Throughout my entire career as a therapist, I have battled with imposter syndrome. The idea that I am not good at what I do, that I am simply “acting” as a therapist. A fear that eventually I would get called out for my inadequacy and told that this therapist gig isn’t for me.

Because of this imposter syndrome I’ve experienced a lot of self-doubt. It both weighs on me and drives me at the same time. Especially when I was training, I never liked my self-doubt. It feels awful and I would get annoyed for not being in the present.

They say despite winning 7 world championships in Formula 1, Michael Schumacher continued to experience an intense level of self-doubt. Before he would step into his race car, the “what if” of losing all his ability to drive stayed with him throughout his career.

Michael’s story is something that resonates with me deeply. Thanks to recording my outcome statistics with my clients I objectively know that I’m a competent therapist. However, each morning when getting ready for work and on the drive to the office I have this niggle of fear—what if my therapist skills shut down during a session? Will I be able to help anyone at all?

This weight is never crippling, but I remember as a trainee I was convinced that to be an effective therapist, I had to be confident in my skills, like the great therapists who were training me seemed to be.

After I completed my qualifications, I was always looking for an antidote for my self-doubt. Like I was searching for El Dorado. Always looking to learn a new therapy or skill that would be the final missing piece to the puzzle. No matter what I pursued I could never shake that self-doubt. Always feeling I was the imposter, a fraud, on the run from the law.

It wasn’t until I started to read the work of Daryl Chow and Scott Miller that my views on the necessity of confidence started to change. Studies investigating therapist confidence have demonstrated that our confidence in our abilities as a therapist tends to grow as we become more experienced. It may be true that as we build confidence with competency, but does that same confidence help us improve? To go beyond competence—to become excellent at what we do?

The research is suggesting the answer is “no”; that while confidence increases with experience, therapeutic effectiveness does not. At least when it comes to striving for excellence, confidence can be a burden to improving one’s outcomes as a therapist. Instead, self-doubt is the true ally to the therapist that seeks to boost their skill and effectiveness. According to Miller, Chow, and Hubble, “self-doubt is associated with better decision making, work performance, leadership skills, greater self-control and tolerance, stronger alliance formation and superior outcomes.”

A hypothesis is that self-doubt impels us to look beyond our current abilities, whereas confidence has us believe that we already have all the answers we need. I remember what a relief I felt in learning that self-doubt could be helpful, since then it has gone from an enemy to an ally that I value greatly. This piece will be about how to effectively use that self-doubt to help improve your therapeutic outcomes with clients and pursue excellence.

Recently I wrote a piece with my views on the importance of seeking to innovate in the space of therapy. Now, I go a step further to suggest that to innovate we need to look at our weak spots.

We are trained to consider and look for our client’s weak spots but doing so doesn’t help us excel as therapists. We encourage our clients to look inside themselves, but how can we excel at teaching someone to go inward if we’re not willing to do the same?

At the end of the day, we do this job to help people. But how do we do that?

According to Miller, Chow, and Hubble, about 80%-87% of whether a client improves in therapy has nothing to do with a therapist. It’s based on “client-related factors” like their strengths, life history, pre-morbid functioning and situational influences (e.g., job loss).

However, the therapeutic alliance may be the most important therapist effect, which accounts for 5-8% of the outcome. In comparison, individual therapist factors such as personality and life experiences accounts for 4%-9%, building a sense of hope in therapy accounts for 4%, and the therapy technique or model used only accounts for 1% in influencing whether a client will get better.

In short, one of the most important things a therapist can do is try to strengthen their ability to be on the same page with clients.

This means that when looking at your own weak spots as a therapist, it would be a safe bet to first consider how you can improve your skills in developing a stronger alliance.

