Note of appreciation: I am indebted to Dr. Brooks’ three daughters, without whom I could never have written this tribute. They corrected many items and supported me in every way possible. One request they’ve made is that, except for the introductory paragraphs, they want me to refer to Dr. Brooks throughout as Dean. He often told people, “Call me Dean.” A major goal for me in writing this was to emphasize his goal of humanizing the state hospital and he certainly endeared himself to me as Dean in the hours I spent with him before his passing. Thank you Dennie, Ulista and India.

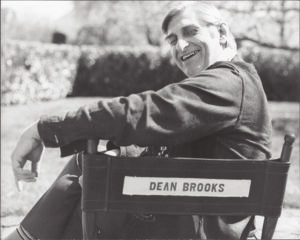

Let’s say you were a person in the community and wanted to get the superintendent of your state hospital to read a message you sent through the mail. If that superintendent was Dr. Dean K. Brooks, you would soon realize you might wait awhile for a response. His instructions were that the top of the mail pile was to be that from patients. Next was mail from their families. That was to be followed by staff doing direct care, then staff who were supervising direct care staff, then those supervising the supervisors. After all those, attention was to be paid to the people he reported to—the Governor and then finally the public. And later, when the state mental health commissioner came along, that would have been me. You would think that was not business as usual and maybe even a radical change—putting patients first in the priority system.

This is a report that will tell you stories that indeed challenged the mental health system—stories of a state hospital leader who did just that—placing patients as the most important people. Dr. Dean Brooks likely would have been the first to acknowledge that he was not perfect by any means. And he would not suggest that he had reformed the hospital and certainly not the mental health systems. But given the context of his time he was a radical.

He began working at Oregon State Hospital in 1947 and served as that institution’s superintendent for 26 years. The years before this were not noted for humanizing the patients who were confined there. In fact, the conditions of state mental hospitals had just been described in 1948 by journalist and social activist Albert Deutsch in a searing exposé, Shame of the States. Dr. Dean Brooks inherited the kind of deplorable conditions documented by Deutsch. Just one example—prefabricated metal Quonset huts were used for housing several hundred geriatric patients.

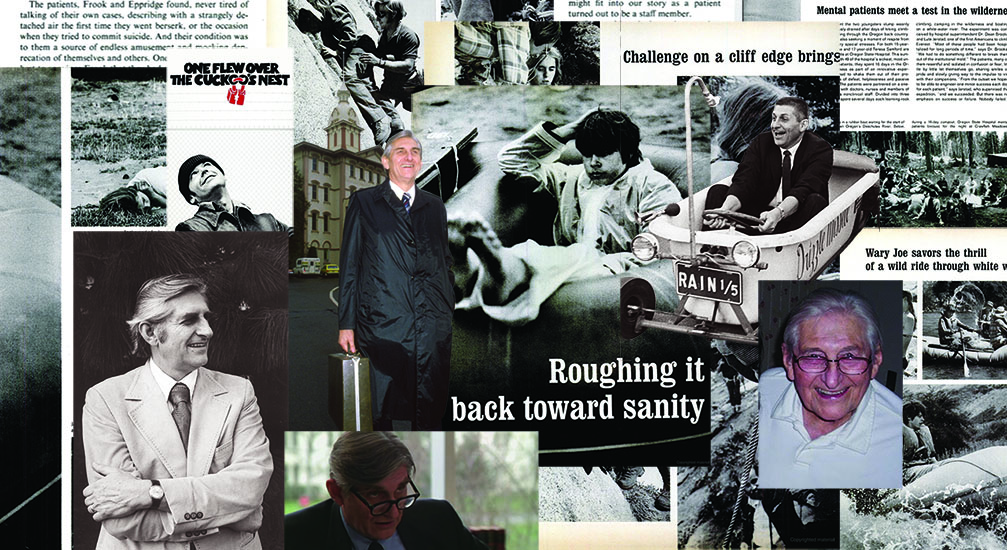

Dr. Dean Brooks is best known for his decision to allow the film One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest to be filmed at his state hospital and even appearing in it as Dr. Spivey, the admitting and treating psychiatrist for Randle P. McMurphy. But he deserves to be known as the superintendent who approached everything he did with the unusual idea that patients were people first and foremost, deserving every respect as human beings. While this may sound like what state hospitals and facilities of all kinds say even today that they are doing, this report will tell his story—not only what he said but, most importantly, what he did. The reader can decide whether this tribute to Dr. Brooks embodies the standard that should become expected of all mental health services.

First though, how did Bob Whitaker and I connect with Dr. Brooks, or with Dean as we got to know him? And just as important, how did Dr. Brooks connect with us?

The story is this: Bob’s book Anatomy of an Epidemic was published in early 2010. I ran across the book right after it came on the market and it hit me in the side of the head. I had already worked for 40 years as everything from a psychiatric aide, an alcohol and drug counselor, a case coordinator and into program development at county and state levels. I had also been Oregon’s state mental health and addictions director. I was primed for a different way of looking at mental health services and Anatomy gave me the direction I needed.

