In this article I will take a closer look at two statements by leading psychiatrists (Olfson, 2025; Strawn & Walkup, 2025) in response to the criticism about psychiatric drugs raised by “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) (The White House, 2025). Without doubt, there are good reasons to be critical of MAHA. For example, as I am writing this (22. September 2025), the US Department of Health and Human Services suggested explanations for the seeming rise in autism based on poor arguments and at odds with the evidence. Some statements by Robert F. Kennedy are bizarre and not consistent with evidence based medicine. In general, the eroding of democracy and fascisic changes in the US and in other countries are deeply concerning, and this includes attacks on scientific freedom and the foundation of scientific reasoning.

When criticizing MAHA, this should be done with scientific rigor. Furthermore, scientists need to be open to arguments independent of who bring the issues forward. For this reason, manuscripts are often blinded for peer review. In this regard, political divides aside, there likely would be consensus about the importance of topics in the MAHA report, such as childhood obesity, overprescription, or the problematic influence of the pharmaceutical industry. One topic in the MAHA report is the harm/benefit of psychiatric drugs for children and adolescents, including antidepressants. Indeed, for antidepressants, which is the focus of my article, there is evidence for overprescription and a long-standing debate within evidence based medicine about whether their benefit can be considered clinically meaningful and outweigh harm (Cipriani et al., 2016; Hengartner, 2021; Hetrick et al., 2021; Jakobsen et al., 2019; Munkholm et al., 2019).

After the release of the MAHA report, influential psychiatrists have published responses in scientific journals. I was struck by the sometimes poor arguments and biases regarding antidepressants in these responses. Since this is an area where I published myself and have some knowledge of the evidence base, I decided to publish my viewpoints on the responses by leading psychiatrists (Olfson, 2025; Strawn & Walkup, 2025).

“Psychotropic medications and child health” by Marc Olfson, JAMA Pediatrics

When discussing antidepressants, Olfson focuses on the issue of suicide risk. I agree with Olfson that “depression is a key risk factor for suicide.” But he is wrong in how he selects and interprets evidence about the suicide protective effects of antidepressants. He wrote: “The NIMH Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study [TADS] demonstrated that fluoxetine, especially when combined with cognitive behavioral therapy, can reduce suicidal thoughts.”

As pointed out by child and adolescent psychiatrist Dr. Lyus in a commentary, Olfson misrepresents the findings for suicide ideation in the TADS study. In fact, there was a near zero difference between fluoxetine and placebo, and a modest superiority of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) alone and CBT combined with fluoxetine, compared to placebo (effects sizes ca. 0.3). Therefore, authors of the TADS concluded: “Suicidal ideation decreased with treatment, but less so with fluoxetine therapy than with combination therapy or CBT” (March et al., 2004).

Moreover, Olfson also ignored the findings for suicide attempts in the TADS study, which are the more important “hard” outcome, telling more about actual risk for suicide than suicide ideation. In fact, there were significantly more suicide attempts with patients on fluoxetine (alone or in combination with CBT) than patients not on fluoxetine (CBT alone or placebo).

Furthermore, by using the TADS study, Olfson is ignorant of the biases in psychiatric research, because the TADS study seems to be a case-in-point example. For example, in a separate publication of suicidal events occurring in the TADS study (Vitiello et al., 2009), the outcome for patients treated with fluoxetine were spun (see here for a detailed account). The TADS authors reported that suicidal events, of which 55% were associated with hospitalization, were not significantly elevated in patients on fluoxetine (14.7%, n = 16) than placebo (10.7%, n = 12). However, as later pointed out by Högberg et al. (2015), “it is of note that of those 12 placebo cases, 9 subjects were in fact taking fluoxetine medication.” For suicide attempts, this means that only 1 suicide attempts occurred in patients treated without fluoxetine, versus 17 suicide attempts in patients treated with fluoxetine. Only in a footnote in a table of the original publication it was mentioned that with a correct classification, suicidal events occurred significantly more often in patients with fluoxetine vs. placebo or CBT only. Högberg et al. also presented an overview about how the findings for suicidality were spun in the abstracts of the original TADS publications. In addition, very recently the “Restoring Invisible and Abandoned Trials” (RIAT) re-analysis of the TADS study was published, and it again revealed biases and spin (Aboustate et al., 2025). The RIAT team found that “In contrast to the original TADS Team’s reporting, there was a higher level of harm uncovered in allocation groups taking fluoxetine, including 11 unreported suicide-related adverse events.”

Olfson also omitted to mention that fluoxetine’s efficacy shrank into the range of clinical equivalence with placebo in a Cochrane meta-analysis from 2021 (Hetrick et al., 2021). This important finding has generally not been acknowledged in recent guidelines which still refer to outdated reviews of the evidence (Plöderl et al., 2025). Of note, in the Cochrane meta-analysis, the efficacy findings for other antidepressants were underwhelming as well, and there was also a small but statistically significant increase of suicide attempts among children and adolescents treated with SSRIs compared to placebo.

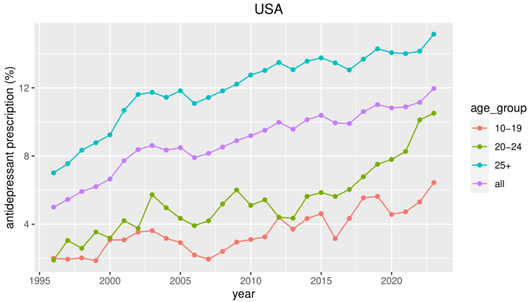

When Olfson discusses the putative harmful effects of the FDA black box warning, he seems one-sided and uncritical about the evidence supporting the view that the warning led to an increase of suicides in young people due to reduced prescriptions. He references a systematic review of correlational and ecological data (Soumerai et al., 2024). Fortunately, Olfson addresses methodological limitations for this type of study. However, Olfson should also have been aware that important studies in this review have been debunked and that there is contradictory evidence (Spielmans et al., 2020; Stone, 2014, 2018). For example, one study included in the review (Lu et al., 2014) reported an increase of drug-poisonings after the black box warning. However, as immediately pointed out by commentators in the BMJ or in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stone, 2014), the authors used drug-poisonings with any intent (suicidal vs. nonsuicidal). When using intentional drug-poisoning as the more appropriate outcome, there was actually a decrease of such events after the black box warning. Moreover, the results of the statistical modelling approach (interrupted time series) are sensitive to the selection of the time-frame around the black box warning and the timing of the warning itself (Stone, 2018). Using a longer-time frame contradicts claims of a harmful effect of the black box warning (Plöderl & Hengartner, 2023). Instead, longer-term trends of antidepressant prescriptions and suicides leads to the conclusion that the black box warning became ineffective, given the increasing prescription rates and also suicides rates since the warning (see Figure). Finally, such observational/ecological data are inherently limited and cannot replace findings from the gold-standard randomized clinical trials which revealed significantly increased rates of suicide attempts in the drug arms, at least for SSRIs (Hetrick et al., 2021). Given the short-term nature of clinical trials and the rarity of suicides and suicide attempts, a look at observational studies is useful, despite their methodological limitations. Here, an increase of suicide attempts and even suicides with SSRIs vs. no treatment with SSRIs in well-controlled observational studies judged to be of high quality was found (Barbui et al., 2009; Dragioti et al., 2019). Consequently, even when considering uncertainty, the evidence does support the view that antidepressants increase suicidality in young people, and that the black box warning is justified.

