For nearly two decades, I have suffered from a debilitating condition known as PSSD, short for “post-SSRI sexual dysfunction”. Contrary to what the name suggests, the condition often encompasses a much broader constellation of symptoms than simply sexual difficulties, such as cognitive deficits, emotional blunting, and anhedonia which can severely impact a person’s functioning and quality of life. My journey with this condition led me down a path where I ended up engaging with community efforts to investigate it, to try to spread awareness, and to elucidate aspects that I believe urgently need research so patients can access the correct diagnosis and potential access to treatments.

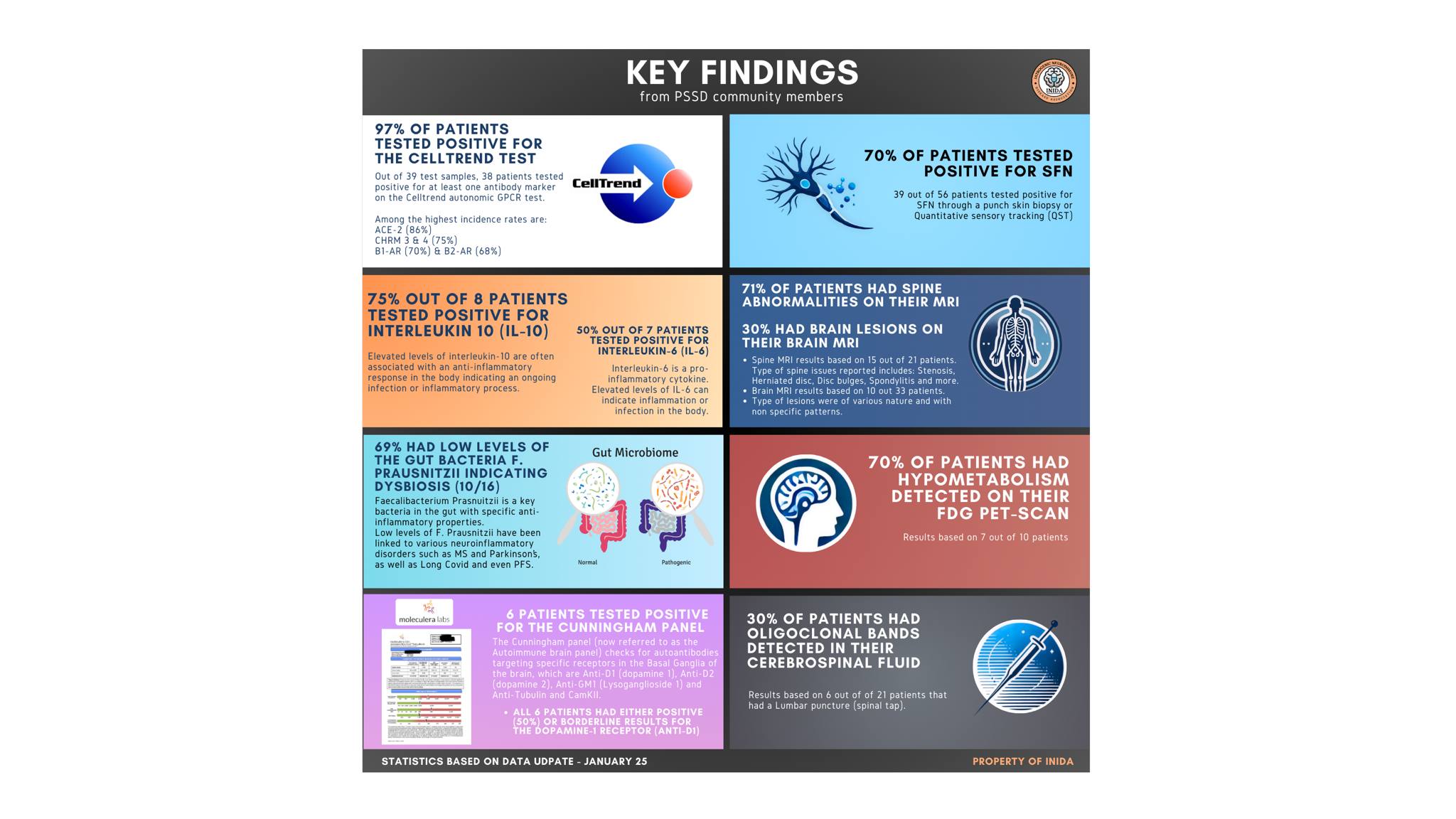

The search for answers ultimately led to a two-year-long collaborative research effort, investigating PSSD by collecting and interpreting test result from over 100 PSSD patients in the community, including autoantibody panels, skin biopsies, neuroimaging, lumbar punctures and more.

This effort eventually culminated into the creation of a research document, suggesting that neuroimmune processes and related downstream mechanisms may play a role in PSSD.

Our data shows that 70% of 56 patients tested positive for small fiber neuropathy (SFN), a type of nerve damage often seen in autoimmune conditions.

Additionally, 97% of patients were positive for at least one biomarker on the CellTrend GPCR autoantibody panel. Furthermore, high incidence rates were seen in several biomarkers, such as ACE-2 (86%), cholinergic-muscarinic receptors 3 and 4 (75%), as well as Beta-1 (70%) and Beta-2-adrenergic receptors (68%).

