On July 21, the FDA convened a panel on antidepressants in pregnancy, with a focus on possible harms to the fetus from exposure to the drugs. Several members of the panel were well known to readers of Mad in America, as it included Adam Urato, David Healy, Joanna Moncrieff, and Josef Witt-Doering. Urato, an OB-GYN, has presented a course on Mad in America Continuing Education on this topic.

Three other panel members, Anick Bérard, Jay Gingrich, and Michael Levin, had conducted research relevant to this subject, and together the panel told of how fetal exposure to SSRIs and SNRIs altered fetal brain development, which Urato and others pointed to as the most alarming concern. The panel spoke too of animal and human research that told of possible adverse pregnancy outcomes and increased risk for psychiatric disorders related to that intrauterine exposure. There were non-drug modalities for treating depression that could be used during pregnancy, the panel noted, and parents were not being properly warned of the risks associated with fetal exposure to SSRIs and SNRIs.

“Over the years, I’ve seen more and more medication use in pregnancy, and I think that pregnant women and the public aren’t being properly informed on this issue, particularly with SSRI antidepressants,” Urato said. “Patients regularly tell me that essentially the only counseling they received is that SSRIs don’t affect the baby or cause complications. This is simply not accurate or adequate.”

However, their brief presentations, and their plea for informed consent, did not sit well with medical trade associations. The American Psychiatric Association, the National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine all issued statements denouncing the panel as biased and misinformed, declaring that the evidence showed that SSRIs and SNRIs were an effective and safe treatment for prenatal depression, and that the real concern was “untreated depression.” Major media echoed this “expert consensus” in their reporting on the panel.

This dichotomy, between the FDA panel and the medical “experts,” is clearly an important one for society to resolve. An estimated 400,000 children are born each year in the United States who have had fetal exposure to antidepressants, Gingrich said, and if there is good evidence that this exposure alters fetal brain development, such that its cellular organization and global function is altered, this is surely a practice that deserves public scrutiny, and an honest account of the evidence that exists in the scientific literature.

The review will also provide an opportunity to assess whether the American Psychiatric Association—and in this case the other medical organizations that slammed the panel—is a reliable narrator of its own scientific literature, or whether its public pronouncements invariably serve its guild interests, rather than the public’s right to informed consent.

A Review of the Evidence

The role of serotonin in fetal development

As anyone who has held a newborn can attest, there is a reason that the birth is described as the “miracle of life,” for the nine-month journey from newly fertilized egg to newborn boggles the mind. You know that it is a biological process shaped by the evolution of life over the span of three to four billion years, reaching its apotheosis with organization of the human brain. The first fertilized cell divides over and over again, with the cells differentiating into different types and migrating into their proper place in brain and body, and it is impossible to imagine how the genetic code in that first fertilized cell orchestrates this exquisite creation of a human being.

