When I was 3 years young, I saw my dad hit my mom. It was the first time but not the last—one of many traumatic moments I witnessed growing up, and one of many reasons why I’ve devoted my life to healing. And helping others heal, too.

We were living in Puerto Rico, where I spent the first years of my life. I was born there in 1993 and raised from age 5 in Rochester, New York, to mostly Latin culture and traditions. One of them being: mental health equals “crazy.”

For a long time now, Puerto Ricans have had a negative association with seeking out help for their mental health. When I was growing up, older generations simply associated it with being mentally and/or emotionally unstable and in need of inpatient care. “Loco” means “crazy” in Spanish, a anyone who treated a “crazy” person was a “loquero”—kind of like what “shrink” represents in English. Therefore, anyone who visited a loquero was deemed crazy.

That tradition was continued in my household and family. As recent as 4 years ago, when I asked my dad why he didn’t seek help for his drug addiction and mental health, his automatic response was, “Yo no estoy loco!”—that is, “I’m not crazy! ”

As a child, I had simply absorbed the belief as well. The first time I saw a therapist, I was in juvenile non-secure placement. I was 14, and I had come to peace with the fact that I’d be away from my home and family—for the first time ever—for a full year. But I was not at all happy that I was forced to see a therapist. My first thought, just as it was engraved in my heritage, was: “I’m not crazy!” But it was mandatory, so I sat there with my hot cocoa and a therapist, answering all the questions with either “everything is fine” or “I’m great.” It wasn’t until the age of 27 that I voluntarily sought out help myself and was okay with receiving my own diagnosis.

That would have not been possible if it weren’t for all the training I received and work I’ve done as a Peer Specialist at Compeer Rochester, a small organization that focuses on mental wellness through friendship. During the past five years I’ve spent time rewiring my brain and erasing generational curses. Which, in turn, has helped me understand many aspects of my life, my mother, and even why my father is an IV drug addict.

From a young age, my only role models were everything I didn’t want to do or be. My mom’s side of the family, the aunts and uncles I first grew up around, who always had something to fight about. I was around 7 years old when my mom went to prison for selling drugs to sustain my sisters and me as a single mother. The next two-plus years we stayed with my father and his ex-wife, someone I came to love and respect dearly. Sadly, those were the only years that I have positive if vague memories of my father being “sober.” Although always strict, he was a hardworking man and tried his best to give us love and affection his own way to the best of his ability.

Once back with my mom upon her release, my sisters and I had attendance issues throughout elementary and high school, which caused a lot of phone calls from school and Child Protective Services, and eventually led to my probation in middle school. That’s how I entered the juvenile criminal system: I literally got probation for not going to school.

Some may judge my mom for not being tough enough, and, heck, for a while I did, too! But it turned out that my mom was struggling with her own childhood trauma and untreated bipolar depression. The oldest daughter of 13 kids, she was taken out of school in fifth grade to care for her siblings, cooking, working, bathing them all, and completing household duties while my grandparents also worked to provide for them in 1960s Puerto Rico.

After that, she had to grow up quickly—and from the age of 9 onward, no longer received affection from her mother. She instead was reprimanded while raising her siblings. She was blamed for everything, was physically abused, and was forced to marry, until she ultimately ran away at the age 15—the same age she made her first suicide attempt. She carried all this trauma throughout adulthood, seeking counsel in drugs and alcohol for a long while, something she concealed fairly well.

Treatment with kindness and respect

Here in the States, she had sought out mental health treatment but found no support system. Why no support system? Mainly because of the lack of bilingual services and resources.

But she looked for help anyway because, even though she grew up with all these misconceptions about mental health,, she bravely understood she had to be mentally well in order to raise her daughters in a stable environment. I remember taking the bus with her and my sisters multiple times to go to her therapy appointments. I was young,, but I remember the last time she went; she had a dispute with the staff at the mental health office. She argued that she was fine, and there was no need for us to be removed from our household and away from her. She probably told the therapist she was overwhelmed and wanted to die, and, well, that’s a red flag to providers—something I know now from the training I’ve had. We left the therapy that day and mom was visibly upset, mainly because the providers thought she couldn’t support us. Which in some sense could have been true. I firmly believe our mental health determines how we function and deal with life. The healthier our mental health is, the better we treat and love ourselves and others.

So, she had tried to seek help—but the language barrier, economic barrier, and flaring symptoms discouraged and triggered a setback, and my mother didn’t seek treatment again for more than 15 years, her main reason being the lack of bilingual providers who can relate. She confessed to me she felt misunderstood and out of place, and that no one took the extra step to empathize and understand her culture.

