Audio: Listen to this report.

The Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center, which is a private psychiatric hospital located about forty minutes north of Oslo, on the banks of stunning Lake Hurdal, was set up by its director, Ole Andreas Underland, to provide “medication-free” care for those who wanted such treatment or who wanted to taper from their psychiatric drugs. Norway’s health minister was urging public mental hospitals to offer such treatment, and this private hospital stepped forward before any public hospital had taken the plunge.

Hurdalsjøen opened on April 1, 2015. The first person to show up at its doors was 31-year-old Tonje Finsås, and she had a medical history that could fill volumes. She had developed an eating disorder when she was eight; she was put on antidepressants at age 11, which is when she started cutting herself; then came a prescription for a benzodiazepine; and soon she was cycling in and out of psychiatric wards with astonishing frequency. She arrived at Hurdalsjøen with prescriptions for 31 medicines, including three antipsychotics, and a record of 220 hospitalizations. She had spent most of the three previous years in isolation at a psychiatric hospital in Bergen, where she was watched over by two aides at all times, and was often restrained in a belt.

“I tried to kill myself every day,” she recalled. “I didn’t want to live anymore. This was not a life. Even a dog in a cage has it better than what you have in there.”

Although Lake Hurdal provides a beautiful setting, the hospital is located in a 1970s building, one that was used to treat people suffering from nervous problems, and inside it has an institutional feeling: small rooms located off a long hallway, not all that different from what you might find in an older psychiatric hospital. When Finsås balked at staying there, Underland proposed a novel solution.

“I had come here right from isolation,” Finsås said. “And Ole starts my journey by sending me to Majorca, Spain for two weeks, with a nurse from the hospital. It was just for us to get to know each other, and for me to get to know a new environment. I see then that they trust me, and when I came back (to Hurdalsjøen), I start to open myself up and tell them things, and I say I want it like this and like that, and they are like ‘okay, we will help you.’ ”

Finsås has never gone back to a regular hospital. In the four years since she came to Hurdalsjøen, she has tapered down to two medications, and now lives in a nearby village. In early September, she began working half-time for the center, directing its activities room, where patients may go to write poetry, draw, knit, or do other such activities, and she is beginning to dream of a career working in healthcare.

“That’s the art of treatment,” Underland said, speaking about the Majorca trip. “You have to find the key for each person.”

A Work in Progress

In public hospitals, the medication-free initiative in Norway started three years ago. The Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center can be seen as both part of that initiative, and distinct from it. But with “medication-free” offerings within the public sector surviving and growing, and the Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center doing so as well, it’s fair to conclude that this type of care is finding a foothold in Norwegian psychiatry, with this initiative attracting international attention.

In the public system, Asgård Hospital in Tromsø was the first to create a medication-free ward, opening in January of 2017. Initially, it struggled to recruit patients, in large part because those seeking this type of care had to obtain a referral from a provider of “specialized health services,” which meant that psychiatrists had to give their approval for “med-free” treatment, something many were loath to do. However, according to Magnus Hald, who was director of Asgård Hospital when the ward first opened and is currently its supervising psychiatrist, the six beds are now regularly filled.

After three years, Hald and the staff at Asgård have seen that the treatment they are providing, with medication use adapted to the needs and wishes of the individual, is proving to be helpful to many. More than 90% of the 50 or so patients who have been treated on the Asgård ward have had a psychotic diagnosis, and about half of these patients have not taken neuroleptics while hospitalized. Contrary to what one might expect given conventional beliefs about the need to prescribe antipsychotics to such patients, many who eschewed the drugs “didn’t seem to have psychotic symptoms” while on the ward. The others in this non-neuroleptic group, while psychotic at times, “are finding new ways to deal with the symptoms,” Hald said.

The Asgård staff also have become more experienced in helping patients who arrive on neuroleptics or other psychiatric drugs taper from these medications or get down to lower doses. “I would have expected it to be difficult, but it has been surprising to me to be able to do it (successfully) much more slowly than I thought, and we have had a few patients who have gone all the way (to no medication) with small steps,” Hald said.

The staff have also seen the benefits that can come from patients getting down to lower doses. The patients “often report that when they taper they get problems back, but they find new ways to deal with them. These people have a very strong feeling about getting their emotions back, and this is also experienced by their families. One woman told us, ‘I thought I lost my husband four years ago, and now he’s back.’”

Early on, there were two or three patients on the medication-free ward who were so challenging that they had to be transferred to the acute wards. But that hasn’t happened in recent times, and during the three years, no staff member has been assaulted, and none of their patients have committed suicide, including following discharge.

The patients typically stay on the ward one to three weeks. Hald and his staff then work with local providers to continue outpatient treatment that is consistent with the “med-free” principles practiced on the ward. This continuity of care also provides a relief valve for patients after they leave the hospital—many discharged patients come back to the ward for a second or third stay, using it as a respite from community stresses. “Many people want to stay in the ward,” Hald said. “Some people like it too much.”

In many ways, the Tromsø ward is creating change in psychiatry much in the manner that a stone dropped into a pond creates an outward ripple of waves. Providers in the community are adapting to the treatment plans prepared by the ward, and there is also growing acceptance for this approach by staff in the rest of Asgård Hospital.

“We have been able to help some patients, and we have been able to address this question of how drugs are being used, getting this on the agenda,” Hald said. “That might be the most important thing we have achieved, is to be part of a movement, nationally and internationally, for this development.”

Although Norway’s “psychiatric establishment” has resisted the initiative, a 2018 review found that all four regional health authorities had, to some degree, complied with this mandate, and that there were now “56 beds in 14 hospitals” in Norway that had been earmarked for medication-free treatment (which means that patients can opt for such care, or get help tapering from medications). In some instances, the hospitals have only set aside a few beds for such care, as opposed to opening a “med-free” ward, and several regional authorities are providing it only for “non-psychotic” patients. However, much like in Tromsø, Akershus University Hospital has opened a ward dedicated to “med-free” treatment, and both hospitals will be conducting research on the longer-term outcomes of their patients.

All of this tells of an initiative that is still very much a “work in progress.” Yet, while the public mental hospitals may be proceeding cautiously, the patient demand for such care is growing at a rapid clip. In a recent survey of 100 patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Norway, 52% stated that they “would have wanted drug-free treatment if it existed.”

The Power of a Graphic

In Norway, the public is accustomed to getting health care through the public system, and thus the Fellesaksjonen of five user groups that spent years lobbying for medication-free treatment never thought that an “entrepreneur” would suddenly appear offering such care. The spark that led to the creation of Hurdalsjøen came at a national mental health conference in 2013, when Jan-Magne Sørensen, the leader of the user group White Eagle, put up a slide that made Underland jump out of his seat.

Underland had a work history that combined years of clinical experience in a psychiatric hospital with success as a business entrepreneur. He began working at Dikemark Psychiatric Hospital in Asker at age 18, and after he got his training as a psychiatric nurse, he rose to chief of staff of the hospital’s maximum-security unit, holding that position from 1988 to 1993. In 1997, after a stint working as a sales rep for Novo Nordisk marketing its antidepressant Seroxat, an experience that taught him “how drugs satisfied the demands of doctors,” he started a private company that provided housing to people with mental and behavioral difficulties. That entrepreneurial venture, which he eventually sold, taught him that “if you give people proper housing, they can live a good life with support.”