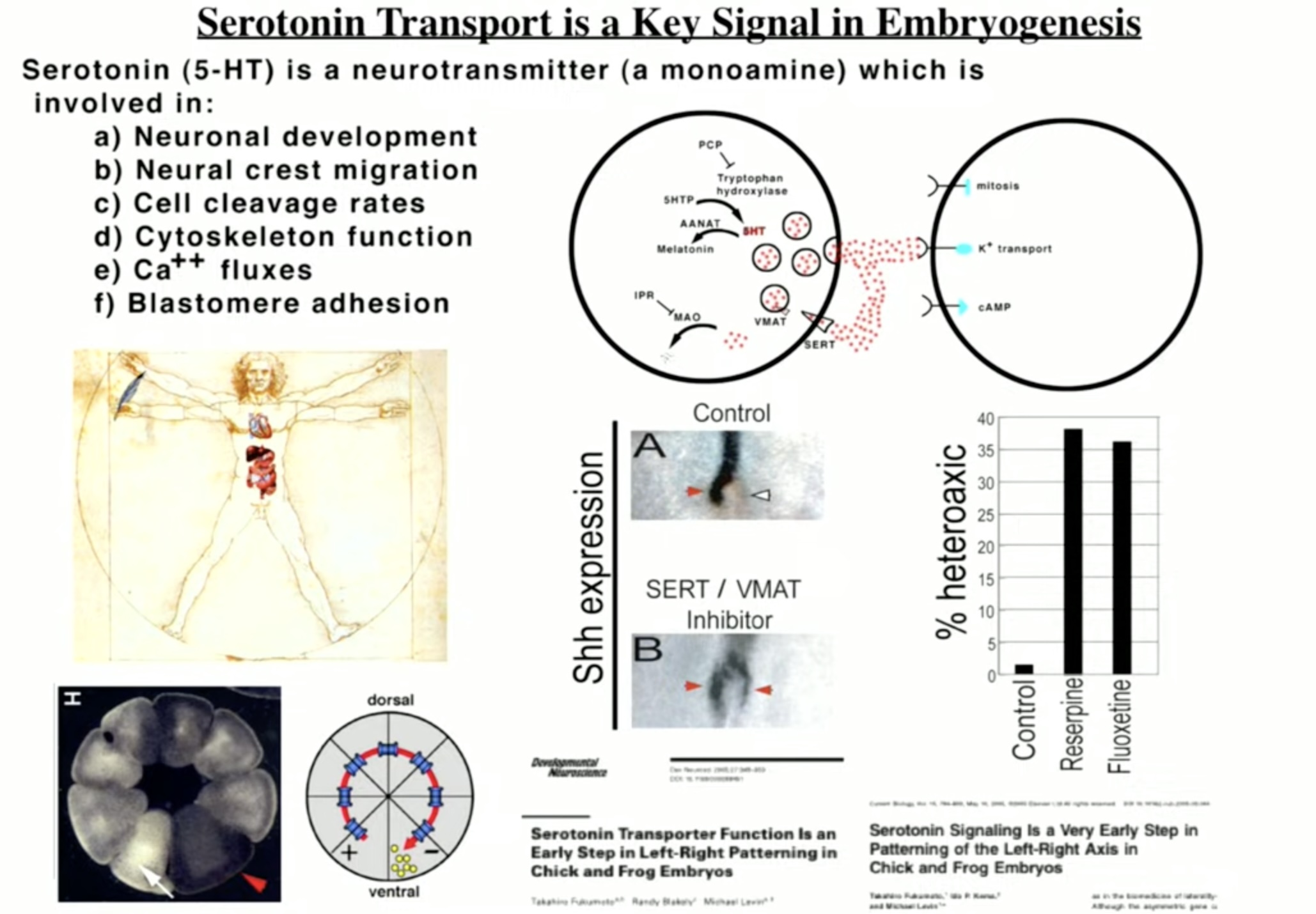

Now serotonin (5-HT) is an ancient molecule, having appeared early in the evolution of life on earth, and it could be described as a workhorse molecule in the animal kingdom. In humans, the molecule appears within five weeks of conception, and researchers have discovered it plays a critical role in guiding the cellular organization of the fetal brain.

Michael Levin, a professor of biology at Tufts University, who has spent decades studying the role of serotonin in fetal development, told of this process at the FDA hearing. “Evolution exploited serotonin as a very significant and powerful signaling modality. It affects, of course, the development of the nervous system, but also neural crest migration, cell division, or the rate of cell cleavage, and mitosis . . . it has lots of effects in embryogenesis.”

Levin’s work is part of a larger body of research on the role of serotonin in fetal brain development. A 2012 review of this literature summed up serotonin’s role in this way:

“5-HT is a phylogenetically ancient neurotransmitter widely distributed throughout the brain. 5-HT plays two key roles: during early developmental periods, 5-HT acts as a growth factor, regulating the development of its own and related neural systems. In its role as a trophic factor, 5-HT regulates diverse and developmentally critical processes, such as cell division, differentiation, migration, myelination, synaptogenesis, and dendritic pruning.”

SSRIs, of course, alter serotonergic function, and research has shown that these drugs, when used by the mothers, cross the placental membrane and into the fetus’s circulatory system (via the umbilical cord). The serotonergic drugs can also be found in the amniotic fluid, which the fetus swallows.

“My message is very simple,” Levin concluded. “Serotonin is an important early embryonic signal, and manipulating its use by cells with SSRIs is very, very likely to cause certain kinds of defects.”

Animal studies

With understanding of serotonin’s role in fetal development in mind, researchers began conducting studies in rats and mice more than 20 years ago to assess the impact of SSRIs during pregnancy. These studies can isolate the causal effects of fetal exposure to SSRIs, as these small mammals are not suffering from depression, and thus there is no confounding factor of “mental illness” altering fetal development.

This animal research has shown fetal exposure to SSRIs leads to altered brain development, numerous risks to fetal health, and deficits in behavior after birth. The rodent studies have found that perinatal SSRI exposure disrupts thalamocortical organization, reduced dorsal raphe neuronal firing, reduced arborization of 5-HT neurons, and altered limbic and cortical circuit functioning. At birth, fetal SSRI exposure in rodents is associated with low birth weight, persistent pulmonary hypertension, increased risk of cardiomyopathy, and increased postnatal morality. After birth, such exposure is associated with delayed motor development, reduced pain sensitivity, disrupted juvenile play, fear of new things, and to a “higher vulnerability” of affective disorders (such as anhedonia-like behavior.)

Gingrich and his colleagues at Columbia University published evidence of this “higher vulnerability” to affective disorders in 2004, when they reported that mice exposed prenatally to fluoxetine had “abnormal emotional behavior” as adults. As an article in Science about their work explained, the adult mice “showed reduced exploratory behavior in a maze test. They also took longer to start eating when placed in a novel setting and were slower to try to escape a part of the cage that gave them mild foot shocks. All these behaviors are regarded as signs of anxiety and depression in animals.”