I emailed Bob, thanking him for writing it and never expected to hear anything back. But in about two days I did. From that we brought Bob to Oregon three or four times. On one of those visits I introduced him to Dean. I had gotten to know Dean by then because his family wanted someone to spend time with him and write down as many stories as possible, given that he was in his early 90s by then. Those stories had a powerful theme—for Dean it was all about the people who had ended up as patients in his state hospital.

What I didn’t know was that Dean had already read Anatomy of an Epidemic and had purchased a dozen copies. He was also obviously taken by the book and, in fact, had been distributing it, including to the state hospital superintendent and a number of psychiatrists and physicians there, one of whom was his daughter, Ulista, an internist. So there was a strong connection between the three of us that continued up until Dean’s passing in 2013 at the age of 96.

He graduated from medical school at Kansas University in 1942 and chose Akron, Ohio, for his internship, where he worked with a surgeon, Dr. Bob Smith, who had everyone’s great respect for his knowledge and skill. Dr. Smith was known for the precision in his operations, such that post-surgery stitches were hardly noticed. But this surgeon also had a penchant for admitting alcoholic men to the hospital. So, young Dean asked why Dr. Smith was letting all these men into the hospital instead of sending them to jail where they belonged.

Someone asked him if he knew who this Dr. Bob Smith was. “Didn’t you know? He is one of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous.” He soon got to meet the other co-founder of AA, Bill Wilson. He was changed greatly by his encounters with these two men and eventually there were AA meetings in Oregon State Hospital. But that is getting ahead of the story.

By 1943, World War II was in full swing and the United States’ armed forces needed even more men, especially physicians, so all physicians in medical school were told they were drafted. They could choose which branch of the service they wanted or just be assigned the Army. He told me he decided to join the Navy because “I wanted to sleep in clean sheets.”

Although his goal was to be a pediatrician, he was immediately assigned to Honolulu, which he didn’t think was all that bad. But within 24 hours he was headed for a Landing Ship Tank boat, which he soon learned were known by seamen as “Long Slow Targets.” Soon he was in the middle of seven deadly South Pacific battles. Marine and Navy corpsmen suffered horrendous casualties of over 67,000 wounded and over 23,000 killed or missing in the South Pacific.

He was the deck triage officer whose job was to decide who would be treated on the basis of survivability. While he would later refer modestly to these battles as “skirmishes,” they were not. They were horrendous and life-changing experiences. They indelibly imprinted on him the role of trauma and suffering in the lives of the patients he was to be responsible for in his state hospital tenure.

His military experiences continued when the war ended and he was sent to Camp White near Medford in Southern Oregon, the site of the Navy Hospital. It was there that he met the medical director, Dr. Frosty Miller, who was recognized for his sensitivity to the plight of returning troops. Dr. Miller told him he should go into psychiatry because “I like your personality.” Dr. Miller’s words had real impact because he was the Veterans Administration’s Chief of Psychiatry for the West Coast.

After Medford, Dean went to the VA Hospital at American Lake Washington.

Beginnings at Oregon State Hospital

Soon, Dr. Miller left his VA position to take a psychiatrist position at Oregon State Hospital and before long he invited Dean to join the staff at Oregon State Hospital. In 1947 Dean moved to Salem to take up his new position there. During his first years at Oregon State Hospital, he learned a great deal about psychiatry from Dr. Miller, who had trained in psychiatry at the University of Colorado. Some of those lessons took place as they walked down hospital corridors.

With only two years of experience as a practicing psychiatrist and no formal training for it, Dean was appointed Assistant Superintendent in 1949. In the decades after this first promotion, he never took a course in psychiatry, which many of us would consider a good thing.

At times he wondered whether he should take courses and become a board-certified psychiatrist, but at some point, he spoke with an official in Rochester, New York, and asked, “Would it make a difference?” The official pointed out one respected psychiatrist after another who was not certified. At the time, Dean was already one of them, as the President of the National Superintendents Association and the leader of a commission for the National Institute of Mental Health. The conversation ended with the certification expert telling Dean, “You may as well go out and buy yourself a case of booze.”

Treating Patients as People

Where did all this lead? Dean stated over and over, “I loved the patients.” To make this real in an institution like Oregon State Hospital, he insisted on a constant review of operations there. He told me this was a process requiring “eternal vigilance,” the price of liberty, referring to a quote attributed to the abolitionist Wendell Phillips in 1852. This turned into a career-long practice of making rounds on every ward, every shift, every month. He often even took his daughters with him.

Soon after being named superintendent in 1955 Dean started the Superintendent’s Council. He invited patients from each ward in the hospital to elect two representatives to the Council. There were two rules: no smoking and no personal gripes unless shared by other patients. The only staff were Dean and his secretary, who kept notes. No topics were off limits. The Council had the right to call anyone to a meeting if they could help. Typically, 20 patients would participate and the meetings were held in the Superintendent’s conference room.