And just to clarify: When I refer to “treatment,” I do not mean treated with medication, I mean treated with kindness, respect, and acceptance—because everyone is an individual with rights and purpose. Yes, medication works for some, but I actually believe that doctors over-medicate people, taking away their essence and persona rather than actually getting to the ground cause of why they feel and act in a certain way. Some professionals fail to recognize that meds and gaslighting are not the answer, and that supporting, reaching out, showing respect, honesty, and consistency doesn’t hurt—and is very much needed everywhere.

These days, my mother is doing better. Without alcohol and substance abuse, she eventually found refuge in faith, and also her children. Occasionally she struggles with her mental health, but she has a much broader understanding of it and why it is so important. But at the time, all of this unacknowledged and untreated trauma—my mother’s, my father’s—was unintentionally transferred on to my siblings and me. We witnessed bickering between them for years as we grew up. They were separated and still blamed each other for everything that went wrong with their children. My mother would blame my father for preferring drugs, lying, and not being present to help her throughout our adolescent years, which was when everything really started going downhill. My father blamed my mother for telling us he was on drugs and for not taking care of us “correctly.”

I was 12 when I last witnessed a physical altercation between them, at 2 a.m. on a Saturday. My father was dropping off my little sister, and for some reason, he and my mother began arguing outside the house next to my dad’s parked car. My dad threw a blow at my mom, and her head rebounded from the light post, which made her furious. When he struck again, pinning her head against the light post, my mom bit his finger so hard that all I saw was my father jerk back with blood gushing from his hand. My mother stood up for herself that day, and my dad finally understood he had no right to put his hands on her again.

I still loved and love my dad—even now, when he’s unrecognizable due to heroin. It wasn’t until four years ago that I learned about the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) score questionnaire and began to understand his distance, substance abuse, and, sometimes, his lack of empathy and attendance to fatherly duties. I learned about the ACE score during a training session, and I took the questionnaire myself and scored 4. I remember silently wiping away my tears in a conference room full of people—because all I could see was my dad on drugs.

Generational trauma, stigma, and inequity in care

I always wondered why my father did drugs and preferred them over his kids, even after people tried to kill him on different occasions—stabbing him with an ice pick on his clavicle, giving him drugs laced with rat poison, hitting him with a car for owing drug money and then a bat.

I remember this latter incident because he came looking for my mother’s help and refuge. I saw the bat lashes and bruises marked all over his back and body. I heard him tell my mom what happened because at this point, he no longer cared about hiding the truth. My mother would still help him because he was our father. After that, I remember him sleeping in the basement and in the car in our yard, alongside a tiny shed and garage.

He would come by periodically, not to be with us but to hide or heal—and then leave for months until he needed help or to regain strength again. He roamed North Clinton Ave in the mid-2000s and was even seen eating out of McDonald’s garbage bins. He was taken out of Rochester by his younger sister in fear of him losing his life, and for some time he was in recovery—only on suboxone, a pill to replace heroin. Which was okay, I guess, because he wasn’t shooting up. But he depended on it, and when he could no longer get the prescription legally, he turned to the streets once again. The price of suboxone in the black market was equal to or greater than a bag of heroin, which convinced him he’d be better off getting the real thing. He was also convinced he could control it

When I saw him slipping back to his old habits in 2011, I decided I would no longer be too scared to speak up, and I told him how I felt. I told him how it pained my sisters and me that he always preferred drugs over us, and how I would hate to see him in the streets again. I told him this and, on some level, internally judged him for it because I couldn’t understand. Never had I asked about his childhood, but fast forward a few years with my new knowledge and perspective on the ACE score, when I personally asked him: How was his childhood growing up? It was a random, general question he stated no one had asked him before.

I remember his face, and its distant look full of surprise, pain, and regret. My dad disclosed that his real father abandoned his mother with two kids. He grew up getting beat up and verbally put down and witnessing his mother getting beat up and verbally abused by her boyfriend, too. Defenseless due to my grandmother’s alcoholism, he spent a lot of time neglected, fending for himself and ultimately being the one to raise his sister, two years younger, while still a child himself. He had no real role model, and all was chaos. He had his first child (my half-brother) at the age of 17, his second child (my older sister) at the age of 19, me at 21, and my little sister at the age of 23. He never really received love and affection from his parents, and therefore didn’t know how to give what he didn’t receive. He was a broken person, then and now, who had decided to not seek help but rather use drugs as his coping mechanism. I kept track of his answers and took the ACE questionnaire for him. The score was 9.