As a later review explained, this maladaptive behavior could be directly tied to serotonin’s role in fetal brain development. Serotonin is “central to the development of two key stress response systems—the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and the locu coeruleus-norepinephrine systems [and] alterations in HPA function often characterize anxiety and depressive disorders,” the review stated. As stated, “given (serotonin’s) broad function in shaping human neurobehavior, it is not inconceivable that altering 5-HT levels during developmentally sensitive periods would have critical implications for subsequent behavior and mental health across the life span.”

In a 2007 paper titled “Developmental Side Effects of SSRIs: Lessons Learned from Animal Studies,” University of Virginia researchers neatly summed up the scientific understanding that had emerged from animal research:

“In this review, we have presented the major steps of serotonin signaling: serotonin synthesis and packaging, reuptake, and degradation. We have stressed the effects that each of these processes has on the regulation of serotonin levels and the developing brain. Animal studies have shown the importance of serotonin signaling in modulating neuronal circuitry, 5HT receptor level, and behavior. Regardless of the method employed, increased extracellular serotonin levels during the perinatal period can cause subtle changes in brain circuitry and maladaptive behaviors, such as increased anxiety, aggression, or depression, that are maintained into adulthood . . . Serotonin signaling is highly conserved, and therefore many of these animal model findings are relevant to humans.”

Human Studies

There are four aspects of research on the impact of fetal exposure to SSRIs and SNRIs in humans. First, does this exposure alter brain development? Second, does it increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes? Third, does it expose the newborn to withdrawal symptoms, and thus impair post-natal health? Fourth, does it increase a risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders?

Impact on brain development

There are a fair number of published studies that tell of how in utero exposure to SSRIs alters brain development in humans. Here is a sampling of such findings:

- In 2016, Finnish researchers conducted neurophysiological tests on 84 newborns (22 with SSRI intrauterine exposure and 62 controls), and found lower levels of “global integration,” “interhemispheric connectivity,” and “local cross frequency integration” in the SSRI-exposed group. These changes, the researchers noted, are associated with less-organized communication between the brain’s hemispheres and are comparable to the effects found in animal studies, with these changes outlasting the known period of immediate withdrawal common to newborns.

They concluded: “This is the first study to show that prenatal SRI exposure in humans can affect the newborn cortical function beyond the acute withdrawal period . . . Our detailed, quantitative, computational EEG analysis indicated SRI-related effects in both focal and global brain activity.”

- In a 2018 study, Gingrich and colleagues used MRIs to study brain volume in 98 infants. Sixteen of the 98 had intrauterine exposure to SSRIs, 21 had “untreated maternal depression exposure,” and there were 61 controls. This design enabled the researcher to assess whether any brain abnormalities in the SSRI exposed group were absent in those born to mothers with depression. The researchers found that in the SSRI-exposed infants, “significant gray matter volume expansion was noted in the amygdala and insula, as well as an increase in white matter structural connectivity between these same region” as compared to infants “exposed to untreated prenatal maternal depression and healthy controls.”

As these abnormalities were only seen in SSRI-exposed infants, the researchers concluded that “in line with prior animal studies, these multimodal brain imaging findings suggest that prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure has a significant association with fetal brain development.”

- In 2023, researchers in the Netherlands used MRIs to study brain volumes in 3198 children, with three assessments done between ages 7 and 15. With healthy controls serving as a reference, they measured brain volumes in youth with fetal exposure to SSRIs, and in youth with fetal exposure to “untreated” depression.” This comparison enabled the researchers to determine whether any differences in brain volume, compared to the healthy controls, were due to the drug or to the “disease.”

They found a “persistent association between prenatal SSRI exposure and less cortical volumes across the 10-year follow-up period, including in the superior frontal cortex, medial orbitofrontal cortex, Para hippocampal gyrus, rostral anterior cingulate cortex, and posterior cingulate . . . prenatal SSRI exposure was consistently associated with lower volume, ranging from 5% to 10% in the frontal, cingulate, and temporal cortex across ages.”

Although children in the “untreated depression” group had slightly smaller white matter brain volumes than the healthy controls, the reduction was less than one-fourth seen in the SSRI-exposed children, and they also did not show reduced volumes in other areas of the brain.

Together, these three studies told of how fetal exposure to SSRIs is associated with altered volumes in different areas of the brain and diminished the communication between different areas of the brain (and thus cortical function).

Ultrasound studies have also found that SSRI exposure alters the behavior of the fetus. In one such study, fetuses exposed to a standard SSRI dose show “significantly increased motor activity” throughout the second trimester. During the third trimester, they exhibit “disrupted emergence of non-rapid eye movement (non-REM; quiet) sleep, characterized by continual bodily activity and, thus, poor inhibitory motor control during this sleep state.”