The results indicate that autoantibodies may be targeting the autonomic nervous system, causing dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction), which has been reported by many PSSD patients.

The current version of the document showcasing all of these findings and our discussion of their implications can be found here.

Loss

For nearly two decades, not a single day has gone by without having had a suicidal thought. I’ve felt like a chemically lobotomized zombie, forced to witness life pass me by, unable to really experience or participate in any meaningful way. I’ve been stripped of everything that made me a functioning human—everything that made me—ME. I could write a whole book about my story, but I’ll try to keep it brief to focus on what led me here and the way forward.

At age 14, after the passing of my grandfather, a big character in our family, I was prescribed the antidepressant Zoloft (sertraline), indicated for OCD, an issue I had increasingly dealt with for the previous couple of years. Therapy hadn’t worked and the pills were sold to me as safe and effective—“the next big thing”. Contrary to what I was told however, not only did they not help, they also took away something essential from me, the very essence of what made me human—my ability to feel emotions. It wasn’t clear at first, but slowly crept up on me.

I remember straight from the get-go that the pills made me feel agitated, restless and paranoid. I didn’t know at the time what was happening and assumed these “side effects” would pass. I couldn’t function at school; I became a nervous wreck. I ended up weaning off fairly quickly, and while some of the side-effects passed, I still kept feeling off. I also started getting partially numb down there. Something was wrong. I was told the side effects would pass; I chose to believe the doctor.

Later that year, just at the start of 10th grade (about half a year after my grandfather died), my dad abruptly passed away.

This is the first time I remember feeling like something was really off. I couldn’t properly react to it; I couldn’t feel it. I just couldn’t respond to it. I could force some tears but I had a really hard time connecting to what had happened. It felt like some sort of dream; I felt completely detached from it. It didn’t make sense to me. My dad had meant so much to me, and I had always been a sensitive kid, so why couldn’t I feel it?

I eventually connected the dots, but at the time, I was still so new to all of this—I grew up thinking that the doctors knew best, and that they wouldn’t offer something that wasn’t safe. But turns out Zoloft didn’t only take away my ability to feel emotions, it essentially took away my ability to grieve and process my dad’s passing. And the crazy thing is, I still feel like it’s unprocessed even to this day. In many ways I feel like time has been frozen ever since this happened.

Despite feeling numb, my reaction to my parent’s passing came out in other ways—my OCD and depression got considerably worse, and after months of failed therapy I was put on Zoloft again. I became more blunted, and started feeling more numb and non functional down there. I also felt l detached socially. Despite reassurances that these “side effects” would pass once I stopped the medication, they never did.

After a year, I tapered off but I was still the same. I had all these new issues now that I never had prior to using the drug: emotional blunting and sexual difficulties, at the age of just 15. There was nowhere to turn for help; the internet didn’t have much info on it at the time, besides a few scattered anecdotes on some forums, but nothing concrete. I was really worried that this wasn’t gonna go away, but I was too ashamed to bring it up to anyone. Eventually I did speak to a couple of doctors; both said it couldn’t happen.

As years went by, nothing changed. I was still functional to an extent—I could get my junk up but it wasn’t as strong as before and the sensation was dulled and orgasms were weak. In some ways, my condition was kind of mild at the time compared to what was to come.

The Final Nail

Three years after stopping Zoloft, at age 18, I was offered Lexapro due to a severe depressive episode. While I was hesitant, I accepted it because I was struggling so much. I thought, “Hell it can’t get any worse right?” How wrong I was.

I remember the pills making me more social at first, but also agitated and restless. I got increased sexual dysfunction which was expected as a side effect—more genital numbing and decreased orgasmic sensation. I hoped, however, it wouldn’t get worse than before. I still hoped the doctors were right—even if it doesn’t make sense in hindsight.

After three months, my depression was milder (due to better life circumstances), so I thought at the time, “I’m ok, I don’t need this anymore,” and I turned to my GP to ask if I could stop the drug abruptly. While he advised me that it would be ideal to taper, he said that at worst, I would just experience increased withdrawal symptoms such as brain zaps for a period of time. I thought, “Hell I can deal with a few zaps,” and so I decided to go off cold turkey. I just wanted to get it over with. And as predicted by my doctor, the brain zaps came, but so did other things too.

After stopping the drug, I started experiencing increased symptoms of sexual dysfunction. Suddenly I couldn’t get it up anymore. I also got severe genital numbness and anorgasmia—I could barely feel anything down there. I started freaking out. I knew it was the drug; there was no question about it this time. Once again, a pharmaceutical had altered an essential part of my body.

Over the following weeks and months it only got worse.

I developed severe anhedonia—the inability to experience pleasure, probably one of the worst aspects of this shit disease in my personal opinion. I just couldn’t find enjoyment in anything anymore. No matter what I tried, nothing gave me anything. I ended up spending a lot of my time just apathetically staring at the ceiling. I couldn’t feel music, watching movies I had always loved was like watching gray paint dry, and I stopped sensing the atmosphere in my environments. Everything felt the same. I got insomnia and could barely sleep. My body felt weak, like I had lost muscle strength. I also developed severe cognitive issues, impairing my ability to comprehend, memorize and think clearly. My creativity vanished, the one thing I held sacred that in many ways had defined who I was. I didn’t feel human anymore. I felt like a robot.