In 2007, he purchased the Lake Hurdal site that had once provided care to “nervous” patients, and used it for a variety of rehab and housing purposes, recruiting his longtime friend and fellow psychiatric nurse, Tom Liudalen, to run it. All was proceeding well in his life, he had sold his housing business and was financially secure, and then Sorensen put up a slide—one familiar to readers of Mad in America—that redirected his life.

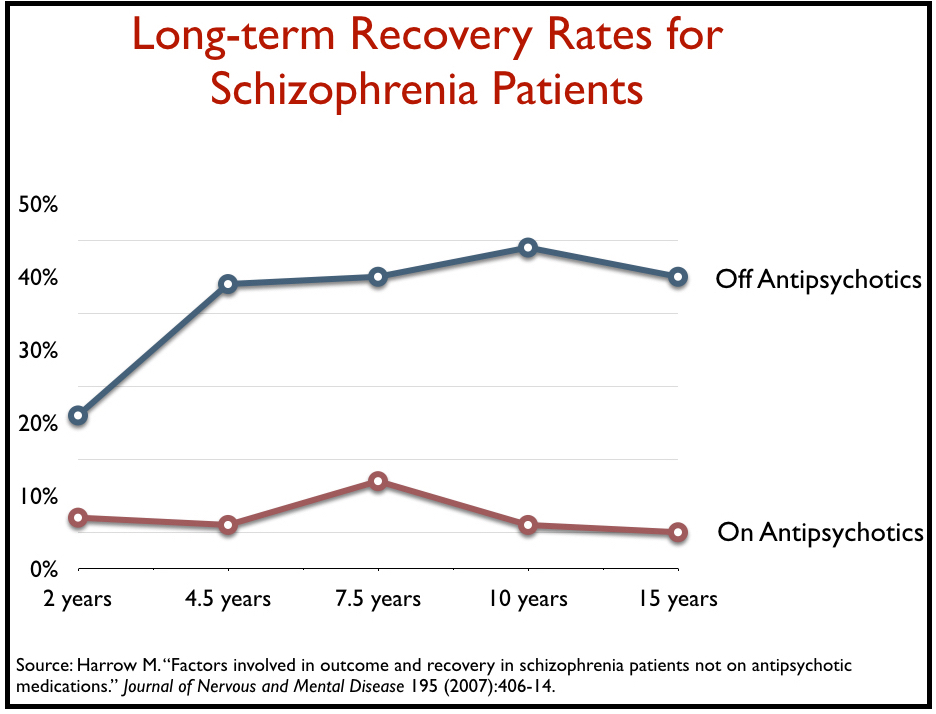

“I am a psychiatric nurse by profession, and I had been working for decades in this field and I had never heard about this, that the long-term recovery rate for patients suffering from schizophrenia was far better without medication than with medication,” Underland said. “I have to admit, I kept thinking this cannot be right.”

“I am a psychiatric nurse by profession, and I had been working for decades in this field and I had never heard about this, that the long-term recovery rate for patients suffering from schizophrenia was far better without medication than with medication,” Underland said. “I have to admit, I kept thinking this cannot be right.”

Underland invited Sørensen to dinner and that led to meetings with the Fellesaksjonen leaders, where he listened to the visions they had for “medication-free” treatment. Although the five user groups had different ideas for what that treatment should be, they eventually settled on several governing principles, beyond that of offering people a “medication-free” choice.

“We said we would like up to 50% of the staff to be users with experience, a minimum of one third. This was a big thing,” said Grete Johnsen, a Fellesaksjonen leader from the We Shall Overcome user group. “We wanted a more holistic, human way of meeting people, where you ask people what their problems are, instead of just diagnosing people. We wanted them to remember to talk to people. And another thing that causes such problems is the journals, what the staff writes about the patients and then the patients read all of the bad things written about them. We wanted the journals to be made together with the patients.”

There were other requests: good nutrition, the chance to be out in nature, and opportunities to exercise, relax, and pursue creative endeavors. “Do everything you can to make good health,” Sørensen said. “Focus on positives that you can build on instead of what is not working.”

With these thoughts in mind, Underland and Liudalen set about creating what they describe as the first “medication-free” psychiatric hospital in Norway and all of Europe. Their missionary fever for this task was due, in part, because they had become convinced that psychiatric medications, when used as the cornerstone of care, have negative long-term effects.

Liudalen’s experience with psychiatric hospitals began when he was a child. His father had worked on the farm at Dikemark, while his mother had worked inside the asylum. “As a kid, many of the patients were our friends,” he recalled. “They joined us for activities.”

After training as a psychiatric nurse, Liudalen went to work at Dikemark, and what he came to understand was that asylum doctors would prescribe drugs to satisfy their own feelings and needs. “It’s clear to me that we can’t think that way any longer,” he said. “We’re giving too much power to doctors, and medication is part of their work. This is where things start to go wrong. We get new medications, and if one doesn’t work, we add another. This is not good for the patient. It all goes worse and worse.”

Underland, in a public presentation, echoed this thought. “The treatment we have used since the 1950s has been medication, and it has proven wrong,” he said. “We spend more and more money on medication, and yet there is the continued growth of mental disorders. Relying on medication obviously doesn’t work.”

As they opened Hurdalsjøen Recovery Center on April 1, 2015, they had one overriding hope. “I want to make the first psychiatric hospital that I could be a patient in myself,” Underland said.

Visiting the Center

This past summer, Hurdalsjøen opened a second “hospital,” located a few kilometers away from the first, and this setting, also on the banks of Lake Hurdal, is where the center’s ambitions are most visibly on display. The facilities here were previously home to a summer camp, with cabins for visitors and a beautiful lodge stretching out along the lake, the water so close that when windows are open you can hear the lapping of the water.

Being in nature is part of the “treatment” plan at Hurdalsjøen, and here you find canoes resting by the lake, a nearby fire-pit where at night the stars light up the sky, and a forested hillside that patients “run up” as part of their daily exercises. The lodge is a spacious, warm place, with a large common room warmed by a fireplace off in one wing of the building and a communal dining hall in the middle. The dining hall features a bank of windows looking out over the lake and long wooden tables where staff and patients eat together. The meals, which are served buffet style at several food stations, provide a diet of fresh fruit, vegetables, baked breads, soups, salads, and entrees of the day.

I spent two days at the center in early October, and the dining hall was my favorite space. There was always a sense of comfort and warmth present, with people coming early before meal times to sit at the tables and talk, and then staying after the food had been finished. For the most part, it wasn’t apparent who were staff and who were patients, and it was only after I had spoken to those at my table that I came to know their individual stories.

“I like the mix,” said Siv Helen Rydheim, one of the Fellesaksjonen leaders who lobbied for medication-free treatment and now works half-time at Hurdalsjøen. “I get in touch with both staff and patients in an atmosphere where I find it easy to make contact . . . I don’t think it could happen so quickly without having these meals together.”

The communal meals, of course, also diminish the presence of the usual power structure present in psychiatric hospitals that draw a line between “staff” and “patients.” The mealtime conversations help create relationships that can be so transformative for patients, and, at the same time, provide the staff with helpful feedback.

“Most of the patients feel free to give feedback on both what can be done better and what they are satisfied with,” Rydheim said. “And one of the things I really like about the center is that when things are not going exactly as we think they should, the staff and the leaders make an effort to change things.”

