Against a backdrop of frequently hyperbolic regional news reporting about the “need” to involuntarily commit more people, in 2022, the Oregon government brought together a wide range of mental health system stakeholders for consultations. The stated goal: Come up with ideas to grapple with poor mental health system outcomes that appear to be related to psychiatric bed shortages and declining rates of involuntary commitment.

Surprisingly, this “Workgroup” reached 51 unanimous and generally constructive recommendations for change—illustrating what proponents and critics of forced psychiatric interventions can achieve through collaboration.

However, led by the Oregon branch of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, Treatment Advocacy Center, and a few hardline politicians, a splinter group instead proceeded to implement exactly what the Workgroup did not recommend: they expanded the legal criteria for civil commitment so that far more Oregonians can be incarcerated and forcibly treated.

The details of this story reveal much about the deceptive politics surrounding involuntary commitment in Oregon, and across America.

“Few Commitments! No Beds!” (And Lots of False Numbers)

The “Commitment to Change Workgroup” was convened by the Oregon Judicial Department (OJD), and an opening letter in its final (November 2024) report, “A Review of Oregon’s Civil Commitment System”, sets the stage: The OJD co-chairs lament the dearth of psychiatric beds and small numbers of people being committed. “A day rarely passes without media coverage of the impact of unmet behavioral health needs on our communities,” they write.

Indeed, calls to increase the numbers of psychiatric beds and expand civil commitment in Oregon have been ringing out from many news outlets. Journalists and their sources declare that civil commitment in Oregon is “nearly extinct.” They claim the number of people detained under civil (non-criminal) mental health laws is merely 517 people annually, or several hundred, or even as low as fifteen people in the entire state. And that’s largely because, the stories claim, the whole state of Oregon, with 4.2 million people, has a measly fifty beds to hold civilly committed patients—leading to rising homelessness, jail populations, drug use, and tragic violence.

If all of this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s a narrative promoted nationally and in virtually every state by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC)—organizations that have been spearheading expansions to forced psychiatric treatment around the country. And in Oregon, it’s no different—these news reports regularly quote or cite NAMI and/or TAC e.g. here, here, and here.

While effective at rallying support for more mental health funding, more beds, and more commitments (and more earnings for those in the business of psychiatric force), the numbers that TAC and NAMI tend to provide and that many politicians and journalists parrot are often either wildly misleading or blatantly false.

Yet notably, in Oregon unlike in some states, more accurate data is actually readily available. We’ll look at the real data and its importance shortly—but first, enter a high-profile government initiative to tackle the alleged problems.

A “Diverse” Workgroup—Except for the People Who Actually Matter

The Workgroup report states that OJD’s leadership selected Workgroup members “to represent a broad range of stakeholders in the civil commitment system,” including “courts, state agencies, legislators, local governments, Oregon tribes, health care providers, law enforcement, public defense and prosecution, and people with lived experience.”

Divided into 9 subgroups in a graphic in the report, at a glance the 24 members do appear to be reasonably diverse, and many represent key entities.

Upon closer examination, a heavy bias is evident. The Workgroup included 21 people representing agencies, organizations, and political parties that help implement civil commitment and/or have pushed for expansions to civil commitment, including the director of NAMI Oregon, and Jerri Clark, a staff member of Treatment Advocacy Center. (Even the Native American representative was Oregon Health Authority staff.) Meanwhile, there were just 2 attorneys who defend people facing commitment (from Disability Rights Oregon and the Oregon Criminal Defense Lawyers Association). And there was but one lone person representing consumers and survivors—those who’ve actually used the mental health system and may have been subjected to commitment themselves (Janie Gullickson from the peer-run Mental Health and Addiction Association of Oregon).

It’s difficult to fathom anyone daring to create a government multi-stakeholder workgroup to revamp the laws and services primarily affecting any specific population such as, say, people confined to wheelchairs, which included only one member of 24 who was in a wheelchair—but such is the socio-political reality in which we’re living with respect to people labeled as seriously mentally ill.

