A group of researchers recently found serious bias in the reporting of harm due to adverse events in antidepressant medication clinical trials. They report that although dropout rates from studies for both drug and placebo groups were comparable and well reported, participants who were randomly assigned to receive the drug were 2.4 times more likely to leave the study due to adverse events.

More strikingly, serious adverse events were very poorly reported in journal articles. Even when they were reported, discrepancies were often found between data submitted to the FDA and those reported in the published literature, which is a form of “spinning data” or a way of using language to report results in a way that shows favorable outcomes for the drug while minimizing its negative effects.

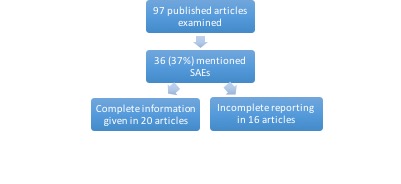

“In 79% of all journal articles, SAE data was incomplete or missing. Almost two- thirds failed to mention SAEs entirely, and an additional 16% of articles provided incomplete information regarding SAEs. For instance, some articles provided only the number of SAEs, without any description. Given the idiosyncratic nature of SAEs, such numbers have little meaning,” the researchers write.

In clinical trials, the FDA defines adverse events as any “untoward medical occurrence” that can be associated with the use of a drug, whether or not the investigator of a clinical trial thinks that the medical event is drug related. Some examples of adverse events include headaches, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Serious adverse events (SAEs) are those “that results in death, hospitalization, disability or permanent damage, a birth defect, or any other life-threatening situation.”

In clinical trials, the FDA defines adverse events as any “untoward medical occurrence” that can be associated with the use of a drug, whether or not the investigator of a clinical trial thinks that the medical event is drug related. Some examples of adverse events include headaches, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting. Serious adverse events (SAEs) are those “that results in death, hospitalization, disability or permanent damage, a birth defect, or any other life-threatening situation.”

All such events that occur during the period the drug is being actively taken or up to 30 days after it is stopped must be reported to the FDA. In order for patients and clinicians to make informed decisions about whether or not to take or prescribe a drug, the full picture of possible risks and benefits associated with the drug must be presented.

In this study, the researchers looked at all clinical trials for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as well as other antidepressants mirtazapine, bupropion, and nefazodone that were approved between 1987 and 2008.

“We included a total of 133 trials, consisting of data from 31,296 participants, of whom 18,904 were treated with antidepressants and 12,392 with placebo,” the researchers said.

They compared the reports for these studies published in the academic literature with corresponding reviews of the same studies submitted to the FDA and were interested in two things – the reporting of SAEs in general as well as discrepancies between these two data sources. With respect to reporting, information on SAEs was missing in 43% (57 of 133) trials. This was also reflected in the published articles:

In terms of discrepancies, only 21 of 36 published articles that mentioned SAEs (58%) could be directly compared because of “insufficient information in the FDA review.” Of those 21, only 6 articles had no discrepancies compared to the corresponding FDA review. In 7 of 21 articles, the discrepancies made it seem like the placebo group had more numerous or severe SAEs, thus wrongly indicating that the drug had more favorable outcomes.

In terms of discrepancies, only 21 of 36 published articles that mentioned SAEs (58%) could be directly compared because of “insufficient information in the FDA review.” Of those 21, only 6 articles had no discrepancies compared to the corresponding FDA review. In 7 of 21 articles, the discrepancies made it seem like the placebo group had more numerous or severe SAEs, thus wrongly indicating that the drug had more favorable outcomes.

The way this was done in published reports ranged from omitting or underreporting SAEs in the paper to not properly describing what the SAE was (e.g using the words “emotional lability” to mask a suicide attempt). One article even overreported the number of SAEs for the placebo group, in direct contrast to the number reported in the FDA review. These discrepancies are often explained as being due to judgments made about not including SAEs that site investigators judge as unrelated to medication – however, the basis of these judgments is highly subjective, leading to further bias in the reporting of SAEs.

The researchers rightly point out that this is an alarming trend given the association of antidepressant medication with suicidality, particularly in children and adolescents and violent crime. Moreover, these results do not even begin to address the long-term side effects of antidepressants, which are troubling given the trend that these drugs are increasingly being prescribed for long-term use.

A topic that this article did not address is the actual measuring of adverse events, and how this is done. For example, given that sexual dysfunction is often reported as a side effect of antidepressant medication, researchers have documented how trials rely on participants spontaneously reporting these effects instead of being intentional about the collection of such data. This leads to an inaccurate overestimation of drug safety.

