“We enrolled you in Pacific Life Program because we LOVE you too much not to!” -My mother, first letter from home

People often ask me if I hate my parents for sending me away to a troubled teen industry program. The troubled teen industry (TTI) is a network of therapeutic boarding schools, wilderness camps, and religious reform programs that claim to treat mental health struggles in teens. In the past few years, these programs have been under scrutiny for reports of abuse, manipulation, and even causing deaths among students. I spent 14 months in one of these programs, where I was isolated, medicated without informed consent, and subjected to emotional torment.

The TTI uses psychological persuasion tactics to capitalize on the guilt parents feel when their children face mental health challenges. They weaponize the label “troubled” and ingrain fear into parents, pressuring them to buy into their programs. Falling for the TTI’s manipulation leads to harmful consequences not only for the child but also for their parents.

While we live in an era where awareness of mental health is becoming more widespread, the reality for many families seeking help is that they feel lost while navigating the mental health system. Being a teen struggling with depressive episodes, I found myself thrown into this system, but it was more focused on labeling me as “troubled” rather than providing me with the support I needed. When parents, like my own, hear this term, they are led to believe they are failing. This idea that they should be able to “fix” their child leads to overwhelming distress over the constant struggle to meet unrealistic expectations.

Research confirms the emotional toll it takes on parents when caring for children diagnosed with serious mental illness. Parents confess that they feel constrained by feelings of inadequacy and the weight of societal stigma. They feel trapped in their circumstances, believing that they aren’t capable of guiding their children themselves and that conventional support systems are failing them. Insurance wouldn’t cover the care I needed, leaving my parents scrambling for something within their budget. The stakes felt incredibly high, and in this vulnerable moment, the TTI stepped in, offering false hope to the hopeless.

Studies also show that the quality of life for these parents is negatively impacted, often leading them to seek drastic solutions. The TTI uses this to convince parents that necessary “tough love” interventions, including sending their child away to one of their specialized programs, are the only solution. My parents genuinely believed they were making a loving choice. The program insisted that “troubled” teens, like me, can only get better if we are taken out of our everyday life and forced to earn it back. They claimed that this would cure my depression, as if it stemmed from entitlement rather than pain. Our freedom was no longer a right, it was a privilege.

The label “troubled” is a harmful stereotype that portrays teens as inherently problematic. The TTI frames depressive behaviors in a disrespectful manner, framing the teen’s existence as an issue in need of fixing. Research indicates that societal perceptions of mental illness can depict adolescents as uncontrollable. A study highlighted that children diagnosed with mental health conditions, such as ADHD and depression, are often viewed as potentially violent, leading to increased support for involuntary treatment. It isn’t uncommon for these ideas to fuel a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Adding to this, over 47.2% of a surveyed population in Southern California reported that they associate mental illness with dangerousness, mainly linking conditions like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder to violent behavior. As my depressive episodes continued, families became wary of me, thinking I could potentially influence their kids. Almost as if I were contagious. Due to this, I struggled to find the good within myself, leading me to lean into self-destructive habits. The results of this social stigma fuel the TTI’s marketing strategies as they claim they will save us from ourselves. My program turned us into villains, overlooking that many of us were victims long before our stay.

The troubled teen industry relies on manipulative tactics that are similar to cults, which makes sense given its ties to the cult Synanon. TTI programs prey on scared parents by using coercive methods to persuade them into buying into their costly and often abusive programs. The cognitive dissonance parents experience is powerful: they are being told they’re not doing enough to help their child, even when they are desperately trying. Like many of my peers, I had been in therapy prior to my time in the TTI, but I had not yet received a proper diagnosis. My parents were worried about why I wasn’t getting “better.” This made selling behavioral correction easy because it offered a false resolution. Finally, my parents had something that could free them from their self-doubt. By targeting anxious parents, the TTI’s manipulation tactics push them to make decisions they might not have considered otherwise.

Deception is a deeply entrenched part of how the TTI operates. One of the primary strategies is the creation of perceived authority; parents are frequently referred to TTI facilities by “educational consultants” who present themselves as trusted experts. These consultants are financially compensated for each enrollment, which raises concerns about a lack of transparency. The consultant who convinced my parents to send me away occasionally gave them updates about how well I was supposedly doing. I never had a single conversation with this man. My parents’ interactions with him were limited and mainly focused on securing and maintaining my enrollment.

The TTI also creates a sense of urgency through manufactured scarcity, using phrases like “Act now before it’s too late” to scare parents into taking immediate action. This fear-mongering bypasses rational thought, preying on emotional responses. TTI programs rely heavily on social proof to reinforce their messaging, especially through word of mouth and carefully selected testimonials. Other parents told mine not to believe me if I said anything negative about the program. They said resistance was part of the process, and that once I gave in and worked the program, I would be “fixed.” These narratives are misleading.

