The first thing I’ll say about my experiences with healthcare while having an eating disorder is the fact that my eating disorder went undiagnosed for eight years. I think this fact speaks for itself. (And I am not some kind of rare exception.)

Since being formally diagnosed with an eating disorder nearly five years ago, I have had experiences within healthcare ranging from uncomfortable or unpleasant to downright traumatizing. Doctors have downplayed the severity of my eating disorder, questioned or denied its very existence, and sometimes even given me recommendations right in line with disordered eating behaviors—such as prescribing exercise when I was struggling with compulsive overexercise. Outpatient therapy with my so-called “care team” ended in ultimatums and abandonment. Very rarely (if ever) have experiences been positive, or even neutral.

In order to avoid the mainstream mental health system, I decided to take a “DIY” approach to recovery where I would manage the psychobehavioral side of things myself and find a doctor to support me through the physical side. But because of my negative experiences with “regular” doctors when it came to my ED, I made it my mission throughout my recovery to search for a doctor who specializes in EDs. However, every time I’ve scoured the internet for “eating disorder specialists” or “eating disorder doctors in my area”— changing the search input each time—all I would get were eating disorder therapists, eating disorder psychiatrists, and eating disorder registered dietitians. But no physicians (non-psychiatrists).

This confirmed my emerging hypothesis: Contrary to the problem with most mental healthcare, where the biomedical model dominates approaches to psychological suffering, the psychobehavioral side of ED healthcare disproportionately overshadows the medical side. As far as I can tell, it is safe to conclude that there is no real such thing as an eating disorder-specialized physician—not in an outpatient setting at least. If there is, they must be incredibly hard to find. (I would, of course, love for somebody to prove me wrong in the comments by letting me know where all the eating disorder doctors are hiding and how to find them!) It seems as though this kind of thing would only be available in HLOC (if even), making it completely inaccessible to anyone doing outpatient or DIY recovery. If I couldn’t find a doctor who was knowledgeable, then the best I could hope for was finding one who would listen.

“Levels of Care”