The researchers mention the limitations of their analysis as having to work with incomplete FDA data and not examining common adverse events. They conclude, “We found that reporting of the actual discontinuation rates was unbiased, but many journal articles conclude, in their abstract, that the antidepressant was ‘safe,’ ‘well-tolerated,’ or both, even though antidepressant-treated participants were, on average, 2.4 times more likely to discontinue due to adverse events than placebo-treated patients.”

****

de Vries, Y. A., Roest, A. M., Beijers, L., Turner, E. H., & de Jonge, P. (2016). Bias in the reporting of harms in clinical trials of second-generation antidepressants for depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. European Neuropsychopharmacology, doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.09.370 (Full Text)

Wow, who would think they’d be so UNETHICAL! Shocking, just shocking…

Report comment

As someone who has been grievously harmed by an antidepressant, I find this article both disheartening and infuriating at the same time.

Plain and simple this is a COVERUP! Yes Steve, so shocking that the industry would put profits over safety. Grrrrrrrrrr

Report comment

As one of the millions of Americans, who had the SAE’s of an antidepressant misdiagnosed (according to the DSM-IV-TR) as “bipolar,” I’d like to point out this as a problem, “All such events that occur during the period the drug is being actively taken or up to 30 days after it is stopped must be reported to the FDA.” Because the antidepressant withdrawal SAE’s don’t stop at 30 days. These are the symptoms of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome:

“flu-like symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, sweating), sleep disturbances (insomnia, nightmares, constant sleepiness). Sensory and movement disturbances have also been reported, including imbalance, tremors, vertigo, dizziness, and electric-shock-like experiences in the brain, often described by sufferers as “brain zaps”. Mood disturbances such as dysphoria, anxiety, or agitation are also reported, as are cognitive disturbances such as confusion and hyperarousal.”

Since these antidepressant withdrawal effects are now commonly known, it is inappropriate for them to be called “idiosyncratic.” And in reviewing my own medical records, it becomes quite obvious, that I initially suffered from the “flu-like symptoms,” and these were misdiagnosed and mistreated. Then I started suffering from the “sleep disturbances.” And I did not start suffering from the more serious withdrawal effects, like the “brain zaps,” until about a year after I was abruptly taken off the antidepressant (“safe smoking cessation med”). And, of course, these were misdiagnosed as “bipolar.”

The SAE’s of antidepressant withdrawal last much, much longer than 30 days. I’ve had “brain zaps” for 16 years now. The “bipolar” drug cocktails do not cure the withdrawal symptoms of the antidepressants. And if you add an antipsychotic to an antidepressant, it can make a person “psychotic,” via anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

The DSM is a classification system of the iatrogenic illnesses created with the psychiatric drugs, not a classification system of genetic illnesses. And what’s really sad is it took me 12 years to find a doctor intelligent enough to comprehend this, and take the “bipolar” misdiagnosis off my medical records.

Report comment

The FDA never asks the participants. It relies solely on reporting.

What sense is there in having a researcher describe my experience to an examiner?

But then, the FDA is most likely not impartial.

Best thing is to get the word out to people. Educating them on the DSM, and on serotonin.

And how real studies, which are called experimentations, only happen after a drug is pushed, and

that each consumer continues to be a study and that the SAE’s will be denied by the prescriber.

They do not exist past the FDA allowing the drug.

Law suits should extend to the FDA.

We are prescribing suicide drugs to suicidal people. It sounds to crazy to the general public, so I must be delusional

Report comment

It makes sense why my adult son is so full of rage and in so much pain. He grew up with a psych drugged single mother in a highly dysfunctional family system. I was constantly being admonished to “get help!”. The help was psych drugs, always. When those didn’t work, more psych drugs. Leading to the crescendo of ECT, borderline dx, addition of anti-psychotics…I finally became officially “permanently disabled”. He was a teenager. The timing couldn’t have been worse. After being denied help multiple times as a suicidal teen (“she’s just looking for attention. It’s a cry for help. Ignore her “) I became a mother and by the time he was a toddler, Prozac was introduced as a “miracle drug”. How many who could have led normal lives got caught in the trap of the onset of the chemical imbalance theory — no one questioned it for at least 20 years. No black box warnings, no Surviving Antidepressants, no MIA. There was no counternarrative. I couldn’t extricate myself. I kept getting in deeper and deeper. My son grew up in hell.

Would I have done better as a single mother had I not been incapacitated by psych polypharmacy? I don’t think I could have done worse.

Report comment