Nevertheless, the Commitment to Change Workgroup’s final, unanimous recommendations—although soft in language, riddled with key gaps, and hardly radical for critics of forced treatment—seem surprisingly useful in pointing to constructive pathways forward.

Recommending Due Process, Options, and Data

The Workgroup report acknowledges that reforming civil commitment processes often stalls due to “the consistent lack of consensus among those seeking reform.” Still, the Workgroup ambitiously agreed to aim for “consensus,” defined as “unanimous agreement” for its final recommendations. Many of those 51 recommendations can be loosely grouped by themes: strengthened legal due process; more options, and better data.

Some of the due-process recommendations also highlight how unfair current processes are. For example, the Workgroup recommends that people being committed should always be advised of their right to an attorney, and that defense attorneys should receive training on effective representation at commitment hearings. Currently in Oregon, many patients whose long-term commitments get renewed aren’t told of their right to an attorney, and few attorneys have specialized training. Experts like Jim Gottstein have estimated that proper legal representation alone could reduce commitments by as much as 90 percent, because so many are unconstitutional.

The Workgroup urges exploring the potential use of Psychiatric Advance Directives—in other fields of health care, people’s previously expressed wishes are respected, even if those decisions could cause debilitation or death (such as do-not-resuscitate orders), so why not in mental health care?

And the Workgroup proposes that “mental disorder” should be clearly defined in commitment law—since there are no lab tests or validated measurements, judges tend to defer to psychiatrists’ opinions, and so it’s virtually impossible to prove one does not have whatever disorder a psychiatrist claims one has.

The Workgroup also makes many recommendations for increasing choices and options for people who are committed, including allowing patients to more actively participate in treatment planning, elect non-medication treatment options and alternatives such as recovery-oriented therapies, and live in non-coercive, supportive residential homes. They also propose educating providers on ways to lessen tendencies to make commitment and treatment decisions based on racial, ethnic, sanist, and other prejudices.

And the Workgroup also endorses vital recommendations to collect better data—including more accurate total numbers of commitments and recommitments, and collecting and analyzing socioeconomic, demographic, and other information to help better understand who is being committed and why.

Although obviously not a call for abolishing all forced interventions, if implemented, such reforms could make meaningful, positive differences for many people who get committed, reducing harms now and helping inform future public policy decisions.

Meanwhile, other proposals for reform that did not achieve unanimity in the Workgroup are interesting and revealing—and some proved to be foreboding.

Let’s Instead Expand Commitment and Hide the Impacts!

Other sections of the Workgroup report provide behind-the-scenes insights into proposals that were supported by all but one Workgroup member, and proposals that were generally very divisive.

The Oregon Health Authority (OHA) was the lone veto vote on one otherwise unanimous recommendation:

- “Collect data to compare and report the types, quantity, and outcomes of treatment and services provided by counties to civilly committed individuals.”

As I discuss in my book on involuntary commitment, there are barely a handful of studies of outcomes in the world that even consider the question of whether psychiatric incarceration and inpatient forced treatment are effective at helping people in any way. Consequently, there’s also no evidence that commitment reduces self-harm, stops violence, improves quality of life, or achieves any of the grand claims frequently used to justify the severe abrogations of people’s rights and freedoms. A former head of the European Board of Psychiatry summarized that forced treatment is “based on tradition rather than evidence.”

And here in this Oregon Workgroup process we see clear evidence as to why so little data exists: Even when all others across the spectrum supported the idea, the government’s leading mental health authority would not agree to track and report on the outcomes of forced treatments.

Is this because they don’t want to see, or let the public see, how ineffective, distressing and traumatizing involuntary commitment often is? I asked OHA why they vetoed outcome tracking, but after three weeks a spokesperson tells me that OHA’s possible reply is “still going through the approval process.”