Olfson warns that “Downplaying the established effectiveness of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents, while overstating their risks, can lead to serious consequences.” But it seems he is biased too, just in the opposite direction. He could be blamed for exaggerating the effectiveness of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents, while downplaying their risks, which can harm patients and damage the reputation of evidence based medicine.

“Fact versus Fear” by Jeffrey Strawn & John Walkup

Strawn and Walkup present strong claims such as “When opinions trump scientific data and clinical pragmatism, children suffer the consequences, and clinicians are placed in a bind. Put simply, clinicians are faced with a dilemma: to adhere to clinical evidence and treat when appropriate with appropriate caution, or yield to opinion, anecdotal data, and political pressures.” Who would disagree that clinicians should follow the science and not political pressure. Clinicians also need access to unbiased summaries of the evidence and it seems that Strawn & Walkup don’t do a good job here.

They directly start with the black box warning as example of unintended consequences of “fear and alarm, despite that there were no suicides in the clinical database” and “too few actual attempts to identify any between-group differences,” so that the FDA had to mix any suicidal events, that is, suicide ideation and suicide attempts combined.

This suggests that a treatment related increase of suicide ideation alone does not warrant a black box warning. While this can be debated, Strawn & Walkup fail to mention evidence that there is also a significant increase of actual suicide attempts with SSRIs vs. placebo, as later confirmed in meta-analyses (Hetrick et al., 2021; Stone et al., 2009). It is also not surprising that no suicides occurred in the trial database, as suicides are rare events, especially in this age-group, and the trial database is underpowered to detect a signal for suicide. However, as already mentioned, a significant increase for both suicide attempts and suicides was reported in high-quality, well-controlled observational studies (Barbui et al., 2009; Dragioti et al., 2019). All this confirms the FDA’s decision to issue a black box warning.

Strawn & Walkupp write: “In hindsight, these concerns were prescient. Following the boxed warning, antidepressant prescriptions for youth dropped sharply,3 and suicide rates rose significantly in untreated adolescents.4“

Both claims are not supported with the selective and outdated evidence Strawn and Walkup use. Reference #3 is a study by Nemeroff et al. (2007), which only looked at the time to 2005. In our study where we looked at a longer time-frame to search for changes in trends of suicides, we could not detect change points in line with the assumption that the black box warning increased suicide rates (Plöderl & Hengartner, 2023). A change in the trend of suicide rates already occurred before the black box warning (around 2000) and the fluctuation seen around 2004 are compatible with noise. The decline in prescriptions was short-lived and both prescription rates and suicide rates started to rise again afterwards.

For the claim that “suicide rates rose significantly in untreated adolescents,” Strawn and Walkup reference to a study by Gibbons et al. (2012). However, this study is not about untreated depression at all, but is a meta-analysis of clinical trials investigating fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Interestingly this study reported that “For youths, no significant effects of treatment on suicidal thoughts and behavior were found,” and “The marginal ORs indicated a 61.3% decrease in the probability of suicidal thoughts or behavior for control [placebo] patients after 8 weeks of study participation and a 50.3% decrease for treated patients.” So referencing this study not only doesn’t make sense because it is not about untreated depression but it also confirms that treatment with antidepressants is not helpful or even harmful regarding suicidality as outcome.

Strawn & Walkup then go on with “The unintended, but resultant, stigmatization of antidepressants and their prescribers is the lasting legacy of the boxed warning. Perception of the actual risk has morphed from suicidal thinking to an impression of more serious risk —“suicidal behavior” which can be interpreted as attempts and deaths.”

This claim implies that the actual risk associated with antidepressants does not extend to suicidal behavior. But this is wrong, as there is evidence from reviews of clinical trials for an increase of suicide attempts (vs. placebo) and evidence from observational studies regarding suicide attempts and suicides (vs. no treatment) in the treatment with antidepressants (see references above). None of this evidence is mentioned by Strawn and Walkup. Furthermore, a look at the ever increasing antidepressant prescriptions does not suggest that stigmatization is a problem. On the contrary, as already mentioned, this trend could support the view that the black box warning became ineffective and also that the finding of the poor efficacy of antidepressants is not acknowledged.

They then have issues comparing antidepressants with psychotherapy: “Medications may be more effective for addressing physiological symptoms (eg, insomnia, appetite disturbance), while therapy targets behavioral and cognitive dimensions (eg, avoidance, distortions).” Interestingly, they don’t give a reference here. They also ignore the fact that for their example of insomnia there is significantly increased risk in young people treated with antidepressants than with placebo (Türkmen et al., 2025). Gastrointestinal issues are also occurring more frequently with antidepressants than with placebo (Jakobsen et al., 2017). Given the minor benefit of antidepressants over placebo and these side effects, it may be more favorable to treat the two examples of physiological symptoms with placebo or non-pharmacological approaches. At least we lack data to support their view.

There is also no reference for the claim that “For some children with anxiety, OCD, and depression, medication, even medication monotherapy, may be the appropriate first-line treatment, not a fallback.” If the goal is to be more evidence based, then such a statement should be framed as opinion or supported with evidence.

