Greg Hitchcock is standing and schmoozing with a cluster of people in the soaring, glass-domed rotunda of what once was a grand old bank — now a chamber-of-commerce gallery space — on a corner of downtown Gloversville, New York.

In just a few minutes, he’ll be screening a rough cut of his newest film: Pioneer Days: Fire in the Valley, a documentary short examining the centuries-long violence and discrimination endured by the Haudenosaunee, the alliance of Native American nations also known by their French-coined name, the Iroquois.

It’s a big night for him as a filmmaker. A big night for him, as well, as a writer and journalist determined to highlight the experiences of people struggling to be heard. And as a human being diagnosed with schizophrenia, it’s huge — yet more affirmation, yet more proof, that the voices he hears have never stifled his own. They only moved his life onto a different path.

“I had to go into a completely new direction,” he says of the sudden turn first thrust upon him nearly 35 years ago. It’s been a long road, and a bending one.

But here he is, in early May, prepping to unspool his most recent documentary at a public event. Certain COVID protocols are still in place, and attendees are wearing masks when they aren’t noshing on appetizers. Hitchcock is wearing one, too, his eyes wedged between stretchy orange fabric and a snappy black fedora.

On the walls around him hang some of his comics and other drawings, expressions of a creative urge that has kept him going since childhood. He always had a knack for it — for drawing, for writing, for storytelling. As a kid growing up in the Albany area’s suburbs, it helped him relieve tension and anxiety. As an adult, it’s helped him weave through the world with meaning. And in a way, he says, his lived experience itself informed his art.

“I think that a lot of people with, maybe, mental disorders are more creative that way, because they can think outside the box. . . . I mean, especially with schizophrenia. The thoughts come to you, and you just say, ‘Wow. I can do this. This is happening.’ And I react to it. And I think the voices might be an impetus to trying to find my way.”

“There was hope for me”

The first time he heard them, he was in the Army.

It was 1986. He was not quite 20. Six years earlier, his parents had split, and he’d moved out with his mother to a new town, a new school. It rattled him a bit. He had a hard time adjusting, and he turned inward. When he graduated high school in 1985, he wasn’t sure what to do — college? A job? He didn’t know. “So I decided to go into the military.”

After basic training, he was tapped for an electronics repairman job and sent off to fix TVs and radios at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. The drudgery of the work, the constant exposure to sick and dying people, the roughness of the neighborhood he lived in — all of that affected him. “I got a little paranoid,” he says. He started to worry that people were following him.

In his off hours, he would ride his bike to a video store in Silver Spring, Maryland, renting grisly World War II documentaries and morbid horror flicks — including Faces of Death, a 1978 feature packed with all sorts of ghoulish scenarios. Say, a skydiver whose parachute won’t open. Or sharks eating humans. Or humans eating monkey brains. “It was all this weird stuff I was going through,” Hitchcock recalls.

Then, one day, he heard a whisper. He describes the moment in his short, vivid 2012 book, Schizophrenia in the Army, which details both the onset of his condition and his ongoing recovery:

“Greg,” it said at the post commissary.

“Greg,” it said when I walked into the mess hall.

“Greg. Greg. Greg.”

Every time I heard my name called, it was always from the back of the room, as if someone was trying to sneak up on me. But, every time I turned around, no one was there.

That’s all the voices ever said: his name. But they got louder and louder, he says. At night he would head out to bars and try to drink them away. It never worked. Things only got worse.

Then, one day, his commanding officer stopped by his room for a routine inspection. “The room was disheveled,” Hitchcock says. “And I had smeared some of my feces on the wall.”

The CO, believing he’d had “some sort of psychiatric breakdown,” sent him off to Walter Reed for an evaluation. There he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, receiving various forms of therapy — art therapy, cooking and baking, a recreation program — in addition to meds. Doctors put him on 100 mg of Mellaril daily; as a result, he wryly observes in his memoir, “sleeping was not much of a problem.”

He was admitted on December 11, 1986, four days after his 20th birthday. He was discharged the following April.