I don’t excuse him, but I can empathize with him—now that I’ve had my own battles with opioid abuse, and now that I better understand the effects of childhood trauma on mental health. Working as a Peer Specialist has made me reflect and recognize what my parents and many other untreated and under-treated minorities all have in common: Generational stigma, trauma, and inability to access professional care that is not condescending, biased, and full of language barriers. It’s hard to find a person who genuinely cares.

Lived experience as the key to helping others

You may wonder: How did that young Puerto Rican girl who very much disliked seeing a therapist when locked up in the juvenile system end up working in the mental health field as an adult? Simple answer: I wanted to help youth in crisis. And it was meant to be.

In 2008 I was 15, back home after my year in detention, when I joined Monroe County’s SWAT (Spreading Wellness Around Town) youth council and entered a poster contest for the Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health. I also attended their conference in Atlanta, Georgia. Having learned in placement what it means to have a support system and be surrounded by positive and stable people, I attended the conference with an open mind, deciding to not look at mental health through a negative lens.

I won the poster contest, I got $500 in prize money, and my art was displayed in the U.S., Puerto Rico, and Guam during mental health awareness week 2009. The win was a fresh accomplishment following all the honor rolls and awards I’d earned while in placement. Still, after a few months back at home, I went downhill for a while, smoking weed, feeling hopeless and helpless, avoiding social connections, hating the world and myself. But after three years with very poor school attendance and drug use, drowning in my own pity and making bad decisions, I remembered who I was and I got back up, graduating high school with a regent’s diploma after five months of hard work that included summer school.

I did this because I remembered my potential and chose to act on it, eventually becoming a Youth Peer Advocate (overseen by New York State’s Families Together: Youth Power) with Compeer Rochester. The nonprofit, linking mental health with community, focuses on connecting kids and adults who have a diagnosis—and are in outpatient care—with a mentor who can help with resiliency and rehabilitation, making it their goal to embrace mental wellness through friendship. To clarify my role at Compeer, I was not a volunteer but a hired Youth Peer Advocate (YPA) for Compeer’s new fee-for-service program.

So, what is a YPA, also known on paper as a Youth Peer Specialist in Training (YPST)? It’s a new, nontraditional way of assisting youth in crisis and doing firsthand, preventative work. The goal is to assist youth alongside a support system—often care-managers, family, school, and community—to help diminish a youth’s chances of ending up in lifetime mental health care, criminal justice, or long-term crisis.

Often confused with Medicaid’s Psychosocial Rehabilitation (PSR, or Skillbuilding), the Youth Peer approach is similar but definitely NOT the same. Let me explain a little further. A Skillbuilder and a Youth Peer Specialist in Training (YPST) both work on established goals, usually for three to six months on a weekly or biweekly basis, to help participants with current barriers in their home, school, or community. Both are highly encouraged to work alongside and build a support system. But that’s as much as it overlaps. Differences between PSR and YPST are subtle but grand. PSR is usually provided by anyone who’s trained and has a high school diploma, plus two years’ experience working with youth. YPST work can be provided by a person without a high school diploma—but with firsthand, equivalent life experiences in the system or systems, and who is now actively resilient or in recovery. The belief is that lived experience cannot be taught. All the other professional and textbook stuff is taught later on, through mandatory training.

As a member of the NYS Youth Peer Advocacy Advisory Council and also a mental health service provider for more than five years, I am aware that YPAs are a needed instrument, and yet, due to the approach’s short lifespan, it is not completely understood—and peers, like Skillbuilders who do the hands-on work, are often overlooked and underpaid. As I always explain to my participants during my initial visits, and to anyone who asks, a YPA is not a therapist. Not a counselor or psychiatrist. Not a teacher or family member. A YPA is a credentialed person between the ages of 18 and 31 with experience in the educational, criminal justice, and mental health systems, enduring substance abuse, trauma, poverty, or other life factors.

And that experience can be synonymous with the experience of a youth who needs a role model, mentor, or friend.

Breaking the cycle

A YPA has lived and endured navigating these systems that most of the time, especially among the minority communities, are discouraging and unfair. Peer Advocates are not here to fix you or be judgmental. We’re here to redefine mental health services, offering them not in a traditional office setting but in a home, community, park, mall. Anywhere the participant feels most comfortable, as long as work on the established end goal is being done. It is designed for peers to assist, encourage, motivate, validate, guide, and brainstorm as well as be a role model and friend, mentor, teacher—and to live alongside you in the most eye-to-eye, genuine way possible. A Youth Peer Advocate is meant to meet you where you are in a non-condescending way, as both a professional and a human being.