The researchers compared this SSRI-exposed fetal behavior to both normal controls and to untreated depression, and this abnormal fetal behavior was seen only in the SSRI-exposed group. “Bodily activity at high rate during non-REM sleep in SSRI-exposed fetuses is an abnormal phenomenon, but its significance for postnatal development is unclear,” the researchers concluded.

Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

With the animal studies showing an increased risk for adverse outcomes in pregnancy, such as miscarriages, pre-term birth, low birth weight, congenital malformations, and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, the first wave of studies on “antidepressants in pregnancy” focused on these concerns. This research produced an abundance of findings that the risk of such adverse events is elevated with fetal exposure to SSRIs in comparison to health controls.

Bérard reviewed some of these findings at the FDA hearing, telling of how SSRI use during pregnancy was associated with a 56% increased risk of miscarriage, a doubling of cardiac malformations, and 20% to 50% increases risk for premature birth and low birth weight.

However, the question remains whether these adverse pregnancy risks are raised in comparison to untreated depression in pregnancy, and while there are a number of studies that have sought, in one manner or another, to account for this possible cofounder, the untangling of these two factors—antidepressant use and untreated depression—could be said to be incomplete, worthy of further research.

Nevertheless, a 2022 review of the literature on this subject concluded that SSRI use in pregnancy, compared to untreated maternal depression in pregnancy, is associated with a “small increase in risk of pre-eclampsia, post-partum hemorrhage, preterm delivery, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, and neonatal intensive care unit admissions.”

In other words, treating maternal depression during pregnancy with SSRIs doesn’t reduce the risk of these adverse events, but rather increases the risk of such events, even if to a small degree. As such, at least by these measures, the treatment of maternal depression with antidepressants is not just ineffective related to these adverse effects but adds a dollop of harm.

A study by Kaiser Permanente of Northern California of 82,170 pregnant women quantified this extra dollop of harm. Mothers with untreated depression had a 41% increased risk of a pre-term delivery. However, if the depression was treated with counseling, this risk was reduced by 18%, whereas treatment with an antidepressant increased it by 31%. The researchers concluded that “use of antidepressants may add additional risk of preterm delivery, independent of the underlying depression.”

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

Once the umbilical cord is cut, a newborn with intrauterine exposure to an SSRI or SNRI is, in essence, “cold turkeyed” off the drug. The newborn is exposed to drug-withdrawal effects, which in the literature is referred to as “neonatal abstinence syndrome” (NAS). This, of course, is not an adverse effect that can be attributed to “untreated depression,” but rather is a harm that is directly tied to the mother’s antidepressant during pregnancy.

NAS symptoms may appear within hours of birth and persist for as long as a month. Researchers have published an extensive list of NAS symptoms, which includes jitteriness, poor muscle tone, weak cry, abnormal crying, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia tachycardia, low Apgar score, seizure, abnormal behavior, sleep abnormalities, poor feeding, vomiting, uncoordinated sucking, lethargy, and increased reflexes. In a study that plumbed the World Health Organization’s database for adverse drug effects, researchers classified 80% of the reported NAS symptoms as “serious.”

NAS is said to occur in 30% of newborns exposed to SSRIs in utero. However, a small study of 76 mothers taking antidepressants found that 63% of the newborns had signs of central nervous system problems and 40% had signs of respiratory problems, suggesting that many SSRI newborns have milder difficulties that aren’t chalked up to NAS.

The long-term outcomes of infants diagnosed with NAS, compared to infants with prenatal exposure to SSRIs who are not diagnosed with such withdrawal symptoms, has not been fleshed out. However, one study of 82 children that made this comparison found that while both groups had similar cognitive abilities and developmental scores at ages two and six, the NAS group had a three-fold increased risk of social behavioral abnormalities at those two ages, suggesting that severe neonatal withdrawal symptom may be a marker for greater impairments later on.

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The rodent studies told of how fetal exposure to SSRIs regularly led to maladaptive adult rodents, and studies of children exposed in utero to SSRIs, in comparison with healthy controls, have elevated risks of neurodevelopmental disorders. They show delays in developing developmental milestones and are at increased risk of being diagnosed with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, and affective disorders. However, maternal depression is known to confer such developmental risks on children, and thus researchers, as this line of research has been pursued, have sought to account for this confounding factor of “untreated maternal depression.”

These studies have produced inconsistent results. There are a fair number of studies, often involving large datasets, that have sought to account for this confounding factor of untreated maternal depression and found that a heightened risk of a neurodevelopmental disorder remains with prenatal exposure to SSRIs. However, a handful of others have reported that after adjusting for confounding factors, the excess risk disappears, or at least mostly disappears, which is why the literature is regularly said to be “inconsistent” regarding these risks.