Reflecting on those days, Hitchcock calls his diagnosis and initial hospitalization “my darkest period in life.” Being diagnosed with schizophrenia, and being told it was a permanent condition — “That’s one of the things I was upset about. . . They said there was no chance of going back in the Army,” he says, “because it was lifelong.”

At first, “I did have suicidal ideation, suicidal ideas. Because I thought that was the end of the road for me.”

At one point, a woman on the ward made a suicide attempt. It was around Christmas time, he says. He remembers hearing a shriek, then a rush of people bolting into her room. When Hitchcock asked an orderly what happened, “He said, ‘Well, somebody tried to take their own life.’ And I said, ‘wow.’ . . . . That woke me up, saying, ‘Life is not cheap,’ you know? It’s not cheap. It’s valuable.”

The power and joy of telling stories

This epiphany — the conviction that he should hold on, no matter what his struggles — began to inch him forward. He started to help other people. After securing day privileges, he started making bike runs to the video store for his fellow patients, renting not twisted horror films but light-hearted comedies, mostly. Plus One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which made everyone laugh.

“That gave me a sense of mission and accomplishment,” he says. He didn’t have that in the beginning, “and it made me feel validated. . . . It made me feel validated, it made me feel there was hope beyond the hospital ward, the hospital walls. That there was hope for me.”

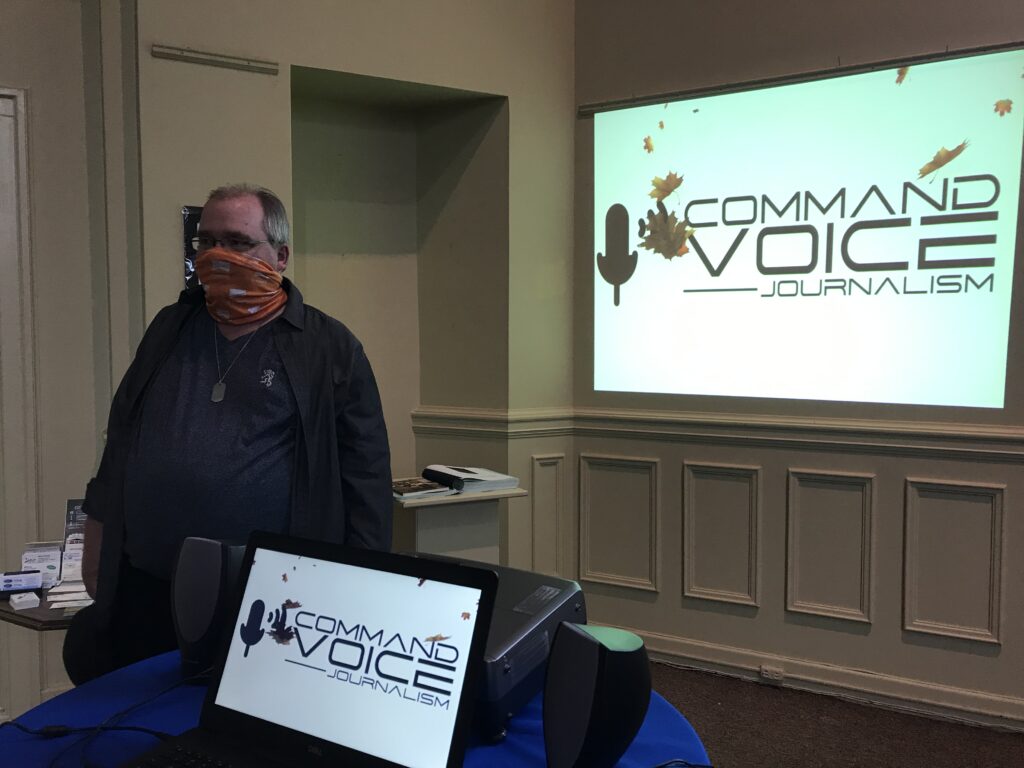

That sense of hope quietly shaped the decades that followed, helping him navigate all the many chapters and challenges in his life: his honorable discharge from the Army and placement on permanent disability; his time in college, ultimately graduating with a bachelor’s degree in English from SUNY Albany in 1992; his continued treatment, both inpatient and outpatient, at a nearby VA hospital; his halfway house experiences; his venture into journalism; his work as a staff reporter for the Leader-Herald in Gloversville; his creation of his own website, Command Voice Journalism; his freelance work for other publications; his dive into filmmaking.