Another proposal before the Workgroup would have additionally—and sensibly—required collecting and analyzing such outcomes data before pushing government for specific changes to civil commitment legal statutes. This idea was resisted by even more Workgroup members, while some pushed two contrary suggestions:

- “Amend statute to lower the legal threshold for civil commitment.”

- “Amend the statutory criteria of “danger to self or others” to consider not only past behaviors but also predicted harm.”

These proposals to allow more people to be committed more easily were polarizing in the Workgroup, and ultimately were not put forth as recommendations. But what soon became evident was that some Workgroup members weren’t going to accept that. These pro-force members apparently believed they already knew that Oregon’s main problems are that there are virtually no psychiatric beds and hardly anyone gets committed—and they were going to make sure their arguments held sway with legislators.

This, even though the actual data shows those proponents of expanding force are not only wrong, but staggeringly wrong.

How Many Psychiatric Beds Does Oregon (Truly) Have?

Coaxed along by an oft-cited TAC report, many proponents of forced treatment argue that closing large asylums caused a “catastrophic” decline in the numbers of psychiatric beds in America. But TAC’s report only counts state hospital beds. Across America, massive public and private investments have gone into building smaller psychiatric facilities—inpatient institutions as well as locked and unlocked residential facilities.

So while news stories citing TAC and NAMI frequently claim that Oregon has just fifty psychiatric beds for civilly committed patients—or 1.2 state hospital beds per 100,000 people—most Oregonians detained under civil mental health laws today are held in other purpose-built psychiatric facilities.

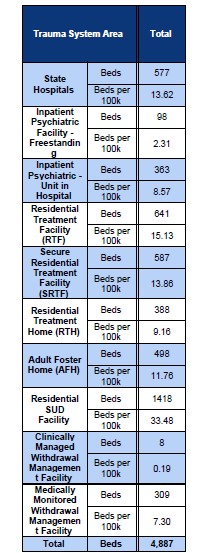

A report commissioned by the Oregon Health Authority, “Behavioral Health Residential+ Facility Study,” provides a more accurate count (see table). Oregon has 577 state hospital beds (though currently only a small percentage hold civilly committed patients). There are also 1,689 more psychiatric beds in other secure psychiatric facilities where civilly committed patients are held—in psychiatric hospitals, psychiatric wards in general hospitals, and locked psychiatric residential treatment facilities.

Adding in less-secure facilities, such as unlocked residential treatment facilities and adult group homes licensed specifically for people labeled with mental illnesses, the number of available psychiatric beds jumps to more than 3,152. And this is especially relevant because, in Oregon, hundreds of people annually are transferred to these or other less-secure facilities while they remain civilly committed and under forced treatment orders—they’re called “trial visits.”

If locked and unlocked facilities for substance use treatment are included, the number jumps to 4,887 total psychiatric beds. That’s about 116 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people, or nearly one hundred times as many beds as news media in Oregon have typically reported.

But even those are low-end estimates. Oregon has many other locked and unlocked facilities with beds for people labeled with mental illnesses that the report authors didn’t count but argued should in future be included in the count, including:

- Psychiatric institutions and facilities for children and youth

- Community Hospitals

- Supported Housing

- Facilities licensed by local rather than state government

- Facilities licensed by the Oregon Department of Human Services

Those bed numbers could also be substantial. For example, the Oregon Department of Human Services oversees tens of thousands of beds in long-term care facilities. Many of those beds are identified as occupied by people labeled with “serious” and “severe and persistent” mental illnesses—these add another 5,545 psychiatric beds, or 132 beds per 100,000 people. (If we were to include beds occupied by people diagnosed with clinical depression, those numbers would more than triple.) And any of these can, in principle, hold civilly committed patients on long-term “trial visits.”

So, with at least 248 psychiatric beds per 100,000 people—and nowhere near done counting—Oregon has 200 times as many psychiatric beds as news media have typically reported, and more than existed in Oregon asylums in the 1950s.