Once again, I turned to the internet for answers, and while information was still scarce, this time around there were some community forums and such dedicated to the topic. While I did find some solace in the fact that I wasn’t alone, I also felt increasingly hopeless over the lack of recovery anecdotes, and came to the realization that most people didn’t seem to recover from this. Outside of a couple of natural recoveries, some people improving to some extent over time, and some reporting transient relief from certain substances, most people were reporting the same symptoms as me and were desperately looking for relief—but PSSD was here to stay.

After eight months, I got some minor cognitive improvements. The rest stayed pretty much the same, and approximately a year after I quit the pills, chronic fatigue set in—the final “gift” from Lexapro. I was now a 19-year-old, ready to “take on the world”—with debilitating symptoms of sexual dysfunction, cognitive deficits, anhedonia and chronic fatigue. I was supposed to be living the best years of my life, but instead I ended up locked up in my apartment and fell out of studies after just two months.

There was no relief. Not even alcohol had any effect—I could down almost a liter of vodka but only my body would get wobbly and dizzy; besides that I felt nothing. It was bizarre. I tried so many times to go out to party with my friends, but I just felt extremely depressed as I watched everyone around me have fun and connect with each other, while I was stuck in this cold, hopeless void, with a brain that felt like it was wrapped in a chemical straightjacket. Dating was more or less impossible. My inability to connect emotionally and function sexually turned away any potential partner.

A year and a half after quitting Lexapro, nothing had changed. Around this time I asked my doctor for a referral to a neurologist, but they declined as this was “psychological” in their view. Instead I was offered more pills and talk therapy. I ended up housebound for the next four years.

Trapped

The lack of help from the medical field and the lack of knowledge online sent me down a decade-long path of “research” and self-experimentation. Countless supplements and over 30 different pharmaceuticals, I pretty much tried it all. I knew PSSD was here to stay, so I felt like I had nothing to lose. It was either that or I could be a housebound wreck, waiting forever for research and treatment options to catch up, which didn’t seem likely at the time.

While I did experience transient relief in certain symptoms from some of my trials, others made me worse. It was like Russian roulette—just as it had been with the SSRIs. I did eventually discover some tools that gave me enough of a boost for short periods, which I used to buy time, functioning just enough in periods to try studying and a bit of work while I waited for future treatments and hoped for natural recovery.

Over the years, most of my symptoms stayed the same, while some got worse. I did, however, experience minor fluctuations, as well as a few bigger so-called ”windows” where my symptoms would decrease drastically, which was confusing, but also showed me my body and brain could still work to some capacity, which gave me some semblance of hope to keep going.

Perhaps I wasn’t totally broken; perhaps this wasn’t irreversible damage, but rather some form of alteration in function. But without knowing what PSSD was and how to treat it, all I could do was wait as my symptoms persisted, and the windows got fewer and far between.

As the years passed, I remained trapped in this “chemical straightjacket” with a body and mind that no longer functioned as it was supposed to. After a decade of failed treatments and declining health, trying desperately to keep pushing forwards with studies and work, I just couldn’t do it anymore, and was forced to go on disability.