Somewhere in the middle of all this, another epiphany hit him: “That I loved to tell stories. I loved to hear people’s stories through interviews, and that got me stronger.”

The foray into filmmaking — “that was just a leap of faith,” he says. His first ever was a 2011 documentary on St. Mary’s, an historic Catholic church in Albany; his first to get some notice was Climate Change: The Adirondacks, a five-minute documentary produced for a United Nations project.

“I felt myself saying, ‘Wow, I can do documentaries, too.’ And I loved it. I loved going around, talking to people. . . . I enjoyed it so much that I decided to pursue it as a second stream of income for me.”

Since then, he’s done an assortment of films on an array of topics — on heroin addiction in nearby Amsterdam, on the Rice Homestead historic site in Mayfield, and on the 50th anniversary of the Woodstock music festival.

His film on the Haudenosaunee, meanwhile, had a rapid-fire turnaround. In February, Hitchcock received $1,000 from a locally administered program awarding microgrants for explorations of systemic racism around the region. In March, he started shooting at varied locations, including the Akwesasne Mohawk Reservation in New York’s North Country. Two months later, his rough-cut screening in Gloversville. The finished work is now viewable on his YouTube channel.

Eventually, Hitchcock hopes to sell the rights to a distributor specializing in high schools and colleges. Most of his films have an educational thrust, he says, emphasizing both problems and solutions. “I want people to know that there’s always a different side to everything . . . And I like to be part of that. I like to play my small part in educating the public that there’s a better way out there.”

You gotta have connections

After chatting with a few more folks in that soaring former bank lobby, Hitchcock then eases over to a laptop and screen set up the side.

The documentary is not quite finished, he explains. He still needs to shoot a few more sequences. But as he introduces it, the spark of accomplishment in his gaze — still wedged, for now, between hat and mask — is palpable.

“I want to show you this,” he announces. And then hits play.

Pioneer Days opens with the Haudenosaunee creation story: the twins born on the back of a turtle island, the balance of Mother Earth, and the divisiveness of humans. From there, mining interviews with historians, the documentary delves into the Colonial era: the arrival of Europeans, the development of the fur trade, the competition that ensued, the strife that erupted, the onset and aftermath of the Revolutionary War.

The film considers all the outrages and their impact on the Six Nations, their territory destroyed and their communities upended. But in the final section, flecked with hope, it turns to the voices of the Haudenosaunee today as they reflect on lingering prejudice and their efforts to keep their traditions and language alive.

One woman, sitting in front of the Akwesasne Freedom School, recalls the children once punished for speaking their Native tongues and ponders a future without racism. “I don’t know,” she says. “Is that possible?”

Another woman, an Onondagan, mulls diversity and division with the same air of longing.

“It’s respect for a person’s being, their essence, their spirit, you know. You don’t look at them differently because they’re different. . . It’s all one and the same,” she says, as piano music swells. “We’re here for the purpose of learning, living life, and sharing.”

The film then wraps with narration, citing the activism and achievements of Indigenous peoples. Violins join the piano for an upbeat close.

“That was it!” Hitchcock says to applause. A viewer shouts out: “Good job, Greg!”

Afterward, he works the room. Milling about are relatives, friends, and his fiancée, Luanne Williams. Also present are friends from his church, Mayfield Central Presbyterian, where he sings in the choir — he’s a tenor — and helps with the website. He’s produced a few films for them, as well.

“Hi, Bonnie!” he says, greeting his pastor, the Rev. Bonnie Orth.

“Hi, Greg!” she replies, grinning.