Here is a sampling of the more prominent studies that have sought to isolate this risk:

- In a 2011 study, researchers at Kaiser Permanente in Northern California reported a two-fold increased risk of autism spectrum disorders in children born to mothers who used SSRIs in the 12 months prior to delivery. No increase in risk was found for mothers who had a history of mental health treatment who did not take SSRIs while pregnant.

- In a 2013 study of children born after 1995 and who lived in Stockholm County, Sweden, from 2001 to 2007, researchers compared SSRI-exposed youth and youth exposed to untreated maternal depression to a healthy control group. The SSRI-exposed youth were 5.58 times more likely than the control group to have been diagnosed with “autism spectrum disorder without intellectual disability,” while the increased risk for the untreated depression cohort was only 1.3 times. In other words, the risk was more than four times greater for the SSRI-exposed cohort than the untreated depression offspring.

- In a 2015 study of all children born in Quebec from 1998 to 2009, Bérard and colleagues found that the risk of developing autism spectrum disorder was 1.75 times greater for those with fetal exposure to SSRIs, with this risk persisting “even after taking into account maternal history of depression exposed infants.”

- In a 2015 study of more than 10,000 children born in New England hospitals, the risk of an ADHD diagnosis up through the age of 10 was nearly double for those with prenatal exposure to antidepressants, “even after adjustment for maternal depression.” However, the risk of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, while higher for the prenatal exposure group compared to healthy controls, disappeared after adjustments for maternal major depression and sociodemographic factors.

- In a 2016 study of all children born in Finland from 1996 to 2000, fetal exposure to SSRIs (N= 15,596) led to a 37% increased risk of speech/language disorders compared to children whose mothers had a psychiatric diagnosis but did not take SSRI antidepressants (N=9,537). The study assessed children up to 14 years of age.