And that’s why far more people can be committed today in Oregon than is generally publicly acknowledged, too.

How Many People (Actually) Get Committed in Oregon?

In tandem with the many news stories, even the Workgroup report’s opening letter from the OJD co-chairs puts the annual number of civil commitments in Oregon as low as “roughly 500.”

Yet according to data from the OJD itself, the number of civil commitments annually is sixteen times higher, at nearly 8,000. (See OJD’s Data Dashboards and Circuit Court Statistics > [Year] Circuit Court Case Statistics > Cases Filed > Civil Commitment)

What’s going on?

The “roughly 500” number—as the Workgroup report itself later explains, but virtually none of the news stories do—represents only those people who get committed long term, for 180 days, each year.

But under Oregon commitment laws, a person can forgo a hearing and agree to take prescribed psychotropics for 14 days, in exchange for avoiding the risk of a 180-day commitment. In 2023, that was 1,016 more people.

And then there were people who got subjected to psychiatric incarcerations and possible forced treatment that lasted up to five days—in Oregon, these involuntary holds are euphemistically called a ”Notice of Mental Illness” and, in 2023, these comprised an additional 6,500 incarcerations.

So, far from being unusually low, Oregon’s rate of psychiatric incarcerations of about 8,000 annually, or 190 incarcerations per 100,000 people, is near the national median.

And that’s nearly double the UK rate and far higher than most comparable European countries.

And there are more.

In Oregon, unlike in other states, 180-day commitments can be renewed repeatedly and never generate a new judicial record unless a patient demands a hearing. Consequently, the year-over-year cumulative number of Oregonians truly under long-term civil commitments—after being transferred to any of the thousands of available psychiatric beds—is currently unknown. (News reports have sometimes cited a peer-reviewed article by three psychiatrists claiming the number of civilly committed people in Oregon has undergone a “dramatic decline” to mere hundreds annually; however, the study didn’t include involuntary holds, and lead author Thomas Hansen acknowledged to me in an email that they also did not count long-term recommitments. Their study actually “did not attempt to quantify how many people were currently civilly committed,” Hansen wrote.)

As occurs in many states, there may also be many people who get detained for hours or days but are let go before a judicial record is generated.

Furthermore, none of 14,000 Oregonians under guardianships are counted—yet a common use of guardianships is to coercively treat people labeled with mental disorders.

So, in summary, if there’s a “crisis” in Oregon’s civil commitment system, it cannot be because there are practically no beds and hardly anyone’s getting committed. And this fact raises questions.

Could the real problem be that coercive interventions have become too common and aren’t helping, or are making things worse? Could it be that, under the current medicalized mental health system, few people ever recover, so beds are ever filling? Maybe more expensive beds and locked facilities aren’t what’s needed—but instead better voluntary community services and affordable, supportive housing?

These are vital questions—but ones which NAMI Oregon, TAC, and a few politicians apparently had no intention of considering.

Sabotage

Before the Workgroup process was even completed, as a Workgroup member, NAMI evidently saw what was going on and did a political end-run: NAMI wrote its own draft bill that ignored the Workgroup’s unanimous recommendations and instead dramatically expanded the criteria for civil commitment. NAMI even gave its bill an air of authority and legitimacy by telling the public it came from a multi-stakeholder “workgroup” on civil commitment.

Meanwhile, according to the OJD Workgroup web page, Democratic Representative Jason Kropf was “leading a legislative workgroup to develop…potential legislation… related to civil commitment… including proposals arising from ideas presented in the Workgroup Final Report.”

So, what happened?

In April of 2025, Kropf, Republican Senator Kim Thatcher, and Democrat Senator Floyd Prozanski—all members of the OJD Workgroup—brought an adapted version of NAMI’s bill forward as HB 2467 and SB 171 (both bill overviews state “for National Alliance on Mental Illness”).