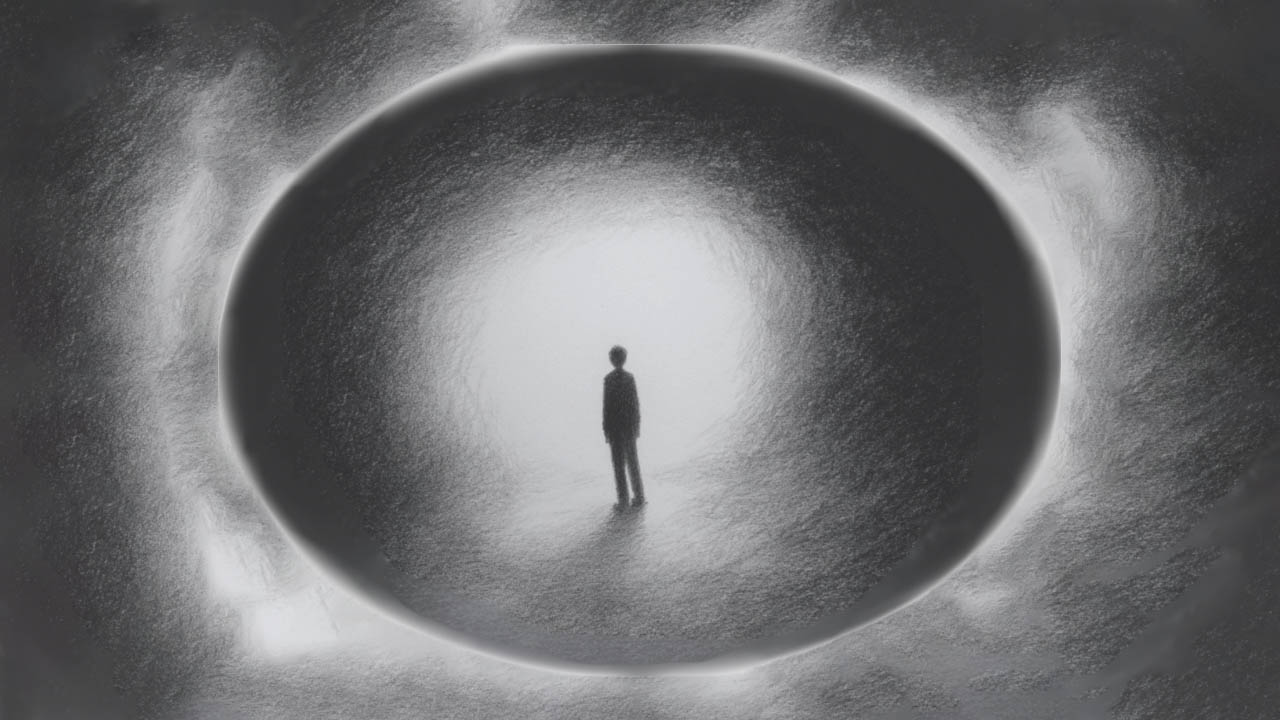

The grief of what I have lost and missed out on is immeasurable. I slowly came to accept that my life is essentially over, at least the life I had always envisioned. Now, every day feels the same. I can’t even enjoy the simplest of things like watching TV or a cup of coffee. I can’t feel hunger, my sleep is never refreshing, and I feel like I’m in a constant fog, unable to think clearly. I can’t connect emotionally to other people and I can’t function properly sexually.

Many days are spent catatonically staring at the ceiling, without any thought or drive to do anything. Meanwhile I’m constantly reminded of what I’ve missed out on, watching people around me evolving, experiencing and achieving the things I couldn’t. I sometimes tell people it feels like I’m stuck in this horrible “sandwich” of torment, where I battle the symptoms every waking moment, parallel to grieving over the past and ruminating hopelessly about the future. It feels like I’m stuck in some kind of purgatory—it’s as if time has stood still ever since I took those pills almost 20 years ago.

The “Side Effects” of PSSD

It’s hard to fully describe what it’s really like to have PSSD and what the consequences of that can be. I wish to try to showcase this by using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as an analogy, as I think it provides a powerful framework for illustrating the breadth of areas affected by PSSD. This is a widely recognized model of human motivation that highlights how unmet basic and psychological needs prevent self-fulfillment.

For a majority of patients suffering from PSSD, many, if not all, levels of Maslow’s pyramid can be unattainable.

Even the most basic needs may go unmet. Hunger and appetite may vanish, while sleep disturbances like insomnia or unrefreshing sleep becomes the norm.

Sexual desire, pleasure, and physical function are often lost entirely, halting patients from seeking out their most basic biological need.

Extreme fatigue can make basic activities like dressing or even maintaining hygiene feel insurmountable, and physical health can often deteriorate due to an inability to exercise. Cognitive impairments may disrupt the ability to work or study, leaving patients vulnerable to job loss, academic failure, bullying, and financial insecurity. Many are forced to rely on disability benefits or family support.

Emotional blunting and anhedonia further isolate patients, making it difficult to connect with loved ones or build any meaningful relationships. Those who still try, may experience ostracizing by their peers. Those with spouses or children often face profound guilt over losing their emotional connection, which sometimes can lead to marital breakdowns or estrangement from family members.

Without the ability to participate in society, patients are deprived of the respect and self-esteem necessary for a sense of worth, often feeling like burdens to others. This can lead to patients completely isolating themselves from the world, as their inability to function and participate in daily life leads to a vicious cycle of depression, anxiety, and loneliness, perpetuating their suffering.

Dreams of building a family, pursuing a meaningful career, or achieving life goals fade, as the motivational drive and ability to strive toward such aspirations is extinguished. Even when patients muster the strength to seek help from medical professionals, they are more often than not dismissed, invalidated, and not offered the help that they so desperately need.

PSSD patients frequently describe a profound sense of loss—of self, identity, who they once were, and the future they once envisioned. For many, life becomes a mere existence, stripped of fulfillment, connection, or purpose. In some instances, the relentless torment and suffering from PSSD may drive patients to commit suicide.

Suicide is unfortunately quite common in these spaces. I’ve often struggled with such thoughts myself—and I’ve seen them take many others. Just this past year alone, at least seven people in the community took their own lives.

Coming to terms with this reality forces you to see the world differently.

The deeper I fell into this condition the more I began to question everything I once took for granted—about medicine, mental health, and the systems we trust to protect us.

I often compare my experience to The Matrix—where the protagonist, Neo, is offered two choices by a mysterious man: a blue pill that will keep him in the simulation, unaware of the real world, and a red pill that will wake him up from the simulation, and show him the truth about the real world.

I essentially took that red pill, which revealed the truth of a broken, corrupted system. Unlike Neo, however, I never got the chance to know what I was choosing. No one warned me. My consent wasn’t informed, it was essentially manipulated by Big Pharma’s greedy pockets and decades of corruption that has seeped into the entire medical system.

I don’t blame most doctors for not knowing better. The issue runs deeper than individual practitioners—it’s systemic. Most well-meaning professionals simply don’t know. The ones that do are often the ones who have suffered at the hands of the system themselves. This needs to change.

It’s time now for the rest of the world to wake up and smell the ashes.

A Broken System

After nearly two decades of navigating the medical system, I’ve seen it all—ignorance, dismissal, and outright gaslighting. The response to PSSD from many healthcare professionals has very often been an immensely demeaning and negative experience.

- “This sounds like depression.”

