“Everyone should be in therapy.”

It’s a sentiment I heard just about every day when I was in graduate school to become a therapist. But it’s also something I hear now from friends, acquaintances—even stand-up comics.

Should everyone be in therapy?

It’s a difficult proposition to test. Those who don’t think they need therapy, or who don’t think therapy is useful, are not particularly likely to go to therapy. Any study of therapy’s usefulness, therefore, contains only people who need therapy (or think they do) and who already think therapy is helpful—the very people for whom therapy is probably useful (or for whom the placebo effect is largest, since they expect to improve in therapy). Existing studies generally focus on people with specific psychiatric diagnoses, and usually those who have pretty severe symptoms.

“Everyone should be in therapy” is a statement that assumes a lot. First, there’s the neoliberal assumption that no matter how good you’re doing, no matter how content or even happy you are, there’s always something you should be working on. And then, even if there is perhaps something you could work on, the assumption that therapy can help. For instance, there’s a meme floating around the internet that “men will do anything but go to therapy.” But has there ever been even a single study testing whether therapy can reduce toxic masculinity or promote healthy masculinity? (Answer: Not that I could find.)

There’s really no evidence base for the idea that “everyone should be in therapy.” But proponents will also tell you that there’s no real downside. Therapy can only help, so why not give it a try?

But is that so? There are some obvious harms: wasting your time and money, of course. But researchers since the ‘60s have noted that therapy can also cause psychological distress, problems with existing relationships, and even relaxation-induced anxiety and panic. Even our current darlings, like mindfulness, can lead to increased anxiety, pain, and dissociative states like depersonalization and derealization.

Proponents of therapy argue that many of these effects are transient and that the positive effects of therapy overshadow these potential harms. And some of these issues may even be positive, like conflict in relationships because those undergoing therapy have grown in self-confidence and gained a clearer picture of what they want from life.

Ultimately, though, we have been in desperate need of better data. Do the benefits outweigh the harms? And is there a difference in the risk/benefit ratio for those with severe mental health difficulties versus those without?

Now, we’re lucky enough to have gleaned some new evidence to address this very question. The only problem? It doesn’t bode very well for the proposition that “everyone should be in therapy.”

Better Access

Beginning in 2006, Australia implemented a program called the Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists and General Practitioners through the Medicare Benefits Schedule initiative (Better Access). The program was designed to enable more people to use mental health services, particularly psychotherapy, by making these services more affordable through the use of rebates. (Notably, users still paid over $70 per session as a co-pay, on average, so it is unclear how well this strategy worked.) Other parts of the initiative were designed to increase therapy use in rural areas, for instance through the use of telehealth services.

A new report, led by researchers Jane Pirkis, Dianne Currier, Meredith Harris, and Cathy Mihalopoulos, provides the data from 10 interconnected studies of Better Access. It’s designed to allow us to see how well this initiative has served the public.

They write that in 2021, 10% of Australians interacted with mental health services through Better Access, and half of those received psychotherapy. On average, those that received treatment went to more than five sessions of therapy.

Younger people, women (about two-thirds of the patients were women), those living in cities, and those who were at least middle class or wealthier were far more likely to receive Better Access services. This means that, as with most psychotherapy research, participants were those most likely to believe in psychotherapy and believe that they need psychotherapy.

However, one of the strengths of the Better Access studies is that there were many people with no psychiatric diagnosis or with mild symptoms who did access care. Thus, we can see how people with few mental health problems fared when compared with those who had significant mental health problems.

There are also two limitations, though, to keep in mind with the data collected from the Better Access studies: We still don’t have any information about people who would choose not to pursue psychotherapy on their own (for instance, most men). If urged to engage in therapy, would this group gain any benefit? Based on this data, we can’t tell. The other limitation is that there is not a comparison group who did not receive treatment, such as a placebo or wait list control group. So, any improvement that we do see in this study could just as easily be due to the placebo effect or other factors.

