As is the case with all MIA affiliates, Mad in the UK seeks to challenge the existing power structure in psychiatry and prevailing beliefs. That is its mission, and it drives its editorial content.

Various people have joined or left the group since MITUK was launched in 2018. Currently there are five people, a mixture of professionals and current/former service users, who run the site in a collective manner. There is no designated editor, and no one person is “in charge.” Blogs and other content are posted by each of the five members.

“We describe ourselves as a collective,” said one of the founding team members, who preferred to remain anonymous, on a recent Zoom call.

The desire of several in the group to remain anonymous is unusual among MIA affiliates. In most cases, the editors announce themselves in an “About Us” section on the site. The reason for the anonymity in this case, said one of the editors, is “we get a big backlash . . . it does feel like being on the front lines, being shot at.”

The backlash that they are experiencing may be, ironically, because the public debate in the UK is more robust than in the U.S. and most other countries. As a result, the powers-that-be in the British mental health system may feel more threatened than the powers-that-be in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The UK has long had a critical psychiatry group, and there are a number of prominent UK professionals that have written for MIA—Joanna Moncrieff, John Read, Sami Timimi, and others—who are well known in the UK and beyond. Plus, there has long been a robust psychiatric survivor movement in the UK.

The critics in the UK have presented an alternative to the DSM (“the Power Threat Meaning Framework”), presented evidence-based arguments that tell of harm done from ECT, the relative inefficacy of psychiatric drugs, even over the short term, and industry’s corruption of psychiatric drug research. And they have had an impact—cracks have appeared in the UK’s publicly run National Health Service. This may be easier to achieve in a system in which, most of the time, a DSM code isn’t required, and alternate approaches to care are available in some locations. The NHS practice of psychological formulation even emphasizes the stories behind people’s emotional suffering.

Yet, say the editors of MITUK, the dominant narrative is still overwhelmingly disease-based, and that narrative still dominates both the mainstream media and everyday conversations. Not enough people are aware of the harm that can come from psychiatric care, nor are they aware of the science that shows that. Nor are most aware of the efficacy of non-medical approaches.

In short, said collective member Charlotte Beale: “The medical model has a grip.”

A writer with lived experience, Beale has told her own story on Mad in the UK. As she writes in her opening: “Eight years after beginning ‘treatment’ for an ‘eating disorder’, I was eating worse than ever. Yet three years after quitting that ‘treatment,’ food is a pleasure, not a problem. This is curious, isn’t it?”

In her case, her experiences involved a private clinic, not NHS. But as she explained in the Zoom call, “It was still quite diagnostic.”

With British society as a whole still immersed in the medical paradigm, escaping from it is hard, Beale said. Discovering Mad in the UK’s team of volunteers, all committed to challenging that paradigm, felt revelatory. “I don’t know any other forum like it in the UK. . . . It really was like a breath of fresh air.”

Mad in the UK describes its mission as “Fundamentally re-thinking UK mental health practice and promoting positive change.” Content includes blog posts, artwork, and podcasts; stories from around the web highlighting the latest research and commentary; links to Mad global affiliates; and online events and courses. Currently, the homepage showcases a short film based on a poem by collective member Jo Watson and links to the “Disorder 4 Everyone” online festival (associated with the Drop the Disorder Facebook page).

While Mad in the UK is open to varied perspectives, commenting guidelines stress civility and caution against personal attacks, bullying, and shaming. The stories and blogs are vetted, with Mad in the UK setting a standard for what it will publish: If a blog assumes the validity of the medical model paradigm, the editors don’t see it as suitable for publication on the site. “We are very, very strict about that,” said Beale’s colleague.

The collective has also set a standard for language. They avoid using terms that are the language of the medical model, such as “treatment” and medication. “Recovery” is also problematic, implying that someone harmed by the system should now get to work and heal themselves. “Mental health,” used as a reductionist term for human feelings and emotions, is sometimes unavoidable but does tend to imply an analogy with physical health.

Such standards are meant to change not just the topics being addressed but the ways they’re discussed—given the medical paradigm’s current sway in controlling conversation. Those engaging in such dialogue on Mad in the UK are part of a large, loose, overlapping group of people with a shared critical perspective who participate across multiple efforts and platforms—including, for some of them, Mad in America. Creating an affiliate for the United Kingdom had long been in the back of their minds when, four or five years ago, the idea was proposed by Watson to MIA founder Robert Whitaker.

The website launched on September 6, 2018, run by a collective of 10 on a volunteer basis. Its five current members juggle duties as best they can; editing is done by “whoever’s least busy.” Another member or two, perhaps, might be added moving forward. Also, perhaps, some crowdfunding: They did have a page a while back, and may try again in the future.

At some point, said Beale and her colleague, they would like to devote more time to actively developing the site and eliciting content. Right now, writers tend to reach out on their own, often crossing over from the Drop the Disorder page or other platforms on the web. Quite a few request anonymity; many lack confidence in their writing.