Strawn and Walkup go on with a positive evaluation of the efficacy of SSRIs: “For example, fluoxetine, as the first SSRI brought to market, has the most robust evidence base.18–22 In terms of this evidence for the use of SSRIs in depression, in one of the most methodologically rigorous studies of an SSRI in adolescent MDD, both fluoxetine and fluoxetine combined with CBT were more efficacious than unblinded cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and a blinded placebo.16“

Again they referenced an outdated meta-analysis and ignored more recent findings. They also only cited the first few RCTs on fluoxetine with favorable results but not the 9 more recent trials of which 5 failed to be statistically significant and efficacy of all 9 trials were largely in the area of equivalence with placebo (Plöderl et al., 2025). They also misrepresent findings from the TADS study. The meta-analysis they reference is Cipriani et al. (2016), where fluoxetine was the only antidepressant which was significantly superior to placebo. Cipriani et al. concluded: “When considering the risk–benefit profile of antidepressants in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder, these drugs do not seem to offer a clear advantage for children and adolescents. Fluoxetine is probably the best option to consider when a pharmacological treatment is indicated.” Anybody really familiar with Cipriani’s meta-analysis should know that the certainty of the evidence for fluoxetine (but also for other antidepressants) was judged to be “very low,” and this is quite different from a “very robust” evidence interpretation as judged by Strawn and Walkup. Therefore, in contrast to Strawn & Walkup, Cipriani et al. actually give a sobering view on the efficacy of antidepressants.

Furthermore, similar to Olfson, Strawn & Walkup do not mention that a more recent meta-analysis found a substantially smaller overall efficacy for fluoxetine, being now clinically equivalent with placebo (Hetrick et al., 2021). In our own re-analysis of the trial data for fluoxetine we provided potential explanations why efficacy melted down in the clinically irrelevant range (Plöderl et al., 2025). Initially, fluoxetine was investigated by the sponsor (Eli Lilly) or authors with ties to the sponsor, and fluoxetine was only compared to placebo. These trials were positive. Later, fluoxetine was used as a comparator drug in trials done by competing companies or by the same company but for a competing drug (duloxetine). Moreover, later trials often had 3 or 4 study arms, which means that the chance to receive placebo is smaller (< 50%) than in the initial trials (50%) and this could have led to different expectancy effects, impacting efficacy estimates (Plöderl et al., 2025). Of note, fluoxetine is the only antidepressant which was used as a comparator in pediatric depression trials. No other drug was put to test as a comparator so far, and this is important when judging the efficacy of other antidepressants. We also found another explanation for the larger efficacy of fluoxetine in the influential early meta-analysis by Cipriani et al. (2016). They included a small outlier trial with erroneous/impossible results which boosted the efficacy of fluoxetine. This remained undetected in Cipriani’s study and caused inconsistencies which remained unexplained. Once this problematic trial was removed, the inconsistencies within Cipriani’s meta-analysis disappeared, and the results were then comparable with the recent Cochrane meta-analysis from 2021 (Lyus et al., 2025).

Strawn & Walkup are optimistic regarding other antidepressants, at odds with what Cipriani et al. 2016 concluded: “However, despite the strong data supporting fluoxetine in MDD, this doesn’t mean it is the ‘best.’ Rather, fluoxetine is one of a class of medications, many of which are likely to be effective across these conditions. While there are subtle differences among SSRIs, such that one might be better than another for a particular patient, they are likely all effective, albeit supported by fewer trials or trials of lower or questionable quality.23,24”

This interpretation ignores that all other antidepressants were never put to test with other antidepressants (at least for the treatment of depression) and it is thus not fair to compare these drugs with fluoxetine. Strawn and Walkups’s optimistic view on the efficacy of antidepressant not only are at odds with the sobering conclusion in Ciprian’s meta-analysis, but also with the more recent Cochrane review from 2021 which concludes that: “Findings suggest that most newer antidepressants may reduce depression symptoms in a small and unimportant way compared with placebo. Furthermore, there are likely to be small and unimportant differences in the reduction of depression symptoms between the majority of antidepressants.”

Regarding adverse events, Strawn and Walkup write: “Many adverse effects parallel pre-existing symptoms of anxiety, OCD, and depression, which makes it hard to distinguish between the disorder and the drug”—This is an awkward argument because results from randomized controlled trials are not affected by such confounding, and drug-placebo differences in adverse events, which occur more frequently with antidepressants than with placebo, can be causally attributed to effects of the drug.

They continue with “it can be difficult for patients and families (and for clinicians) to differentiate the symptoms of their condition from the adverse effects of the new medication.”

I agree, and this is why we need randomized controlled trials. However, I believe that patients and clinicians can in principle differentiate treatment emerging symptoms unrelated to previous experiences of the mental health problem. In my opinion, the problem is rather that strong prior beliefs about medication can lead to biased evaluations of side effects. With restricted time for thorough assessments and with clinician biases in favor of the medications they prescribe, adverse events caused by the medication tend to be falsely attributed to the mental health problem.

Strawn and Walkup state that “Perhaps the most pragmatic reflection of tolerability is discontinuation. Across trials, SSRI discontinuation rates are similar to placebo.”

This is true but not the full story. It is known that in antidepressant trials, discontinuation due to adverse events occurs more frequently in antidepressant arms than in placebo arms. Discontinuation due to lack of efficacy events occurs more often with placebo than with the drugs. Therefore, and not surprisingly, antidepressants are less tolerable than placebo with respect to adverse events. Furthermore, the fact that drop out rates are about the same in drug arms and placebo arms is, in my opinion, a rather disappointing finding. In fact, drop-out occurs slightly more in drug arms than placebo arms; 31 vs. 29% in adult trials and 18% vs. 17% in pediatric samples (Stone et al., 2022). If antidepressants are truly safe and effective, one would expect a lower drop-out rate in the drug arms than in placebo arms.

In the discussion of adverse events, Strawn and Walkup discuss the assessment of suicidality: “the FDA’s boxed warning on antidepressants was largely informed by studies that lacked structured assessments of suicidality and had a number of additional methodologic limitations.1 The studies included in these analyses relied on spontaneous reporting to a generic prompt or single-item dichotomous queries on symptom rating scales,2 which limited both interpretability and clinical applicability.”

I agree that the assessment of suicidality has limitations, but the interpretation is misleading. The crucial question is what this means in terms of related biases and it seems that Strawn and Walkup are ignorant of the available research. In fact, important evidence about biases in medical research originates from antidepressant research, including research on bias for suicidality as adverse events in clinical trials. For example, the RIAT re-analysis of Study 329 found that suicide ideation and suicide attempts were underreported and misclassified in the original publication, and that there was a larger paroxetine-placebo difference for suicidal events than reported in the original publication (Le Noury et al., 2015). I recommend readers to read more about Study 329, which continues to be a problem because the original (ghostwritten) publication with misleading results is still not retracted or corrected, leading to the absurd situation that two coexisting publications of the same data-set with two different conclusions coexist: in the original publication, “Paroxetine is generally well tolerated and effective for major depression in adolescents” (Keller et al., 2001), while in the RIAT reanalysis the conclusion was “Neither paroxetine nor high dose imipramine showed efficacy for major depression in adolescents, and there was an increase in harms with both drug” (Le Noury et al., 2015).