The chance to be outside in nature, the daily exercise, the fresh food, and the social dining hours are all seen by Underland, Liudalen and staff as promoting “salutogenesis.” They want to provide care that supports physical health and emotional well-being, as opposed to treatment that focuses on knocking down the symptoms of a disease (pathogenesis).

The two “hospitals” have beds for 60 patients, with most coming for treatment that lasts four to six months. Reducing psychiatric medications during this time, or treating patients without their use, is understood to be consistent with this philosophy of salutogenesis.

Medication

When Mohammad Yousaf was 11 years old, a relative of his who didn’t speak Norwegian—his parents had immigrated to Norway from Pakistan—had a manic episode, and he became the translator for the psychiatrist. That experience led him to become a psychiatrist, and deeply influences his thinking today.

“This psychiatrist didn’t work in a regular way,” he recalled. “He was open to different ideas, and in this family of my relatives, in their background, you don’t have this psychiatric understanding (of manic behavior). You have a cultural focus and a family-oriented view on how to get better.”

Even so, he was inducted into conventional Western thinking while at medical school in Oslo. “I got the conventional biological training. I understood that drugs were the first-line therapies, particularly for psychosis and bipolar. And that’s how I practiced, at two of the biggest hospitals in Oslo.”

During those first years of practice, he began to question this reliance on drugs. “I am seeing that, yes, the medication sedated people, made them more malleable, and more controlled, but I didn’t see any recovery,” he recalled. “I am seeing my patients coming back. And they often didn’t want the medication, that was strange for me, because usually if medication is helpful, patients want the medication. And so that was strange, and the recurrent admissions also made me wonder if this is the right way to go.”

With his skepticism growing, he became more alert to the metabolic dysfunction and other adverse effects caused by the drugs. Then, as the medication-free lobbying efforts by the Fellesaksjonen gained momentum, he attended a conference where service users and others spoke about why this was needed.

“I went there and was surprised by how many of them had experienced these effects, and how big of an issue this was—the resistance to take medication, the bad experiences. And lots of people (at the conference) had relatives using these medications, and they told how their relatives didn’t get better, but rather, to the contrary, they got worse, they got more ill.”

The final bit of evidence that changed Yousaf’s thinking about psychiatric medications were long-term studies, such as the one by Martin Harrow that found higher recovery rates for schizophrenia patients off medication than for those who reliably took the drugs. “This made me aware there is another truth out there,” he said.

There have been slightly more than 100 patients come to Hurdalsjøen since it opened, and fewer than 10% have been off medication when they arrived. None have been medication naïve, and polypharmacy is common. As such, in this “medication-free” center, drug-tapering is the treatment of choice.

“Before the patients come here, they know about our treatment and our offering,” Yousaf said. “I don’t have to bring up the medication issue, it’s the first thing they bring up. The major work for me is to get them to trust me that we will help them, that I will help, and about different aspects of why time (a slow tapering) is important.”

As a first step, he takes a “full history” of their use of psychiatric medications and what side effects they have experienced. Usually, he said, “there is one medication they want to get off first.” The customary tapering process involves tapering one drug at a time, and if a patient is taking a benzodiazepine, Yousaf leaves that for last, as that drug can be helpful for easing withdrawal symptoms from other medications.

The four to six months that patients stay here is a fairly short time for tapering from a drug cocktail, Yousaf acknowledged. “One thing that is really constant with all patients is that you need time. So even though it is very individual in regard to how bad the tapering symptoms are, you need time. For some the physical symptoms are much worse than the psychological, and for some it’s the other way around. Either way they need time.”

One patient I spoke to at Hurdalsjøen, Siri Westerås, had come here after having been on Zyprexa and Effexor for two years, which caused her heart problems, sexual dysfunction and other adverse effects. She had tried withdrawing from the drugs on her own, but that had gone badly. And, she said, the tapering program she was following at Hurdalsjøen was proving to be difficult.

“I feel numb. I can’t feel right. I can’t even feel really now. My body responds, but my head doesn’t,” she said.

Still, she found reason to be encouraged. “I feel that people here see me and listen to me. Here I am not only my depression. When I was hospitalized two years ago, they treated me like I was demented.”

Yousaf said that approximately 75% of the patients at Hurdalsjøen have sought to taper from their prescribed drugs, and of those that have, “five of every six” have met their goals. Some have gotten all the way off the drugs, while others, once they are down to lower doses, say they are satisfied.

“Almost none of the patients want to leave before four months, and most want a little bit more time,” he said. “And the prospect of going back to a system that maybe doesn’t respect their wishes is scary.”

Illness Management and Recovery

Although Hurdalsjøen is intent on creating an environment that is radically different from conventional hospital care, the therapy practiced here, illness management and recovery (IMR), is imported from the United States. At first glance, it seems at odds with the philosophy and beliefs that are so evident in everyday operations at Hurdalsjøen, for it is an approach—even as described by Kristine Omvik Bråten, who helps lead the IMR program—that fits within a “disease model” understanding of psychiatric difficulties.

IMR, Bråten said, helps people develop strategies for coping with their “mental illness” and moving forward in life.

Yet, at Hurdalsjøen, IMR is seen as a process for helping people transform their lives, away from their previous lives as mental patients and toward a return to an “ordinary” life, living and working in the community. “The most important thing for what we do is to see this (transformation) come true,” Underland said.

All of the patients at Hurdalsjøen are given an IMR manual that has been translated into Norwegian, and five days a week, for an hour each day, they gather in eight-person groups to work on one of the “11 steps to recovery” described in the manual. The first step may be the most important one.

“We will ask each person, ‘what do you want, and what changes do you need to make in your life to get a life you think is good?’” Bråten said. “What people answer to us is very individual. We want them to set personal goals. That is the foundation for the rest of IMR.”

The patients often state they want to get off the drugs. Many talk about wanting to build social lives, or to “get a girlfriend,” said Ann Helen Martinsen, who helps lead the IMR program. “Most of the patients in psychiatry have those challenges. They have a small network, they have a broken relationship with family members, no friends, no girlfriends. They miss the intimacy.”

In the group meetings, Martinsen and Bråten, both of whom have their own “lived experience,” will help patients improve their social skills and instill in them the confidence to try these skills in the “outside” world. “We may talk about how you have to go out and expose yourself to social situations and go to places where there are a lot of people,” Martinsen said. “We can also sit down and make a Tinder profile with a patient if that is what the patient wants.”

It takes about 14 weeks to complete the 11 steps in the IMR manual. During this process, the patients learn about the importance of exercise and diet, how to cook healthy meals, and how to avoid relapse, with this last IMR module adapted for those who have successfully stopped taking medication or having gotten down to a low dose. If a patient has spoken about wanting to get a job, the IMR leaders will help them develop a plan for doing so. They will also drive them to a job interview.

“On Friday, we have a goal day where we specifically talk about the goals that patients have set for themselves,” Bråten said. “It doesn’t have to be about their psychiatric health. It can be more specific, about practical things, like going to that interview for a job. And on Fridays we go around and applaud each other for everything they have done, for reaching goals.”

The familiarity—and spirit of friendliness—that is present at Hurdalsjøen raises an obvious question. In psychiatric hospitals in Norway, there is a prohibition against “hugging” patients, and so I wondered, was this a boundary line observed here?