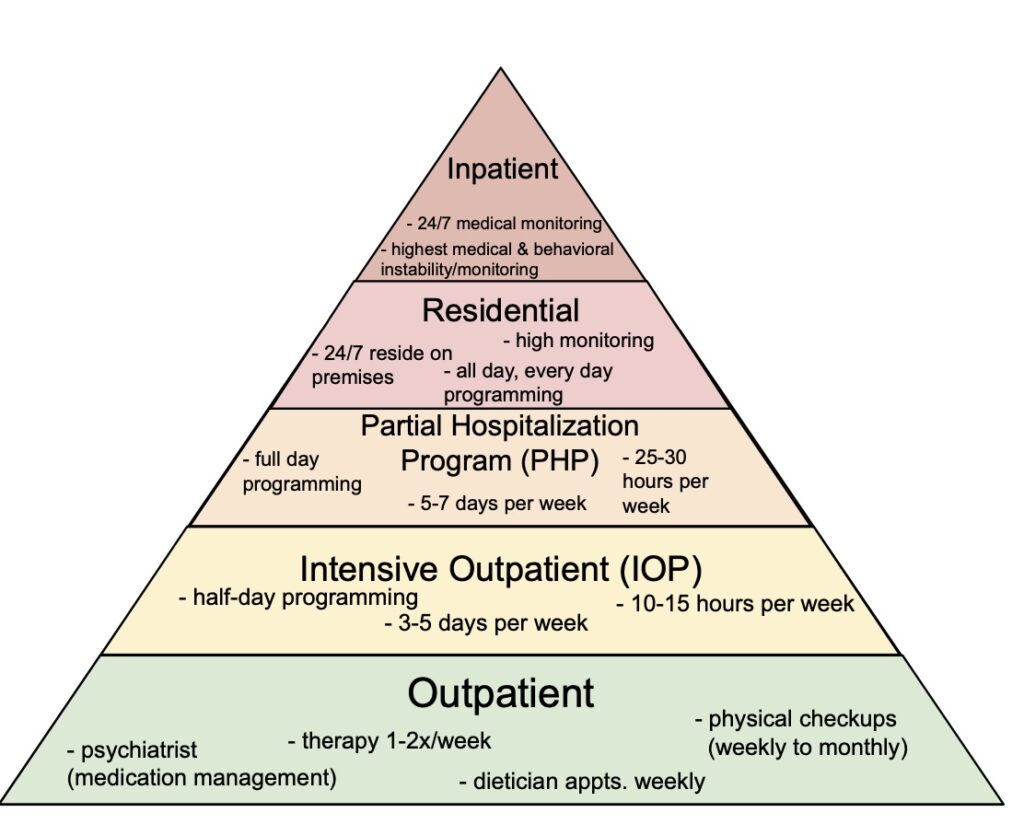

I think it’s essential that we talk about the inherent setup of eating disorder (ED) healthcare before getting any further. The several types of treatment offered exist on a hierarchy that presumably correspond to illness severity. These are called “levels of care,” and the more intense ones may be referred to as “higher levels of care” (HLOC).

Some of you may already be familiar with these terms, even if you do not have ED experience. This treatment model is not unique to ED treatment; however, it is especially prevalent in the field.

There are several problems with this setup. First of all, treatment tends to get more expensive the higher up you go, so treatment—of any kind, but especially HLOC—is not financially accessible to many people. Second, how does one determine the appropriate level of care for themselves? Well, they don’t; usually someone else does. Upon first glance, it appears that service users get a wide variety of tailored treatment options to choose from. However, often, this choice is not really up to the patient. It is up to some professional to (subjectively) evaluate how “severe” they think their illness is and assign them to a level accordingly.

One way this can play out: A patient seeks care at the outpatient level, attending therapy and nutrition sessions a couple times a week. However, after several weeks or months, they are not making much progress, so their “care team” decides—not only to simply recommend a higher level of care—but to coerce the patient into signing a treatment contract stating that they will be dropped as a patient and referred to a HLOC if they do not make a certain amount of progress by a certain date. The HLOC can, of course, then “reject” the patient if their case is deemed “not severe enough.” Consequently, the patient is left with no care options whatsoever. (This was basically exactly what happened to me.)

Third, this paradigm can cause patients to view symptom criteria as a sort of “checklist” that they must complete in order to access care. This can cause the “sick enough paradox” that I discussed in my previous essays (here and here). Patients are essentially trapped in a bind where they feel they must get worse (to access the care they need) in order to get better. In many cases, patients are led to believe that they are not unwell at all— that their behaviors are “healthy” even—leading to the notorious “denial of illness” so commonly associated with anorexia and other EDs.

Fourth, these “levels of care” are not only meant to correspond to supposed severity of illness and thus, frequency of medical monitoring, they also correspond with presumed “patient instability” and thus, intensity of behavioral surveillance. Meaning that patients may be admitted to higher levels of care on the basis of suicidality or self-harm—not just ED symptoms—and the higher the level of care, the less autonomy, agency, and rights the patient will be permitted, generally speaking. (I’ve heard of some residential treatment centers that don’t allow patients to shower or use the bathroom alone, despite the fact that ED patients are more likely to have trauma histories, including sexual abuse.)

But lastly—and this is the problem I’ve been running into—this treatment paradigm leaves little to no room for a self-determined recovery approach. (Perhaps this is by design.) Again, while there is overwhelming focus on the psychological side of ED healthcare— especially in outpatient settings—there is still an enormous gap in the physical side of it. For anyone who wants to manage the psychological/behavioral side on their own terms and doesn’t want or need therapy, psychiatric medications, or dietician-led “meal plans,” but still wants to know what is going on with their body and needs guidance on the physical/medical side as they recover from a “mental illness” with the second highest mortality rate of all psychiatric diagnoses, there are few to no options.

Under-researched and Undereducated

When finding ED-educated doctors to help me figure out my medical concerns turned out to be a fruitless endeavor, I eventually turned to self-education instead. I know how to read and interpret a research paper; I was a psychology major myself. So, I quickly got to work combing through the search results of Google Scholar. However, this approach quickly proved to have its downsides as well. What I found was that most studies are done on a small cohort of “clinically underweight,” white, cisgender, teenage girls with anorexia nervosa. Studies are typically short-term and done in hospital settings; long-term follow up is rare. Additionally, weight restoration is viewed as synonymous with recovery. (Spoiler: It’s not! More on that later.)