Another study compared study reports with publications and found that suicidal behavior was often misclassified into “emotional worsening,” and in one instance, a patient in the drug arm who died several days after trying to strangulate himself arm was classified as after-study event despite that the patient died in the double blind phase (Sharma et al., 2016). Another re-analysis showed that some suicidal behavior occurring in the placebo washout phase before randomization were nonetheless counted into the placebo arm of the double blind phase and this biased the drug-placebo differences, which in fact actually showed an elevated risk for suicidal behavior in the drug arms (Healy & Aldred, 2005).

When Strawn and Walkup raise methodological issues, it seems they implicitly suggest that the actual drug-placebo differences in suicidality is perhaps not so problematic. However, the available evidence suggests that the drug-placebo differences in clinical trial publications are underestimations of the actual increase of suicide risk associated with antidepressants. This is in line with findings from meta-research in medicine which suggests that the harms of treatments are generally underestimated in trial publications (Golder et al., 2016). Underreporting of harms perhaps peaks for sexual dysfunctions, a common adverse event of SSRIs and SNRIs, where clinical trials relying on spontaneous reports found much smaller drug-placebo differences than systematic assessments, where up to 80% reported sexual dysfunctions with SSRIs, compared to 12% with placebo (Serretti & Chiesa, 2009). A similar issue occurred in a study by Strawn et al., too: while there was no increase of treatment emergent suicidality with escitalopram versus placebo based on spontaneous reports, a statistically elevated risk occurred for systematically assessed suicidality.

Strawn and Walkup are correct when they criticize that adverse events are assessed with dichotomous items (adverse event present/absent), as this leads to a loss of information, for example about the degree of severity. In contrast, efficacy is usually assessed with fine-grained symptom rating scales. This leads to the situation that similar drug-placebo differences in benefit and harm are more likely statistically significant for benefit than for harm. We need to consider this by lowering the bar for evidence on adverse events.

Another problematic claim is that “Critically, the analyses also failed to establish a mechanism of risk [for suicide]. of risk, which makes the boxed warning even more problematic, as there is no obvious clinical mitigating factor to implement.”

This is again an awkward argument as clinical trials are not intended to establish mechanisms of benefit or harm. What can be inferred from randomized clinical trials is that drug-placebo differences are caused by the drug. Moreover, it is old clinical wisdom, which is also supported by evidence (Jakobsen et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2016) that antidepressants can cause agitation, akathisia, irritability, sleep problems, and aggression (in children and adolescents). In a depressed state, these side-effects can make the situation unbearable and can trigger acute suicidality. While this is rare, it nonetheless can happen and for this reason, close monitoring is necessary when starting antidepressants. Unfortunately, adequate monitoring is rather the exception than the rule, as known from a recent excellent register study from Norway on adult patients (Hansen et al., 2024). While guidelines recommend follow-up within two weeks for depressed patients starting medication, only one in four patients was followed up by a general practitioner or specialist within two weeks.

Then Strawn and Walkup are cherry picking: “In addition, subsequent investigations have not replicated the original signal and even have suggested that some SSRIs may decrease the likelihood of suicidality.12”

They reference a network meta-analysis of pediatric anxiety disorders only, where, compared to placebo there was a significant increase of treatment emergent suicidality for duloxetine, a reduced risk for sertraline, and no significant difference for any other antidepressant. Strawn and Walkup are very selective in presenting evidence and ignore the other subsequent investigations of clinical trials which did replicate the increased risk for suicide ideation and suicide attempts combined, but also suicide attempts (see references above).

Strawn and Walkup state that “Lastly, the risk was very low compared with the benefit,39 a fact that is often overlooked and sometimes even exaggerated in our discourse.”

This statement is especially noteworthy when considering a recent publication of Strawn himself, where he was “overlooking” harms and exaggerating efficacy (Strawn et al., 2023). In this study on escitalopram for pediatric generalized anxiety disorder, the primary outcome, reduction of anxiety symptoms was just below the magic threshold of statistical significance, but with a small effect size. An independent FDA analysis of this trial found that the primary outcome was not significant in some planned sensitivity analysis (Food and Drug Administration, 2023), but this was not reported by Strawn et al. Of note, none of the six secondary outcomes (response or remission on different symptom scales) were statistically significant and in fact close to zero or numerically even in favor of placebo. When I say that Strawn overlooked harm, I mean that in his study publication, treatment emergent suicidality was reported in the results section, but no statistical test was run and it was not discussed in the results section at all. This caught my attention and a statistical test showed that treatment emergent suicidality occurred significantly more often with escitalopram than with placebo (Plöderl, Horowitz, et al., 2023): “relative to treatment with placebo, 8% more patients treated with escitalopram developed suicidal ideation (1.5% placebo vs. 9.5% escitalopram) but only 6.2% more patients achieved clinical response (33.3% vs. 39.5%) and 1.5% fewer achieved remission (17.7% vs. 18.8%).” Consequently, in our letter to the editor, we concluded that ”relative to placebo, children and adolescents exposed to escitalopram were more likely to become suicidal than to experience an improvement in anxiety.” Moreover, there were significantly more adverse events other than suicidal ideation with escitalopram than with placebo (55.5% vs. 37.5%). The conclusion by Strawn et al. that “Escitalopram reduced anxiety symptoms and was well tolerated” is therefore at odds with the actual findings and the conclusion should be that escitalopram likely has a problematic benefit-harm ratio for the average patient.

More problematic claims by Strawn and Walkup:

“Subsequent studies, including registry data from Sweden and meta-analyses of placebo-controlled trials, suggest that suicidality may actually decline following the initiation of antidepressant treatment. In a large Swedish registry study (N = 538,577), suicidal behavior peaked during the month before starting an SSRI and declined thereafter.40 Specifically, the risk of suicidal behavior in the 30 days before SSRI initiation was more than 7 times higher than the risk during the same period 1 year earlier. In contrast, the 30 days following SSRI initiation were associated with a significantly reduced risk across age groups.”

This study using Swedish registry data does not say anything about the effects of treatment, as there was no control group. We pointed this out in our letter titled “Learning About the Course of Suicidal Behavior but Not About the Effects of SSRIs” (Plöderl & Hengartner, 2022). A study which used the same Swedish register data, but with a case-crossover control design found an increased risk for suicide at initiation of SSRI, especially in the second week after initiation (Björkenstam et al., 2013).