“We have moved from being very professional as health care makers to where we give the hugs to have the good conversation,” Martinsen said. “Because they are patients, they are people, just like me and everyone else. They need the hug. If they have had ten years locked up in a psych ward, they have never had the hug or just a long good talk. Of course, all people need that type of care and human contact . . . the patients here say it is so different, the way we connect and have contact with the patients. We see them and give them the hug when they need it.”

Added Bråten: “I think it is very important to have guidance about this with the staff, and talk about where the boundary goes. Maybe it isn’t always about hugging. It’s about the warmth we can give with the words, the eye contact, the small things.”

Underland and the rest of the Hurdalsjøen leadership see IMR as an essential tool for helping patients transform their lives. “We see how the people feel more successful when they are ready to leave,” Martinsen said. “We see how far the patients have come from when they first arrived. When they leave, they can be totally different persons.”

Recovery Pilots

In a conventional psychiatric hospital, the usual goal is to help people get “stabilized” on psychiatric medications, with the thought that discharged patients, with regular use of the drugs, can be in “recovery” from the illness. The drugs help keep the “chronic illness” at bay.

At Hurdalsjøen, a trajectory of a different sort is envisioned. The patients who come here are expected to imagine a different future for themselves, and a little more than a year ago, the center established a “recovery pilot” program to help patients transition into new roles, in which they assume work responsibilities and serve as mentors—e.g. as recovery pilots—to newly arriving patients.

“They have all been patients before they became recovery pilots, and they have all been outside work for a long time,” said Tone Winnem, who directs the program. “They may not have an education, and they have been traumatized in (psychiatric) hospitals before, and they have no trust for people. So after their work as patients here, we want them to work in a way that will help them find meaning and gain a meaningful life. They use their experience to motivate the other patients here.”

Said Underland: “We believe having a job is the single most important factor in every person’s life.”

Like many of the staff at Hurdalsjøen, Winnem can tell of her own transformed life. As a child, she heard voices and worried that if she told anyone about her voices they would think she was “mad” and that she would be put in a mental hospital. This was the secret she kept to herself, and as she grew up she suffered from repeated bouts of depression and suicidal thoughts. “I had a long history of mental illness,” she recalled.

Her life changed after she attended an IMR program in her hometown of Eidsvoll. “I set a personal goal where I wanted to live out my dreams to be an actor. So I went to a local theater group, wrote a standup comedy show, where I told of my experience of hearing voices. One of my voices had always said to me, you are not allowed to tell other people about me. But when you go and do a standup show, you have to tell all the people about this, and after doing the show, the voices slowly became weaker and then finally the voices were gone.”

Winnem then traveled around Norway speaking about how IMR changed her life, and when Underland heard one of her presentations, he hired her to start the recovery pilot program. Much like the recovery pilots she now supervises, she is newly experiencing what it is like to live without the emotional dampening of psychiatric drugs. After she came to work here, Yousaf helped her withdraw from the two psychiatric medications she was on, one of which was an antipsychotic. Six months ago she became “medication free.”

“I am happier,” she said. “I feel like I can be alive all day. I can control my life in a better way. And I can feel both sadness and happiness. When I am on the drugs, I feel very flat.”

Since the recovery pilot program was started, seven patients have become recovery pilots. I spoke with four of them.

Eirik Andres Øyen

The morning I arrived at Hurdalsjøen, I was put under the care of Eirik Andres Øyen. He showed me around the hospital, known as Haraldvangen, that had opened earlier that summer, taking me to where the canoes were, pointing out the fire pit where people would gather, and taking me on a tour of the nearby cabins, one of which he lived in. During my two days there, he often stopped to ask how I was doing, and whether I needed anything. This, I came to understand, was all part of his recovery pilot work.

“He is chief of reception when families and visitors come,” explained Winnem. “And when patients go home and have to return their keys, he is responsible for that. He is the master of the hotel.”

Before coming to Hurdalsjøen, Øyen had been on a forced treatment order for seven years, and during that time he had repeatedly tried to run away from Norway’s psychiatric system. Thirty years old, he had worked on large fishing boats after finishing school, spending six, seven weeks each time at sea. But he partied hard whenever he returned home, regularly using amphetamines, hash and other drugs, which triggered psychotic episodes, and that led to several hospitalizations and regular injection of risperidone.

“I didn’t like the injections. I had to lay down and put out my ass and I had to do it every week or every second week,” he said.

Twice he fled Norway to escape such treatment, once to Spain and later to Denmark. Each time, he was brought back to Norway, where the forced injections would resume. He successfully petitioned to come to Hurdalsjøen in June of 2018, but arrived under a forced treatment order, which required him to take Risperdal orally each morning and night. Six months later, Yousaf got the forced treatment order lifted. “I became free,” he said.

Øyen became a recovery pilot in the spring of 2019. “I like the work, and arranging things for others. When I am a receptionist, I feel like I have something to do. It gives me meaning.”

He still takes a low dose of Seroquel in the morning and a low dose of Risperdal at night, a drug regimen he finds helpful for now. He hopes to eventually work in a hospitality job in the community, but for now is in no hurry to leave Hurdalsjøen.

“In all the other (hospitals), it was, ‘when can I get out, let me go.’ Here it feels more like home. They ask you what would you like to do, what can you do, instead of you have to do this, you can’t do this. You can feel you want to be here. They treat you like you are a person here, not like you are a diagnosis.”

William Liknes

When William Liknes arrived at Hurdalsjøen in June 2017, he weighed 300 pounds and gasped for breath with nearly every step he took. For the previous several years, he had spent much of his time lying on a couch, doing nothing.

Today, he weighs 210 pounds, directs the daily exercise sessions at the second Hurdalsjøen center, and runs marathons.

The story of his path to Hurdalsjøen is a familiar one. As a child growing up in Karmøy, he was picked on because of his weight and that led to his always “feeling out of place” in social settings. His self-esteem was poor, he struggled with anxiety, and starting when he was 13 years old, he found relief in alcohol. “I could speak up for myself. I could have conversations,” he said.

But anxiety and depression returned whenever he wasn’t drinking, and soon he was taking a mix of psychiatric drugs and illegal drugs, and once he quit school, he began regularly cycling in and out of rehab—a total of 30 times by his count. By the time he was thirty, his drinking and drug problems made it impossible for him to work on fishing boats, and after that he pretty much retired to the couch. Even when family came, he wouldn’t budge. “I was just living day by day,” he said. “I didn’t do anything.”

Two years ago, he went to see a psychologist, hoping to get prescriptions for stimulants and anti-anxiety drugs, but the psychologist, knowing of his drug habit, suggested instead that he go to Hurdalsjøen. This time something clicked for Liknes.

“I’ve been in and out of treatment so many times I just decided to go all in and get off the medication before I came here,” he said. “It was tough, but at the same time, I started feeling again. Before everything was so flat, so even if now the feelings were not so good, or even if they were bad, still I had a feeling. I was happy to rediscover I could have feelings.”

However, when he first came to Hurdalsjøen, “I was so afraid. I was scared of the people, and I thought, ‘everything is new, is this going to work?’ But I immediately felt the peace and calm the way people are here, and the very first day, what they said to me was ‘we never give up. We’ll be with you until are better.’ They gave me hope. I went to my room that night and I felt this very good feeling, that this might work, I might have a chance. That was a feeling I’d never had before.”