Better Access—Better Results?

Although there were 10 interrelated studies conducted using the data from Better Access and presented in the report, most of that data doesn’t tell us much about actual outcomes. For instance, the first two studies were meant to assess how many people used Better Access and what traits those might have (including the demographic information mentioned above).

Several studies, which focused on interviews and survey data, found that people who volunteered to talk about their experiences with Better Access described themselves as having good outcomes—which is not surprising, given the self-selecting nature of these surveys (those who answered the questions might be those with the most positive experiences) and the potential for bias (in which respondents answer the way they think the researchers want them to respond). Other “studies” included meetings about what to do next and an interview on what providers and referrers thought about Better Access.

However, some of the studies did provide more objective data. The study listed as “Study 2” (the third study in the packet) provides the clearest picture of the outcomes of the intervention. It included 83,346 “episodes of care” (slightly later in the study, they refer to 86,121 episodes of care; it is also unclear if this means separate individuals or not).

This study included data on 11 different commonly-used outcome measures. On all the measures used, baseline severity was the best predictor of success. Those who came into therapy with severe psychiatric symptoms tended to improve, while those who came in with no or mild symptoms were more likely to get worse after treatment.

“Irrespective of the measure used,” the researchers write, “those with more severe baseline scores had a greater probability of showing improvement over the course of the episode. Conversely, those with the least severe baseline scores were the most likely to deteriorate over the course of the episode.”

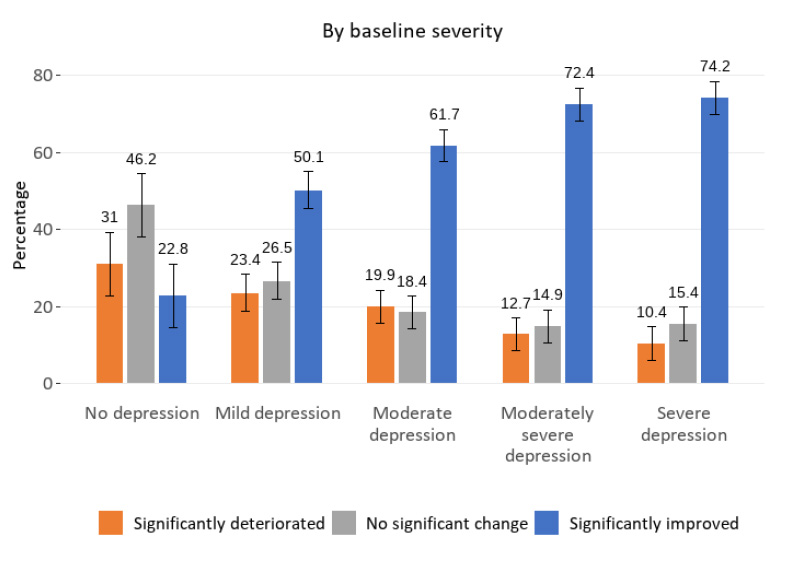

This is told quite clearly in the graphs that accompany the report. Take, for example, this graph of PHQ-9 scores, one of the most commonly-used measures of depression severity:

About a third of those that came in to a therapist without depression “significantly deteriorated” compared to the average (or, one might say, “developed depression after getting therapy”). Less than a quarter improved. Then, in a pretty linear way, the scores align themselves more toward expectations as the severity of scores on the PHQ-9 increases, until, for moderately severe and severe depression, the vast majority of patients—about three-quarters—improve after therapy, and relatively few deteriorate.

However, we should remember that a lot of this improvement after therapy could be due to the placebo effect. In a recent Cochrane review that mostly focused on severe depression, the placebo effect was 42%. That is, almost half of people with severe depression got better without receiving any actual treatment.

Pirkis and her colleagues conclude that most people benefit from therapy—but that those with no or mild symptoms are at higher risk of deteriorating in therapy than improving. If you don’t already have depression, you’re more likely to develop it in therapy than you are to receive some benefit.