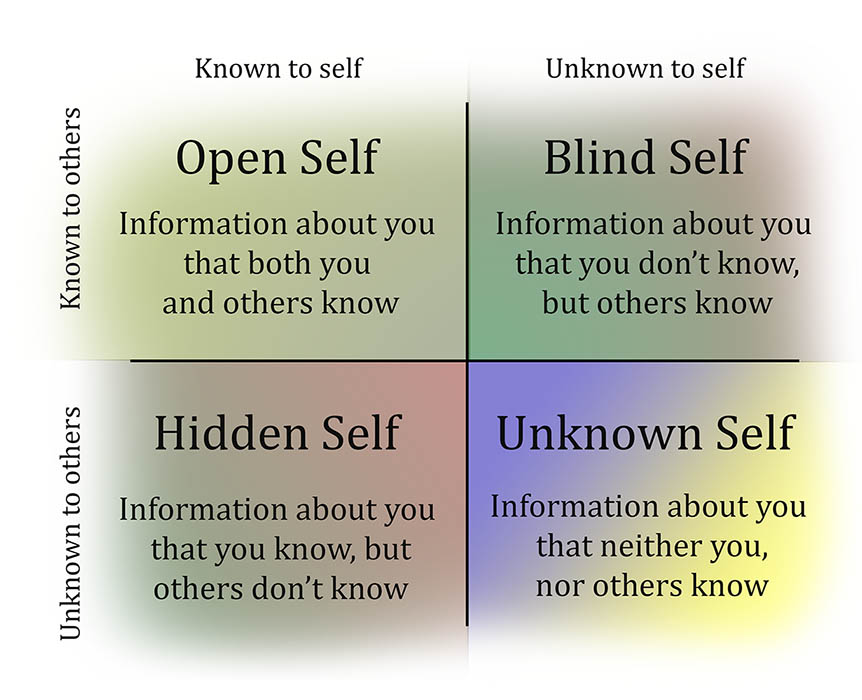

So how does one look towards their weaknesses? I think of “Johari’s window” from my early undergraduate training, Johari’s window is a theory that focuses on understanding what we don’t know about ourselves. I think that to improve our weaknesses we need to not only have a willingness to look through the window, but also to step through it.

We cannot get to the other side of our weak spots until we are willing to go through them.

We cannot get to the other side of our weak spots until we are willing to go through them.

For many of us, it’s natural to want to avoid looking through our weak spot window, either out of fear that we’ll get stuck in the window or that what we find on the other side will be too much to handle. Avoidance and hesitancy are natural human reactions. This is where I feel my training to become a therapist could have better focused on encouraging me to make room for and connect with my self-doubt, instead avoiding it by pursuing confidence in counselling techniques and strategies.

I want to be clear about what I mean in referring to weak spots, as it may be natural to think that I’m referring looking at ourselves on a “big picture” level, to consider what therapy modalities you would be well served to learn in order to improve. Undertaking a course in therapy tends to include learning a number of skills and new concepts across a short period of time. For instance, when looking to improve my skills, I may decide to take up a course in schema therapy, which covers a vast array of information to not only help me understand how schemas work but also how to understand them in clients and strategies to help heal them.

Instead, when referring to weak spots, I’m referring to looking at the small picture, to really zoom in and look at the finer details of how you work. The idiosyncratic and automatic behaviours you engage in that impact how you do therapy. I’m often looking at ways to improve on the “over-explaining” and “fix it” modes I can get myself into during a therapy session. I may have never realised I had these tendencies if I stayed focused on the big picture of how I work.

Why do I think taking the effort to look at the small picture is so important? Because you can learn all the treatment modalities you like; you can learn ACT, CBT, trauma therapy and many more. The possibilities are endless. The problem is that learning at the big picture level will do nothing for your effectiveness if they do not address your small picture weak spots—and how can we know if such training is addressing our small picture weak spots if we are unaware of them in the first place?

My belief is that to improve our skills, we must look at the small picture of our weak spots first, because those idiosyncratic behaviours that currently sit outside your awareness will always act as a barrier to addressing the bigger picture of your skills. I can learn all the ACT therapy I like, but that’s not going to stop me from my over-explaining tendencies.

