Epiphany, revelation, a-ha’s. The people who run Mad in Finland have experienced profound awakenings in the course of their lives, moments of awareness when they understood the failures of the psychiatric disease model and saw its harms—in their own lives, and in others’.

They’re now working to bring that same awareness—those same a-ha’s—through their efforts with the Mad in America affiliate. They’re spreading the word, illuminating the facts on withdrawal and non-medical conceptions of depression and psychosis. They’re reaching new eyes and drawing new voices into the conversation.

“There are more and more people who see our pages,” said editor Heidi Tommila, “and start to think about their own experiences, also.”

Tommila was on a Zoom call with her colleague Soili Takkala, who founded the country’s first SSRI peer-support withdrawal group and co-founded the NGO that spawned Mad in Finland. The way they see it, getting the word out is half the battle: Once someone has that critical awakening, there’s no quashing it.

“It’s like letting the genie out of the bottle. You can’t put it back, once it’s out. . . because it resonates with people’s actual experience,” Takkala said. “It changes things.”

The Finnish mental health system is famous, in critical-psychiatry circles, for its innovation and implementation of the non-medicalized Open Dialogue model of care. First developed in Western Lapland, the model “is almost nowhere in Finland,” Takkala said. In general, the biomedical paradigm still prevails—and too often, she added, someone might suffer some human struggle and wind up placed on psych drugs.

In her case, she was 20 when she first experienced depression. Three years later, in 1988, her father died by suicide. Sometime after that, she started therapy, then SSRI’s. Over the years she tried to go off them—again, and again, and again—but each time, her withdrawal symptoms were misdiagnosed as relapse. Doctors fed her the “brain chemistry” line. They told her she’d need the drugs for life. Finally, in 2011, she managed to quit them for good.

In recounting her story, she recalled a piece of wisdom a Buddhist meditation teacher gave her. Regarding the psych drugs, the teacher said: “Eventually you’ll get rid of those. And when you get rid of those, then you can help other people with those experiences.”

That, she said, was the key. Helping people.

Just how became clear when, in 2014, psychologist Aku Kopakkala appeared in “Depressing Drugs (Masentavat lääkkeet),” an episode of the Finnish investigative-journalism series MOT. In it, he bluntly criticized the biomedical approach; the next day, he was sacked from his job with a private health care provider. Journalists “had a field day,” Takkala recalled. About a month later, Kopakkala gave a public lecture on the topic—“and I was listening to him, and it felt like a revelation. I finally saw the connection between my own long-lasting withdrawal struggle and this whole sort of ideology.”

From that revelatory moment, the basis for the MIA affiliate was formed. As a writer with years of experience in publishing, she reached out—initially with a book in mind—and ultimately formed the SSRI-withdrawal group. Every other week, they organized lectures and similar events, bringing in Kopakkala and others to speak, in public, about withdrawal and related issues. And an NGO was created: Need Based Treatment (Tarpeenmukainen hoito, or TaHo).

That was November of 2016. A year or two later, TaHo’s web page morphed into MadinFinland.org.

The site is now jam-packed with content: articles on research; personal stories, commentary, diary entries and other blog posts; reflections on “Mieletön psykiatria” (a play on words translated as “insane” or “mindless” psychiatry) by Tommila and an anonymous author with lived experience; stories and information on SSRI detoxification; translations of Mad in America articles and links to MIA global affiliates; a data bank offering info on side effects, instructions for tapering, and other topics; Tommila’s correspondence with a history researcher and philosopher; and links to various sites and resources.

Operating on a voluntary basis, Mad in Finland isn’t run by professionals, Tommila said. Its contributors aren’t trained in journalism. “We’re more like thinkers”—mostly people with stories and insights, doing their best to share them.

Her own epiphany came several years ago, as a young mother on maternity leave. She had just moved to a new location with no friends nearby, and “I was quite alone, quite alone.” In that isolated state she experienced psychosis for four or five days, enduring it at home. A month and a half later, with a resurgence of anxiety, she entered the hospital—already understanding “that it was not what I needed. But I didn’t know where I could go.”

What she knew: “I just need peace, and I need rest, and I need someone to talk with me about my new ideas, my new thoughts that my head was full of. And everything was just taken as symptoms when I was in hospital.”

After five days, she went back home; two months later, she stopped antipsychotics on her own. She had difficulty sleeping. Difficulty with other aspects of living. But she went back to her old job—never planning to stay for long, but proving to herself and her family “that there is naturally nothing wrong with me.” After a year, she quit. That’s when she resolved to work toward positive change. And that’s when, four years ago, she became involved with Mad in Finland.

Being proactive, putting herself out there—none of that is easy, Tommila said. But bearing witness feels necessary. So does the sense of “cooperating and supporting each other” in a community, gradually building, that’s committed to challenging the paradigm.

“There’s many people in mental health who want to do something differently,” said Kopakkala, also on the Zoom call, “but they don’t know how.” In his own case, his life was altered when he spoke the truth eight years ago. But there are more voices in the wilderness these days, he said. Compared with a decade or so ago, many more people are aware of the controversies surrounding mental health and the problems with drugs.