I reached out to all three, asking why they’d ignored all of the 51 unanimous recommendations of the very government Workgroup of which they’d been a part, and instead were pushing these changes that were not recommended.

On June 5th, a Legislative Aide for Prozanski emailed to me that the bill was introduced merely as a “courtesy” to NAMI, and “was filed but not heard… before our deadline for committee action.” The Legislative Office Director for Thatcher similarly assured me that the bill “did not receive a hearing or work session” and “will not advance this session.”

Just eleven days later, though, Prozanski and Kropf folded an adapted version of the text of the NAMI bill into another bill, HB2005, and rushed it into law in several days with virtually no public consultation.

Kropf didn’t respond to my queries about it.

More Force, More Locked Facilities

Unlike what the OJD Workgroup recommended, HB2005 uses broad terms to expand civil commitment criteria in Oregon to allow capturing more people.

Since predictions of “dangerousness” are unreliable, to commit someone, judges sometimes require evidence that a person is immediately or “imminently” dangerous to self or others—however, the new Oregon statute instructs judges that people can be committed even when any potential risks to themselves or others are “not imminent.” If it’s merely “reasonably foreseeable” that a person may behave in ways that could be harmful “in the near future,” they can be committed. Or, if there’s “any past behavior” that suggests harms could occur, people can be committed.

The new statute also makes it easier to order long-term forced treatment. It instructs judges to consider forcible treatment based on a lengthy list of possible concerns “including but not limited to any of the following”—such as whether the person is likely to voluntarily take treatments, or whether, without treatment, the person might deteriorate in some way. Strikingly, the statute also appears to dispel with any requirement to establish that a person ‘lacks insight into their mental illness and need for treatment’ (the most common rationale used to justify forced treatment), instead stating that judges should consider committing a person if either of “the person’s insight or lack of insight” makes them less likely to take treatments.

Another bill, also originally drafted by NAMI, will put $65 million into building new secure residential facilities to hold more committed people.

In reaction to the passage of these bills, David Oaks, a psychiatric survivor and founder of MindFreedom Oregon, stated, “We have been hit by a steamroller.”

Oaks might as well have been talking about what happened to Oregon’s democratic process itself thanks to NAMI, TAC, and a few politicians.

MindFreedom Oregon is forming a coalition (contact [email protected]) to push back against the changes. Ironically, the government’s own Workgroup report could be held up as a shining example of what should happen—and should never have happened.

***

MIA Reports are supported by a grant from Open Excellence and by donations from MIA readers. To donate, visit: https://www.

Wow, this is a damning report, thank you, Rob.

As one who has recently researched into narcissism, who dealt (and hopefully is no longer dealing, but I don’t yet know for certain) with a narcissist psychologist.

I will forewarn all psych survivors, about the narcissistic – and downright criminal – behaviors of the now scientifically debunked DSM deluded “psych professionals.”

Mind Freedom, I will try to get our donation to you soon, thank you for all you do.

Report comment

“So, far from being unusually low, Oregon’s rate of psychiatric incarcerations of about 8,000 annually, or 190 incarcerations per 100,000 people, is near the national median.

“And that’s nearly double the UK rate and far higher than most comparable European countries.”

Isn’t that evidence of the systemic crimes of today’s “BS” US psych industries?

Report comment

civil: 1.

relating to ordinary citizens and their concerns, as distinct from military or ecclesiastical matters.

“civil aviation”

commitment: the state or quality of being dedicated to a cause, activity, etc.

“the company’s commitment to quality”

!? What does this have to do with aviatory companies?

I went to the beach, and someone I won’t bother to mention since she’s already harassed beyond recognition, she didn’t like a thread of citrus rind, so she had thrown it off. One of the seagulls, after I called them into a murmur flew down making me think it had seen something that only looked like what it was after, but no, it was edible. It actually was that thread of rind. Having not thrown off with it, I jabbed my fingers nails into making bite sized pieces and sure enough they went for it. I was a bit surprised that, when you throw other things down for them to gobble up, they then might either fight about it, or are acting as if. But in the air, they always are beautiful in their murmurings.

