Increasing the minimum wage reduces instances of child abuse in the home, finds new research from the Children and Youth Services Review. By examining how increases in minimum wage decrease rates of child maltreatment, researchers and policy makers alike can work together to enhance family and child welfare.

“Our results suggest that policies that increase incomes of the working poor can improve children’s welfare, especially in younger children, quite substantially,” the researchers write.

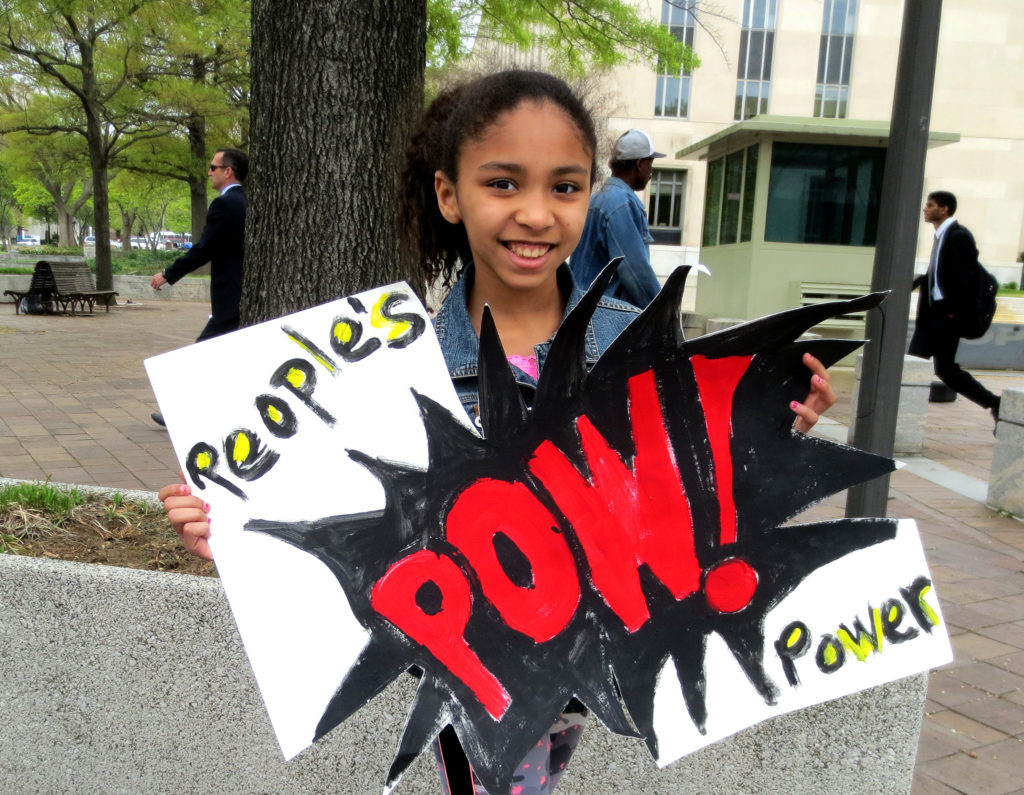

Photographer: Kara Smith.

Children living in households at the poverty line are “five times more likely to experience maltreatment than children in higher socioeconomic status families,” and constitute the highest involvement with child protective services. This correlation can, in part, be explained by the inability of a low-income earner to provide basic needs in the household such as food, shelter, clothing, medical care, appropriate home environment.

The low income earner often serves as the caretaker and breadwinner, balancing running the household and paying the bills, leaving limited time for play, let alone self-care. Therefore, child neglect is the form of abuse most positively responsive to an increase in minimum wage, giving the caretaker more time and less worry about providing basic needs.

Women would be key beneficiaries of increased minimum wage, as they represent the typical minimum wage earner. This is particularly pertinent as it is commensurate with prior research indicating that 68% of maltreated children are harmed by a female caregiver. Though low-income women are at risk for harming their children, it should be recognized that most of these women do not. Rather, understanding the typical minimum wage earner’s profile and their rates of child maltreatment illuminates another correlation between income and child welfare.

An abundance of research has shown that child maltreatment is linked with economic hardship. Researchers Raissian and Bullinger took this research a step further to examine if increasing the minimum wage reduces child maltreatment by reviewing child maltreatment reports from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System between the years 2004-2013 in nearly all states.

“The literature has shown a link between even modest increases in income and a decrease in child maltreatment,” they write. “Therefore, we expect to observe a decrease in child maltreatment following an increase in a state’s minimum wage.”

The researchers analyzed child abuse data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS), consisting of reports detailing the type of abuse and if it was corroborated. Data regarding state and federal minimum wage was extracted from the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) and the University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research. The results revealed that a $1 increase in minimum wage led to statistically significant declines in neglect reports, specifically 10.8% decline in reports for young children (ages 0-5) and 9.2% decline in reports for school-aged children (ages 6-12).

It should be noted that most cases of child maltreatment go unreported and this analysis utilizes those reported to child protective services. Additionally, more research is warranted in order to understand how the increase in minimum wage operates to decrease child maltreatment.

The researchers point out that debates surrounding minimum wage are usually divisive and politically charged. This finding shifts that rhetoric towards the unattended effects of raising the minimum wage which saves child welfare costs and provides “unquantifiable benefits of keeping a child from experiencing maltreatment.”

“Immediate access to increases in disposable income may affect family and child well-being by directly affecting a caregiver’s ability to provide a child with basic needs such as being able to afford appropriate clothing, more food and nutrients, taking the child to a physician for medical care, or better home conditions.”

****

Raissian, Kerri & Bullinger, Lindsey. (2016). Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 60-70. doi:1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.033. (Link)