Although I do line up with some of those characteristics—I am white, cis, female, and in recovery from anorexia—I am certainly not represented by all of them. And most people with EDs are not. How are the results from these studies supposed to be generalizable to the majority of people with EDs? For that matter, how are the results from these studies supposed to be generalizable to adults? How can a 4-week or 6-week or even 12-week study tell me anything about what I’m going through now, almost 2 years into recovery, and still experiencing symptoms? How can it tell me anything about what to expect in the future?

I got to a certain point of desperation in my search that I almost decided to order a medical textbook (or several) on EDs. However, even just skimming through the table of contents in the previews of these books, I quickly discovered that they were rife with problems. As seems to be the trend here, around 80% of the chapters were dedicated to the psychological and behavioral profile of EDs, with only the remaining 20% focusing on the physical ramifications and how to medically test and/or care for them. Of that remaining 20%, judging by the titles alone, they didn’t look like they were going to cover anything I didn’t already know.

If what they are teaching in medical school about EDs—the tiny bit that they do teach—is based on studies and textbooks like these, then it’s no wonder why doctors remain so ignorant while certain stereotypes continue to dominate the narrative.

A Deeper Problem

The primary issue I’ve observed in healthcare—in regard to EDs, but also in general—is the inherent weight bias embedded in the field. Systemic fatphobia and medically embedded weight bias go hand-in-hand with poor eating disorder healthcare. While less than 6% of people with EDs are considered “clinically underweight,” and people in larger bodies are at the highest risk for developing EDs, medical providers and the general public alike continue to hold the stereotype that EDs only afflict those who look emaciated. When held in the minds of doctors, these stereotypes create a dangerous self-fulfilling prophecy: If doctors believe that only people who are extremely thin can have EDs, then they will continue to only diagnose and treat EDs in those who are extremely thin, thus confirming the stereotype that only the extremely thin have EDs. And fatphobia/weight bias—including stereotypes like these—affects more than just people in larger bodies: It harms thin people, too. Throughout my ED, I was thin, just not thin enough, according to some doctors at least. My weight—which fluctuated within a range from “normal-thin” to “underweight-thin”—did not necessarily correspond with how badly I was struggling, yet it did reliably correspond with how I was perceived and treated by others, both laypeople and medical professionals alike.

Furthermore, although scientific evidence has not demonstrated a causal relationship between weight and health outcomes, many doctors continue to recommend weight loss for heavier folks, and even praise weight loss in thinner folks as well. On the other hand, there is overwhelming evidence that over 95% of diets fail in the long-term, that weight cycling is a more reliable indicator of poor health outcomes than weight itself, and that weight stigma is more strongly linked than weight itself with many of the chronic diseases that are commonly associated with “obesity.” Meanwhile, what dieting and intentional weight loss efforts do reliably predict are an increased risk of developing an eating disorder. Though I could write an entire separate piece on this alone and how it parallels the issues we see in psychiatry—and I probably will at some point—for now, I will simply recommend the book Anti-Diet by Christy Harrison for anyone looking to dismantle their internalized fatphobia and abolish diet culture.

Another recurring theme I’ve encountered from healthcare providers when dealing with EDs is an attitude of ignorance coupled with arrogance. Ignorance with humility is more tolerable and less outright harmful, and can even lead to positive learning experiences, but ignorance plus arrogance can take on a malignant form. At my first appointment, my current GP validated my experiences by confessing that, yes, many doctors are notoriously arrogant, and yes, they are taught very little about EDs in medical school (any knowledge that is acquired is typically picked up on the job). For this reason alone, she is by far the best doctor I’ve found—not because she possesses any more expertise than previous doctors I’ve encountered, but simply because of her humble admission of unfamiliarity with EDs, and acknowledgement of the medical profession’s proclivity for self-aggrandizement.