“It is worrying that consumers experience deterioration in their mental health in not insignificant numbers of episodes, and that some show no change. These consumers are most likely to be people who began their episode with relatively mild symptoms or high levels of functioning or satisfaction with life,” the researchers write.

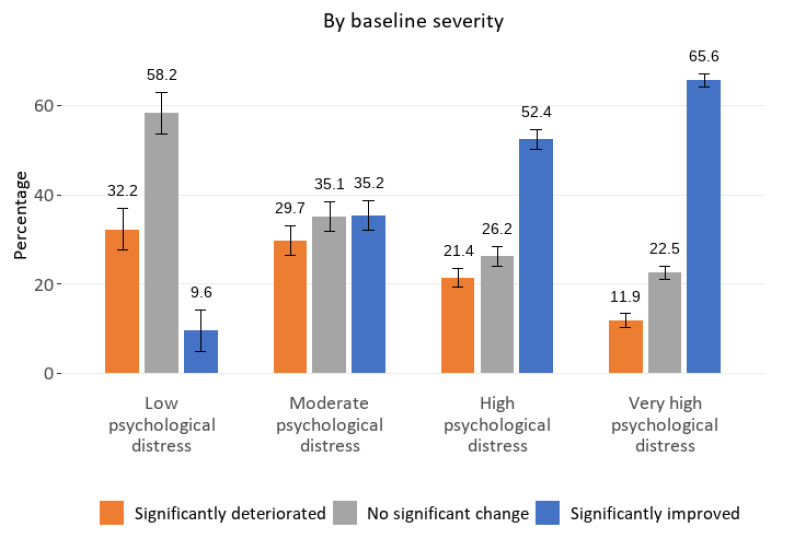

Finally, take a look at this graph of the K10, measuring overall psychological distress:

You can see that people with low distress are about three times more likely to be harmed than to improve in therapy. Even for moderate distress, outcomes are evenly distributed between deteriorating, staying the same, and improving.

If three people with moderate distress go to therapy, they’re rolling the dice: One will feel worse after therapy, the second will be wasting time and money for no result, and the third will feel better.

In an analysis of the report published in Australasian Psychiatry, researchers led by Stephen Allison write:

“The mass rollout of brief psychotherapies for milder conditions does not appear to reduce population distress or suicide rates, and a considerable proportion of these patients experience deterioration.”

They add,

“Instead of the mass rollout of brief psychotherapies for milder conditions, prioritising longer courses of psychotherapy for more severe conditions may minimise risk and maximise the potential benefits of the Better Access initiative.”

Conclusion

In the end, the average improvement and deterioration doesn’t tell us much because of the lack of a placebo control group. I think it’s likely that the placebo effect can account for at least some of the differences in improvement seen here, but that’s up for debate. Without a control group, we can’t be sure.

It would be reasonable to assume that a combination of these explanations is at play here: Therapy can cause some people to deteriorate. Sometimes people just have a poor therapist, or aren’t a good fit. Moreover, therapy might bring up anxieties, trauma, stresses that the person already had under control, and might interfere with the ways the person was already dealing with those issues.

As Stephen Allison and his colleagues write, “Offering treatment for milder symptoms might undermine personal coping abilities and social support networks.”

For other people, therapy may be very helpful. Certainly, many people feel that therapy has been helpful for them. This may be especially true for those who have specific diagnoses or severe distress.

Yet, at the same time, therapy may not be as powerful as we think, and much of the improvement we see could be due to the placebo effect.

Ultimately, even if we take this data at face value, the story this data tells is that those with low distress—those who are relatively happy and content—are more likely to deteriorate than improve when given psychotherapy. Even those with moderate distress (as shown in the K10 graph) are about equally likely to improve, deteriorate, or stay at the same level of distress.