YPAs are also in the middle of their own growth process alongside participants, which is why we’re also called Youth Peer Specialists in Training. As I previously mentioned, the main difference between a Skillbuilder and YPA is that the YPA has gone through similar situations and recovered, coming out resilient and therefore possessing one of the most important factors, besides trust and respect, that no other type of service provider can provide: the RELATABLE element.

Take me, for example. I had some childhood trauma of my own. My mom was a single parent who got incarcerated for selling drugs, and then we lived below poverty line. That caused me to feel ashamed and embarrassed in school. We never went to sleep hungry, but there were many times the snack before bed was not what we desired. There were times I had to hand wash my jeans and clothes in the bathtub because I had no clean clothes, and mom had no money or transportation to a laundry place. I used the house heaters in winter to dry my clothes, and sometimes cheap soap to wash my hair. By the late teens I no longer lived with my mom and started to dab in opioid pills. I was addicted to them for a long time, until I got tired of being tired. That alone was a journey itself.

Sharing relevant life experiences is encouraged in this field in order to bond, have empathy, and connect. Therefore, a participant can feel more encouraged to seek assistance and feel that they’re being heard and understood rather than just being told what to do by someone who has no idea how life really is for them outside 30 minutes in some office. It’s important to add that these services are also given as Family Peer Support for parents and guardians in need, provided by Adult Peers for Adults, with the same purpose of relating through personal experience.

I am proud and at peace with all I went through: From being the middle child and growing up in a single-parent household, to having a father in and out of my life because he’s addicted to heroin, to seeing my older sister struggle as a teen mom at the age of 14, to witnessing constant altercations and physical fights between family members, to encountering drug dealers and drug users everywhere I went, to being locked up in juvenile detention, to dating older men and surviving my own journey of substance abuse, mental health struggles, and attendance issues at school—after all of that, I found the willpower to change. Getting diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder three-plus years ago finally helped me understand some eras of my life.

All that hardship made me the woman and advocate I am today. Once I joined Compeer Rochester, my focus has been to educate myself on mental health and, in turn, to help break the mental health stigma in the Black and Latino communities. To do outreach. To expand knowledge and resources. On May 2, 2022, I was recognized by the New York State Office of Mental Health for my life experience and the genuine work I do with youth and young adults in Monroe County, helping them navigate and understand the importance of mental health.

Some people choose to give up and give into their situation because they lose hope—and ultimately end up passing along bent and broken childhood dreams and nightmares to future generations, labeling them as normal or cultural traditions. Others want to be or do anything that is different from all that they grew up in and around with, realizing that only they can be the change in their life. Only they can fight the fight, make the sacrifice, and make peace with the past in order to leave it behind. Only they—we—can break cycles. And that goes for any culture.