Beale understands their hesitancy, but she knows firsthand the boost they feel once their work is posted. Recalling her first piece for Mad in the UK and the reader comments it generated, she said, “It was brilliant to get published.” In the collective’s view, giving others that same opportunity—lifting them, affirming them, telling their stories and giving them a voice—is vital.

Also vital, said Beale’s compatriot: Showing people what works and what doesn’t. “We are highlighting the catastrophic damage” of so-called “treatments.” They’re highlighting research, and outcomes, and promising alternatives.

There are positive signs of change, they say. Trauma-informed care is gaining a foothold in the UK, as is Open Dialogue. In addition, the Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) has inched its way into the system, lowering bed use and lessening coercive treatment at 14 inpatient wards in London. It is developments like this, that give the MITUK members hope.

Being part of the global Mad community also gives them hope. Sharing their sense of mission with allies and supporters around the world: “It feels, you know, fab,” said the member. And it’s inspiring. “It keeps you going, and I hope we can offer some inspiration, as well. . . . We really, really want to be part of a supportive alliance. That’s the only way things can happen.”

Already, impact is evident in multiple directions. For a start, readership is swelling. “Tens of thousands are coming to Mad in the UK,” Beale said, with numbers also exploding on social media.

But beyond that, another mark of impact—a considerable one—is the blowback itself. The same hateful attacks that prompted Beale’s colleagues to go nameless also, ironically, gives them hope. It’s a sign that “the diagnostic paradigm is crumbling at the foundations,” said the member in question. And when an old order collapses, those who defend it inevitably turn vicious. “There’s always resistance, isn’t there?”

How long that collapse will take, no one knows. Years. Decades, maybe. But one way or the other, “It’s gonna happen. It is happening. It is happening.”

*****

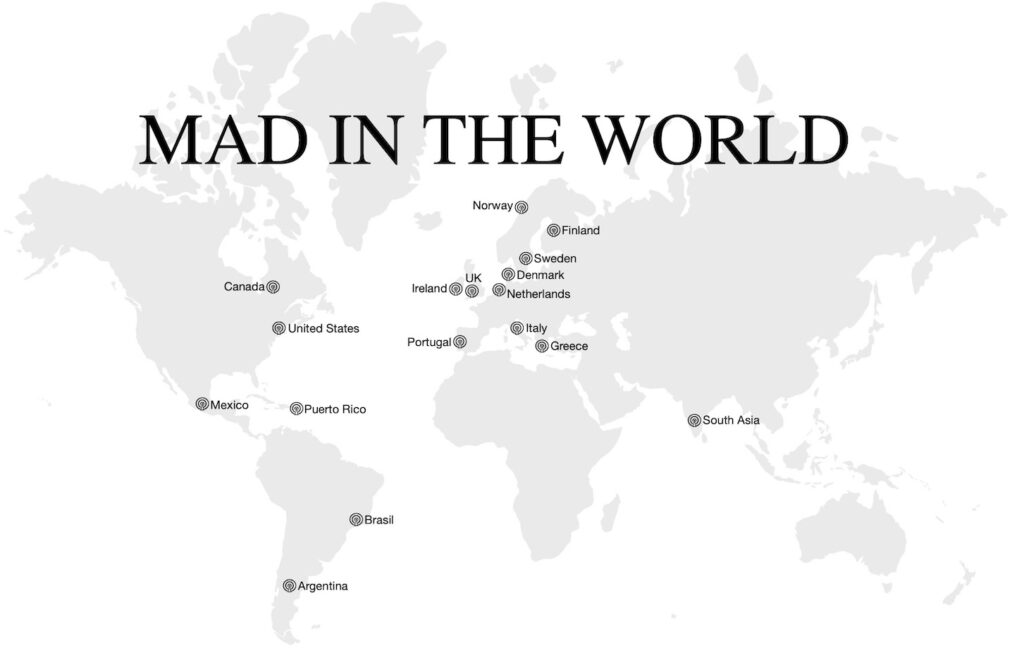

MIA Editors: Over the next 10 weeks, we will be publishing a profile of each of the Mad in America affiliates. They have banded together as a “Mad in the World” network.

“It’s a sign that ‘the diagnostic paradigm is crumbling at the foundations,’ said the member in question. And when an old order collapses, those who defend it inevitably turn vicious.”

Indeed they do.

I must say I do appreciate the truth speaking British psychologists and psychiatrists – they’ve done, and are doing, way more truth telling than almost any psychiatrist in the US, except Peter Breggin.

Report comment

impact is evident in multiple directions. For a start, readership is swelling. “Tens of thousands are coming to Mad in the UK,” Beale said, with numbers also exploding on social media.

Report comment

Thanks to All who contribute. I have been in the system since 1994. It was all too easy to get a label and be tossed in the rubbish. They did not know me, my capabilities, my intelligence, my perseverance, my determination and my skills and experience.

If psychiatrists have so much power then it really is about time that we pulled the plug. I know an excellent electrician. He really is all heart.

Report comment