“In the Bible, “murmur” primarily means to complain in a low, muttering voice, often out of discontent or dissatisfaction, especially against God or those in authority. It’s a sin that is frequently associated with grumbling, fault-finding, and a lack of faith in God’s provision or guidance. ”

And then: “A murmuration is a spectacular aerial ballet performed by large flocks of birds, most notably European Starlings, characterized by their synchronized and fluid movements, twisting, turning, and swirling in unison.”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0sE10zUYyY

What is civil commitment? What is civil about it?

I think it’s quite simple. There’s a difference between art and artifice. Art has content, artifice doesn’t. Or don’t believe me and go to your nearest museum and marvel at all of the frames the paintings are in, but DO NOT actually look at the paintings, that’s idolatry. Then study the building but DO NOT look at the people inside, or take in what they are doing, that would be blasphemy. Then study the streets, the layout of the city, and maybe even go as far as the airports, or NASA’s pad for launching things into outer space, but DO NOT… Do not what?

Report comment

Rob, Have you tried following the money with TAC and Dr Torrey and anyone else affiliated with wanting more oppression of any marginalized others? I am thinking of private companies. My grand father was in danger with his union activities and for awhile had to deal with the Pinkertons.

I would imagine private equity plays a role and the idea would be increase the bed count in whatever way you can. And since anyone other than the powers that be is less than – life commitment is seen as good for business and who really cares? This is so much part and parcel of Eugenics and Jim Crow and other isms that the Nazis studied for their planning of the Third Reich. South Africa another place with needed papers and segregated racial categories. Ghandi started his work in South Africa.Always others.

Dr Torrey has been underground yet omnipresent and from old articles and having read one of his first books his turn doesn’t make sense. There has to be more somehow. I do not understand.

Report comment

Hi Mary,

It would be great for someone to do an investigative deep dive into the history and workings of TAC, but on the surface at least their influence has been in the opposite direction: With hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from a pro-force billionaire (whose child was labeled with bipolar), Torrey’s “Stanley Medical Research Institute” and TAC have funded others, not vice versa. Some trace Torrey’s turn from self-proclaimed antipsychiatry activist into leading advocate of forced treatment to his sister being institutionalized, and then getting that influx of financial support–Torrey doesn’t exactly dispute this, but he also claims psychiatric science got better.

On other issues, there are a number of sections in my book, Your Consent Is Not Required, in which I do ‘follow the money’, and find significant financial interests in civil commitment. For example, the mental health industry as a whole pulls in some two hundred billion dollars annually in America alone, and those orgs and companies lobby and fund politicians heavily. Hospitals can make a lot of profits from commitments–to the point of some doing it in the form of large-scale fraud. Private equity is heavily invested in group homes, nursing homes, and other places patients are placed. etc.

But I felt I was just skimming the surface, and there’s likely much more to expose in terms of who profits. That said, in countries like Canada and the UK with much less presence of private interests in public health, the same trends are evident–so there’s cultural ‘buy-in’ to this approach, too.

Rob Wipond

Report comment

One flew over the cuckoos nest was there

Report comment

Thanks for your kind reply Rob. And yes other countries similar issues but not as much for profit I would assume.

One almost needs to have not only a time line but maps of congregate living situations.

And I was unable to read your book to many connections to read without stress.

And layers of not only financial but cultural issues. So in my previous state many of the individual group homes run by immigrants. And with immigration there is no tool to access what is the history of this area. So Cleveland was a center for immigration from Appalachia , from Germany up to and including Post World War II, Central and South America, Mexico abd Puerto Rico, India , and Vietnam and the Philippines along with being a city for The Great Migration and Relocation Center for indigenous peoples and post internment Japanese.And then when Nixion brought China into diplomacy many Chinese students at universities.