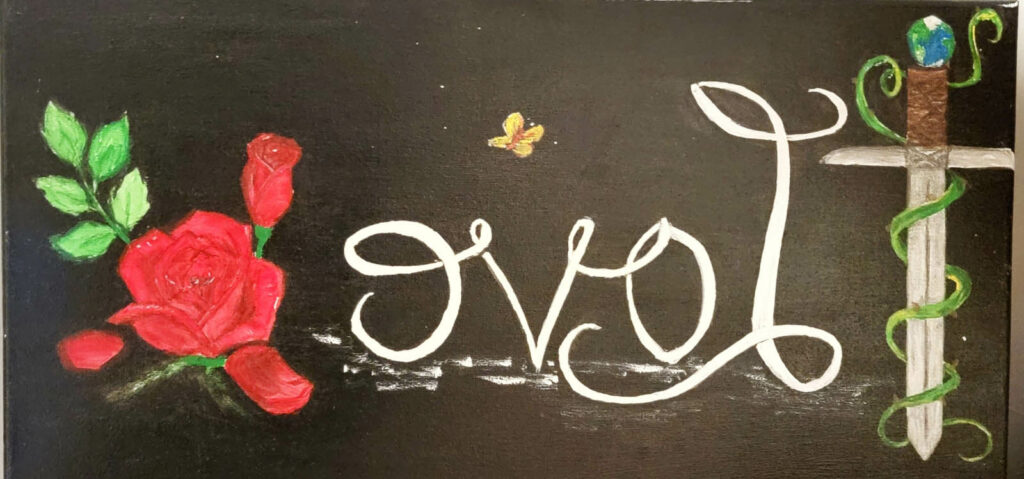

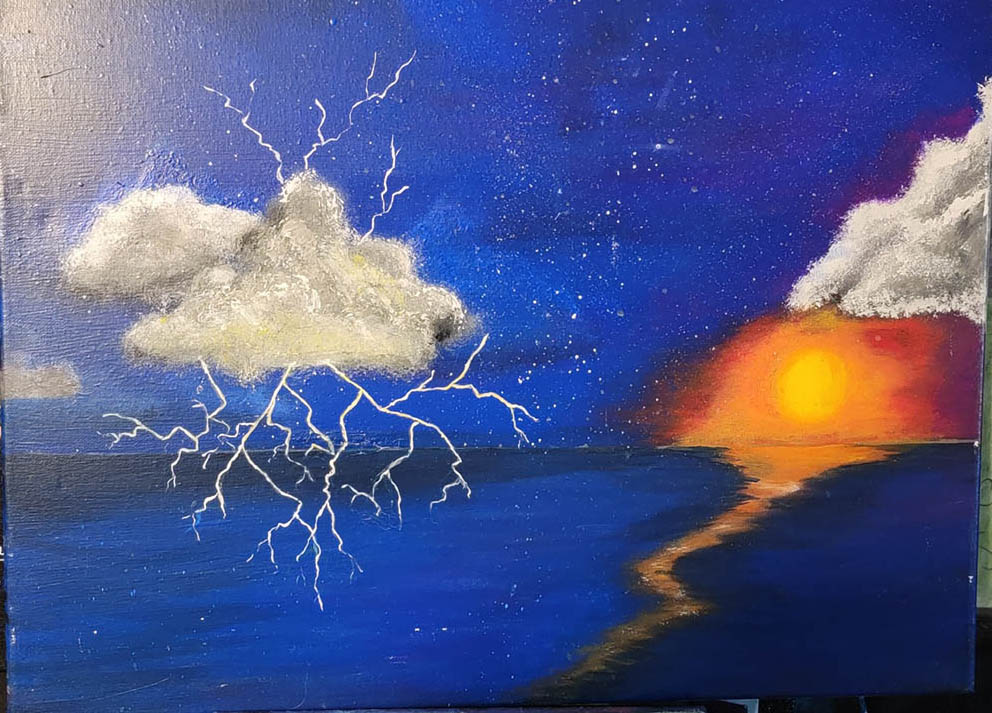

I decided to make peace with my judgments and accept my father, whatever state he is in. But I don’t lose hope that someday he will be that man I barely remember. I am proud of my mom, because she did what she could with what she had. And at the end, everything happens for a reason. Me, I’ve decided to take refuge in my two little girls, Pheanix and Zaphyre, and my fiancé. My coping skill to overcome that faded pit is art. It’s always been art, and my authentic mirror writing. Now I make mirror-written paintings and hope to sell my art worldwide.

I’m dreaming big, but my purpose is to wake people up to these cycles, because sometimes all you need is a genuine person to help you stand up when you are down and reignite not the light at the end of the tunnel, but the light within yourself. Self-love and self-awareness are key to a healthy life.

I chose to break cycles. And I’m still breaking them. You can too!!!

PS: We need more Peers!!

Top featured image also by Angela Colón-Rentas.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from The Thomas Jobe Fund.

This is such a beautiful blog. Thankyou for giving such hope!

Report comment

Technical note: The images are displaying backwards.

My teacher was very aware that “aberration is contagious,” especially from parents to children. This starts, according to his research, even in utero. He outlined in 1950 the mechanism he thought was responsible for this “contagion” and how to treat it – to break the cycle.

Unfortunately, his ideas and methods remain largely unknown and un-discussed today. Sure, kindness, respect, and acceptance can go along way. To the extent that we are all “peer advocates” for somebody, it is something that everyone should learn to do. But this mechanism – which counselors and therapists don’t even know how to practice on themselves – would be a big help along this line, yet we remain conveniently ignorant of it.

Report comment

Yes, these are examples of her “mirror writing” artworks, so they’re meant to be backwards.

Report comment

“….sometimes all you need is a genuine person to help you stand up when you are down and reignite not the light at the end of the tunnel, but the light within yourself. Self-love and self-awareness are the key to a healthy life.”

Yes!!! THIS is the way to heal broken hearts, minds, lives and relationships, NOT name-calling (diagnoses) and “psychiatric medications”.

There’s nothing better than help from someone who’s been there and sees you as capable of helping yourself.

Report comment

This article explains how having a support system of peers can be a key factor in ending the cycle of trauma. Increased resilience and better mental health are only two of the many positive outcomes that have been linked to peer assistance, which the author describes in detail. This text is informative and helpful for anyone interested in the subject.

For More Info:- https://michaeldadson.info/about/

Report comment