One subject that came up quickly was the lack of personal financial accounts. The patients said that except for a few dollars, their monies were held in the State’s General Fund. They wanted answers to this unfair practice. Dean got on speakerphone immediately with then-State Treasurer (and later, Governor) Robert Straub. Straub agreed this did not seem fair and said he would look into it personally. Straub came to the next week’s meeting to announce that the policy had been changed and monies had been placed in the personal accounts.

Before long the patients brought up the fact that extremely hot coffee was being served on one ward in the mornings in wax paper cups. Dean was incensed. He had one of these cups filled with extremely hot water, gripped it by the edges and headed straight for the food service manager of the unit and handed it to her. She yelled in pain and said there was very hot water in there. He had made his point.

He heard from members of the Superintendent’s Council that there was a unit that had feces smeared all over the walls. He went straight over to the ward to check it out. Staff told him that they were rationing the toilet paper to patients because they were using too much and clogging the toilets. Dean told them that there was obviously a patient who needed more toilet paper otherwise the walls wouldn’t have such a mess on them. The Director of Nursing was nearly fired over this.

The members of the Superintendent’s Council were committed to improving physical conditions at the state hospital. They held raffle sales to raise money for several projects, one of which was to repair a statue and fountain, known as “Baby Hercules” that had long graced the grounds of Oregon State Hospital but had fallen into disrepair. The Council wanted to get it repaired as a gift to the community. Funds were raised to bring “Baby Hercules” back to life, the product of this early form of patient advocacy—all supported by Dean.

Soon after getting it repaired, it was vandalized. The Council chose to repair it a second time, and unfortunately it was vandalized a second time. The statue was then returned to the warehouse where it stayed until a new facility was built in 2010 and is now finally in its original place at the entrance of the restored Kirkbride building, one of the original structures at Oregon State Hospital. The Council was praised for its work and Dean apologized on behalf of the community they had wished to share it with.

Another situation that came up was that of Carl, a 94-year-old man who had worked in the barns when there were teams of horses at the hospital. The state hospital at that time owned what was called the Cottage Farm. Patients worked there with live cattle, pigs, chickens, and a retired team of horses. There were also large fruit orchards. Carl had cared for horses and the barn under this arrangement until all hospital activities were consolidated into one location.

One day, Dean noticed that Carl always wore very large boots on his opposite feet because that was the only way they would fit. The staff told him that they had only one size of boots, allowing the crew (like Carl) to step in and out of them in a hurry so that they wouldn’t have to hold up the crew boss as he went to lunch. It turned out that when the warehouse was called, they had all sizes, and had for at least the previous sixteen years.

The next day, then-Governor Straub happened to be visiting the hospital and walked with Dean out to where Carl was working. He had new boots that fit and he thanked Dean for getting them. When the Governor and Dean asked a staff person how this happened, he replied that “We got them because somebody high up just raised hell.” But Dean had not done it this way. All he had done was to ask some questions using his principle for change, “Find facts, not fault.”

A Bushel of Shoes

Dean became known to many within the field of psychiatry by writing an article, “A Bushel of Shoes,” which was published in a key American Psychiatric Association journal, Hospital and Community Psychiatry, in 1969. He wrote it after a trip to Hudson River State Hospital just after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. In this somber mood, he made rounds with the hospital superintendent, Dr. Snow.

The hospital had at one time been a shining example of mental health care but, as they were leaving at 1:30 a.m., he and Dr. Snow stopped in at a 2-story building which housed about 60 women. All the lights were on and every one of the patients had a pillow over her head in order to try to sleep. When Dr. Snow asked the staff, “When do you turn out the lights?” they answered that they didn’t shut them off, adding, “It’s the law.” The lights had been burning for the previous 25 to 50 years. They went out immediately.

When Dr. Snow asked a little later on this visit why there was a bushel of shoes on the units, he learned that staff collected patients’ shoes each evening, put them in a basket, and when morning came, the patients were told to pick out whichever shoes they could find first.

In “A Bushel of Shoes,” Dean described the incidents he had experienced at Hudson River State Hospital and defined the dehumanization he had observed there “as the divestment of human capacities and functions and the process of becoming or the state of being less than a man… We who work there [in state hospitals] like to think that everything that takes place is a part of treatment, suggesting that the hospital takes over the mentally ill person to make something better of him… But sometimes we make the person into a career mental patient. We do many things to help create such a state—sometimes because we don’t know any better, sometimes because we just don’t care.”

A member of the Council asked him why there was no place to hang towels in any bathroom in the hospital. He admitted that in spite of having been at the state hospital for 22 years, he had not been aware of the fact that there was not a rack or hook in these rooms. He began to realize the pattern of dehumanization that was going on in his own hospital and that it needed far more than a “Band Aid” approach.

He soon started what he called a “massive fact-finding operation.” It involved setting up study groups that brought together staff, patients, community members, high-level state administrators from the Secretary of State’s office, and even legislators. He directed the study groups to look at things from the standpoint of the patients, not “the purchasing agent.” Dean charged the groups with a goal of “prevention of the dehumanization of people in our hospital.” This was a radical departure from what Oregon State Hospital and other state hospitals were doing. The mantra for all these groups was to “Find fact, not fault!”