The IMR sessions, he said, helped him gain the confidence “to say more and expose myself more.” But the most important part of the program “was the physical training and the food. That was the start of my recovery. It was very hard at first, running up and down the hill, it was exhausting. But I did it, and I did it every day, and I started losing weight. I started seeing more possibilities.”

In October of 2018, he became a “recovery pilot,” helping to lead the exercise program. Now he is employed full-time at the center. Every weekday at 1, he leads the patients at Haraldvangen on their runs, which are done in four-by-four interval fashion: four runs of four minutes each, with rests in between. Those who can’t run, can walk, much as he had to do when he first arrived.

He is now physically fit, and with his newfound confidence, he downloaded Tinder onto his phone, and regularly meets women that way. His goal in life is to start up a day center in his hometown that offers a combination of IMR and physical training to young people before their “problems develop too far.”

“I hope I can inspire the others (at Hurdalsjøen),” he said. “When I talk about myself and my history, maybe they can see that there is hope for them.”

Maria Totlandsdal

The Fellowship, when it lobbied for “medication free” treatment, wanted to provide an alternative to the forced treatment that is commonplace in Norway’s psychiatric hospitals. Maria Totlandsdal, who started cutting herself when she was 13, was first forcibly treated at age 15 with an injection of haloperidol.

“I felt like I was raped mentally and physically,” she said. “They took my jeans down and held me to the floor. But I was most scared by the effect of the medication. I couldn’t move my neck. I couldn’t speak. And I couldn’t tell anybody what was happening.”

Thus began her life as a chronic mental patient. Over the next twenty-plus years, she was hospitalized more than 100 times, and regularly was forcibly treated with the very drugs she hated. Early on, she fled the country to escape the long arm of psychiatry. “I feel like a normal person off drugs,” she said. “I went to school and was functioning okay on every level, they forgot about me for a while, and then I ran from Norway. I go to Sweden, I go to Germany.”

In November 2018, a doctor she was seeing on an outpatient basis “fought for me and helped me to come to this place,” she said. Yousaf has helped her slowly taper from Zyprexa, and after six months as a patient, she graduated to “recovery pilot” status and now helps with housekeeping duties.

“I do cleaning, and I talk to people around me and try to support them,” she said. “I do the (exercise) training to build myself up. Before I came, I had trouble with my heart. But now I don’t feel this problem, and I start to get muscles. I get more energy. I have friends here, my colleagues.”

The worry for her now is that she needs to prepare to leave Hurdalsjøen. “I don’t want to leave. I feel safe for the first time in my life. I feel included. I feel welcome. But my mission now as a recovery pilot is to get back to society. I don’t know how, but I will try to be part of the community.”

Tonje Finsås

Thanks to her extraordinary story of transformation, Tonje Finsås has become, in Norwegian media, something of the “poster child” for success at a “medication-free” facility. And while she credits all aspects of the center’s program for her new life—“I went through IMR six times,” she said—her gradual withdrawal from psychiatric drugs is what made it possible, for it allowed her to regain an emotional self.

“When the medication starts to come off, I start to connect with my feelings again,” she said. “I was never happy before. I was never sad. I didn’t feel anything. I remember the first time I cried because I felt happy. Something on the TV really touched me, I got emotional, I could feel! I wrote a poem: ‘I smile because I am happy, and not because others are smiling. I laugh because I want to laugh because I think something is funny, and not because others are laughing’ . . . that was what I wrote in my poem.”

The withdrawal process has been difficult, she said. She has had hallucinations, physical pain, and felt extremely angry for all that was done to her in her many psychiatric hospitalizations. But the return of her feelings has enabled her to build a social life, make new friends, and restart a life with her parents.

“I feel like my parents actually love me and I am not just a burden anymore. My Dad says, ‘I love you, I really love you,’ and before, I would think, ‘how can you love me when I am just a problem?’ But now I think, yeah, maybe he really loves me.”

She started working half-time in September, directing the activities room, and will go full-time on January 1. “This makes me feel very good,” she said. “People give me credit and show that they trust me and they tell me their stories. They say, ‘it’s just you who really understands this’ and that ‘nobody understands me like you do.’”

Serving as an example for others, she said, is the most important part of her work as a recovery pilot. “My story shows it is possible to get better. It is possible to get back out there. Yes, I am high and low still, but I control it, I know what triggers it, and I know what to do . . . Without Ole and Yousaf, I wouldn’t be alive today.”

Family

While the recovery pilots serve as Hurdalsjøen success stories, they don’t represent the experiences of all patients. Many patients continue to struggle with anxiety, depression, psychotic symptoms and behavioral difficulties, and even if they have gotten better while here, they may struggle anew once they return to their home communities.

Such as been the case with Solrun Elisabeth Steffensen’s 40-year-old son. Like many of the patients at Hurdalsjøen, her son had a long record of forced hospitalizations before he came here for the first time, and while he got better during that stay, when he returned home to Trondheim, “everything started falling apart,” Steffensen said. Her son ended up back in a psychiatric hospital, and once more subjected to forced treatment.

Her son is now back at Hurdalsjøen, and once more doing better. “I feel like relatives and family are taken seriously here. I experience real cooperation, and they listen to both me and my son’s own knowledge and expertise about his life situation,” she said. “All the people working here contribute to this. It’s as if their motto that ‘there is hope for everyone’ permeates the entire organization and sits in the walls.”

A Blueprint for the Future

Together, the ward at Tromsø and Hurdalsjøen are proving that it is possible to provide psychiatric patients with hospital care that allows them to decide whether to take psychiatric drugs and provides support for those who want to taper from the drugs. Both facilities report having fewer difficulties with patients treated this way, with aggressive acts by patients less common than in conventional hospitals, and the success stories of the recovery pilots tell of how such care, at least in many instances, may help “chronic” patients transform their lives.

“We had to learn to treat people in this way who, we were told, were too difficult, too cognitively dysfunctional, and too ill, and we saw it was possible to work in this way,” Liudalen said.

Added Underland: “We experienced how powerful it was to ask them what are your likes and your goals, and to respond to that. We learned how important it was to listen to their opinions about medication.”

The most pressing problem for the center today is trying to survive as a private hospital in a country with a public health system. Although Norway is a rich country, with many families having the financial means to send a family member to Hurdalsjøen, there is a cultural belief in Norway that “everyone should be treated in the same way, and thus to pay for this kind of treatment is unswallowable today,” Underland said. There have been patients come from other countries, but most have come through referrals from the public system in Norway, which puts Hurdalsjøen into the same difficult position as the Tromsø ward, only more so.

Under Norwegian law, patients have a right to choose their hospital, and that right extends to Hurdalsjøen, as it is a licensed psychiatric hospital. However, as noted earlier, patients must get a referral from a specialized health provider, which is generally the psychiatrist and hospital currently treating them. Leading psychiatrists in Norway have stated that treating psychotic patients and others who are severely ill without antipsychotics is “malpractice,” and thus many specialized providers won’t refer for that reason. In addition, if a patient is transferred to Hurdalsjøen, the Norwegian government will pay Hurdalsjøen for that patient, but it then bills the regional provider for this cost, which provides a financial reason for the regional provider to not make the referral in the first place. “Patients and their families tell us every week they have to fight to get here,” Liudalen said.