We all are just realizing this and no lessons, no tools, but commitment process part of social control . And varying degrees of improvements then slides back .

Then the whole how much is trauma how much other things and vets and their systems that work and sometimes don’t work at all another layer. Again mapping out the old and new VA places might be helpful. Where and when.

Please do more work. And yes I knew about the history but it still seems a mystery to how various people are influenced to end up harming versus helping . One does not see this force in families with developmental disabilities as much. The push for commitment.

One really needs to do a whole other study of families and anyone not in the middle of the bell shape curve. And now many times these folks now in the commitment fear track or worse being killed track.

Then caretakers and the history and economic matters . Both family and professional and I am thinking not only group homes and nursing homes but school sides.

Salaries and benefits like further training. So many things just so interrelated hard to see the individual strands.

Report comment

Thanks Rob for shining a spot light on the corruption in Oregon. I would like to point out that Oregon’s Governor Kotek, despite her status as a member of the LGBTQ community, does not appear to be sympathetic to the individuals who belong to another marginalized community: C/S/X. Even though, as recently as four decades ago, people who identified with being gay or lesbian were thought to have a mental health disorder, Ms. Kotek, having enjoyed the privileges bestowed on her, partly by gay and lesbian activists who resisted against organized psychiatry, are in fact, unable or unwilling to help bestow the same privileges upon those who are still stigmatized by the DSM labels such as ‘schizophrenia’ or ‘bi-polar’

In fact, I believe she and her partner are extremely corrupt. First, she practiced nepotism by putting the ‘first lady’ her partner, on the payroll as her chief advisor, then both of them, in knee jerk attempt to follow up on Kotek’s grand campaign promise to ‘end homelessness in Oregon’, apparently thought that they could accomplish this by rounding up all the ‘crazies’ and medicating them against their will. She went so far as to grant special access to Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a division of Johnson & Johnson, the manufacturer of the biggest most popular drug used by Oregon’s civilly committed, a depot injectable ‘anti-psychotic’ drug called ‘Invega’ which coincidentally, was the drug that was forced on two of the most recent individuals in Oregon who were centered in a MindFreedom Shield campaign.

https://www.wweek.com/news/2024/05/16/new-emails-show-first-lady-provided-a-pharmaceutical-company-high-level-access-to-key-state-official/

Kotek packed the C2C committee with like-minded stakeholders such as Treatment Advocacy Center, NAMI, and public safety officers, and shut out the voices of people with lived experience throughout the entire 2-year legislative formation stage. Now that the new law is in effect, consumer/survivors will continue to be shut out of the implementation process unless we fight back. Anyone who is reading this who lives in Oregon right now, if you want to fight back against Kotek and her big pharma buddies, send me an email right away! We are organizing at this writing! My email is [email protected]

Report comment

Apparently the forth, fifteenth, and possibly, the fifth amendments of the US Constitution are allowed no standing here. How, exactly, can this be?

Report comment

I knew the information out there was not complete. As someone with both a BA in journalism and a career in mental health (with lived experience) I appreciate both the careful work here and your reasoned approach (why let the facts in the room!) I was not aware of the full contingent of that task force and that sole consumer member (old term, I’m sorry) deserves a freaking year long scholarship for therapy for having gone thru that experience of probably hitting her head against the wall while up against such heavy hitters. I see in my head her playing tic tac toe for Everytime someone said “well it will benefit them by getting them off the streets” or, even better, ” Forced anti psychotic will help them. ” Actually the recommendations they came up with sound ‘” same”. Question: while I could see who was speaking a lot in the press, when that happened, how were the others reacting? When things started going off the rails, I mean these were professionals with agency, lawyers and such, why did no one say anything? And this information about the beds and such, why are we getting this now? With Oregonian politeness of course

Report comment