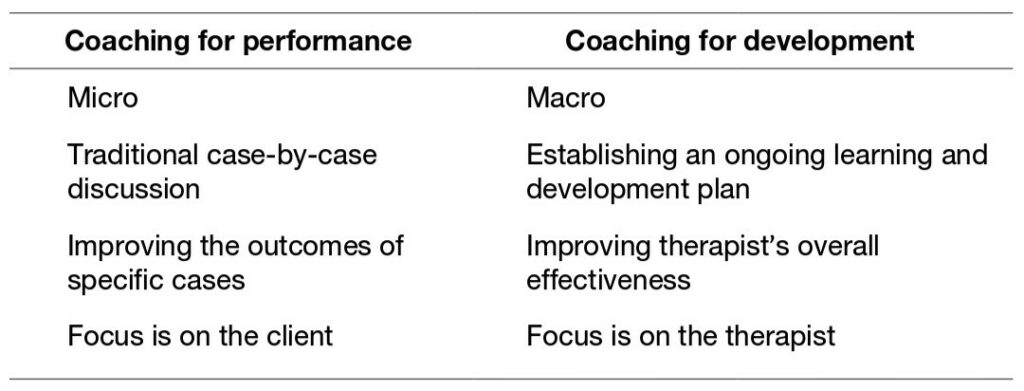

You might be thinking, “Well, what about supervision? Surely that helps me improve my outcomes?” Once again, the research is suggesting that this is also incorrect, as unfortunate as it is. Daryl Chow has put forward the argument that how we currently undertake supervision is coaching us to “perform,” whereas to improve our effectiveness we need to engage in coaching to “develop.” The table below is a handy rundown on the difference between these two coaching styles.

So, in traditional supervision (i.e., coaching for performance) I’m more likely to talk about one client case at a time and how I can use a particular kind of therapy to help that client. The focus is also far more likely on how I can get the client to change. Whereas in coaching for development, I’m likely to be encouraged to investigate and address my idiosyncratic weak spots. I’m therefore more likely to improve my overall effectiveness by focusing on a behaviour I can improve across multiple clients at one time. Therefore now in supervision, I’m unlikely to bring up a single client case, unless it is urgent; instead, I’ll bring up weak spots I feel I need to address in myself.

So, in traditional supervision (i.e., coaching for performance) I’m more likely to talk about one client case at a time and how I can use a particular kind of therapy to help that client. The focus is also far more likely on how I can get the client to change. Whereas in coaching for development, I’m likely to be encouraged to investigate and address my idiosyncratic weak spots. I’m therefore more likely to improve my overall effectiveness by focusing on a behaviour I can improve across multiple clients at one time. Therefore now in supervision, I’m unlikely to bring up a single client case, unless it is urgent; instead, I’ll bring up weak spots I feel I need to address in myself.

I’m not saying that learning a new kind of therapy or having macro-focused supervision have no use whatsoever, only that they are unlikely to improve your therapy outcomes with clients or patients beyond where they stand now.

My message is a simple one. We have our self-awareness spotlight pointed in the wrong place. Look at the small picture, before looking at the big picture. Look inside yourself, before looking outside.

Widening the Window

There are a few strategies we can consider to help us go through our weak spot window. Many of these have come from what I have learnt in the pursuit of creating my own system of deliberate practice.

One very simple strategy that you can consider is to sit down with a pen and paper or your computer and have a good old fashion brainstorm of your weak spots. It doesn’t matter how many or few you come up with. Brainstorming was the first strategy I used to launch myself into this journey of tackling my weak spots. In case it helps, it can be useful to think of your sessions with clients in phases. For example, the start of a session, the middle, and the conclusion.

If brainstorming doesn’t prove helpful, that’s ok, there’s another strategy at hand: The Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities in Psychotherapy. This tool was developed by Scott Miller and Daryl Chow. The taxonomy will help you explore five important domains that influence therapy outcomes and to consider how you perform in each domain using a self-rating system. It will also encourage you to create goals that are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-related (SMART goals). There is also another version of the taxonomy that can be completed by a supervisor, if you have one that knows your work well.

While working on my own system of improvement has been important, there is no way that system would have been effective had I not had outside help and guidance. Seeing what others do is integral for helping me expand my own awareness to generate new ideas. Otherwise, I’d just be existing in a vacuum.