Hurdalsjøen, with a 60-bed capacity at the two sites, was less than half full when I was there in early October, and this clearly puts financial pressures on Incita, which is the company, owned by Underland and five other Hurdalsjøen employees, that runs the hospital. He and Liudalen have thought about turning Hurdalsjøen into a public hospital, but doing so would require operating within a stricter set of guidelines than they do now as a private one. For instance, they would have to give patients a diagnosis in order to be in accord with that public system, yet that is not something they want to do.

“The problem with diagnosis is it takes responsibility for your life away from you,” Underland said. “What the heck are you going to do with a diagnosis other than get drugs, or use it as a reason for being like you are (e.g. a mental patient)?”

While finances are an obvious concern, Underland and Liudalen are not letting that worry stifle their plans for the future. They have already set up a “recovery village” comprised of 15 houses near the hospital, which can serve as transition housing for patients who have completed a stay at Hurdalsjøen and wish to remain nearby. They envision creating a program, built on the principles governing Hurdalsjøen, for teenagers struggling with problems, with this effort designed to prevent these youth from “being given psychoactive drugs and turned into patients who aren’t able to live and to work,” Underland said. They also hope one day to open “medication-free” hospitals modeled after Hurdalsjøen in other regions of Norway and in other countries, with Switzerland, Holland and Germany seen as the likely candidates for this expansion.

More immediately, they are planning to raze the first hospital and replace it with a facility that will provide each patient with a private room designed to bring light and nature into their living environment, and with a layout that will require the patients to get their steps in as they move about. The main building and the cabins will be built with wood from nearby forests, and the overall design will provide spaces for people to socialize and to be alone with their thoughts, with nature—the lake, a clearing, paths in the forest, and a nearby creek—everywhere present.

“Nature,” said architect Ola Roald, “is a gift for having a good life.”

Feedback from the Fellesaksjonen

At the end of my second day at Hurdalsjøen, I met with four of the Fellesaksjonen leaders. While they did raise questions about some aspects of Hurdalsjøen, they see it as the hospital that best embodies the model of care they had in mind when they launched their medication-free initiative.

The biggest problem, they said, was that it was very difficult for patients to get approval to come here. Several times, Johnsen has engaged attorneys to help patients in public hospitals get a referral to Hurdalsjøen, with these legal actions taking months before they produced a decision. When I was there, one of the patients was a journalist who is a member of We Shall Overcome, and she had needed to wage a fierce struggle, with Johnsen’s aid, to come to Hurdalsjøen instead of going to a public hospital. “This is something we are working on. Making it easier to get here is one of our goals for next year,” Johnsen said.

As for Hurdalsjøen’s operations, the four Fellesaksjonen leaders—Johnsen, Sørensen, Hildegun Flatabø, and Irene Svendsen—spoke of wanting to regain the same level of input that the user groups had when Underland first met with them six years earlier. At that time, Underland had offered the user groups the opportunity to become part owners of the hospital, but because of differences between the user groups, they were unable to take him up on that offer, and their input after that waned.

The most challenging aspect of creating a radically different “hospital,” the four said, was that unless staff had lived experience, most came to Hurdalsjøen after working in conventional settings, and it was a challenge for them to “switch their thinking” and work in a new way. However, Johnsen added, many of the staff coming now are doing so because they want to work in a non-traditional way, and that was “making it possible for it to be the place it is supposed to be.”

Mostly they had other small criticisms. The food here is good, but patients are allowed to eat in their rooms, with sodas and sugary treats they have bought outside the hospital regular fare, which is short-circuiting some of the benefits of a good diet, they said. Several thought that the emphasis on IMR created an overly regimented therapeutic environment. Flatabø said the hospital should provide better training and education to the recovery pilots; Irene Svendsen wished they would incorporate open-dialogue practices into their program, particularly for purposes of family therapy. Sørensen stated that there should be a greater understanding by the staff that going through a psychotic episode without the use of medication could be a helpful experience, as that had been the case for him.

But all agreed that patients at Hurdalsjøen were, by and large, faring well. “Many people have had some good success,” Sørensen said. “It’s not everyone of course being satisfied, but many patients have a success story from this place.”

Apple Trees

As this second day drew to a close, we all gathered by the lake and looked back uphill at where the new hospital would be built. Grete Johnsen and Jan-Magne Sørensen were each asked to plant an apple sapling, for it was the user groups who had inspired Hurdalsjøen. I was asked to plant a third, and as this moment passed, Underland’s words from earlier in the day captured the spirit of the moment.

“We have made our choice,” he said. “This is going to be the most important psychiatric hospital that is making this revolution happen. We will show it can be done, and then the revolution will have to happen.”

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Existence is chaos. We are just trying to hang on. Putting up blinders so to speak, to comfort us from our fears. Life is fragile, it could break at any moment, for anyone or anything.

Report comment

And on another note, so to speak, Maria’s fortitude is incredible. I can only imagine the horrors she experienced, as her experience was not mine. Why is often a bad place to start, but why do only some people have the might to persevere regardless of suffering and the overwhelming reality that this could all end in an instant. To face that fear, I believe, or rather attest to, is something you are forced to do when the shit hits the fan so to speak. There is no other way. Tread carefully, it all begins with safety.

Report comment

Sorry I did not read the whole story yet, and I’m sure I will find something to nitpik on, but on first glance how much I LOVE the story of Tonje.

I want to go back in time and have someone to take me somewhere. Without reading the article, I am hoping that at this temporary home, not only can you taper from meds, but also first and foremost drop the labels.

I’m sure Tonje had a bunch. She was lucky being one of the young, since for many antipsychotics take a bit of time before frying the brain.

These kinds of places should be mandatory and WITHOUT labels.

And they should be the same size as other psych units, so to accommodate whoever so chooses. If there was a choice of label or not, meds or not, I wonder where most people would go to?

The ONLY reason people have ever gone to a shrink is because there are no choices.

So Norway, why not become a WORLD LEADER and go big. Don’t use a mandatory DSM. It is doable, don’t fall for propaganda and habits.

The rest of the world would not like it, they would point to every ‘failure’, every crime as some kind of proof.

But all that would ever be is an attempt to shut down systems that are helpful for the majority, not the minority.

Why not be radical? Why not be the leader that causes other countries to have their peasants question the system and put pressure on governments.

I am sincerely hoping that Norway is not busy hiding psych crimes through a six bed unit, in essence using the ‘sick’.

Because Norway has been busy using force in regular hospitals. Hopefully that could be eradicated. I doubt people are looking for a tiny alternative within a huge slop pail.

Report comment

Way to go Norway! This is really good news.

Report comment

With a bit of luck it will take off!

Report comment

Editors , This is what I Pat H. E. do to maintain my focus and moving further in my life goals. This is participating in Zumba at local Ymca. They filmed a video to showcase their new downtown location. I’m satisfied but they didn’t get my best moves. https://youtu.be/c4nc2vHxpMI

Report comment

Some parents I know in the USA are seeking alternative options like the hospital described in this article because they support their loved ones desire to live a drug free lifestyle but want a safe and supportive place to optimize their loved one chances of success during the tapering process. Medical tourism may be the only solution for some families in the USA as long as psych drug withdrawal is not viewed by mainstream psychiatry as a serious option for people who have been involved in the mental health system for years.

Report comment

Medical Tourism is what it’s probably going to be at the start; but maybe cheaper than at home!