“But practices are not people,” he added. And those need to change, too.

So far, the affiliate has seen some evidence that they are, in fact, reaching more populations and prompting more a-ha’s. Most notably: In 2019, the official Finnish guidelines on depression treatments were updated, citing the dangers of prolonged withdrawal syndrome and advising slower tapering. The change was “just an inch,” Takkala said. “But, you know, a critical inch.” Getting the message through was a triumph—“not the final triumph,” but a significant strike in the right direction.

What gives them hope? For a start: Other MIA affiliates around the world. While each country has its own particular focuses and areas of concern, Takkala said, “It’s wonderful to be part of a global community—and it gives the backup and the background support we need.” It also demonstrates that their efforts and experiences aren’t limited to a handful of survivors.

Another cause for hope: The gradually shifting conversation across media. More and more, challenges to the pharma-driven disease narrative are being published in mainstream outlets; more and more, psychiatric survivors are being heard; and more and more, professionals are opening themselves to alternate views. Moving ahead, Tommila would like to bring them into the dialogue as contributors at Mad in Finland.

But already, in Kopakkala’s own practice, he and his colleagues shun words like “diagnosis.” He explained: “We want to know who they are, how they’re living, what their problems are, how they see themselves. We don’t diagnose.”

Raising his hands to his eyes like spectacles, he added, “We don’t want to see them through glasses. We want them to tell their own story in their own words. . . . And I think we shouldn’t be allowed to put diagnosis on other people—it’s violent, somehow. It’s abuse of power, to diagnose other people. It’s not fair. It’s not fair.” As it stands, instructing those in distress to accept such labels “is self-stigmatizing—and that’s the most terrible thing in this whole power play.”

But at least some shifts in attitude are happening, Takkala said. “At least there’s sort of a wider perspective to different ideas—and at least there are ongoing, public dialogues on psychiatric drug withdrawal via her work with TaHo. The next one, on April 7, will feature prominent neuroscientist and researcher Mark Horowitz.

“And that’s great progress,” Tommila said.

True progress will come when such conversations aren’t even necessary. The best possible outcome, as she sees it: to “not need” Mad in Finland any longer. To not need so many voices raised in protest. To not need a platform pushing against the system, because the system is wholly reformed.

“The change,” she said, “is more important.”

*****

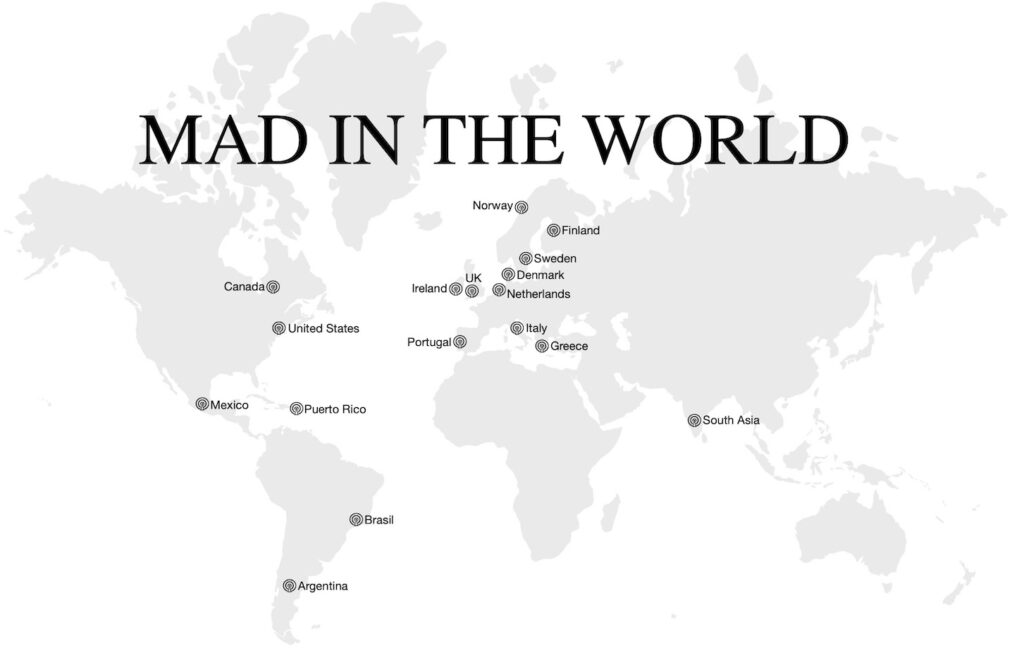

MIA Editors: Over the next 10 weeks, we will be publishing a profile of each of the Mad in America affiliates. They have banded together as a “Mad in the World” network.

“….In recounting her story, she recalled a piece of wisdom a Buddhist meditation teacher gave her. Regarding the psych drugs, the teacher said: “Eventually you’ll get rid of those. And when you get rid of those, then you can help other people with those experiences.”…”

I remember a buddhist monk being asked a question regarding the taking of antidepressants – He Didn’t Say “I’m not a doctor” – He said “Try to come of the drugs very slowly and very carefully” .

Buddhist Meditation is a brilliant cure for “low mood”.

Report comment