If you also see value in sharing ideas to help us all improve, Nathan Castle, a fellow psychologist I know (my Deliberate Practice coach) is working on developing a new training format for innovations in therapy. Below is a link to four quick questions asking about innovations you have developed in therapy practice. Taking part would not only allow you to share your own innovative ideas, but to learn from the innovations of others. As the answers to this survey will be used to develop a unique training showing off the innovation’s professionals are developing to improve client outcomes in their practice.

Nathan’s details are in the intro to the questionnaire if you’re curious and want to ask him for more information: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/6XMG22K

On the note of sharing, some of you may be curious on what weak spots I am working on right now. Currently I’m practicing some skills to address my “over-explaining” mode. I have a tendency to give clients lots of detail when providing psychoeducation. Providing detail can be great at the right time for the right person, but it can also be overwhelming at the wrong time. It can even give me a headache if I’m not careful.

I have decided that it would be useful if I can encourage clients to share their understanding of concepts before I start or continue an explanation. The idea being that I don’t need to keep explaining if they already know something well—saving us both time and energy.

There are two techniques I am using to help clients share. The first is that before I start psychoed on a topic (for example compassion fatigue), I’ll first ask the client “so, what’s your understanding of x?” If they are unsure, I’ll encourage them to take a guess. The second technique is similar, in that I’ll check in with a client as I’m providing psychoeducation, by asking, “What’s your understanding of what I’m saying so far? I want to check that I’m making sense.” Doing this gives me a stronger indication as to whether I need to deepen my explanation.

I’ve had some early success in asking the above questions; clients have pleasantly surprised me in how well they are following my line of thought and sometimes they reflect on something I never would have considered. It gets them to do more of the leg work, deepening their experience of themselves and I lessen my chances of mental fatigue. Everybody wins!

There have been some significant impacts for me in learning to turn towards my weak spots. Not only have I built confidence by having a greater acceptance of myself—warts and all—but this journey has also fostered a belief that I have the ability to design a system to take on just about any weak spot, even outside of the therapy space. Say hello to “bicycle repair man”! I’m kidding, but it has fostered patience with myself, something I really value, in being ok to take it slow in addressing one small weak spot at a time. There’s also power here for clients as well, as I believe that by sharing my weak spots and showing a willingness to be vulnerable, they are in turn empowered to tackle their own perceived weak spots.

There are many potential gains in being willing to look at your own vulnerabilities, something I’d love for all therapists to experience. You deserve to be empowered by your weaknesses, not confined to avoid them. So, I ask you: What do you have to gain by letting yourself look at your weak spots?

I want to mother everybody.

I see what you are building, like with wooden blocks, and I want to admire your fascination with what you are creating.

The truth is people are endearing but also boring, and this is why therapists make up fabulously precise techniques, to brighten up the session. I equate it to shamanistic whirling capes and smokey guttural incantations. A magic. Humans like doing magic and having magic lift them free of despair. On and on the intimate session goes, from since the baths in Rome, to the woodlands of medieval Finland, to the confessional box in Ireland, to the student campus, the same lovely tete a tete. Someone wants to cry. Someone is there to tell them it is good to cry. Life is hard. Help is needed.

In these jagged brittle times where it is becoming tricky to speak with ease everyone is feeling lack and loss. Loss of being held in the bosom of understanding.

The computer is damning us all….BIG TIME.

There fast approaches a day where we will all realize how bad the computer is to the vulnerable mortal man.

Report comment

Great article.

I think part of looking inward– and seeking development instead of performance– is to get abandon the idea of being a ‘successful’ therapist in the more commercial sense.

Make a decent living, don’t strive to be wealthy or well-known. Don’t try to get ‘your name out there,’ in terms of either commercial or academic notoriety. You can’t be looking inward if you’re trying to sell yourself.

I’m not sure exactly what Diaphanous is getting at, but the computer, and the online world, does encourage us to be self-promoting. Hopefully, more and more of us are turning away from that– our own version of turning on, tuning in, and dropping out without the acid.

Thanks for this.

Report comment