- “There is nothing wrong with you. This is likely psychosomatic.”

- “What you’re saying is in your head.”

- “Stop making up diseases.”

- “This sounds like delusional disorder”.

- “Maybe you should just learn to live with it.”

These are some of the things various doctors have said to me over the years. This is also the reality for thousands of patients suffering from PSSD. Many doctors refuse to look deeper, dismiss symptoms outright, and lean on outdated knowledge as if medicine stopped evolving after medical school. Instead of curiosity, we may get arrogance. Instead of investigation, we often get deflection. This isn’t just a case of a few bad doctors—it’s systemic.

Patients often get wrongfully diagnosed with all kinds of conditions, where their file is muddied with inaccurate and stigmatizing information that makes it even harder to be taken seriously by the next one. Many experience being labeled as hypochondriacs, some even as delusional, and this often happens without even being offered a basic physical checkup. Instead, they are handed pills first and asked questions later.

This is the biggest problem I see with psychiatry—it is largely based on outdated models and a lot of pseudoscience.

Many of the conditions in the DSM are so vague that you could easily fit most symptoms within a psychiatric label. And, thus, many doctors choose the easy way out and use the DSM to apply a diagnosis to describe their patient`s symptoms, often without even offering a basic physical checkup to rule out other potential causes. Then they hand you pills that may be harmful and send you out the door. Is this really where we are at?

There are many well-meaning doctors that have been blinded by Big Pharma’s narrative and just don’t know any better. This is what they are taught. The medical field has become complacent, prioritizing pharmaceutical profits, insurance companies’ agendas, and established narratives over patient’s well-being. If something isn’t in a textbook or a part of the standardized narrow system that they operate by— most doctors simply refuse to acknowledge it.

But medicine is supposed to be about discovery. It’s supposed to be about solving problems, not ignoring them. The medical system has largely failed in its duty to offer sufficient help to patients with complex disorders such as PSSD. Big pharma’s corruption has seeped into every aspect of the medical field, corrupting the actual science that the practice should be built on. It’s time to take science back to its roots—where discovery and patient care come first, not corporate interests.

And don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to demonize pharmaceuticals here, as some have their use and many people seem to have found relief in them. I’m simply saying that we have to acknowledge both aspects, listen to the patients and investigate this properly so we can gauge both sides of the coin. We need to figure out why this happens to some individuals, so we can properly screen out future patients that are at risk as well as offer solutions and treatments to current sufferers.

As it stands now, we are largely left to fend for ourselves and take matters into our own hands. Together, though, I believe we have the ability to make a difference.

Finding Meaning in the Search for Answers: Community Research

Despite everything, I’ve found a sense of purpose in investigating PSSD among some of my peers, and recent developments in the community over the past three years have offered some sense of hope that there might be a way to at least improve the symptoms. Focusing on this aspect has kept me occupied and offered some form of meaning in this otherwise difficult experience.

The turning point for me came when a patient, nicknamed “Patient Zero” to protect his identity, made a post on online forums stating that he had been diagnosed with a novel autoimmune condition affecting the central and peripheral nervous system, a part of which included findings in his cerebrospinal fluid as well as a diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy (SFN), confirmed with a punch skin biopsy. He urged other patients to seek out the same testing.

A Finnish Facebook group was formed to track these developments, where several patients turned out to be positive for SFN as well. A few months later a YouTube interview with psychiatrist Josef Witt-Doerring featured a woman discussing immune-mediated SFN and immunomodulatory treatment for PSSD.

Intrigued and inspired, with some form of newfound hope, I sought her out and joined a Discord server she ran, with a focus on autoimmunity and neuropathy. “Goldenhour”, which was her online persona, had gathered a lot of papers and done extensive research into autoimmune conditions and SFN.

As I started familiarizing myself more with the topics, it was made apparent to me that there was already existing literature showing that drugs such as SSRIs had triggered immune-mediated neuropathy in the past. The first commercially available SSRI “Zimelidine”, was taken off the market during the 1980s following numerous reports of patients acquiring Guillain Barrè syndrome (GBS) following the use of the medication. GBS is a serious autoimmune condition that targets peripheral nerves.

This was an eye-opener for me, and further cemented my feeling that we were on the right track.

Inspired by another test Patient Zero had shared online a few months earlier, Goldenhour had created a table for tracking CellTrend results (a GPCR autoantibody panel linked to immune-mediated autonomic dysfunction), which showed a high incidence rate even though the sample size was small at the time.

I offered to help out and eventually became involved in tracking patient test results, expanding the scope to include tracking skin biopsies for SFN by corresponding with members through online platforms such as Discord, Reddit, and Facebook.

Eventually, as Goldenhour’s symptoms had started improving in response to her treatment, she decided to leave Discord to focus on her life, handing the server over to me and another admin, “Arcane”.We continued running the server, gathering data, corresponding with community members and expanding on the research. We started tracking more testing categories while doing deep dives to familiarize ourselves with the topics—Cunningham panels, cytokine panels, lumbar punctures, PET scans, MRIs, and gut microbiome analyses—all of which showed interesting correlations. During this time we kept in touch with Patient Zero as well as other patients that had been diagnosed and getting treatment, to track their progress.

