting that one’s “sins” are “fore-given” one, of getting at the root of shame, of the placebo effect, and occasionally, of placebos, too. I think that guy thought he came to sow peace until realizing and acknowledging, towards the end, that, er, oops, maybe not so, or not so fast, or maybe not for a couple of millennia, anyway:

Gnostic Gospel of Thomas:

“(16) Jesus said: Perhaps men think that I am come to cast peace upon the world; and they do not know that I am come to cast dissensions upon the earth, fire, sword, war. For there will be five who are in a house; three shall be against two and two against three, the father against the son and the son against the father, and they shall stand as solitaries.”

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household” (Matthew 10:34-36).

Thanks, again, Dan and MIA, for a most extraordinarily fine essay!

Tom.

“Since I gave up hope, I feel so much better.”

Report comment