I’d imagine lots of successful variations will eventually develop, as the users help each other.

Report comment

Now all we need is a genuine disease to treat.

Report comment

How about the disease of “Non Existent Severe Mental Illness”.

Report comment

What a thoughtful, thorough, and humane article. Bob Whitaker writes with a sensitivity for the perils of antipsychotics though he’s probably never been on them.

As someone who has experienced the full force and brunt of the American system, my first emotion is jealousy: why not me? Why did I have to endure this absurd treatment regimen? Seroquel, abilify, zyprexa, lithium, haldol….. I’ve been on all of these. How dangerous!! Thanks Bob well done.

Report comment

Randall, exactly, I’m sure many people are saying “why not me” or why not my child. I am working my way through Anatomy of an Epidemic and just read about ‘Jasmine’ on page 248- 251 and nearly cried over her plight. I am sure Jasmine’s mother and very many others feel the same.

Report comment

My first post was made before reading the whole article.

After reading it all, I am glad to see that there are also med free beds in public hospitals.

Psychiatry is somewhat co-operating in Norway.

Robert I am so glad you went there, and reported back. We all hope that other countries will follow.

We know psychiatry does not want change, and we wonder why exactly that would be? We don’t want to give all humans the chances they deserve? That thinking is based on coming from a privileged background and enforcing your idealogy upon those less privileged. It is punishing people for being different, which you call sick. If someone had 20 years of negative experience, why would you add a bad label, dulling or anxiety, brain frying drugs, take away liberty on every level? How is that not abuse?

It would instead perhaps take another 20 years to show a person that their life has/had meaning, that they deserve, just as the psychiatrist does, freedom and safety.

I don’t blame the patients for wanting to come back. Stuff takes a while to recover from, adjust to, to put up with.

I love the fact that there is continuing care and hopefully no one is seen as a failure or feels like one.

It would be great if the patients were also offered to accept or reject the labels, in a legal manner.

People are not their labels, why give them labels.

So Go Norway! Thanks for spreading the news Robert. Hopefully all of Europe will want to be in on this novel and sane approach.

Report comment

As long as people are taught to identify as “patients” in “hospitals” this is more of the same old wine in a slightly different container. Psychiatry cannot be “reformed,” it must be abolished.

Report comment

Oldhead, I carefully worded my first response, because I did not feel like leaving a ‘negative’ comment. Of course it’s my fear that The labels, that view of damaged, needy people exists within the walls. That the only difference is the choice of medication.

And thus, places like this bring out that old familiar feeling of “yeah sure, but not good enough”

Yet, I am thinking of the people that flock to this new age house. And I’m hoping that it is a step for them to transition to their own conclusions about psychiatry. They obviously don’t believe medicine is the answer, which is a step, to visibly make a statement to big pharm and psychiatry. And it is why I asked if this new house/trial, also is able to drop labels as that is foremost to change.

And also, if the “patients” ‘don’t succeed, is that seen as failure by the “patients”? My fear is that yes, that will be the prevailing view. And then what?

Back to meds?

I am very afraid that it is an “adjustment house”, where you can learn to be off meds and learn to live with your “disease” in a caring way, having to show and prove that you can live ‘successfully’, according to society.

It is difficult when I see something like this crop up, to find the positives amid a system that clings to that DSM bible. I find it demeaning in many ways and I bet in some ways, so do those “patients”. It is the forever paternalizing manner, the view staunchly held that they hold the answers as to what and how people should be. I would like a house where people are taught that they are NOT MI, just because they have difficulty ‘adjusting’ to a certain system.

The fact remains people do in fact need help, and psychiatry calls that an MI. I don’t much care for the word “disabled” within the world of the blind, deaf, people paralyzed, yet in many areas they need help.

When differences within society are named a “disability” it is done so with the view that these people do not measure up to what society expects from them.

Report comment

We all need help dealing with this system till we succeed in casting it off. But to identify some as “special cases” when it’s really a continuum of misery/alienation is missing the big picture. To be consistent we would need “beds” for billions if we focus on combating the results of oppression rather than the forces which perpetrate it.

Btw these are not critical responses to anything you’ve said; I’m just thinking out loud.

Report comment

To help clarify my statement a little further, there are likely infinite ways to “help” people on an individual level to “get through the night,” literally and metaphorically. But when the culture is designed to stifle human aspirations in the name of corporate profit there’s no way to eliminate the constant supply of people who need “help.” So to take a toxic culture as the norm against which all human activity is measured, and treat individuals’ deviations from and reactions to that culture as the problem to be “treated,” constitutes social control no matter how benign the actual “treatment” may seem.

Report comment

just curious… do you know of any non-toxic cultures that exist in the world, or that have ever existed?

Either way, what do you think would be the best way of going about trying to create a non-toxic culture?

From my perspective, having a “constant supply of people who need help” isn’t necessarily a bad thing – of course as long as there is also a constant supply of people who willingly give help. Isn’t that what society is all about? Or do you think that a non-toxic society consists solely of independent and competently functioning individuals who don’t need each other in any way at all?

(This is apart from the question of whether psychiatrists can be seen to be helping in any way – just leaving that to one side for the time being.)

Report comment

having a “constant supply of people who need help” isn’t necessarily a bad thing – of course as long as there is also a constant supply of people who willingly give help.

For a fee, of course.

Or do you think that a non-toxic society consists solely of independent and competently functioning individuals who don’t need each other in any way at all?

No, but that’s an apt description of the pretense we currently maintain, aided by “profesionals.” Needing “each other” is quite the opposite of needing psychiatrists.

Report comment

Thanks for this uplifting report Robert. Beautifully written and wow, what beautiful people these are to have set up a truly helpful center and another drug-free ward. Kudos to them, especially Ole Andreas Underland, as well as Tom Liudalen, Mohammed Usaf and the Fellesaksjonen leaders. I must send this report to a few mental health authorities in our country.

It is incomprehensible the public system and traditional psychiatrists are so opposed to referring patients to this Center but it’s no surprise. It speaks to the underlying truth that psychiatry is not about a patient’s best interests, human rights or autonomy. I am so glad they oppose giving patients a diagnosis in order to work within the public system.

These sentences stood out to me:

“We wanted a more holistic, human way of meeting people, where you ask people what their problems are, instead of just diagnosing people.”

“And another thing that causes such problems is the journals, what the staff writes about the patients and then the patients read all of the bad things written about them. We wanted the journals to be made together with the patients.”

So no harmful labels, no forced drugging and no character assassinations for people already downtrodden and traumatized! How totally refreshing and helpful!! Thanks for all your time and effort going to Norway and producing this excellent report.

Report comment

Rosalee,

“INSTEAD of JUST diagnosing people”…….

I believe they don’t lose any diagnosis, in fact it IS what gets them into this place. And in fact, there is a fight to try to get in there, only through the grace of your shrink are you allowed, or through the courts.

Hoping it’s not another business venture, but then I am pretty much disillusioned and not easily sold, as long as the story of MI continues.

I don’t think their health records suddenly wonderfully disappear, perhaps if they are lucky, this house will pronounce them as “recovered”, which means not much if other records remain.

Report comment

Oh, maybe I misinterpreted that…Traditional psychiatry diagnoses without asking or caring about problems or circumstances someone is facing and it seemed this Center wanted to avoid that….