Through our research, we came across a compelling article showcasing how different disease categories could have striking overlaps in symptoms and underlying mechanisms. A patient who had been catatonic and institutionalized for two decades, initially diagnosed with schizophrenia, responded dramatically to immunotherapy and was ultimately found to have neuropsychiatric lupus—a severe autoimmune disorder affecting the central nervous system.

Investigating further, we noticed that conditions with overlapping symptoms to PSSD, such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, long Covid, and the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, were all linked to immune dysregulation and neuroinflammation. This was noteworthy considering neuroinflammation had also been linked to symptoms such as cognitive impairment and anhedonia—two hallmark symptoms of PSSD. Our early PET-scans, Cunningham panels, cytokine panels, and certain lumbar puncture findings, seemed to support this notion.

After over a year of tracking patient test results, It was now time take the next step, and put it all together.

A small group of patients, including Patient Zero, “Rightsentence”, Arcane and myself, formed an association called INIDA—short for “Iatrogenic Neuroimmune Disease Association”—dedicated to researching and raising awareness among patients and researchers regarding the “neuroimmune” aspect of PSSD.

Creating the Document

By mid-2023, I compiled our data into a structured document, preparing to present our findings to Professor Melcangi, whose research group has previously published several studies on PSSD.

What started as a simple compilation and interpretation of our data quickly evolved into a more comprehensive resource. It kept expanding in scope to include discussions around related diseases, investigations into the nervous system for contextual basis, speculative sections, treatment anecdotes as well as four case reports showcasing four different PSSD patients’ neurological work-ups with written statements by medical professionals.

Given the limitations of our data having not been collected in a controlled clinical setting, and the fact that we are laymen of these topics, we aimed to present the document as sort of a mix between a scientific paper and an investigative article, to make it accessible for both researchers and the patient community.

Arcane helped out in completing the first iteration, which was sent in early that summer to Prof. Melcangi. I quickly continued on the next iteration, expanding the scope over the following months, while also aiming to improve its quality. At this point two people from the association, Rightsentence and “Pacino”, joined in to help out with proofreading, feedback, ideas, references, and some additional writing. The deadline kept extending as this was a big undertaking for such a small team, never mind a team with individuals who are all severely compromised by this condition. A couple of proofreaders helped along the process with constructive feedback and ideas. After many months of hard work, we finally finished the 2.0 iteration at the end of January earlier this year, and we are now finally ready to share it with everyone.

We recently shared previews with various researchers and medical professionals over the past few months and the overall response has been great so far, so we hope this may be a sign that this effort has been worthwhile.

Our findings have been highly intriguing, showcasing strong links to small fiber neuropathy, dysautonomia, neuroinflammation, and gut dysbiosis, as highlighted by the infographic. We believe that these findings, combined with the anecdotal reports and our broader research, suggests that PSSD may be, at least in part, an immune-mediated neurological disorder.

With that said, these are just our own interpretations, and we want to make it clear that this effort is meant as a first step—to start a conversation—encouraging professional researchers to investigate these findings and their implications, and to hopefully try to replicate them in a controlled clinical setting. We need real scientific inquiry, not denial. This is a fight for truth, for proper research, and for justice for those suffering.

The goal here is not to make any bold claims about “having all the answers”. We simply want to point in a direction that is backed by verifiable data, numerous anecdotal reports and say “Hey, let’s investigate this further. Let’s have an open conversation”. What does the data indicate? How can this be further backed by the clinical presentation, established research, anecdotal reports on diagnostic work ups, diagnoses and treatment reports?

We simply want to make a strong case for researchers and community members to look at this and consider the implications, as well as provide a strong case for medical providers to see this as a legitimate and serious medical condition.

It’s up to researchers to pick up the mantle from here on.

As an end note I wish to thank everyone that contributed in some form to making this a reality; Arcane, RightSentence, Pacino, Ebigram, Yassie Pirani, Patient zero, Goldenhour, and everyone in the community that provided their lab results to us. I also wish to thank MIA for hosting this, and Jessie Drouin for connecting us.

Visit our website for more: https://inida.info

Thanks for sharing your story. Best wishes on your healing journey.

There seems large scale of ignorance that there are serotonin receptors throughout our body. It is of course poorly understood how SSRI work on our brain, much less the broader systematic effect through our entire body.

Report comment

Thank you, appreciate it.

Indeed it does. And that aspect is just one thing. From what we’ve seen it seems to make sense that a lot of these drugs that cause similar syndromes; PSSD, PFS and PAS (which have entirely different mechanism of action), may be (at least in part) an immune-mediated response to the drugs. But of course we cannot draw any conclusions until we get research on this.

Report comment

Let me show you something. These are the symptoms caused by MTHFR C677T homozygous (double) mutations…..

neuropathy, “brain zaps”, insomnia, sensitivity to stress, digestive problems, gastroparesis, IBS, bloating and constipation, chronic fatigue, akathisia, cognitive decline, hair loss, tinnitus, ear pain, hearing loss, atrial fibrillation, floaters, glaucoma, rashes/hives, hypersensitivity to medications, foods, spices, gluten, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac events, neurological and psychiatric disorders, clotting problems, migraines, hypertension, diabetes, renal failure, kidney stones, some cancers, hearing loss, autoimmune problems, psoriasis, heat and exercise intolerance, anemia, shortness of breath, mood swings, increased sensitivity to pain (caused by low BH4), brain fog, anxiety, hormonal imbalances

Other…More severe Covid, Lymes, MS, homosexuality, Parkinsons

I think you get the point. They match what you listed on your paper.