So, Strawn and Walkup cite a single observational study without a control group but missed to cite systematic reviews of observational studies. As already mentioned, high quality observational studies showed an increased risk for suicides and suicide attempts in depressed children using antidepressants (Barbui et al., 2009; Dragioti et al., 2019). In our own systematic review of observational studies on antidepressant for adults, we also found an increased risk for suicidal behavior among those treated with antidepressants (Hengartner et al., 2021). Moreover, we again found evidence for biases favoring antidepressants in these observational studies (Plöderl, Amendola, et al., 2023). First, there is clear evidence for publication bias, that is, studies with favorable results for antidepressants are selectively published. Second, studies with favorable results for antidepressants occur more frequently in psychiatric journals (this is not surprising, as we also experience that inconvenient findings are often rejected in mainstream psychiatric journals). Third, studies with authors who had financial ties to the pharmaceutical industry reported more favorable results for antidepressants compared to studies with authors without such ties, and this was independent of study quality.

“In addition, several placebo-controlled trials, including TADS and CAMS, have shown that suicidal thinking tends to decline across all treatment arms, including placebo.”

Again, Strawn and Walkup misrepresent the findings from the TADS study, where suicidal events occurred more often in children and adolescents treated with fluoxetine than with placebo or CBT only and that there was no significant drug-placebo difference in the reduction of suicide ideation (see comments to Olfson).

Strawn and Walkup argue that suicidality is often caused by the psychiatric illness and psychosocial stressors, not by antidepressants and that “linking medication use as a direct cause of suicidal thoughts and behaviors reduces a complex phenomenon to a misleading narrative.”

Here I agree with them, because the increased relative risk for suicidality found in clinical trials is small and this supports the view that most suicides are independent of harmful effects of the drugs. Nonetheless, and despite the inherent uncertainty in the evidence base, the evidence for an increased risk for suicidality associated with antidepressants in children and adolescents should be taken seriously, and this fully justifies the black box warning. Moreover, with the minor, clinically irrelevant benefit of antidepressants (at least for the majority of patients), even minor harms or severe harms in few patients are problematic, especially in light of inadequate monitoring after initiation of antidepressants (Hansen et al., 2024).

“Unfortunately, it [the black box warning] has also contributed to clinician hesitancy among pediatric primary care clinicians who are often at the front lines of the mental health crisis.”

Again, this statement is at odds with the evidence, as antidepressant prescriptions have increased in all age-groups since the black box warning in Europe (Fassmer et al., 2025) and in the US (Chua et al., 2024), reaching an all time high in the US (see Figure).

Spreading hope, not fear

A common argument in responses by both Olfson and Strawn & Walkup is that untreated depression is far more dangerous than the discussed harms associated with antidepressants. Nobody would argue that depressed people should be left without support or “untreated.” However, in my experience, all too often “treated” is equaled with “prescribing antidepressants,” and there seems to be a widespread automatism in prescribing antidepressants, driven by the assumption that antidepressants are safe and effective and that “something must be done,” and because of a seeming lack of alternatives. With the known poor efficacy of antidepressants and their harms, alternatives to antidepressants should be offered more often, such as watchful waiting, or basic interventions such as sleep management, light exposure, etc. (Selalmazidou & Bschor, 2023).

With the repeated claim that untreated depression is most dangerous, critics of MAHA are doing the same fear-mongering as proponents of MAHA do for the harms of the drugs. Usually, authors who claim that untreated depression is super risky either did not reference related studies or they misrepresent the evidence. For example, cited studies often did not investigate untreated patients or even showed a lower risk for untreated versus treated patients (Raven, 2019). Of course confounding by indication can explain why untreated patients have a better outcome than treated patients, but nonetheless these studies have been misinterpreted by those who want to point out the harms of untreated depression. Taking the evidence seriously would mean that we don’t know very much about untreated depression. However, the few available studies show that people who do not seek treatment fare well in the longer term (Whiteford et al., 2013). And as repeatedly pointed out above, treatment with antidepressants hardly outperforms treatment with placebo, at least for the majority of patients. Thus, instead of spreading fear we should provide hope. And this is evidence-based hope.

In contrast, we read alarmist messages in the article by Strawn and Walkup: ”The threat is not the medication. The threat is untreated psychiatric illness,” or “While SSRIs are not without limitations, they are clearly preferable to past treatments such as tricyclic antidepressants and far better than no treatment at all.” Again, no references are given.

The claim that treatment with SSRIs is “far better” than no treatment is also at odds when compared to what patients would expect from antidepressants. In a first study of this sort on adults done recently (Sahker et al., 2024), patients were informed about the harms and costs of antidepressants and then asked what minimum of efficacy they would expect to outweigh the costs/harms (“smallest worthwhile difference”), measured as expected increased chance of achieving response compared to no treatment. It turned out that for the majority of patients antidepressants fared below this smallest worthwhile difference. For context, this study was rather careful not to describe the full range of harms of antidepressants (e.g., the actual frequency of sexual dysfunctions or withdrawal issues). Finally, when psychiatrists are asked what they would do themselves when becoming depressed, most would not start with an antidepressants, but most would nonetheless recommend antidepressants to patients (Mendel et al., 2010).

Conclusion

I titled this article “A Call for Evidence-Based, Fear-Free Practice.” This call was used in a header by Strawn and Walkup in their paper. Unfortunately, it seems the two responses by leading psychiatrists are at least as biased and fear-mongering as the MAHA reports, just in the opposite direction. Both articles are published in scientific journals and it is telling that they passed peer review. Scientists need to do better by separating beliefs from evidence and by embracing facts, uncertainty, and critical views.