These programs, though marketed as “therapeutic,” are nothing more than profit-driven enterprises that exploit families at their most desperate. This exploitation is more than just a financial burden. Survivors repeatedly describe feelings of being abandoned, betrayed, and manipulated by both the TTI programs and, in many cases, their parents. I’ve always found myself more upset with the program for manipulating my parents, but I couldn’t help feeling frustrated by how long it took them to finally believe me. It’s hard for parents to accept that they were deceived into paying for their child’s abuse. It doesn’t help that the TTI isolates parents from their children’s experiences, claiming that our confessions of abuse are merely manipulation tactics.

The coercive control kids experience within TTI programs impacts their ability to trust authority figures, build healthy relationships, and navigate social interactions, leading to self-esteem challenges in adulthood. Within the first 24 hours, I was sent to solitary confinement for asking questions I didn’t know were off-limits. That was how I was first introduced to the program. They ripped my teenagehood from me. While my friends were getting their licenses, first jobs, and going to prom, I spent my sweet sixteen being scolded for being “manipulative.” I just wanted a slice of my birthday cake like the other girls, but the diet they forced upon me made that a privilege I wasn’t awarded.

In a journal entry, I wrote: “I don’t understand why they won’t let me go home. I’m working the program like they want me to.” Many survivors feel like their basic human rights were violated within the TTI, leaving us with the pain of being abused by a system that was supposed to protect us. Being sent away isn’t a matter of short-term discomfort but a fundamental breach of trust.

Thankfully, Pacific Life Program is no longer running as medical malpractice ran rampant. By lying about the side effects, they manipulated me into consenting to a medication called Epival, a “mood stabilizer.” When I started to express distress over the rapid weight gain caused by the medication, they blamed me and put me on a strict diet. While other girls complained of still being hungry, I was given 75% of the girls’ meal portion, which was already significantly smaller than the boys’. When I felt lightheaded, often from not eating enough, they accused me of faking it to manipulate them. Like many teenage girls, I developed disordered eating.

According to a study that surveyed 1,739 adolescent girls between the ages of 12-18, they found that 27% of them struggled with distorted eating habits. But the researchers relied on self-reported questionnaires, which makes me question… how many of those surveyed girls fell into the common “social desirability response bias” trope? How many of those girls are still suffering in silence? I know I suffered in silence for many years post-program.

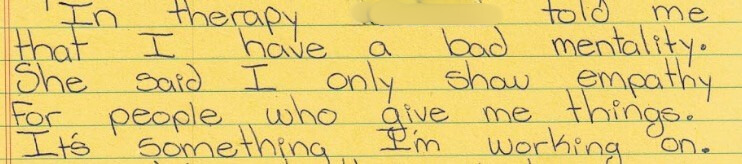

But it wasn’t just the restrictions and forced silence; it was the emotional abuse disguised as therapy. They told me I was a fundamentally bad person, that I manipulate people into being my friends, and that it was only a matter of time before everyone figured it out. Eventually, I started to believe them. In a letter I sent home, I wrote, “In therapy, [redacted] told me that I have a bad mentality. She said I only show empathy for people who give me things. It’s something I’m working on.”

This still lingers within me, almost as if a staff member is stuck in my head, reinforcing the shame. Shame is a powerful control tool, especially during such a formative part of life. Research says being shamed during adolescence can become ingrained in someone’s self-identity, making them withdrawn, socially inept, and unsure of their true self. When kids come home after being in the TTI, parents tend to perceive the change in their behavior as positive. They don’t understand that we have been shamed into compliance. My time in the TTI was more than an attack on my bodily autonomy; it was an attack on my personhood.

The troubled teen industry does not just harm teens; it pulls families apart. Though it’s been over five years, I still find myself learning how to cope after my experience. Meanwhile, my parents struggle to accept that they were misled into believing they were doing what was best for me. This cycle of misunderstanding cannot be broken until we address the core of this issue: the label “troubled.” This pervasive term lacks empathy for struggling teens. We must rethink this label as parents’ distress often mirrors their child’s. Parents are not the enemy here. They, too, are victims of an industry that exploits their pain. The solution isn’t fixing this so-called “trouble”… it’s dismantling the system that profits from it.

So no, I don’t hate my parents. I know they were troubled, too.

Way to go!!

Report comment

Emma … I found your piece to be thoughtful, enlightening and also quite moving. Would very much like to know your thoughts on what sort of treatment might actually have helped you, and others like you, get through those “troubled teen” years.

Report comment

Thank you so much for reading!

Maia Szalavitz, who wrote the book “Help at Any Cost,” has done an incredible job offering compassionate alternatives. I’m a big fan of her work. She advocates for things like outpatient therapy (with licensed mental health professionals), family-based approaches like Functional Family Therapy or Multisystemic Therapy, and harm reduction strategies for teens struggling with substance use. She also stresses that residential treatment should only be used as a last resort, in cases of immediate danger.

Thank you again for asking this question.

Report comment