And here’s a paper linking MTHFR mutations and low Folate to depression, autism, ADHD, Bipolar, BPD, addiction, PTSD, schizophrenia, OCD, Parkinsons

https://www.scielo.br/j/jiems/a/85W3FTYFpKwKKXnFjvGWg3f/?lang=en&fbclid=IwY2xjawKP-VZleHRuA2FlbQIxMQBicmlkETFOdUplSkNoaHRmWnprUlI2AR5_ht-8bKcXZ_nLnrFWLCibLv3FpMM6LzeeDT5JmTMwlCP7suCOL9-QU21jHw_aem_T_57jR122DAeNy5O5934iw

After my son died by suicide, I too went looking for answers. When I joined a suicide survivors support group, I noticed right away that many of the suicide victims had the so called “Reward Deficiency Syndrome” conditions, autism, ADHD, Bipolar, BPD, addiction, PTSD, schizophrenia (at the time I didn’t know that depression and OCD belonged to the group).

I knew they shared a few things so I wondered if there were more things they shared and made a list. They ended up sharing many things. All have:

Neuroinflammation

Low Vitamin D

Dysbiosis

Methylation problems

Immune system problems

Oxidative stress

Histamine Intolerance

Inability to metabolize Folic Acid properly

When I found the last 2 I knew what I was dealing with. The one thing that can cause all the things on the list is MTHFR mutations.

I had written about them on a paper back in 2010

They cause low Folate, low Vit B12, low vitamin D, elevated homocysteine, abnormal lipids and SSRIs do the same thing. And you’re right, it will be the biggest scandal of the century because Big Pharma knew it.

Report comment

You are very modest, Jon, your research and efforts are very impressive. And, as one who was also, misjudged – in your case for stupid reasons, in my case for stupid and nefarious reasons – and harmed with the anticholinergic drugs. I hope you don’t mind if I link your story in a comment in yesterday’s article about the antidepressants, by Peter Simons.

I believe your story points out a very important reason why our society absolutely needs to stop psych neurotoxic poisoning all children, as well as all of child bearing age, who might possibly like to have children and live a normal life. God bless you in your healing and research journeys, Jon.

Report comment

Thank you, I really appreciate that.

No worries go right ahead if you want to post it somewhere.

That’s good to hear, this really needs to change.

Thank you, I’m sorry for your suffering as well and wish you all the best.

Report comment

Hallo Jon,

it’s simply impressive what you’ve researched and created despite this incredible overload.

May I also add that I believe MCAS, as a comorbid condition, could play a major role. Doctors don’t like to deal with that either, as histamine is too complex.

What these pills do to a person’s body is one of the greatest crimes one can commit against a human being. I view sexuality as the foundation of our existence on a much larger scale than we normally understand. It is truly our all-encompassing creative aspect. To dare to destroy this foundation and then to claim that it’s the first “disease” coming back, is a perfidious distortion of the facts.

I wish you every success in your work and, above all, recovery and restoration of your health.

Report comment

Thanks a lot, I really appreciate your kind words.

Yes indeed, MCAS is something we have also observed in some individuals.

Indeed.

Totally agree with you. This is the biggest scandal of our lifetime. The new “Lobotomy” of the 21st century.

Indeed.

Thanks a lot, I wish you the same as well.

Report comment

Thank you so much for bravely sharing your story. I can only imagine how isolating and exhausting it must be to live with PSSD for so many years, especially while feeling dismissed by the very professionals meant to help. Your honesty and vulnerability are incredibly important-not just for raising awareness, but for letting others in similar situations know they are not alone. I hope that as more people speak out, the medical community will listen and take action to research, validate, and support those affected by PSSD. You deserve compassion, understanding, and real answers. Wishing you strength and moments of peace as you continue on this difficult journey.

Report comment

Thanks a lot, I appreciate your kind words.

Yeah it’s been a helluva “ride” to put it that way. I’m just happy now that this is getting more and more recognition, and I feel hopeful about a turning point within the next few years.

Thank you so much.

Report comment

What Id like to know is is there a genetic marker that you share with others who suffer so tremendously from PSSD? I do know people react differently to psychotropic meds and have spoken with a young woman who wasted 10 years of her life on the wrong anti-depressants before she saw a Dr who gave her a genetic test that showed the ineffectiveness of those SSRIs on her. She did then find relief from her symptoms with other medications. We are all unique beings. I do hope that you make progress in the medical world. Do you have a website? My experience is similar with the benzodiazepine world – and I support a nonprofit at benzoreform.org that is trying to educate patients and Drs on the dangers of benzodiazepines. They have come up with a similar term, BIND for benzodiazepine induced neurological dysfunction. Same story with patients suffering from dozens of side effects. Keep up the good work and I do hope to hear more and read on a website about your work.

Report comment

Hi. There is probably some genetic predispositions, but regarding CYP tests (which I assume is what your friend got) is something several patients have had, and we didn’t really see any correlations with this.

Thank you I appreciate that. Yes we have a website; http://www.inida.info.

Ah yes benzo’s are notorious for their nasty withdrawals and iatrogenic harm. I shall check out the benzreform website .

Thank you for your comment.