References

Aboustate, N., Jureidini, J., Woodman, R., Le Noury, J., Klau, J., Abi-Jaoude, E., & Raven, M. (2025). Restoring TADS: RIAT reanalysis of the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study. The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine, 9246479251337880. https://doi.org/10.1177/09246479251337879

Barbui, C., Esposito, E., & Cipriani, A. (2009). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of suicide: A systematic review of observational studies. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 180(3), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.081514

Björkenstam, C., Möller, J., Ringbäck, G., Salmi, P., Hallqvist, J., & Ljung, R. (2013). An Association between Initiation of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Suicide—A Nationwide Register-Based Case-Crossover Study. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e73973. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073973

Chua, K.-P., Volerman, A., Zhang, J., Hua, J., & Conti, R. M. (2024). Antidepressant Dispensing to US Adolescents and Young Adults: 2016–2022. Pediatrics, 153(3), e2023064245. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-064245

Cipriani, A., Zhou, X., Del Giovane, C., Hetrick, S. E., Qin, B., Whittington, C., Coghill, D., Zhang, Y., Hazell, P., Leucht, S., Cuijpers, P., Pu, J., Cohen, D., Ravindran, A. V., Liu, Y., Michael, K. D., Yang, L., Liu, L., & Xie, P. (2016). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 388(10047), 881–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30385-3

Dragioti, E., Solmi, M., Favaro, A., Fusar-Poli, P., Dazzan, P., Thompson, T., Stubbs, B., Firth, J., Fornaro, M., Tsartsalis, D., Carvalho, A. F., Vieta, E., McGuire, P., Young, A. H., Shin, J. I., Correll, C. U., & Evangelou, E. (2019). Association of Antidepressant Use With Adverse Health Outcomes: A Systematic Umbrella Review. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(12), 1241. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859

Food and Drug Administration. (2023, December 5). Multi-disciplinary Review and Evaluation LEXAPRO (escitalopram) tablets / oral solution. https://www.fda.gov/media/170239/download?attachment

Golder, S., Loke, Y. K., Wright, K., & Norman, G. (2016). Reporting of Adverse Events in Published and Unpublished Studies of Health Care Interventions: A Systematic Review. PLOS Medicine, 13(9), e1002127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002127

Hansen, A. B., Hetlevik, Ø., Baste, V., Haukenes, I., Smith-Sivertsen, T., & Ruths, S. (2024). Variation in general practitioners’ follow-up of depressed patients starting antidepressant medication: A register-based cohort study. Family Practice, cmae063. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmae063

Healy, D., & Aldred, G. (2005). Antidepressant drug use & the risk of suicide. International Review of Psychiatry, 17(3), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260500071624

Hengartner, M. P. (2021). Evidence-biased antidepressant prescription: Overmedicalisation, flawed research, and conflicts of interest. Springer.

Hengartner, M. P., Amendola, S., Kaminski, J. A., Kindler, S., Bschor, T., & Plöderl, M. (2021). Suicide risk with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other new-generation antidepressants in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75, 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214611

Hetrick, S. E., McKenzie, J. E., Bailey, A. P., Sharma, V., Moller, C. I., Badcock, P. B., Cox, G. R., Merry, S. N., & Meader, N. (2021). New generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2021(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013674.pub2

Högberg, G. N., Antonuccio, D. O., & Healy, D. (2015). Suicidal risk from TADS study was higher than it first appeared. The International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine, 27(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.3233/JRS-150645

Jakobsen, J. C., Gluud, C., & Kirsch, I. (2019). Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder? BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, bmjebm-2019-111238. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111238

Jakobsen, J. C., Katakam, K. K., Schou, A., Hellmuth, S. G., Stallknecht, S. E., Leth-Møller, K., Iversen, M., Banke, M. B., Petersen, I. J., Klingenberg, S. L., Krogh, J., Ebert, S. E., Timm, A., Lindschou, J., & Gluud, C. (2017). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMC Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1173-2

Keller, M. B., Ryan, N. D., Strober, M., Klein, R. G., Kutcher, S. P., Birmaher, B., Hagino, O. R., Koplewicz, H., Carlson, G. A., Clarke, G. N., Emslie, G. J., Feinberg, D., Geller, B., Kusumakar, V., Papatheodorou, G., Sack, W. H., Sweeney, M., Wagner, K. D., Weller, E. B., … Mccafferty, J. P. (2001). Efficacy of Paroxetine in the Treatment of Adolescent Major Depression: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(7), 762–772. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200107000-00010

Le Noury, J., Nardo, J. M., Healy, D., Jureidini, J., Raven, M., Tufanaru, C., & Abi-Jaoude, E. (2015). Restoring Study 329: Efficacy and harms of paroxetine and imipramine in treatment of major depression in adolescence. BMJ, h4320. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4320

Lu, C. Y., Zhang, F., Lakoma, M. D., Madden, J. M., Rusinak, D., Penfold, R. B., Simon, G., Ahmedani, B. K., Clarke, G., Hunkeler, E. M., Waitzfelder, B., Owen-Smith, A., Raebel, M. A., Rossom, R., Coleman, K. J., Copeland, L. A., & Soumerai, S. B. (2014). Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: Quasi-experimental study. BMJ, 348(jun18 24), g3596–g3596. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3596

Lyus, R., Naudet, F., van Valkenhoef, G., & Plöderl, M. (2025). A Re-Appraisal of Three Network Meta-Analyses to Explain the Discrepancy in Findings for the Efficacy of Fluoxetine for the Treatment of Depression in Children and Adolescents. MedRxiv, 2025.09.07.25334757. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.09.07.25334757

March, J., Silva, S., Petrycki, S., Curry, J., Wells, K., Fairbank, J., Burns, B., Domino, M., McNulty, S., Vitiello, B., Severe, J., & Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) Team. (2004). Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 292(7), 807–820. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.7.807

Mendel, R., Hamann, J., Traut-Mattausch, E., Bühner, M., Kissling, W., & Frey, D. (2010). ‘What would you do if you were me, doctor?’: Randomised trial of psychiatrists’ personal v. professional perspectives on treatment recommendations. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(6), 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078006

Munkholm, K., Paludan-Müller, A. S., & Boesen, K. (2019). Considering the methodological limitations in the evidence base of antidepressants for depression: A reanalysis of a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(6), e024886. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024886

Olfson, M. (2025). Psychotropic Medications and Child Health. JAMA Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2025.3024

Plöderl, M., Amendola, S., & Hengartner, M. P. (2023). Observational studies of antidepressant use and suicide risk are selectively published in psychiatric journals. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 162, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.07.015

Plöderl, M., & Hengartner, M. P. (2022). Learning about the course of suicidal behavior but not about the effects of SSRIs. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(4), 803–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01224-x

Plöderl, M., & Hengartner, M. P. (2023). Effect of the FDA black box suicidality warnings for antidepressants on suicide rates in the USA: Signal or noise? Crisis, 44(2), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000843

Plöderl, M., Horowitz, M. A., & Hengartner, M. P. (2023). Re: “A Multicenter Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Escitalopram in Children and Adolescents with Generalized Anxiety Disorder” by Strawn et al.—Concerning Harm–Benefit Ratio in a Recent Trial About Escitalopram for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 33(7), 295–296. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2023.0029