The groups reviewed hospital practices like clothing, dental hygiene, bathing, toileting, grooming, sleeping, recreation, eating, housekeeping, patients’ money, personal possessions, maintenance, aesthetics, living space, and admission and discharge routines. Each study group came up with findings and then made recommendations for change based on what they had learned.

The housekeeping task force, for example, reported one of the most damning of the findings—the medical-surgical unit was “exceptionally dirty.” The stench in the male medical unit was “inexcusable and intolerable.” Some toilet areas were used for storing cleaning supplies so that an entire stall was taken out of service. Similarly, the food work group showed that some wards served hot food in sanitary ways while others served food cold, sometimes transported uncovered and left that way for up to 40 minutes. The staff serving food were not always washing hands before work, had nail care that was unsanitary, were working in dirty clothes and not keeping hands away from their noses, mouths, and hair.

Another work group pointed to the fact that showers were group facilities with no individual controls. They recommended that all showers be remodeled to provide privacy. So many other deficiencies were uncovered that their report stated bluntly that the state should “tear all the buildings down and replace them with adequate structures.”

The sleeping task force spoke to the difficulties for patients who were given wool blankets which would shrink to the point that the patient could not keep warm. Mattresses were sometimes uncovered, unsanitary, and in need of soft plastics. Some mattresses were in such dire condition that they needed equipment to sterilize them.

One of the groups began looking at practices related to admissions. In order to gather more information, student nurses were “admitted” to the hospital and required to go through all the routines required of patients. A finding that came out of this group was that there were no tampons available to the women patients.

A consistent finding coming from many of the groups was that there was considerable variability in unit practices because they were decentralized and in need of consistent hospital-wide standards, responsibility, and oversight. As a result, standards for the quality of care were carefully written and distributed at regular intervals to assure that changes were made and revised if needed. Recognizing that changes could tend to lessen over time, many of the groups recommended standing advisory committees to continue to monitor conditions. Listening to the voices of patients was the critical ingredient in all this. Again, the goal here was to find fact and not to simply look for people to blame.

The common message coming from these and other reforms was that “It takes people to help people get well.” Dean also frequently reminded staff that “you are either in service to the patient or you are in service to those who are [in service to the patient],” which means that everything is focused on patient care alone.

The Medication Stories

It was during Dean’s service as a state hospital physician and superintendent that psychiatric medications were first introduced. When I asked him about it, he said that he was very grateful to have these new treatments available. When Thorazine came along it was very welcome. He recognized that many of the existing interventions being used were harmful.

But he harbored doubts that medications would be the entire answer to treating patients. He told me the story of a patient, viewed as a hopeless case but who was prescribed these psychotropic medications for about six months. He began to improve and his ward psychiatrist pronounced him ready to begin planning for him to leave the hospital—a day that was never expected to come. But Dean pulled the patient aside for a private chat in the hallway and asked him about the miracle brought about by the medication.

Because the patient trusted him, he admitted that he had been “cheeking them” and then secretly spitting out the pills the entire six months. Dean asked, “Who the hell are the drugs for? The patients or the staff?” He recognized that if medications brought increased hope for the staff, it reflected back onto the patient’s own expectations for recovery.

To further test the effectiveness of the drugs, he tried an experiment that would never be permitted now by the required Institutional Review Boards for research. He took one ward and put all the patients on a placebo for a month without telling them or their prescribing psychiatrist what was going on. At the end of the month, he called the physicians together and asked them to tell him which of the wards it was. Not one could guess correctly.

These kinds of experiences added to his doubts that the new medications really worked as they were advertised to. He came to believe that they should not be used forever, that they might have a similar effect to “resetting a clock” by shaking it. Could the medications serve in the same way—that “once you get it going again, you don’t need to keep shaking it?”

Attracting World-Famous Resources

Many well-known psychiatrists, writers, and philosophers visited Oregon State Hospital during Dean’s years of leadership. A prime example was that of Dr. Maxwell Jones, who was invited to come to Salem to share his ideas about “therapeutic community.” Dr. Jones, a world-famous British psychiatrist, had been treating soldiers in World War II for combat fatigue and found that an effective mode of treatment was to provide soldiers with a specialized group setting instead of the customary individual psychotherapeutic sessions. This led him to the concept of “therapeutic community.”

Before long, Dr. Jones became a staff member at Oregon State Hospital in order to set up a therapeutic community. This was considered a personnel coup and was greeted with amazement when the press learned that this well-known psychiatrist was working in their own state hospital. When asked by several prominent state officials how this came about, Dean simply answered, “I asked him.”