Report comment

Great investigative, life giving work!

Pills or shots do not help everyone.

Forty five years ago, the Docs prescribed Benzodiazepines for the anxiety (caused by antidepressants?) together with the antidepressants!

Your journey parallels what I experienced for so long. Now, I CAN cry for what you are describing. I actually asked the doctors why I couldn’t feel anything. The response was, “You are no longer suffering,” (aka the human condition.)

Thank you for going the reaching back for the future people. You provide hope that one day we will test each person. You are shining a light!

I am horrified we are the trials. Keep healing.

Could blunting have anything to do with mass sh@@ting?

•get outside (vitamin D), get out of your head, stop self medicating or medicating, listen to sleep stories, eat well, love yourself, unplug and enjoy life! (for anyone that is reading my comment; been there/done that)

Report comment

I have always believed that the blunting effect contributes to the increase in both interpersonal violence and suicide attempts. Inhibitions serve an important purpose. If you are no longer worried what will happen if you shoot someone, it makes it more likely that those with such tendencies will do so. Same with suicide.

Report comment

Dear Jonny,

The same thing happened to Hepatitis C patients when they treated with interferon. Interferom is pro inflammatory, that’s how it elicits a reaction from the immune system. So it caused neuroinflammation and people became depressed and were prescribed antidepressants. I saw PSSD only once in a forum patient. Interestingly, he had an autoimmune condition prior to using interferon. He had psoriasis.

I made some comments on things in your paper. I hope they help you.

Fluoroquinolones… LOWERS FOLATE

Accutanne ….LOWERS FOLATE and Vit B12

SSRIs…….LOWER FOLATE, Vit D, Vit C

As a matter of fact, all the things that increase suicide risk LOWER FOLATE, like anticonvulsants, statins, malaria meds, TGondi, etc

Here’s a case of axonal neuropathy caused by Cipro. They were able to reverse it by treating early with Folic Acid.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6006604/

Folic Acid and B12 are essential for the process of methylation (Carbon 1 metabolism). The process responsible for recycling homocysteine and creating SAM-e and gluthatione.

SAM-e donates methyl groups (methylation) to aid in many important processes including:

synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA), DNA,

manufacture of neurotransmitters

histamine and lipid metabolism

cell growth and division

detoxification by the liver and more

When you dysregulate this process, it can cause HYPOMETHYLATION in the brain, OXIDATIVE STRESS and MITOCHONDRIAL DAMAGE.

This paper shows that the spinal degeneration you saw in scans is caused by oxidative stress.

https://www.archivesofmedicalscience.com/Antioxidant-therapy-in-the-management-of-Fluoroquinolone-Associated-Disability,97321,0,2.html

The picture with the yellow substance on the filter…that’s from bilirubin. (I work in dialysis).

Low Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) found in some of your cases..

Folate deficidency causes impaired remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and a decrease in SAM-e and both Folic Acid and SAM-e deficiency impair tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) biosynthesis. Cytokines reduce dopamine levels by diminishing the activity of BH4 and oxidative stress promotes irreversible degradation of BH4.

More later….

Report comment

Jonny,

I was right. It’s caused by MTHFR mutations and IT CAN BE TREATED! IT CAN BE TREATED!

“Methionine is a precursor for s-adenosyl methionine, the methyl donor needed to maintain the neuron sheath. Deficiency will impair methylation of myelin basic protein and lipids that CAUSES DAMAGE TO THE MYELIN SHEATH. This syndrome affects large, myelinated fibers, but it can also AFFECT SMALL FIBERS, such as the A delta (A) fibers that can carry pain sensation [16]. In addition to the mechanism of impact on the neuronal sheath, methionine synthase converts 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate for DNA synthesis. Therefore, a deficiency in vitamin B12 can affect DNA synthesis. In addition, in B12 deficiency, methyl malonic acid (MMA) and homocysteine levels can be seen to be elevated [16]. Although the deficiency in B12 methylation occurs one step after MTHFR in folate synthesis, it follows that a lack of MTHFR could also impair the pathways’ ability to methylate myelin basic protein and lipids that play a vital role in methylation and the health of the neuronal myelin.”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772973723009104

Also, MTHFR mutations also causes abnormal metabolism of alcohol.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your story with us. I’m so sorry for what you’ve endured over the years. SHAME on the doctors who arrogantly dismissed or denied that PSSD is a real medical condition. They say “when life gives you lemons, make lemonade,” and you have done just that with your thorough research and dedicating yourself to bringing more attention to this very real problem for thousands of people. It takes courage to expose the corruption and faults of a mental health system that is shaped by very powerful pharmaceutical companies. Keep speaking the truth and being the voice for those whose lives have been destroyed by PSSD.

Report comment

Thank you so much for your kind words.

Report comment

I think I struggle with this condition. My have been on Zoloft for the majority of my life, and have completely lost the ability to experience sexual pleasure and have no sex drive to speak of, and it feel completely numb emotionally and physically. I don’t feel my feelings the way I used to. I as trying to remember the last time I felt truly happy the other day, and realized it was years ago. I’d be interested in joining your PSSD community, if you’ll have me!

Report comment

This is incredible! Is there a link anywhere to the discord?

Report comment

“Visit our website for more: https://inida.info”

I am just a reader but their website is very sophisticated. I hope that helps.

Report comment