I look in the mirror and ask myself—what am I more: a writer or a war-traumatized veteran?

Which came first?

Who is the person typing this essay?

And why does it matter?

Because a writer can invent a world—any world he wants.

But the traumatized man?

He only wants to write one world—his.

I don’t write about the trauma.

The trauma writes me.

Every time I sit at the computer, it shows up.

Not always right away.

Sometimes it lets me type a few quiet lines—then it pulls up a chair.

Not shouting. Whispering.

Uninvited.

It tries to take over.

Not me—the character.

I try to build someone else: a protagonist who is calm, intact, untouched by war.

Someone who knows love, boredom, ordinary fear.

But the trauma rewrites him.

It revises his backstory.

It plants in him the wounds of a soldier.

It floods him with anxiety.

It forces him to face what I tried to escape—my own fear.

And suddenly, the character—no longer entirely mine—carries my scars.

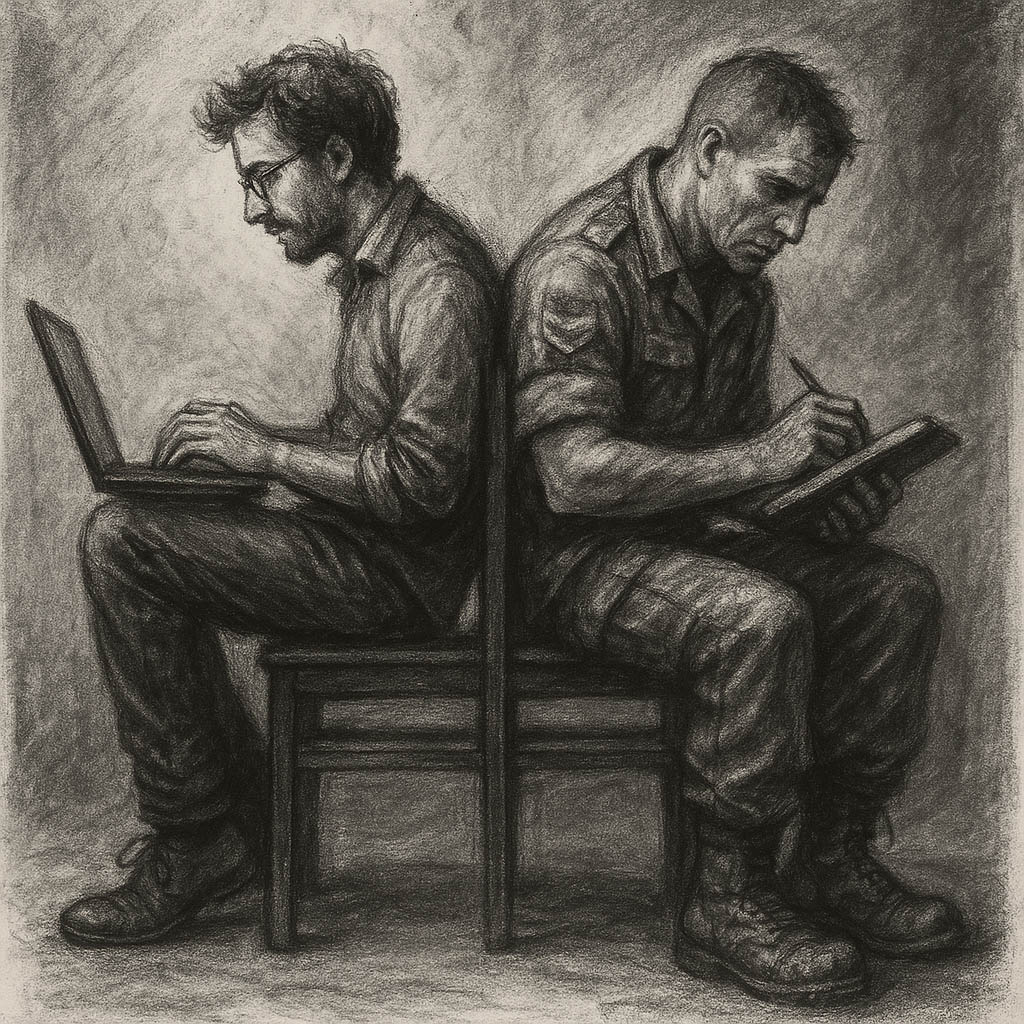

It’s not a war between memory and fiction.

It’s a war between two voices.

The writer’s voice: it shapes, composes, imagines.

And the trauma’s voice: raw, insistent, unfiltered, breaking in.