Her take on the film? “Great. Fabulous. Really good job.” Her take on the filmmaker? “He’s a multitalented gentleman.”

They go way back, Hitchcock says. At least 15 years. So many of the people in attendance he’s known for just as long, some even longer. He’s lived in Gloversville for six years now, in the wider region pretty much forever.

“You gotta have connections,” he says.

It doesn’t always have to be scary

His sister, standing nearby, is proud. Susan Danna is happy for her brother. But she’s also far from surprised.

This is what he does, she says. He creates. The films are a newer development, but in a way, they merge all of his gifts and interests — his artistic spirit, his passion for history, his love of interviewing, his knack for storytelling, even those comics he drew as a kid.

“He’s a very good communicator. He just knows how to talk to people. . . . He’s very talented at — what do I want to say? — at empathizing with people. And I think that’s why he enjoys it so much.” His lived experience plays a part, too. “Everything comes out in his art. I think his talent is created from the visions that he has in his mind that other people don’t. So I think that’s how he expresses himself.”

And another thing. “He’s just a very sweet person.”

In ages past, those with voices and visions were seen as touched by the divine. In modern times, no longer. “Yes,” his sister says, “because you think it’s negative. You think it’s scary. And it doesn’t always have to be scary.”

His initial diagnosis, and being told it was lifelong — that was hard to accept, Hitchcock says. It wrecked all of his plans. He left the Army; he went on disability; and he started looking for some new way, some new reason, to move forward.

“I finally found it,” Hitchcock says, “and life’s been good since then. Yeah. I found a mission, a sense of purpose.”

What’s clear, from his words and his manner as he moves his way around the crowd, is that he’s whole. His life is full. His connections are many. He has a career, loved ones, a sense of purpose, and a sense of compassion that binds him with others in distress. His diagnosis hasn’t stopped him from writing, or making friends, or making films. It hasn’t stopped him from creating, or achieving, or giving.

“You just don’t come out and say, ‘I’m disabled,’ because if you say you’re disabled, there’s a brick wall in front of you right there. But if you say, ‘Yeah, I’m abled, and I have an ability,’ then that brick wall disappears. You’re able to do things.” Look at all the folks with physical limitations climbing mountains, running marathons, competing in Paralympics.

“You have an ability, even though you might have obstacles in your path. Anybody has abilities. And I think we’re placed on this earth,” he says, “to give people a sense of what you’re capable of doing. And that’s what got me through my recovery, because when I was thinking about myself — when I was thinking about myself in the beginning — I was selfish. I just thought about myself. And that’s not a path to recovery. A path to recovery is going outside of yourself.”

Aside from his work for the church, he helps out in the community — among other things, doing peer-to-peer work with NAMI New York State. He also sits on the board of directors for the Mental Health Association in Fulton and Montgomery Counties.

Giving is a key piece of his life — “because that’s what got me out of my shell.” But not just for him. For anybody. “It actually connects you with other people,” he says, “and makes you feel positive about yourself by doing things for other people.”

“Keep on punching until you punch a winner”

These days, Hitchcock takes a small dosage of Abilify — 5 mg — and goes to therapy. Those are two pillars of his approach to wellness, he says. Another pillar is community and the balance of work and social life.

“My voices are still there,” he says. “They might have been muffled, they might have been silenced, but they’re still in the background. I don’t hear them as much, as vividly, as I used to, but I can still feel their presence. That’s why I do all I can to connect with other people — so they won’t be present.”

He regards his diagnosis with the same measured acceptance: “Even with medications and counseling, and how you live your life — if you live with schizophrenia, it’ll always be there. It’ll always be there in the background.”

Asked whether his experience has made him a better listener, Hitchcock replies: “Yeah. Yeah. It has.”

Asked how so, he replies: “In so many ways.” Then he takes a long pause, weighing his answer for six or seven seconds before he speaks again.