As was a common practice for physicians, Dr. Jones lived on the state hospital campus and, in fact, his house was next door to the Brooks’ residence. The two families often ate at each other’s homes and one night Dr. Jones, as was his practice, was dropping names of famous people he knew. He said that Aldous Huxley (the author of Brave New World) was his friend. Mrs. Brooks challenged Dr. Jones to invite him to Oregon if he knew him so well. He did and before long Mr. Huxley and his wife, Laura, were in Salem and stayed for three days. Dean arranged for Huxley to give a speech to patients and another one to the community. As if this wasn’t enough, Laura Huxley, a well-known hypnotherapist, also led groups talking about her technique using this intervention.

Rudy Freudenberg, the director of the British mental health system, also came to lecture psychiatric residents at Oregon State Hospital, along with Dr. Karl H. Pribram, a world-famous expert on sleep and cognition. The first executive director of the World Health Organization, Dr. Brock Chisholm, stopped in with Dr. David Clark, who was a friend of Dean’s and was the superintendent of a large mental hospital outside Cambridge in the United Kingdom. Dr. Clark too was a courageous pioneer in using the “social model” in psychiatry—unlocked doors, work opportunities for all patients, within the context of a therapeutic community.

Long before most mental health professionals began talking about recovery, Gertrude Behanna, author of The Late Liz, was invited to the hospital to give public talks on the Recovery Model. On one of his many trips to Washington DC, Dean attended a small lecture with Linus Pauling at St Elizabeth’s Hospital. Perhaps most unexpectedly for a state hospital was that Thomas Szasz stopped in. Oregon State Hospital is likely the only state hospital that ever invited him for a visit. While it was not possible to have Bill Wilson and Dr. Bob Smith visit Oregon State Hospital, Dean worked tirelessly to provide resources to AA over the years.

Because of Dean’s prominent profile in several of these advanced treatment modalities, he was asked to become the first director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) as well as take on the Superintendent’s position at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. He did agree to head the NIMH’s Committee on Hospital Improvement Programs (HIP), but he declined both the NIMH director and St Elizabeth’s Hospital position, stating simply that he was serving the patients at Oregon State Hospital.

Stories

Dean was an incredible storyteller. There were stories about him too. They revolved in one way or another around the theme of meeting the patients on their own human terms, whatever those terms were. He frequently quoted the maxim “It’s ALL about the patients,” as will be clear in the stories that follow. He had a simple answer to what had guided him all those years. “I kinda liked it. I took steps if I thought they were right.”

The first one is “the window story.” An idea occurred to him one day to replace the small windows in the Kirkbride building with a large plate glass window. Staff tried to convince him that the patients would break it. But his position was that “The patients will not destroy something they like.” To make the point even clearer, he went further and had large windows installed in several other places as well. Governor Hatfield was so taken by the decision that he told the Saturday Evening Post about it.

Dean was too modest to tell the next story, which was that he remembered every patient’s name as he made rounds formally and informally. A guiding principle for him through his many years working with patients was “to be a little kinder each day.” When asked about which of the patients he found most interesting, he stated simply, “All of them.”

He found that patients were almost all more sensitive to other people’s needs than they were given credit for. Once, during a meeting with staff, a patient sensed that Dean was getting bored and left the room in order to come back with a glass of ice water for him. Another patient who was deaf and blind could only be reached by one person in the hospital—another patient diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Volunteer efforts started after a group of women from Salem’s Jason Lee Methodist Church visited the state hospital. They said they would like to do something to be of service and Dean had them “adopt” Ward 17. The women on the unit were often considered by staff to be “desperate,” psychotic and messy, some incontinent, most disheveled in looks.

Staff had been trying various things to help but with no success. But the church women started by learning every woman’s birthday and then wrote a letter or card to each, and rather than sending them through the internal hospital mail system, sent them through the US Post Office instead. This was the first time in many years most of the women had received mail from the outside world. A birthday party was held each month and the women were encouraged to have their hair and nails fixed up.

Additional volunteers from local beauty salons were recruited so that the women began to get haircuts and perms. The atmosphere on the ward began to change and soon the volunteers were responding to requests from these women to go out for dinner or on afternoon outings. At Christmas time, some of the volunteers realized that the women had bedrooms with windows without drapes. They went out and got drapes of different colors and on Christmas Eve, the men from the hospital’s engineering department stayed around after their shifts to put up the new drapes. Dean’s appraisal of the situation: “No medicines, it’s just that people behave like we expect them to behave.” This is the humanization process at work.

The Brooks family members were often directly involved in the lives of state hospital patients. There were times when his daughters made rounds with him. Patients frequently showed up at the Brooks’ house on the hospital grounds, which helped Dean’s family learn more about the experience of being a patient. They would inspect bathrooms, believing that said a great deal about conditions on the wards. One night, they found that the women in one unit were all sleeping in their clothes. When they asked what was going on, a staff person, Hazel Wiggins, asked them to take a look at the sheets.

The sheets came from the laundry department at the state penitentiary where they had been run through the mango, the device used for pressing sheets. To begin with they had been sloppily entered into the contraption first. They then returned them to the state hospital with all kinds of stiff wrinkles. The older ladies trying to sleep on them were so uncomfortable, it hurt them. Ms. Wiggins said that Mrs. Brooks should call the penitentiary and speak to them about it.