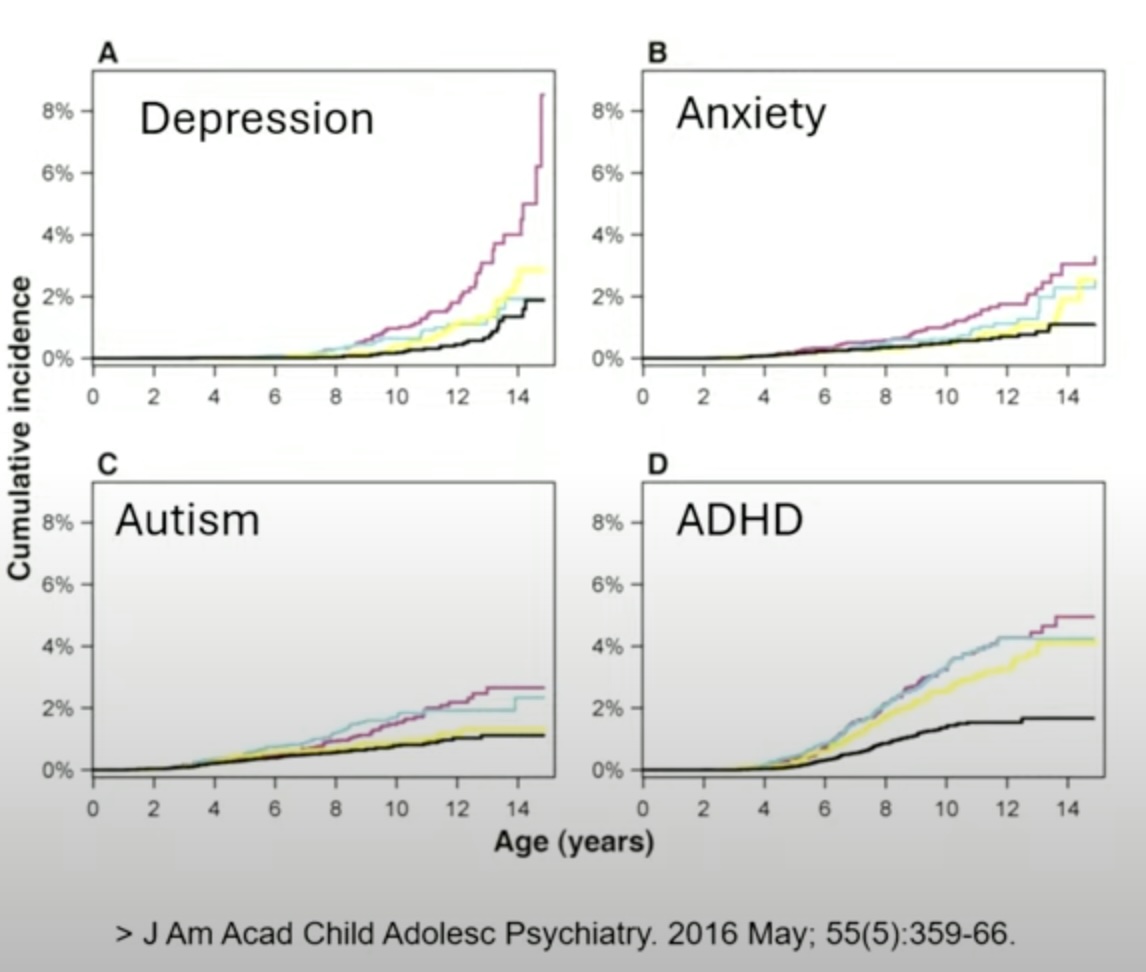

- In a second study of all Finnish children born from 1996 to 2010, Gingrich and colleagues found that by age 15, 8.2% of those exposed in utero to an SSRI had a diagnosis of depression, compared to 2% for children of mothers with a mood disorder who didn’t take medication during pregnancy, with this increase in diagnoses in depression mostly emerging in youth 12 and older. However, there were no significant differences in diagnoses of ADHD, autism spectrum disorder and anxiety disorders.

Here is a graphic from this study, which Gingrich presented at the FDA hearing, and shows the sharp increase in depression for the SSRI group (the maroon line.) The rates of anxiety, autism and ADHD for the SSRI group were also higher at age 14, but not significantly so.

- A 2017 Danish study of nearly one million children born from 1998 to 2012, who were followed for a maximum of 16 years, divided mothers into four groups related to fetal exposure to antidepressants, and then assessed the percentage of their children who had a psychiatric diagnosis. The rate was 8% for the never-exposed group; 11.5% for those whose mothers took an antidepressant in the two years before pregnancy but then discontinued before becoming pregnant (discontinuation group); 13.6% for those who used an antidepressant in the two years prior to becoming pregnant and continued using the during pregnancy (continuation group); and 14.5% for those who hadn’t used antidepressants before pregnancy but were “new users” of the drugs during pregnancy.

The Danish researchers also assessed different rates of specific psychiatric diagnoses, comparing the discontinuation and continuation cohorts, and found that the rate of mood disorders was nearly three times higher in the latter group, which was a finding, the authors noted, predicted by animal studies.

“The rationale for these results could be the fact that serotonin acts as a trophic factor, particularly in those brain systems that modulate emotional function,” they wrote. “Serotonin has an influence on several developmental processes such as neuronal differentiation, migration, and synaptogenesis. Consequently, early manipulation of the serotonergic system could contribute to emotional disorders in offspring.”

- In a 2019 study of 4,788 U.S. children, the adjusted risk of being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder among those with fetal exposure to antidepressants was double that of children born to mothers without a psychiatric diagnosis and no use of antidepressants (adjusted OR 2.05). This adjusted risk was slightly less for children in the “unmedicated maternal depression” group (adjusted OR 1.81), meaning that the exposed children had a 14% greater risk of being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder than those exposed to unmedicated maternal depression. However, the researchers concluded that this difference was not significant, and that nearly all of the excess risk could be attributed to maternal psychiatric illness, regardless of whether it was treated in pregnancy.

- In a 2020 systematic review of 34 studies, researchers determined that there were “statistically significant associations between in utero exposure to antidepressants and a wide range of physical, neurodevelopmental and psychiatric outcomes.” However, after adjusting for confounders, they concluded that most of these negative outcomes “in large part, seem to be driven by the underlying maternal disorder.” They did find an increased risk of affective disorders that persisted even after adjusting for confounding factors.

- In a 2020 study of children born to women who had a mood or anxiety diagnosis in the 90 days before conception, at age five those with fetal exposure to SSRIs or SNRIs were 40% more likely to show developmental delays in language and cognition than those unexposed to the antidepressants.

- In a 2023 study of 1,489 Quebec children, prenatal exposure to antidepressants was related to impaired fine motor and gross motor development at age two, and this negative association remained “after adjusting for maternal prenatal distress.”

- In a 2025 study, Gingrich and colleagues reported that in both mice and humans, prenatal exposure to SSRIs led to a hyperactive amygdala, and that both were more fearful and depressed as adolescents. Maternal depression did not explain the effect.

In many ways, the 2025 study was the culmination of two decades of research by Gingrich and colleagues at Columbia University. They had documented alterations in brain structure and function in both mice and humans exposed in utero to SSRIs, and had found that in both, maladaptive emotional behaviors emerged after puberty. “These findings demonstrate that increases in anxiety and fear-related behaviors as well as brain circuit activation following developmental SSRI exposure are conserved between mice and humans,” they wrote.

At the FDA hearing, Gingrich said that “these kids look pretty normal throughout early childhood, and then when they hit adolescence, their rates of depression really started to go up, which is what we see in our mouse studies.”

Weighing Risks versus Benefits

Assessing merits of a drug intervention requires weighing the risks versus the benefits. Yet, for the unborn child, fetal exposure to SSRIs only provides a tally of harms.