“If it wasn’t for my getting schizophrenia in the Army,” he finally says, “I probably would not have followed this path. I probably would still have been in the Army, with TVs and radios. I probably would still be doing something like that outside the Army. And I wouldn’t have the strength, or the know-how, to do all of this storytelling — if it wasn’t for the singular fact that I had to change my whole life around it, because I was released from military duty.”

That, once again, was the impetus. “I can say that. I can say that. If it wasn’t for my disability, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now. Because life turns on a dime.”

People with diagnoses like schizophrenia or anxiety — “it’s just like a phobia. You have to confront it and try to cope with it the best you can. And there’s a path to another life — if you just follow that path. . . . I am not trying to toot my own horn,” he adds. “I am not trying to become bigger than I am. I just want people to know that if you have a skill and an ability, you’re supposed to use it.”

So he does his best to mentor others, knowing how important his own mentors have been to him — telling him not to give up, showing him how to move forward. The late John Knopp, an old friend he knew from his days in a halfway house, was one such mentor; Hitchcock dedicated Schizophrenia in the Army to his memory.

His friend’s dad was a boxer, the filmmaker says. Knopp “always kept telling me to ‘keep on punching until you punch a winner’” — and the slogan has echoed in his mind and his life choices all the years since.

Does Hitchcock punch harder now for all he’s been through? Has it made him a more creative person, a better filmmaker?

“I don’t know,” he says. “I can’t tell you. But I just want to tell you that there’s strength inside people. It may seem bleak at times, but there’s strength inside people — and there’s a faith that you should get out of that funk, and get your strength, and move forward.”

Could you please elaborate more on the concept of disabililty? For committing to the advocate across the categories of race, sex, creed, gender and disability, the last concept seems to be hitting the brick walls for lack of informed physical and programmatical design. In Louisville, with the arrival of the ADA’s creation, the Metro dis-Abilties Coalition would be created. Even the head of the Presybtery USA would help with creating the founding By-laws. A great deal of discussion would be around the creation of the name, which to advocate becomes the challenge to embrace the whole of the existence. At times, people can be made to feel ashamed of the civil categories by which our governance is tasked to embrace and affirm in our Democracy. So, even though in listening to the architect of the 9/11 project come in and speak about the new building, when approached after his speech I would ask, about his thoughts about universal and green design. His response was “It’s all B.S.” So, if film can be shown or made of what a vision is seeing, then how does one create and advance that which is not understood now, though in the nature of our Constitution, there seems to be some words that affirm eualities of acess to the pursuit of happiness, even beyond the prevailing practice of mental health care and treatment.

Report comment

“In ages past, those with voices and visions were seen as touched by the divine. In modern times, no longer. ‘Yes,’ his sister says, ‘because you think it’s negative. You think it’s scary. And it doesn’t always have to be scary.'”

It is psychiatry, psychology, and big Pharma who have brainwashed the public into believing having “voices” and “visions” is “negative.” But I agree, it’s not always “negative” or “scary.”

As one who had a dream about being ‘moved by the Holy Spirit,’ mislabeled as a ‘Holy Spirit voice,’ which was supposedly proof of ‘psychosis.’ Resulting in a whole bunch of anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings. I will say anticholinergic toxidrome induced ‘voices’ are horrendous.

However, I was weaned off the drugs, by a psychiatrist, who eventually concluded that my psychologist had misdiagnosed me. Which was true. I had been misdiagnosed, even according to the DSM-IV-TR. I had had the common symptoms of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome misdiagnosed as ‘bipolar.’

But being weaned from the drugs resulted in a drug withdrawal induced ‘super sensitivity manic psychosis,’ or what I would describe as an awakening to my dreams, and an equating of my subconscious and conscious selves. The awakening was a staggeringly serendipitous experience, quite amazing really, it was as if I had perfect timing with almost all others on the planet.

Eventually I awoke to the concept that we are ‘one in the Spirit, one in the Lord,’ and I was supposedly judged by God to be ‘of the bride.’ I did have some ‘voices’ during this experience, but the majority were benevolent, not malevolent. They wanted to help me heal.