Plöderl, M., Lyus, R. J., Horowitz, M., & Moncrieff, J. (2025). The loss of efficacy of fluoxetine in pediatric depression: Explanations, lack of acknowledgment, and implications for other treatments. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/wk4et_v1

Raven, M. (2019). 24 Untreated mental illness: Ideology trumps evidence, fuelling overdiagnosis. Oral Presentations, A18.2-A18. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2019-POD.38

Sahker, E., Furukawa, T. A., Luo, Y., Ferreira, M. L., Okazaki, K., Chevance, A., Markham, S., Ede, R., Leucht, S., Cipriani, A., & Salanti, G. (2024). Estimating the smallest worthwhile difference of antidepressants: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Mental Health, 27(1), e300919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjment-2023-300919

Selalmazidou, A.-M., & Bschor, T. (2023). Depression: Niedrigschwellige Kardinalmaßnahmen als Basis jeder Behandlung. Fortschritte der Neurologie · Psychiatrie, 91(12), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2169-2120

Serretti, A., & Chiesa, A. (2009). Treatment-Emergent Sexual Dysfunction Related to Antidepressants: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 29(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f

Sharma, T., Guski, L. S., Freund, N., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (2016). Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: Systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i65

Soumerai, S. B., Koppel, R., Naci, H., Madden, J. M., Fry, A., Halbisen, A., Angeles, J., Koppel, J., Rubin, R., & Lu, C. Y. (2024). Intended And Unintended Outcomes After FDA Pediatric Antidepressant Warnings: A Systematic Review. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 43(10), 1360–1369. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00263

Spielmans, G. I., Spence-Sing, T., & Parry, P. (2020). Duty to Warn: Antidepressant Black Box Suicidality Warning Is Empirically Justified. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00018

Stone, M. B. (2014). The FDA Warning on Antidepressants and Suicidality—Why the Controversy? New England Journal of Medicine, 371(18), 1668–1671. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1411138

Stone, M. B. (2018). In Search of a Pony: Sources, Methods, Outcomes, and Motivated Reasoning. Medical Care, 56(5), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000895

Stone, M. B., Laughren, T. P., Jones, M. L., Levenson, M., Holland, P. C., Hughes, A., Hammad, T. A., Temple, R., & Rochester, G. (2009). Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: Analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ, 339, 1–10.

Stone, M. B., Yaseen, Z. S., Miller, B. J., Richardville, K., Kalaria, S. N., & Kirsch, I. (2022). Response to acute monotherapy for major depressive disorder in randomized, placebo controlled trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration: Individual participant data analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 378, e067606. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-067606

Strawn, J. R., Moldauer, L., Hahn, R. D., Wise, A., Bertzos, K., Eisenberg, B., Greenberg, E., Liu, C., Gopalkrishnan, M., McVoy, M., & Knutson, J. A. (2023). A Multicenter Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Escitalopram in Children and Adolescents with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 33(3), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2023.0004

Strawn, J. R., & Walkup, J. T. (2025). Fact Versus Fear: Antidepressants in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 45(5), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0000000000002054

The White House. (2025). The MAHA Report. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/MAHA-Report-The-White-House.pdf

Türkmen, C., Machunze, N., Lee, A. M., Bougelet, E., Ludin, N. M., de Cates, A. N., Vollstädt-Klein, S., Bach, P., Kiefer, F., Burdzovic Andreas, J., Kamphuis, J., Schoevers, R. A., Emslie, G. J., Hetrick, S. E., Viechtbauer, W., & van Dalfsen, J. H. (2025). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: The Association Between Newer-Generation Antidepressants and Insomnia in Children and Adolescents With Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, S0890-8567(25)00013-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2025.01.006

Vitiello, B., Silva, S. G., Rohde, P., Kratochvil, C. J., Kennard, B. D., Reinecke, M. A., Mayes, T. L., Posner, K., May, D. E., & March, J. S. (2009). Suicidal events in the Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 70(5), 741–747.

Whiteford, H. A., Harris, M. G., McKeon, G., Baxter, A., Pennell, C., Barendregt, J. J., & Wang, J. (2013). Estimating remission from untreated major depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 43(08), 1569–1585. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001717

Are you able to convey the onceot of and differentiate between quantitative and qualitative risks in the thoughts be oming and and not becoming words? The aggregating of data is occurring more rapidly, perhaps not better if there is,a rush to publish. How to keep the discovery curious in realizing a heaing moment?

Report comment

I don’t know. Seems all are barking up the wrong tree. The debate for the idea of chemical intervention seems the only debate and in my view there is a gigantic gap, hole rip in the universe with children in all parts of the globe. We have wars and genocides. The Amazon River continues to be in danger. Many countries including my own are becoming authoritarian. I think the reason to the suicidality is clear. Every aware or even underground awareness that children and some adults have is that in our now it is a five alarm fire. So folks are depressed. The psychiatric community how ever it is composed is living in a walled area if they can’t not feel this. Even the media folks are giving ini lectures on how to cope. And it’s not always taking a pill. So many alternative therapies!!!!!

Rorarach who used the inkblot experienced living as a staff member in a Swiss or Australian hospital where the pts and staff intermixed all the time. The whole concept of milieu has been jettisoned and the places that do have a kind of still don’t hit the mark. If there were ever any really good places. It seems always hit and miss and random luck or random bad luck.

One has to be listened to as in Virginia Axline’s Dibs in Search of Self. Not perfect and hidebound but I have seen her reflective listening work.

I don’t think many of these folks have ever read the book and are they ignorant of community and a framework that helps folks and also acknowledge the truth? Scary times are scary times. Folks have always used substances to cope but as a medical professional one would hope true help and this debate just seems so yucky right now.

Report comment

You hit the nail on the head. I live in Australia and am being persecuted for political reasons which is covered up by a fraudulent schizophrenia diagnosis and involuntary long term drugging. Most people with this same diagnosis are being persecuted although some psychiatrists are keen to just diagnose anyone with this fake illness regardless of whether theyre actually victims of persecution or not. And the rest of “mental illness” is also the result of living under capitalist-imperialism. This regime breaks people and creates psychological, spiritual, emotional etc dysfunction

Report comment

This article is written in the vaunted academic tradition, with an extremely conservative approach to calling out the lies and deceit behind the continued widespread use of harmful drugs to treat “mental illness.”

