A new article in Incarceration argues that involuntary community treatment can operate as a dispersed carceral system.

Sociologist Panos Karanikolas maps what he calls the “psychiatric circuit,” showing how Community Treatment Orders (CTOs) couple medication mandates with surveillance, coerced mobility, and routine police involvement.

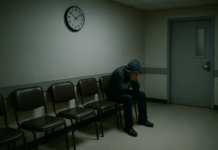

Drawing on interviews in Victoria, Australia, the paper describes a pattern in which people live outside hospitals yet remain governed through legal orders, check-ins, home visits, and the ever-present threat of recall to inpatient care.

“Psychiatric circuits’ is my offering to abolitionist knowledge and discourse that seeks to understand and resist the full spectrum [of] carceral violence, including that which occurs within systems that exist ostensibly to deliver treatment and care,” Karanikolas writes.

The circuit, Karanikolas writes, “plays a pivotal role in the wider carceral landscape and acts as a threshold to the criminalisation and policing of people deemed ‘mentally ill’.”

What looks like care, he argues, relies on “psychopharmaceuticals to sedate,” “surveillance and coerced mobility across a multiplicity of sites,” and “transcarceral” transfers into police and family-policing systems.

CTOs, also called “assisted outpatient treatment” or “mandatory outpatient committal,” authorize forced psychotropic drug use (most often via long-acting depot injections) while a person lives in the community. They are now common in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, and are often presented as “less restrictive” than hospital detention. The article challenges that premise, arguing that CTOs embed carceral logics in ordinary settings and “enlist patients into both punitive movement and immobilisation.”

The analysis lands at a politically charged moment. In July 2025, the White House issued an executive order urging expanded civil commitment as a homelessness response, a step critics say conflates poverty and disability and risks more coercive psychiatry in the community. Several legal and policy groups warned the order would criminalize homelessness and encourage forced treatment in the name of public safety.