Mrs. Brooks asked Warden Gladden to bring some of the male convicts over to the ward. She soon had these tough guys in tears. As a result of this kind of family participation, it never happened again. The warden said that all these men had soft spots in their hearts for their mothers.

Following this, the warden asked whether there was anything the women prisoners could do at the hospital. Dean knew that units housing older people needed more nursing care so he asked for assistance and ended up getting personal care help from them. This worked exactly as he had hoped. This led to the program attended by both patients and prisoners. The training was essentially a continued nursing education class. A graduation ceremony was held for the female inmates and patients who participated. Because nursing homes were being built which took many state hospital patients, many of the women prisoners got jobs because of their experience on the hospital wards.

When he was asked whether he had ever been harmed by a patient, Dean answered no, even though he had. He denied he had been hurt because he did not want to fuel any more notions about the danger of being around people with psychiatric problems. In fact, there were four incidents in which he had been injured. He had a scar under his eye from a patient who tried to poke him with a sharp object. Another patient grabbed his tie but a nurse simply cut the tie off. A third patient struck him in the jaw and Dean responded by asking the patient, “Are you feeling better?” The fourth incident occurred at a Mental Health Association meeting where a patient started throwing some trays around and he got hit by one of them.

On another occasion, he was asked by an up-and-coming psychiatrist (who was later Oregon’s first mental health commissioner) to write out exactly what he wanted him to do. He took out a piece of paper and wrote, “Tell the boss when he’s wrong,” knowing that most people are more apt to please than anything else. He recognized that the “higher you sit, the more people think you’re well-fed and so you don’t get invited out for dinner very much.” He felt strongly that leaders should be willing to share when they had made mistakes and not be silent out of fear.

He would bring up his own mistakes to model what he was talking about. He told this last story many times. It involved a patient who had been mute for years. One day staff called Dean to the ward and when he got there the patient walked up to him with a smile and said, “Good morning, Dr. Brooks.” Dean was of course elated and told the patient how wonderful it was to hear his voice and how much he appreciated being told in person. They visited for a short time. Then, a little later, he got distracted and said to the staff (not realizing the patient was near enough to hear him), “Who dressed this man? These clothes are messy and dirty.” Turning back to the patient, Dean saw him walking away as the staff explained, “He did, doctor.”

No amount of apology and taking responsibility for his mistake could impact the patient. He never spoke again, leaving Dean haunted by this for the rest of his life. He broke down in tears every time he told the story, explaining that his distraction was his own fault of “trying to keep up appearances.” He challenged all to come to an understanding of personal biases in order to keep from harming others.

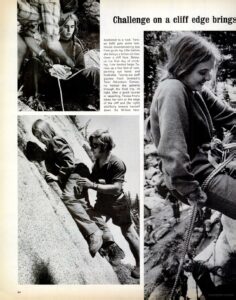

The Mountaineering Project

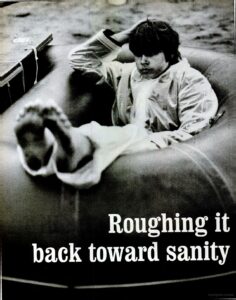

Probably the most innovative project that Dean created was the mountaineering program, which later received national attention as it was featured in a 10-page Life Magazine article in October 1972. This is a story of a dramatic reversal of the dynamics of dehumanization so characteristic of places like state hospitals. It offers proof that people who are patients have capacities far beyond their supposed “chronic mental illness.”

The program idea started one summer when Dean noticed that a group of Girl Scouts were trekking up and down the Blue Mountains in Eastern Oregon. He was familiar with this remote part of Oregon because he and his wife, Ulista, had purchased a summer cabin in the area. In asking around, he learned that the organizer of the Girl Scouts Camp was the legendary mountaineer Lute Jerstad, a member of the 1963 American party that climbed Mt. Everest.

The Brooks had been in Jerstad’s presence earlier when they were at the University of Oregon for parents’ weekend with one of their daughters. Jerstad taught there and was starring at that time as McMurphy in a stage version of One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. For later significance, this was the performance that changed Dean’s negative feelings about the book. He finally “got the point” of the story—that it was about power dynamics, not necessarily just about state hospitals.

The Eastern Oregon meeting resulted in Dean asking Jerstad if he would like to help plan a project where a group of mental patients would be team members with staff and go on a trip to the mountains in Eastern Oregon. Jerstad said yes, so in just a few months, 51 patients and 51 staff were on their way to an adventure that included whitewater rafting, mountaineering, studying ecology, hiking and just learning to “live off the earth.”

The patient and staff teams were divided into two groups of 17 each plus an observer and a doctor. The staff members were from all departments of the hospital and included psychiatrists, social workers, ward staff, secretaries, painters, mechanics, and others. The National Guard put up tents for the 16-day outing. None of Jerstad’s team knew, or cared, who were patients and who were staff. The experience ended up having a profound effect on how patients saw themselves. One patient shared “I’m not a patient, I’m a mountain climber!!”