Insurance Constructs, Profitability and Liability

There are many more problems in the realm of ED healthcare, and of course, my perceptions will be limited by my experiences. (I have never accessed care higher than the outpatient level.) However, a common problem I’ve encountered repeatedly—and heard from others as well—is that there is too much focus on weight in ED recovery at all levels of care. “But Jasmine,” you might be wondering, “I thought you wanted there to be more focus on the physical/medical side of things?” Yes, but weight does not equal health! Weight, when looked at in context (such as personal history), may simply be one data point in the constellation of health, but weight alone is not the whole picture. Additionally, such an over-fixation on weight in recovery can ironically mirror the illness itself. So why, then, is it used so frequently?

The answer to that question is the same reason why cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has gained so much traction in recent years: Because quantifiable results are preferred by insurance companies. Most of us probably know what a “social construct” is, right? Well, I would like to coin another, similar term: insurance company construct. Similar to a social construct, which is arbitrarily dictated by society, an insurance construct is arbitrarily dictated by insurance companies, without necessarily reflecting an objective reality. There is plenty of overlap, of course, between social constructs and insurance constructs: Psychiatric diagnoses are a perfect example. So is BMI (Body Mass Index). The idea of being “weight restored” is another. Like psychiatric diagnoses, this construct is not neutral; it can do great harm.

An over-focus on “weight restoration” in combination with recovery weights typically being set too low and forcing patients to reach these weights too quickly results in high relapse rates, chronicization of illness, and the notorious “revolving door phenomenon.” On far too many an ED recovery forum, I have witnessed others who have recovered from ED lamenting that they are still gaining weight or having symptoms or experiencing extreme hunger despite being “weight restored,” insisting that this means they should be “fully recovered” by now and therefore something must be “wrong” with their body. Under the right environmental pressures, this shame spiral can be the perfect catalyst for relapse. This is a tragedy. Instead of changing our bodies to fit the fantasy of a construct, we should change these constructs to fit the reality of our bodies.

However, unfortunately, I think this is by design, not by mistake. The revolving door phenomenon is remarkably profitable, as keeping patients sick ensures repeat customers. Under for-profit healthcare, there is very little incentive to actually help patients achieve a full recovery. Plus, there is a built-in shield from criticism. Instead of being seen as a failure of the system, it can be conveniently reframed as the nature of the illness itself being just oh-so-difficult to treat. Or better yet, victim-blaming patients as “non-compliant” or “not wanting recovery badly enough,” i.e. “maybe you’re just not trying hard enough!” Many patients, after several treatment attempts, are sold this idea that they have an incurable, lifelong disease that they will never fully recover from, resulting in hopelessness and shame.

In our liability-obsessed culture, it is no wonder why blame—and who gets it—is so important to the system and those who work in it. But acting out of this fear comes with a very real human cost. Much like “suicide prevention” interventions, forced treatment and involuntary hospitalizations can have worse long-term outcomes for eating disorder patients as well. Of course, getting someone physically stable is important in a life-or-death medical crisis, as can happen with EDs. However, often the way this is carried out ends up being traumatizing, degrading, and dehumanizing for the patient, leading to a high likelihood of future relapse.

But carceral practices don’t have to be as extreme as forced hospitalization in order to be harmful. As I mentioned earlier, treatment contracts, which are common at the outpatient level, can cause great harm as well. While being presented as a protective measure for the benefit of patients, in reality treatment contracts serve to protect providers from liability, even if that means betrayal of trust and emotional abandonment for their patients.

What I’ve Learned On My Own

Through my own DIY recovery, though I’ve stumbled upon many obstacles, I have still managed to glean a great deal of knowledge (and perhaps even more wisdom). I will list some of the things I’ve learned below, in case they would be of service to anyone else in similar shoes.

First, doctors are not omniscient or infallible. There are limits to their knowledge, especially when it comes to eating disorders, and trust should be earned, not given automatically. I am the foremost expert of my own body, and I can make my own informed choices instead of uncritically following everything they say. Furthermore, before any medical appointment, I like to come up with a list of specific questions and goals for the appointment. I can also set boundaries if needed, such as asking to be blind-weighed or declining to be weighed at all. If I am getting labs done, I like to remind myself that “good labs” do not always equal good health. The body has many methods of compensating for restriction that allow labs to still fall within “normal” ranges. It doesn’t mean I’m “not sick enough” or that I “should be” recovered by now.