The most profound harm is that such exposure perturbs the normal development of the human brain. Quite apart from the specific potential harms reviewed here—adverse pregnancy outcomes, neonatal abstinence syndromes, and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric risks—that disruption in brain development alters the child’s very being, a loss that the above metrics couldn’t possibly measure. How does it change the child’s capacity for responding to the world, and to his or her own self? Will the child’s capacity for experiencing the world be diminished? Will the child have the same capacity for joy, the same curiosity, the same interest in new experiences as they would have had if their fetal brain had developed under the guiding hand of eons of evolution, rather than under the influence of a chemical that disrupted that process?

There is no way to know what that loss may be, but Urato, in his remarks at the FDA hearing, put it into a haunting perspective. “Never before in human history have we chemically altered developing babies like this, especially the developing fetal brain, and this is happening without any real public warning. That must end.”

Beyond that unmeasurable harm, the evidence reviewed here all tell of “harms.” Fetal exposure leads to at least 30% of newborns suffering withdrawal symptoms, which may persist for at least a month, and that suffering in their first month of life can’t be attributed to maternal depression. Fetal exposure to SSRIs also increases the risk, at least to a small degree, of adverse pregnancy, neurodevelopmental, and psychiatric outcomes, beyond the risk posed by maternal depression.

With nothing but harms to the unborn child to be tallied on the risk/benefit ledger, presumably the benefit from this practice comes in the form of relief of the mother’s depressive symptoms. However, there is no RCT data in studies of pregnant women that can attest to that “benefit.” Indeed, as MIA detailed in an earlier report on prenatal screening for depression, task forces set up in the UK, Canada and U.S. all struggled to find evidence that “screening plus treatment” provided any benefit to the mother. The UK Task Force, in a general review of antidepressants in pregnancy, concluded that “negative offspring outcomes were reported in all three systemic reviews,” and that “no study reported the benefits to women or their offspring from pharmacological interventions.”

Even when the focus is on treating the mother’s depression, it is difficult to find evidence that goes up on the benefit side of the ledger.

The Howl of Outrage

As noted at the start of this MIA Report, the American Psychiatric Association and other relevant medical organizations issued statements condemning the panel. Here are excerpts from four statements.

The America Psychiatric Association, July 25 letter to the FDA

“We are alarmed and concerned by the misinterpretations and unbalanced viewpoints shared by several of the panelists for the Expert Panel on Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Pregnancy panel on July 21st. This propagation of biased interpretations at a time when suicide is a leading cause of maternal death within the first postpartum year could seriously hinder maternal mental health care. The inaccurate interpretation of data, and the use of opinion, rather than the years of research on antidepressant medications, will exacerbate stigma and deter pregnant individuals from seeking necessary care.”

And: “The overall evidence suggests individuals can and should take SSRIs prior to and during pregnancy when they are clinically indicated for treatment. Moreover, recent meta-analyses have found no association between prenatal SSRI exposures and overall risk of birth defects . . . The dissemination of inaccurate and unbalanced information by a federally sanctioned public panel has the potential to cause harm. It can undermine public confidence in mental health treatment, exacerbate stigma, and deter pregnant individuals from seeking necessary mental health care.”

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, July 21 statement

“Today’s FDA panel on SSRIs and pregnancy was alarmingly unbalanced and did not adequately acknowledge the harms of untreated perinatal mood disorders in pregnancy. On a panel of 10 experts, only one spoke to the importance of SSRIs in pregnancy as a critical tool, among others, in preventing the potentially devastating effects of anxiety and depression when left untreated during pregnancy.”

And: “Robust evidence has shown that SSRIs are safe in pregnancy and that most do not increase the risk of birth defects. However, untreated depression in pregnancy can put our patients at risk for substance use, preterm birth, preeclampsia, limited engagement in medical care and self-care, low birth weight, impaired attachment with their infant, and even suicide . . . Unfortunately, the many outlandish and unfounded claims made by the panelists regarding SSRIs will only serve to incite fear and cause patients to come to false conclusions that could prevent them from getting the treatment they need.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, July 23 statement

“As experts in high-risk pregnancies, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) and its members are alarmed by the unsubstantiated and inaccurate claims made by FDA panelists concerning maternal depression and the use of SSRI antidepressants during pregnancy. SMFM strongly supports the use of SSRIs to treat depression during pregnancy.”

And: “Untreated or undertreated depression during pregnancy carries health risks, such as suicide, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and low birth weight . . . the available data consistently show that SSRI use during pregnancy is not associated with congenital anomalies, fetal growth problems, or long-term developmental problems.

The National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry, July 21 statement

“We are deeply concerned that the panel included speakers who presented misleading or stigmatizing information about psychiatric treatment during pregnancy, undermined the scientific consensus, and failed to appropriately center the well-being of pregnant individuals.”

And: “Claims of widespread harm were often based on studies that failed to adequately control for confounding by indication – that is the underlying mental health condition for which the medication was prescribed . . . more recent and methodologically rigorous studies that control for the presence and severity of depression have confirmed that earlier findings of harm no long hold up when appropriate control groups are used.”