One seeks structure.

The other wants to blow it apart.

The writer writes.

The trauma erupts.

In my first novel, Holiday Apocalypse, the protagonist—a writer—meets a wicked dwarf who offers him a deal that’s hard to refuse.

He wants what many writers want: success, fame, admiration.

But then, without warning, the instincts I learned in the army begin to surface.

The training.

The reflexes.

The way war etches itself into your nervous system.

It bleeds into the narrative.

I tried to write about ambition.

The wounded man in me hijacked the plot.

Suddenly the character drinks.

He uses drugs.

He fights enemies that aren’t there.

And the novel shifts.

It’s no longer about ego—it’s about fracture.

A man who can’t tell the difference between memory and madness.

Because something inside him is still at war.

In my second novel, Dog, I didn’t resist.

I surrendered in advance.

Let him speak.

The shell-shocked veteran got the mic.

The writer stepped aside.

No metaphors.

No protection.

Only trauma—raw, howling, unfiltered.

There was no “me” in Dog.

No voice left to shape.

Only a wound, begging to be read.

Even in the novels that followed, the swordfight never stopped.

Book after book—character against creator.

Didn’t matter if the protagonist was a Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis or a chimpanzee fluent in sign language.

The same battle played out.

The trauma pulled toward itself.

The writer pulled toward story.

And in between—a character torn in two.

When does it end?

When does the writer hold the pen steady, and the trauma sit quietly in the shadows?

When I write for children.

Something changes then.

The child walks onto the stage—the child from before.

Before the war. Before the injury. Before the silence.

He tells a story.

Simple. Pure. Full of wonder.

And the trauma has nothing to say.

Because it hasn’t been born yet.

That’s the only voice unafraid.

Maybe this is the core of my writing:

Not choosing one over the other,

but learning to live in the tension.

To be both.

The man who remembers.

And the man who imagines.

To let them share the page.

Sometimes, even the same sentence.

Because sometimes, from that fracture, a deeper truth appears—

One that can’t be faked.

Not perfect.

Not heroic.

But honest.

And in the end, that’s all I have to give.

To not engage

the poet, the traveler,

the wounded warrior

in all of us

We, The People

of

The Tribe

wonder now

the forced commitment

to

the

Left Margins

Difficult to block

for the natural

the gap

in

carrying

the LIGHTS

this way

that way

within the Brilliance

of Human,

knowing moment

Engaged!

Report comment

Dear Bill,

Your words found me

like a soft wind moving through the ruins,

like a whisper from someone who’s been there too.

Yes. The poet, the traveler, the wounded warrior, we meet in the margins.

Not as strangers.

As kin.

Thank you for carrying the light, even when it flickers.

Thank you for seeing mine.

With respect and quiet awe,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

Yishay Ishi Ron writes not just with honesty, but with a kind of naked courage that few writers dare to reach for.

The image of the trauma “pulling up a chair” beside the writer is haunting and unforgettable. It’s not melodrama, it’s metaphor as truth. And that recurring tension between the writer and the wounded man, between fiction and involuntary memory, gives this piece a heartbeat.

Another great work, Yishay!

Report comment

Dear Ann Marie,

Your words touched me more than you know.

To write with naked courage, I think that’s the only way I can. There’s no armor left, just the chair beside me, and whatever I can shape from what still trembles.

Thank you for seeing the heartbeat between the lines. For listening not only to the story, but to the wounded man behind it.

Your encouragement means the world.

With gratitude,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

Thank you, Yishay for sharing such a moving account of how trauma can shape one’s inner life.

I especially appreciate your naming the tension it imposes—the way it sits beside you as you try to reclaim your own voice. You’ve given the life-long process of integrating trauma the time, respect and dignity it deserves.

What I value most is that you haven’t let psychiatry hijack and rename your experience. You’ve kept the language—and the authority—where it belongs: with the one who lives it.

Report comment

Dear Birdsong,

Your words feel like a hand placed gently on the shoulder, steadying, recognizing, reminding me that I’m not alone in this long walk.

Thank you for honoring the tension, for understanding what it means to sit across from trauma and still try to speak in your own voice. That quiet rebellion, refusing to let others rename your pain is for me, an act of survival.

I’m grateful you saw that. And I’m grateful for you.

