Birgit Valla, the editor-in-chief and initiator behind Mad in Norway, knows that when it comes to mental health, her country has one of the most admired systems anywhere.

It has comprehensive national health coverage. It has a Ministry of Health directive requiring each of the country’s four regional authorities to offer at least one small unit of non-medicated treatment in a public hospital. It has a full private hospital devoted to same. It has other public programs, in place in many of the country’s 428 municipalities, offering humanistic, community-based care. And it has a tradition of listening and inclusion across all social strata and demographic groups.

People from around the world look to Norway, she realizes. They want to emulate it. But still, she said, it has continuing problems with forced treatment and human rights violations. And those non-medicated units—those places of refuge where people can either stay off or taper off psychiatric drugs—are “a tiny part of the whole system. And the rest of the system is very heavily based on the medical model.” Those very units offer “sort of an oasis from the rest of the system,” she said. “So it’s not all rosy.”

A clinical psychologist and author of Beyond Best Practice: How Mental Health Services Can Be Better, Valla brought together the group of activists and professionals who created Mad in Norway a little over two years ago. Valla did so after originating, and leading, a non-diagnostic, community-based mental health service in the Stange municipality.

From the start of her career in psychology, “It very early became clear that there was something wrong with the way mental health, the way the system, was set up—and how we were thinking with the diagnoses.” But saying so was out of the question. “You weren’t taken seriously. You were a charlatan, or something.”

When Valla first read Robert Whitaker’s Anatomy of An Epidemic, she thought: “Finally, my thoughts are being validated.” But Norway’s mental-health establishment is conservative, she said; practitioners within the system are hesitant to criticize it or refute the official guidelines, which legally require them to diagnose. So she was reluctant to speak out until she read two more books, both by UK authors: Cracked by James Davies and Prescription for Psychiatry by Peter Kinderman.

“It was after that that I started openly to speak in Norway about my skepticism and critique of the diagnostic system,” Valla said. Connecting with others who shared her views, she was invited to join the International Institute for Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal. At an IIPDW meeting in Gøteborg in September of 2019, she spoke with Robert Whitaker about creating a Mad in Norway page; the very next day, she fired off an email to everyone she knew with sympathetic views. “And I got so many replies, I was high.”

The website launched in December 2019, topped with a logo inspired by Edvard Munch’s The Sun and fueled by a mixed group of editors and contributors from all walks of life. “We have people with lived experience, we have researchers, and we have professionals”—psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses. “We have all of this, from all parts of the system, that come together.”

Among those listed on the editorial team are Grete Johnsen, a nurse and activist with lived experience; Tore Ødegård, who works at a non-medicated hospital unit in Tromsø; and author, composer, and educator Odd Volden. Voices of youth and children are represented by another editor, Anika, who posts their content and is a young person herself. (Mad in Norway also cooperates with The Change Factory, which surveys young people on their experiences.)

Everyone’s a volunteer. Funding is nil, or nearly. Mad in Norway’s recent seminar did receive some aid from We Shall Overcome, the organization founded in 1968 by psych users and survivors. But beyond that, they only receive the usual support (with Internet hosting and editorial resources) that Mad in America makes available to its affiliates.

At some point, Mad in Norway will be applying for “a little bit of state funding” in the hopes of holding more such seminars, although those who lecture at such events “all do it for free. No one has any money. We’re all idealists about this.”

That said, hiring someone part-time would help run the website, which offers an array of content both original and translated: news; articles on the latest studies, composed by a research committee; and an “Expressions” section that features a wide range of personal stories and commentary. In addition, a year ago Valla created a podcast—“which is a very good way to get knowledge out to people. And many people listen to that, and many people find hope.”

Some have urged her to record the podcasts in English—with the aim of reaching a more international audience. But although she appreciates being part of a wider, global community, right now she wants to keep the focus on Norway. Norwegians still need to be persuaded; work still needs to be done. “You need to keep order in your own house,” she said, “before you go out into the world.”

The country has potential, she said, and those little units offering non-medicated care “are just a small part of it. I really believe that Norway can even more be in the forefront—because we have this welfare system, we have these politicians, we have these strong user movements, and we have professionals.”