Such was the response from the APA and other medical organizations. Now, one might think that science writers at major media would, in their coverage of the FDA panel, investigate whether it was true that SSRIs had been shown to disturb fetal brain development, and having discovered that this was so, questioned the American Psychiatric Association about the potential harm that would arise from that. Instead, in their reports, they jumped to validate the “expert consensus” criticisms of the panel.

Here is a sampling of such reports, including the headlines:

The LA Times. “FDA Panel on the Use of Antidepressants During Pregnancy Is Alarming Experts.”

“An FDA panel recently attacked SSRIs, a class of antidepressants that RFK Jr. has targeted in the past. Doctors say the panel—comprising mostly critics of antidepressant use—spread misinformation about the drugs’ use in pregnancy. The risks of not treating depression in pregnancy far outweigh those of SSRIs, healthcare providers said.

The NY Times (Op-ed). “The FDA’s Panel on Antidepressants During Pregnancy Was Alarmingly Biased.”

“Most of the panelists were clearly biased against antidepressant use . . . For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the panel was alarmingly unbalanced and did not adequately acknowledge the harms of untreated perinatal mood disorders in pregnancy.”

NBC News: “FDA Panel Promotes Misinformation About Antidepressants During Pregnancy, Psychiatrists Say.”

“A Food and Drug Administration panel discussing the use of antidepressants during pregnancy Monday largely amounted to misinformation or facts taken out of context, according to several psychiatrists who tuned into the meeting.”

NPR: “An FDA Panel Spread Misinformation about SSRI Use in Pregnancy, Alarming Doctors”

Studies that are well-controlled — in other words, those that compare pregnant women on SSRIs with pregnant women with mental health conditions not taking the drugs — do not find the risks highlighted by the FDA panel.

These reports, written with almost stenographic fidelity, serve to reify the “expert consensus” in the public mind.

There Will be No Informed Consent

As can be seen by the review of the literature in this report, the “talking points” put forth by the American Psychiatric Association and the other medical organizations are easily shown to be false.

To wit:

1) The panel members were misinformed.

Three of the panel members— Bérard, Gingrich, and Levin—were telling of their own research findings, which had been published in high-impact journals: Science, Nature, JAMA Pediatrics, and so forth. Healy, Moncrieff, and Urato all spoke about elements of this research that they are well versed in, and both Healy and Moncrieff have robust publishing records. Urato, meanwhile, knows the relevant research inside and out, as he has been speaking about the risk of fetal exposure to SSRIs for years.

2) The panel members were citing research that didn’t account for the confounding factor of untreated depression.

Bérard and Gingrich, and the larger research community, have been conducting studies for decades that sought to directly compare fetal outcomes in SSRI exposed youth to youth exposed to untreated maternal depression. You can see this in Bérard’s and Gingrich’s published studies. The risks of harm from fetal exposure to SSRIs is present in studies that compared SSRI exposure to healthy controls, and in studies that compared SSRI exposure to untreated maternal depression, and risks from both types of studies were presented at the hearing.

3) The risk of not treating depression in pregnancy far outweighs the risk of fetal exposure to SSRIs.

This is a claim plucked out of thin air. There is no evidence showing that fetal outcomes are superior in a “treated with SSRIs” cohort than in untreated depression. In addition, the panel members spoke of treating depression with non-drug alternatives.

4) Treating depression with SSRIs helps prevent the adverse outcomes associated with untreated depression.

This is another claim plucked out of thin air. There is no evidence that treating depression with SSRIs lowers the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with untreated depression. If anything, the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with SSRI exposure is higher than with untreated depression.

5) The available data consistently show that SSRI use during pregnancy is not associated with long-term developmental problems.

There are a number of studies comparing SSRI-exposed youth to untreated-depression youth, and, as noted in this MIA report, many have found higher risks for speech and languages delays, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and affective disorders. However, the literature is in fact inconsistent regarding these risks, although there appears to be rather consistent evidence regarding the increased risk of affective disorders in SSRI-exposed youth.

7) Antidepressants are an effective treatment for depression in pregnant women.

In her comments at the hearing, Joanna Moncrieff reviewed the research literature regarding the effectiveness of antidepressant in the general public, which shows that the drug-placebo difference in RCTs of SSRI antidepressants is so minimal that it isn’t clinically noticeable. Moreover, as was noted at the FDA hearing, there are no RCTs of antidepressants in pregnant women, and as the UK Task force determined, other types of studies of antidepressants in pregnant women failed to show a positive benefit.

In sum, the professional organizations misled the media, and the media in turn misled the public. And from a moral perspective, here is how to judge the statements from the professional organizations: they were putting their guild interests—e.g. protecting their prescribing practices and societal belief in the efficacy of antidepressants—ahead of their duty to provide informed consent.

And who is most harmed by this betrayal of the public’s right to know? Pregnant women, and their unborn children.