Each group went their separate ways for five days. Patients developed meaningful one-to-one relationships between themselves and staff. In a dramatic reversal of the usual experiences in the hospital, there were times when rock climbing required a staff member, sometimes a doctor, to rely on a patient to get to the top of a rock and to rappel down a 100-foot cliff. This is obviously a dramatic example of a reversal of power relationships.

Another less dramatic but still significant kind of change was a patient who had always referred to a certain staff member as “the painter” but, on the expedition, began to call him “Bill.”

While the average length of stay for these patients at the hospital at the time was four years, within a year all but eight of the patients were discharged, four of whom were forensic patients whose discharge was not within the control of the hospital.

The biggest challenge was not the safety of the patients or staff, but raising the funds—which were never in the state hospital budget. Dean knew that he could not expect the state oversight Board of Control to which he reported to increase the budget for the project. But unexpected sources of funds came along, such as a card in the mail from a woman in Eugene who offered $2,000 to help fund the trip. Before long, other resources surfaced, such as when Bob Straub, then the State Treasurer (and later, Governor), stopped by and offered to call someone in Portland at the major philanthropic organization, the Collins Foundation. From this came the additional needed finances.

Other resources were secured for outfitting the patients and staff from a local business, Anderson Sporting Goods. The owner provided boots and other equipment at drastically reduced prices. Another local company, Salem Sand, arranged transportation, no small challenge in that patients and equipment weighed 10 and one-half tons and had to be hauled to Eastern Oregon by a semi. The Eastern Oregon city of Baker also welcomed all of the participants in the adventure.

One of Time Magazine’s major stockholders, Leo Adler, who was known as Mr. Baker, saw to it that a reporter was assigned to the adventure. Adler even visited the camp a few times and, at the end of the experience, personally hosted a rodeo and steak fry for 450 members of the community, all of whom had participated in some way in the expedition.

Dean believed that it was the development of one-to-one relationships between staff and patients that made the trip a success, and which he often referred to as the real healing power of the hospital.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

No matter how many innovations Dean Brooks made at Oregon State Hospital, he will likely be remembered by many as the man who figured out how to allow the movie to be filmed in the setting of the book itself—Oregon State Hospital. Before the decision was made, he had met with the producers, Michael Douglas and Saul Zaentz, and the director, Milos Foreman. He came away impressed with their integrity and vision for telling the story.

Maybe predictably, the state’s mental health bureaucracy was opposed to the filming, believing that only notoriety would come from it. Dean’s family has noted that at first he was taken by the stars he would begin to meet like Michael Douglas, Jack Nicholson, and Louise Fletcher. But his first step in considering whether he wanted the movie to be made at Oregon State Hospital was to ask patients personally what they thought. He went to every ward and asked them.

He was clear that if the patients did not want the movie to be made at the hospital, it would not be considered any further. But the patients told him they thought it was a good idea. They definitely were excited about the prospect of meeting Michael Douglas, the biggest star on television. It turned out later that, during the filming, Michael, with a key Dean had given him, regularly made rounds to visit with the patients and staff.

With the assurance that patients approved of the filming, Dean went ahead with the advocacy needed because the state’s mental health commissioner told him not to talk to the director of the movie. So, as a counter to that, Dean had his wife do it. With the dispute at an impasse, he and the state’s Department of Film urged Douglas and Zaentz to come to Salem and talk directly with the state mental health folks and the Governor.

They told the state people, “You can have the film shot somewhere else and they’re still going to call it Oregon State Hospital; and you’ll lose all the revenue that the film being made in Salem would have given you.” The movie was shot in Oregon State Hospital and, as everyone knows, it ended up winning all of the major Oscars, the second time in film history that had happened.

Dean made sure that the deal the state made with the film company included hiring patients to work on the film. The company hired 90 patients in every one of the film’s departments. A few were extras in the background of scenes. Some patients were dressed as doctors and nurses, with some staff dressed as patients. The producers made sure to premiere the film in Salem for the patients and staff.

Dean was invited to discuss the movie in many places all around the country. When he appeared on NBC’s The Tomorrow Show in New York City, he stated that “It’s about the use of power, for good or bad. It happens everywhere we have hierarchies—in junior high, banks, and NBC.”

A number of psychiatrists complained that the movie was “venal.” Some said that it was anti-psychiatry and set psychiatry back by 25 years. In spite of these accusations, Dean was invited to the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Hospital and Community Psychiatry for their showing of the movie in Atlanta in September 1976 in order to discuss the film. After the showing, he addressed the audience. He told them that a state hospital was the setting for both the book and the movie because of the difficulties encountered by everyone who deals with institutions of all kinds.