Reaching out directly to policymakers should help—as it did with Bent Høie, the Norwegian health minister who first instituted the non-medicated directive in late 2015 and pressed for compliance in the months that followed. “The key lies with the politicians, I’m sure—because you have to change the system from the outside. It won’t be changed from the inside.”

That’s her message to others around the world: Get outside the sealed environment of psychiatric care. Train your sights on those in power who can make policy and effect true reform. “If people within the system—if they decide, it won’t happen,” she said. “So you have to have (people) who are responsible from the outside the system to decide and say, ‘We want this.’”

Valla sees the Mad in Norway’s impact—present and future—in terms of that quest to alter the paradigm. Judging from emails they’ve received from professionals and those with lived experience, they’re reaching people.

“I think the impact now is that people are getting some faith back. . . . People are getting some hope, and they are finding each other, and we are building this community of people who want a change. I think we have done that, a little bit. I don’t think necessarily we have changed anything in the system,” she continued. “Not in a profound way, anyway.”

Moving forward, that’s the mission—profound change. In this vision, “When a person is in distress or needs help, then they can very easily—where they live—reach out and get help in this way. Without diagnoses, medication, any of that. . . . So in the long-term, we want to change the whole system.” To that end, “Our ambition this year is to become even more visible, and participate in different things, so that Mad in Norway is a voice—an even stronger voice. We want to be heard. And we want to have a say in how to develop mental health in the future. . . . Because I think, in Norway, people want to listen.”

Many Norwegians, politicians included, can see that the system doesn’t work. They can see more and more money being spent, more and more diagnoses being made, more and more folks on disability. Mad in Norway can map out an alternate way forward, she said—offering something more than criticism of the existing paradigm. They can be a guide for the future.

“If you start doing something good, it will spread all over,” she said. “So that’s what we’re hoping.”

*****

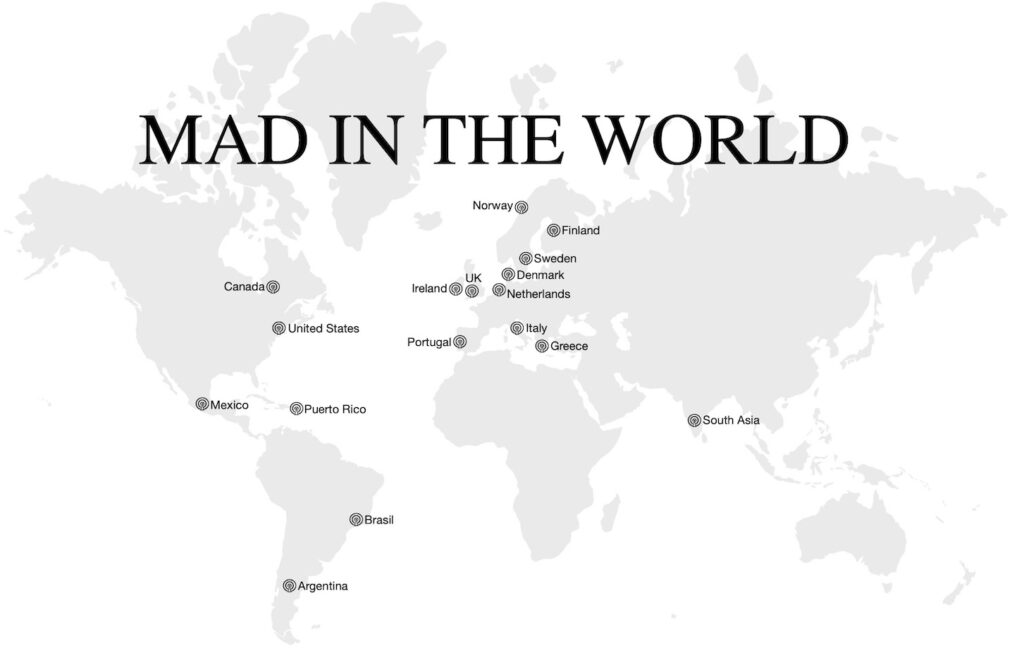

MIA Editors: Over the next 10 weeks, we will be publishing a profile of each of the Mad in America affiliates. They have banded together as a “Mad in the World” network.