And basically all I needed to do to control those ‘voices’ was to politely explain to them that I couldn’t function with lots of ‘voices’ in my waking hours. They understood this. But I said, if all who are ‘one in the Spirit’ agreed that I needed to be forewarned of something, they could collectively speak to me. However, if all could not agree, I needed peace of mind in my waking hours. This worked.

None of this was ‘scary’ for me. And in as much as I may now actually have an occasional ‘Holy Spirit voice.’ It is a benevolent ‘voice.’ It is one that ‘moved me’ and assisted me in finding the medical proof that the antipsychotics can create ‘psychosis,’ via anticholinergic toxidrome. One that also awoke me in the middle of the night, and directed me to research into what ‘schizophrenia’ was. And also find the medical evidence that the neuroleptics could also create the negative symptoms of ‘schizophrenia,’ via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome.

This is information that should be considered very relevant to the psychiatric field. Although it is truthful information, to which the psychiatric industry does not want to admit.

During this entire experience, since anticholinergic toxidrome makes one ‘hyperactive’ not ‘inactive.’ I functioned as one of the ‘super mom’ volunteers in my neighborhood, and painted my experience of psychiatry’s iatrogenic ‘bipolar epidemic.’

My work has been called ‘insightful,’ ‘work of smart woman,’ and ‘prophetic.’ I’ve been called a ‘Chicago Chagall.’ But my work – both my art work and medical research – is ‘too truthful’ for the psychologists of my childhood religion, who want to ‘maintain the status quo.’ I had one psychologist, who blasphemed the Holy Spirit, misdiagnosed me, and had me poisoned. And another psychologist who attempted to steal all my money, work, and he wanted to rewrite my story. I said no to him, too many times to count.

I’m not certain when or why the psychologists of my childhood religion stopped believing in the Holy Spirit. But truly I believe that as a society, we should return to an understanding that some people with “voices and visions” are actually “touched by the divine.” And us Holy Spirit moved people are deserving of a lot more respect – than defamation with “invalid” disorders, and repeated attempts to kill and/or steal from us – because we believe in the Triune God.

I agree, “You gotta have connections,” and it was my friends – not “mental health professionals” – who helped me survive. But I was forced to move out of the state in which many of my friends live. Due to a criminal psychiatrist who, for years, illegally listed me as her “out patient” with insurance companies, when I was NOT.

And I had to leave my childhood religion, because the pastors, who claim to believe in the Triune God, but actually trust in psychologists, instead of God. Perhaps since they don’t have funding to support their local visual artists, so they think they should have the psychologists attempt to steal from us, instead of working to get funding for the visual arts? While they hypocritically claim to support the “arts,” but their church walls are bare. Nonetheless, the crimes of the pastors, psychologists and psychiatrists – who I’ve had the misfortune of dealing – make maintaining connections difficult.

Thank you for sharing Greg’s story, Amy. Thank you, Greg, for allowing your success story to be told. I believe dispelling the psychologic and psychiatric industries’ lie – that all who have “voices and visions” are “scary” and “dangerous” people – will go a lot further in “de-stigmatizing” unusual human experiences, than any of today’s “mental health” industries’ de-stigmatization campaigns.

Not all “voices and visions” are bad. Being ‘moved by the Holy Spirit,’ and even having an occasional ‘Holy Spirit moved’ “voice” – but usually it takes the form of a nod of my head yes or no, after a prayer – is good. And “visions,” even if such seems bizarre initially, can sometimes turn into really cool paintings. “What’s wrong with that, I need to know, ‘cuz here we go again….”

Enough, psychologists! My story is supposed to be a lyrical libretto love story, and a “hero’s journey” story, about how I found medical proof of the iatrogenic etiology of the “sacred symbol of psychiatry.” Not that the antipsychotics are the etiology of everyone’s “voices.” Since lots of non-genetic issues – like sleep deprivation, likely trauma, stress, street drugs, other psych drugs, etc. – can also cause “voices.”

Report comment

Thank you for this story. Greg has overcome so much and is inspiring. Well written.

Report comment