Updates to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth revision (ICD-10) are currently underway in preparation for the 2022 release of the ICD-11. To inform the forthcoming change, an international team of researchers led by Corinna Hackmann gathered input from those most directly impacted by the disease categories and their criteria: people with lived experience. In their article published in The Lancet Psychiatry, Hackmann and colleagues emphasize that service users experiences of diagnoses are critical to the construction of meaningful revisions by WHO.

Participants with at least one of the five diagnoses included in the investigation (i.e., depressive episode, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar type 1 disorder, and personality disorder) were exposed to both clinical and layperson draft guidelines. Focus groups were conducted to elicit feedback, which authors then analyzed for themes and compiled in a summary report to WHO. Although the first edition of the ICD was published in 1893, the eleventh edition will be the first to integrate service user perspectives formally.

“The value of expertise by experience in innovation, service provision, and research is increasingly recognized by policy makers, service providers, and researchers.”

The ICD-10 comprises a comprehensive inventory of human diseases and disorders, guiding practice in 194 member states to date. Its single chapter outlining behavioral and psychological disorders represents the foremost resource applied in the classification of mental disorder internationally. Similar in many ways to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the ICD-10 is not without its flaws.

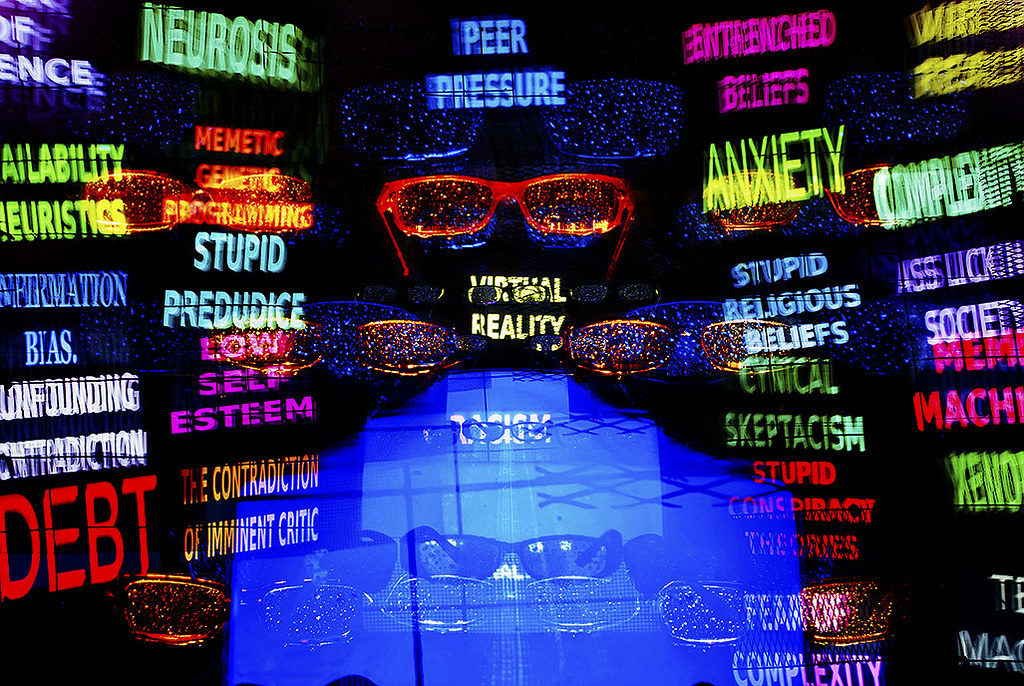

Authors note that diagnostic criteria for psychological disorders profiled in the ICD-10 are simultaneously technically dense and accessible for service users to find. Many service users have expressed that ICD-10 language does not resonate and can be stigmatizing.

To address the critique that conceptualizations of disorder and language used in the ICD-10 may be discrepant with service users’ experiences of their identities, and acknowledging the social and emotional contextual implications of psychiatric diagnoses, researchers aimed to “-gain an understanding of the way that service users respond to the content of the major diagnostic systems.”

Behavior and subjective experiences deemed disordered, disruptive, deviant, destructive, etc. depend heavily on contextual circumstances and climate. Service user voices are therefore paramount to quality change guided by experiences in homes, schools, communities, etc. outside of research and clinical environments alone. Research conducted by Hackmann and team, while a small chip off an enormous iceberg, reflects a response to calls for a philosophical reconceptualization of the mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental portion of the next generation ICD.

Focus groups, featuring a total of 634 participants (two to 10 per group) were conducted in India, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Participants were required to have been diagnosed with one of the five aforementioned disorder classifications (comorbidity was considered acceptable), to have received related services within the past five years, and to speak English (or Hindi if in India). All focus group participants received the same materials and participated in a semi-structured conversation with set discussion points related to language and broader characteristics of new guideline drafts.

Results, summarized in an additional report for reference by WHO, indicated that:

“Participants identified additional features for all diagnoses. These additional features mainly reflected internal experience (e.g., pain or distress). […] Participants identified instances when features did not resonate with lived experience. […] Participants also identified that features tended to reflect the external perspective of non-service users. Classification systems operationalize features and priorities what can be described from an external perspective to enhance reliability and support clinical use. Our data suggest that this operationalization might have the unintended consequences for service users of feeling alienated, misunderstood, or invalidated.”

Researchers stressed commitment to international service user representation and adequate representation in diverse service user profiles (e.g., age, gender, etc.) when sampling; and quality in coverage of prevalent diagnostic categories. However, scope remains a limitation given the global ground the ICD-11 is projected to cover. Nonetheless, Hackmann and team’s efforts, and WHO backing, represent momentum behind what many hope will be more than a nod to the aphorism “nothing about us without us.”

“Our study represents an overdue milestone and a watershed moment in mental health research. It is the first time that service users have participated in systematic research to provide review and recommendations on proposed diagnostic guidelines for a major system. Given this novelty, it is worth remarking that the proposed guidelines were in many cases perceived as useful and relevant to lived experience. […] Crucially, our study validates the essential engagement of service users and the essential role of co-production.”

****

Hackmann, C., Balhara, Y. P., Clayman, K., Nemec, P. B., Notley, C., Pike, K., . . . Shakespeare, T. (2019). Perspectives on ICD-11 to understand and improve mental health diagnosis using expertise by experience (INCLUDE Study): An international qualitative study. The Lancet Psychiatry. (Link)

Let’s take into account the voice not of all at once, but of one specifically taken person. James Eagan Holmes. According to his mother, he had a psychosis (acute psychosis I guess). It can be assumed that psychosis was caused by use of vaporizer plus strong marijuana variety with a THC content of about 20%. This can be assumed since all his actions, including the most insignificant, exactly repeat the picture of cannabis induced psychosis (in chronological order). In other words, for people who have experienced such a psychosis, this is not a secret. Equally obvious is the fact that psychiatry must protect society from such people (since historically, it’s not the task of the church?!). But how to find out that someone in the future will decide to smoke a lot of marijuana with vaporizer (obviously because works out?) According to available information, there are early signs. For example, if a child is well developed physically or smart enough to go to graduate school – psychiatry should register such people and nurses should regularly come to their home. If it turns out that person has not been taking a bath for a long time, likes to be at home, rude to a nurse, does not open the door, or started smoking cigarettes – then these are already psychotic symptoms. And such a person can be given the appropriate diagnosis.

Report comment