It was this information that made me think they did not “diagnose” :

“He and Liudalen have thought about turning Hurdalsjøen into a public hospital, but doing so would require operating within a stricter set of guidelines than they do now as a private one. For instance, they would have to give patients a diagnosis in order to be in accord with that public system, yet that is NOT something they want to do.”

Report comment

Such a quick and positive response from Norway – one big medication-free treatment center for those who lost something important. The building is like an oncological hospital in south-african republic.

Report comment

Good song about ingesting illegal drugs, i believe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jR_r2ryyzU

Report comment

This should be the future of psychiatry in ALL countries.

Report comment

anomie, you often put into words in an eloquent way, the things I try and mutter about.

I actually somewhat agree that “having a job is the most important factor in a person’s life”

It is because the way society is constructed, we internalize “failure”, if not contributing. It is the way we are reared, by society.

It is true that everyone needs a feeling of worth. BUT I am absolutely convinced that labeling and reinforcing a person’s sense of failure, has been what psychiatry does. Not just within the people that seek ‘help’, but by the whole dam constructed crazy loonybin system.

In fact all the system is comprised of is the view that anyone who has a hissyfit, or cries, or gets depressed, overwhelmed, is MI. They have to get out there, stop crying and pay their taxes.

I read an article about suicide among health professionals. And as usual, it did not mention psychiatry, meds, MI. It mentioned “pressure”, “fear of speaking out”, and how poor doctors live under pressure. Within non professionals they use the term MI.

Their “mental health issues” seem to be a natural progression within oppression, not a disease.

https://www.boardvitals.com/blog/why-doctors-commit-suicide/

True, we all like an ability to work, but how society is constructed means that we have the option of getting a piece of what is on the conveyer belt which is not even close to being fitting to human personality. We created a monster and now those who don’t feel a fit, or come from ancestral oppressions, are left thinking they are somehow not right and THAT is what gives a shrink his cushy job. Riding on the backs of those who fall into trenches dug by society. PLUS making sure to designate them as failures so the shrinks can ensure their continued employment.

Shame on psychiatry. And shame on general area of medicine to participate.

Report comment

What l would give to have this kind of care and treatment, are there any opportunities for people outside Norway to receive this kind of help? I would .be grateful to the editorial team if you could inform me.

Report comment

Thanks for these comments. Rosalee, Re diagnosis: The “patients” may arrive with a diagnosis, because they are arriving from a public mental health system. But they aren’t being viewed through a diagnostic lens.

Also, the user movement thrives in Norway, and We Shall Overcome is one of the oldest psychiatric survivor groups in Europe, and perhaps the oldest of any group still active today. One of their members works there now, and as I wrote, this is the place that when one of their own members had need for a respite/hospital, this is the one she fought to come to.

My point is that the User Voice, which includes the psychiatric survivor voice, is very much present at this place. White Eagle is a small user group that also very much has a psychiatric survivor perspective.

Report comment

The concept of a “user movement” plays fast & loose with what “movements” constitute. It also validates the euphemistic idea of “users” who “consume mental health services” (not enough quotation marks to go around here). A movement usually is meant to “move” towards a definable goal, and usually has a definable adversary. Talking about loose clusters of reformist-minded “survivors” as a “movement” would allow even self-denigrating victims of psychiatry who have the misfortune of finding themselves in NAMI to be called a “survivors’ movement.”

Personally I question whether those who have embraced psychiatry or a psychiatric label can be truly considered “survivors.” Which is why I prefer “inmates” and “outmates.” But I don’t want to get back into those semantics this week.

Report comment

I once asked my GP for a referral to a “good psychiatrist”. Her answer was, “don’t use “good” and “psychiatrist” in the same sentence.

I loved it, yet over time I came to the conclusion that she has that one foot stuck in the system.

It is almost surreal how she is against psychiatry yet participates in it and not just because the system dictates it, for fear of not being ‘that colleague’.

In some ways I found the wishy washy stuff more frustrating.

The people that say “you’re not MI, but that one sure has a screw loose”…..Then I know that I might become “that one”.

Report comment

In realistic terms, OldHead, part of the problem entails treatments that arose out of viewing so-called “mental disorders” as physical conditions requiring physical remedies (shock, drugs). The problem is that the physical remedies invariably involve doing physical harm to the patient/client. Any hospital that doesn’t use drugs, in my opinion, is an improvement for the simple reason that less drug use is going to mean a less physically damaged population. I would think that less or no drug use is, under almost all circumstances, going to mean less iatrogenic disability and, that it is, therefore, something to be desired. As is, everywhere you go, on every hospital ward, it’s always the same drug, drug, drug approach, practice, and mentality. Oh, yeah, everywhere you go besides this private place going up in Norway. Okay. Iatrogenic harm is a separate, but related, issue beside that of physical segregation and imprisonment. Two wrongs certainly don’t make a right, however, a right is definitely to be considered an improvement over any additional wrong. If you were working for many rights, one right is, I imagine, a good place to start.

Report comment

“If you were working for many rights, one right is, I imagine, a good place to start”.

I agree Frank.

Report comment

If this is a response to anything I said Frank needs to be more explicit.

Report comment

Okay. I’m not bitching about any drug free hospital going up then. That’s a very rare phenomenon actually. I’m more concerned about protecting people from some of the harm that comes of psychiatric drug use. I never had an option when it came to drugging in the hospitals (sic) to which I was imprisoned. I think it is a very positive thing that this one private facility is going to be doing something different.

Report comment

Anomie — By “inmates” and “outmates” I mean those who are incarcerated should be considered “inmates” and those who are subject to AOT or “community mental health” should be considered “outmates.” Just as some prisoners refer to what we tend to call “freedom” as “minimum security,” i.e prisons without bars.

Report comment

Sam — Actually many of us would be happier with being called nuts, having a screw loose, etc. than with being called “mentally ill,” which implies scientific legitimacy when it’s basically just people calling each other names.

Report comment

Robert, thanks for the clarification people who arrive are not viewed through the diagnostic lens. That makes a huge difference. As does the fact there are no drugs and people are free to leave whenever they choose.

Report comment

John,

Look up the hospital on the website, and contact them through there. They have had patients from outside Norway, but of course those patients are private pay. https://incita.no/

Report comment

I think Public Medical Systems can shop around for suitable care not available nationally, within the EEC,

I know Ireland uses UK Health facilities.

The thing about Hurdalsjøen is that it practically offers a “cure”.

Report comment

I don’t think Norway is a full member of the EEC, but I think it is closely connected.

Report comment

These guys would do well to learn about supernutrition, which would fit into their program well, as they are interested in their residents’ (“patient” doesn’t work well here) physical and mental well being.

Report comment

Everyone needs a sense of agency, control, freedom and privacy, of being heard, included and valued for who they are, not the objectification, isolation, exclusion and brute force used by traditional psychiatry, which is essentially sanitized brutality.

Report comment

Thank you for this inspiring and very moving report of that the dream of humane psychiatric treatment is indeed possible and how important the peer-support is for success. Very curious to know – Has there been any scientific publications of the results at the Norwegian hospitals yet? Would love try to help develop more of these in Sweden and make scientifically proven psychiatric aid the new normal (CONSENT. Self-influence and no paternalistic care, being able to be out in the nature, exercise and proper nutrition, sleep-school and peer-support).

Report comment