I believe that the time and need for conservatively-written papers on this subject has come to an end. We face the full takeover of this planet by psych-influenced corporate powers who will turn it into a police state given the opportunity. There are people still alive who would prefer spiritual freedom and the recognition of Spirit in the sciences. There are, in fact, many. “MAHA” helped Trump get elected; even though Trump now seems to be falling for the same pro-police-state arguments that all of his predecessors have fallen for.

This is not just a matter of propaganda being used to support vested interests. We are at an important point in this chapter of the history of Earth (and perhaps the universe). Scientific evidence for Spirit is now about 100 years old, and growing every day. We must topple the power structures (to use a phrase from Critical Theory) that continue to deny Spirit in the face of stronger and stronger evidence for its existence. And psychiatry – claiming to be “healers if the soul” – cannot be allowed to escape its responsibility to either finally get this right, or close up shop and leave Earth.

Any REAL discipline of social psychology that may emerge has a tremendous amount of work to do. Indeed, the odds of failure mount every day. So let’s not mince words. This is very much like a war. Many have called it such. We cannot afford to act as though it’s all business as usual. That is THEIR tactic. Don’t let them succeed with it!

Report comment

There’s sometimes no need to quote a study.

Just by knowing who pays the psychiatrists doing the study, you can infer if they will be pro or against medication. Just say, for instance “in a study paied for by Eli Lilly” and you know that the conclusions will be in favor of the Eli Lilly antidepressants.

Report comment

I was one of the first teenagers given SSRIs when they came out and individuals who question the connection between SSRIs and suicide have a fundamental misunderstanding of the effects they have on people who take them. My experience is that they worked by numbing my fear response in stressful situations. When I was depressed and anxious this could be beneficial in that it allowed me to confront my problems and change my life circumstances without the debilitating fear I would otherwise experience.

That said, suppressing someone’s fear can also have a dark side. People who aren’t fearful are more likely to act impulsively and do things they otherwise would not do. If someone is already suicidal and an SSRI suddenly takes away their fear of consequences they are then more likely to follow through with act. Someone who is not fearful is simply more likely to pull the trigger if given the opportunity.

It terrifies me that it has been nearly 40 years since Prozac was first approved and the people prescribing SSRIs still don’t understand the fundamental physiology of how they change a person’s behavior.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Upton Sinclair

Report comment

That is my observation as well. SSRIs seem to suppress inhibitions in many people. A friend of mine called it “Zolofting.” Kind of a “who gives a fuck” attitude, she said.

If you’re inhibiting telling your mom that you won’t come to Sunday dinners to be verbally abused any longer, that probably will be seen as a success. But if you’re inhibiting a desire to kill yourself because your kids will be devastated, deciding you don’t care that much is not where you want to go!

Report comment

Thanks for sharing your experience! Suppressing fear associated with suicidality has not been discussed in the literature, AFAIK.

Report comment

Evidence-based medicine…. Probably true evidence-based medicine… It includes studies conducted in the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s. But of course, it only includes pre- and post-drug psychiatric drug trials (studies). There are also studies that—in fact, they trash—studies that portray psychiatric drug studies as positive. While outdated, these may be valid. Peter Breggin has discussed these studies in depth. And he has refuted most – if not all – of these studies.

Today, evidence-based medicine—especially psychiatric drug trials—is deeply misleading. It’s incredibly false and inaccurate. Because mainstream psychiatry and pharmaceutical companies… continue to support them unabated. And they appear to be funding these studies to continue their psychiatric atrocities and genocides around the world.

***

One last word… I have something interesting to tell you. The World Health Organization is said to have made a very important decision that will lead to the “forced vaccination of all people.” The WHO is trying to reduce the human population through vaccines. Mainstream psychiatry and psychiatric pharmaceutical companies… seem to be collaborating with the WHO.

One day, the police might come to your home and take you and your family, your spouse, and your children, to be ‘forced to vaccinate.’ Because that’s what the WHO guidelines include. Forced vaccination. The US has withdrawn from the WHO, but the ‘WHO guidelines’ still apply in US ‘health units.’ This could indicate that forced vaccinations could occur in the US. In the rest of the world—especially in all countries except China and Russia—it’s seen as if “a population genocide is about to occur.” Where do China and Russia fit into this? In the rest of the world—especially in all countries except China and Russia—it appears that “a population genocide is imminent.” What kind of secret work might be taking place between China, Russia, and the WHO? I can’t quite figure that out.

As for the connection between this genocide and psychiatric drugs… It’s likely that… psychiatric drugs are closely linked to this ‘forced vaccination decision’… as is well known, hidden in the WHO agreements of mainstream psychiatry and psychiatric pharmaceutical companies. If the US population cannot be reduced through vaccinations… this can be achieved through psychiatric drugs. This could lead to an incredible increase in the number of mental illnesses in the US. We may need to be vigilant and, as societies, achieve ‘inter-societal unity’ and initiate ‘inter-societal struggles.’

I thought this was a great article. Thank you, Martin Plöderl. Best regards.

With my best wishes. 🙂 Y.E. Researcher and blog writer (Blogger)

Report comment

Something cannot cause itself.

Depression, which has as a diagnostic criterion suicidality, cannot cause suicidality.

Report comment

So to sum up: Researchers lie, cheat and misrepresent the data to artificially support their favored intervention, namely drugs. As to WHY so many researchers seem to favor drugs in spite of contrary evidence, we can only speculate… $$$$$?

Report comment

Psychiatry is not a “medical specialty”. It uses repurposed drugs with the exception of lithium. It treats and manages symptoms of ills that it defines as “disturbances” and/or “impairments”. So called “new meds” are simply copycats of older off patent drugs.

If psychiatry was judged by long termed outcomes no one would pay for their “services” since their evidenced based outcomes are very poor! Research shows no targets for real treatments. A scam.

Report comment

“Here I agree with them, because the increased relative risk for suicidality found in clinical trials is small and this supports the view that most suicides are independent of harmful effects of the drugs.”

A recent study found that depressed people who died by suicide with violent means

“their genomic profile of risk was relatively low for their diagnosed illness as well as for suicide attempt, and relatively high for IQ: they were more similar to the neurotypical group than to other patients”.

They concluded that their outcome “may be less dependent on genetic risk for psychiatric disorders and be associated with an alteration of purinergic signaling and mitochondrial metabolism”.

In other words, a metabolic condition, not “mental illness”.

Lisa Pan also found the same alteration in purinergic signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction in suicidal patients as well as Cerebral Folate Defficiency, high homocysteine, low Vit D, lipid abnormalities, reductive stress, all of which can be caused by SSRIs.

Report comment