He pointed out that fiction “explodes into consciousness the things we have refused to look at” and that “no one who sees it can avoid responding in his or her own way to the predicament it exposes.” He told them that it is not a documentary, but rather an analogy, and that it should lead to focusing on “issues of denied rights…” which included the right to individualized treatment plans, the right to be free from undue chemical or physical restraint, the right to refuse treatment, and the right to informed consent. Dean concluded his remarks by urging those in attendance to discuss the rights of people, rather than to serve as film critics. He strongly encouraged them to contemplate their own facilities.

Radical Leadership

If this is not radical leadership, it is hard to imagine what would be. All of this from a state hospital superintendent who served 75 years ago. In spite of everything he had done to humanize Oregon State Hospital, he continued to express regret in my talks with him that many of his projects and innovations were lost when he walked out the door. Not surprisingly, though, he worked for many years after he left Oregon State Hospital advocating for change and the development of better community mental health programs. He was especially concerned about the increasing criminalization of people who were coming into contact with law enforcement, prisons, and homelessness.

Those fortunate enough to have known him and his work recognize that the fire burned until the end of his life. Dr. Dean Brooks still lives on in the inspiration he created for mental health services: to make it all about the people who are seeking help in their recovery process.

***

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations.

Tremendous Essay! Tremendous Man!!!

Report comment

I was in Dean Brooks hospital in 1969-70. While there I was never aware of Brooks coming into any wards, including those in my unit. I was also astonished when years later I learned there was a patient council — never heard of that either.

Regardless of his high-minded notions about psych drugs, everyone on my ward was heavily drugged on antipsychotics, regardless of whether we’d even shown evidence of psychosis or not. Those drugs were terribly depressing and debilitating, but nobody on the staff gave a rip about how you felt — if you refused to take the drugs, you’d be injected and quite likely spend a few days in solitary for not doing what you were told to do.

Brooks has a story about how he improved the ward clothing to make it more dignified — instead of wrappers he supposedly mandated real clothing. However I remember very well that in 1969, only two people on my unit were able to wear ward clothes that were actual clothing: a very fat woman and my very thin self. That was because the sizes we wore in clothing that dated back to pre-Brooks era were rather pretty dresses were the only ones that hadn’t been worn out. Everybody else, neither very fat or very thin, were stuck with the bathrobe-type wrappers purchased during Brooks’ tenure. He didn’t improve the clothing; he made it much worse. I still remember women clutching those inadequate wrappers to try to stay covered and warm.

In 1969-70, ward life was pretty similar to that shown in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest except that there was rarely any staff beyond aides on our unit. But the aides certainly lorded it over us n just like Big Nurse did in the movies. You did whatever they ordered you to do without hesitation or they would threaten you with solitary or with “talking to the psychiatrist about getting your treatment increased (the scariest threat because that meant even more of the disastrous drugs or even forced shock, a common punishment).

Those wanting a realistic picture of life inside OSH under Brooks should read Ward 81, which documented life on one ward there. The book ends with a nightmarish account of a woman who decided to refuse the drugs, intelligently citing their awful effects, and who was then utterly destroyed by forced shock, day after day, as ‘treatment’ as part of her punishment for that. Those who think Brooks was such a saint because he took 51 select inmates on a trip to the mountains once should read that (it’s online) to get the real story of what life in OSH under Brooks was like.

However there were some good aspects to the hospital. The food was pretty good. And almost all of us were on co-ed all-ages wards. Oregon State Hospital, to its credit, refused to form kids wards until forced to do so by the courts in the 1970’s, and I consider myself very fortunate to have been on an all-ages ward at age 17 instead of one of the kid-ghetto wards they were forced to create a few years later.

Report comment

The first and most important thing is that I want to honor the experience and perspective of the person who has described life on the ward as very different from that portrayed in my tribute to Dean.

Actually I think Dean would too. Evidence for that is the fact that the forward to the book Ward 81 is dedicated to him and Milos Forman. The reason for that was that he fully supported allowing the photographer access to the unit. To me this is a sign of a superintendent who did not want a coverup but instead wanted whatever was going on there to literally be pictured. I know too that he required full consent for the pictures to be taken and approved by the patients or guardians according to legal and ethical requirements. The state hospital museum which Dean was very directly involved in establishing includes information about the project and book.

Life and cultures in institutions are complex mixes of systems and have many risks. That was in many ways the main message in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The elements of these risks come from individual motivations, societal expectations and leadership.

This is why honoring the experiences of all, especially patients who have been there, is of critical importance. Not everything that happens in a state hospital is in accordance with the vision of people like Dean. I know this personally too from my years of responsibility for everything from the state hospitals to gambling addiction prevention. There are many things I wish I would have investigated and should have done differently. I am certain Dean would agree if we could ask him.

So I respect and honor the experience she describes so articulately.

Report comment

I agree, Grace. It’s nice to hear a “patient’s” perspective. Thank you.

Report comment

The field always needs leaders like Dean Brooks. Thanks for the story. I will add “well-written” with the explanatory note that I’m Bob’s younger (and shorter) brother.

Report comment

And may I add that when I say I’m Bob’s “younger and shorter brother” the difference is four inches? He’s 6’8″ and I’m 6’4″.

Report comment