Second, self-education is a powerful tool. Dismantling diet culture, unlearning my own internalized fatphobia, debunking the pseudoscience of BMI, and learning about science-backed anti-diet frameworks like Health At Every Size (HAES) and Intuitive Eating have helped me to tackle these issues at the systemic level rather than just focusing on my own individual “pathology.” (Again, I highly recommend Anti-Diet by Christy Harrison.) Additionally, learning from others’ lived experience with recovery can sometimes be even more helpful than academic reading. It has helped me feel less alone and realize that my experiences are normal, and has introduced me to concepts such as “extreme hunger,” “overshoot weight,” and “set point weight theory.” However, it can also be a double-edged sword, as I’ve learned to be wary of self-comparison; my recovery journey is my own and may not look the same as someone else’s.

Third, my body knows what it’s doing. My body will learn to trust me once I learn to trust it. I’ve shifted my goal from being “weight restored” to being “trust restored.” Overshoot weight—the phenomenon of bodies gaining back more weight than was lost after a period of starvation—is normal, healthy, and usually temporary. (This is part of why “weight restored” is a meaningless concept.) Having “excess” body fat is necessary for healing the damage done by restriction and reestablishing body trust. I must relinquish control over my body’s shape/size/appearance and trust my body’s innate wisdom and ability to self-regulate. It will eventually find its set point weight on its own timeline, without deliberate effort or intervention.

Similarly, when it comes to “extreme hunger,” the only way to “overcome” it is by giving in to it. I cannot control my body’s needs, and I cannot “outsmart” or “trick” my body into being satisfied by less than it needs. My nutritional needs may be different from what’s considered “normal” right now; I’m making up for a deficit. It won’t last forever. Same goes for all other residual symptoms I am still experiencing. There’s no telling how long it may take, but I trust that my body will figure things out in time.

And finally, last but not least: Although the state of ED healthcare is undeniably atrocious, and I am in no way excusing that or trying to find a silver lining, part of what recovery is all about is embracing uncertainty. With that comes giving up the ability to predict or control exactly how it will go. In order to regain trust in myself and my body, I must stop outsourcing my self-knowledge to “experts.” Of course, proper medical guidance would help things be a lot less scary, and a lot safer, too, but not because it would provide me with some perfect recovery “formula” or “roadmap” or “blueprint” or anything. The role of medical care would ideally be a collaborative one, not an authoritative one. Ultimately, recovery is a creative act; the kind of story where you make it up as you go. And I get to be the author.

“Most of us probably know what a “social construct” is, right?”

No.

“In order to regain trust in myself and my body, I must stop outsourcing my self-knowledge to “experts.””

Yes.

Report comment

This is a fine article but can we stop having “survivor stories” from psychology majors? I came here to get AWAY from the drowning voices of “””experts””” thank you very much.

It does not surprise me at all that there are no eating disorder doctors. It fits with how this culture treats weight as both a convenient and proportional summary of one’s physical health, and also one that’s entirely within one’s willpower to control. Like they completely forget we exist in symbiosis with our bodies, not as the master controller. Hunger exists so our bodies can control us, and it’s not impressive or a show of willpower to ignore it.

Report comment

My sibling has weakened under psychiatric care (nursing home). However, this is not healthy weight loss. He/She is losing weight without exercising. The factors causing his/her weight loss are psychiatric medications, irregular eating habits, and the gloomy environment of the nursing home. When we went there, he/she said that he/she could not eat. When we reported this to the psychiatrist and the nursing home… they said that nothing like that was happening and that his/her condition was good. But they were lying.

Yasmin, similar research like yours is important from this perspective. Psychiatrists and doctors do not want to take responsibility for such health issues. They place the blame on the patient. And usually, they do nothing in this health problem. The reason for this, we can say, is the widespread culture of cover-up between mainstream medicine, mainstream psychiatry, and pharmaceutical companies.

Thanks Yasmin. An excellent article on eating disorders….

Report comment