With warmth and deep respect,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

I’ve read your previous posts on madinamerica. I’m not you. I’m not inside your head. I sometimes wonder if you shouldn’t write directly about your trauma. Not from a litterary point of view, just for you to heal. Maybe perhaps without publishing it (or publishing an expurged version, or anonymously). I had told you in a previous that traumas heal with self-compassion and guilt blocks compassion ; so you would give a special importance to guilt. You wouldn’t be a writer that creates his own reality for his fun, rather you would be a slave to your own reality ( of guilt and trauma). What unites the soldier and the writer is this trauma. I’m sure you already thought of it. I think it would be a liberation.

Report comment

Dear Jean-Philippe,

Your comment stayed with me.

I’ve thought a lot about what you wrote, that perhaps I shouldn’t write literarily about my trauma, but rather just for myself, without the burden of audience. You’re right: there is a cost to turning pain into story. A risk of shaping it too soon, or of hiding behind craft when the wound is still open.

But writing even when it’s public, has been, for me, both a mirror and a rope. I don’t think I write to entertain or escape. I write because otherwise the trauma owns every word. This way, I get to speak first.

And yes, guilt. It’s the shadow that sits quietly at the edge of every page I write. Maybe what unites the soldier and the writer isn’t just trauma, but the war between guilt and grace.

Thank you for challenging me. Thank you for staying with the work.

With respect,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

I can’t imagine the pain and difficulties you are facing.

War leaves such a wound that it cannot heal.

But it seams like you have found your outlet.

Im in a search for my.

I have lost my son a four years ego and since then, im stuck in the sadness, it take control of me every second.

The balance you are talking about is inspiring.

Thank you!

Report comment

Dear Mila,

Your message broke something open in me.

I can’t pretend to understand the pain of losing a child. That kind of grief lives beyond language. But I can say this: I hear you. I honor your sorrow. And I’m so sorry.

Yes, writing has become my way through the darkness, not to escape it, but to walk inside it with a light in my hand. Some days the light flickers. Some days it goes out. But the act of reaching for it again, that’s what keeps me going.

I hope you find your outlet, your voice, your way. And if you ever do, even just a small part of it, I hope you know: it matters.

Thank you for your bravery in writing to me.

With tenderness and respect,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

I’ve found both painting, and writing, to be helpful in healing from trauma. So I wouldn’t avoid getting the evil out, via your creative expression of choice, Yishay … get the evil out, so you may move on.

As I think I mentioned to you earlier, I do so hope we may soon end WWII for the Israelis. The never ending wars need to end … for all of us.

Report comment

Thank you for your kind and thoughtful words. I agree, art, whether on canvas or on the page, can be a way to move the darkness out of us and make space for something lighter.

I share your hope that we will see an end to these long and endless wars. May we all find the peace we’ve been searching for, in our countries, and in ourselves.

With gratitude,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

Look mate, the solution to ‘mental health’ is not in pill form – it is in love. And love ain’t some beauty contest. Love is seeing things as they are. Except there is no they – only that// So love is us being who we are, and love is that seeing of who we are in our freedom. So love is being and seeing who we are in our freedom and in that freedom, in the freedom that contains no we or they but only that. That nothingness is love. It is seeing and all is in this seeing. The seen is unreachable. And the seeing is too unreachable. Ignorance scales the mountains between the two. And I know everything in it, so I know everything, but it is nothing, because in it is no thing. There is only the infinite, the perfect, the pure, the formless and the emptiness that hides all existence within itself. Or to you it hides itself within all existence. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t have a name… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKPpD7q76eM

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your perspective. I agree that love, real, unadorned, and grounded in seeing each other as we are, is at the heart of healing. Your words are a reminder that beyond all labels, there’s a deeper freedom we can still reach for.

With appreciation,

Yishay Ishi Ron

Report comment

Thanks for your insights, they help all women who suffer incest, rape, job and street harassment and the other horrors that unfortunately do not stop with wartime. Our voices too want to default to the horrors but also transcend them. You articulated what many of us haven’t untangled yet, since the enemies and injuries change but don’t stop. I suppose a bunch of outraged male shitposts will call this off-topic because war is hell, but oh well, they’ll never get it that women live with fear and abuse that’s normalized but still damaging. Thanks to this writer for helping separate injury from all the rest that we can be.

Report comment

Dear Val,

Thank you for your powerful words. What you wrote touched me deeply. You are absolutely right, war is not the only battlefield, and the injuries women endure in daily life are no less real, no less scarring.

I believe literature and testimony have the power to name these wounds and also to point toward something beyond them. If my writing helped in any small way to articulate what is often left unsaid, then I feel I am doing the work I need to do.

Your voice matters, and your response reminds me why we must keep speaking, even when others dismiss it as “off-topic.”

With respect and solidarity,

Report comment