Thus, this data answers one specific question pretty clearly: No, not everyone should be in therapy.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from The Thomas Jobe Fund.

Why are some people so fixated with “data”? Have they no intuition?

I’ve always considered the statement, “everyone should be in therapy” extremely presumptuous and equally irritating. But so are most of the people who make that statement, which most of the time are “therapists” who love sticky-gooey therapy culture which strangely contrasts with their “data” fixation. And why have so many things gotten worse in a world increasingly saturated with “therapy” culture?

People don’t need “therapy”, they need to be listened to, but not by self-important fools who live and die by “data”.

And in case you were wondering, there IS such a thing as too much data:

“Why, Yes, There Is Such A Thing As Too Much Data (And Why You Should Care)”, by Elick Eizenberg at forbes.com

Report comment

Correction: sticky-gooey-loopy therapy culture.

Report comment

The world’s “data” fools need to ask themselves the following question—but WITHOUT searching for their beloved “data”:

Why do so many things keep getting worse in a world increasingly fixated on “therapy” and its habitually biased “data”???

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

I remember a book called ‘The Centerfold Syndrome’ that showed that therapy can be quite effective at addressing toxic masculinity. Of course it was written by the therapist himself so doesn’t qualify as research, but there might be some in the references

Report comment

What’s the best therapy?

Not letting other people tell you how to life your life — which should include, first and foremost, any godforsaken “psychiatrist” or “therapist”.

Report comment

I find your dismissive and even derogating attitude toward data to be confusing, unconvincing, and even disrespectful. Intuition has its place and can be of value. It even has been found to be a useful or sometimes even valuable source of information and guidance in facilitating healing in effective forms of therapy. However, reliance on intuition alone is a notoriously unreliable means of supporting generalized statements, such as the assertion that “many things in the world keep getting worse in a world increasingly fixated on ‘therapy’ and its habitually biased data”. That may indeed by your experience and, based on that you may have developed an opinion. It may even be what you intuitively believe to be so. However, there is nothing compelling in what you assert that would convince me or other people that this sweeping condemnation of I therapy (and apparently your negative opinion of psychiatrists and therapists) is irrefutably true or shared by others. Certainly it was not shared by a number of individuals in the study who reported that they experienced improvement based on their participation in therapy. And that raises another important issue. The “data” that you summarily dismiss is not a bunch of numbers crunched by the researchers. Instead it is information based on the experiences of individuals in the study. It wasn’t manufactured or “spun” by the researchers, but reported by them based on what individuals in the study reported to them. Just as I would not presume to invalidate what your experiences and feelings about therapy are, so too I would hope you would not invalidate the experiences and feelings of a large number of people in the study. This is what I find disrespectful when people dismiss “data” as it is essentially a form of violence on the experience of other human beings. It would not only be dangerous but impossible to live in a world in which all data is to be mistrusted and disregarded. That is because when all is said and done, a good deal of data is actually indispensable facts that when rely on. For example, your post and my post would on this site would not be possible in the absence of data used by our computers and the internet. Are there facts that therapy can be either useless or even harmful? Yes. Are there equally facts that therapy can be beneficial? Yes. We may disagree on the reasons why, but even then those reasons hold no water in the absence of data to support them.

Report comment

[Duplicate Comment]

Report comment

I find nothing compelling in what you assert, nor am I trying to convince you or anyone else of anything — I’m simply expressing my views. And I find your dismissal of my views on intuition disrespectful, and I didn’t need any data to come to that conclusion.

Report comment

By the by, it’s amazing how ingeniously man and nature has evolved over the many millennia, without ever glancing at anyone’s “data”…

Report comment

Exactly. Human beings survived for a long time before “data”!

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Removed for moderation

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

Sometimes people’s devotion to data-related minutiae just makes life all the more complicated and misses the point, and for no good reason. (It must be in their DNA.)

“Life is NOT Complicated” – from Alan Watts on Youtube

“Why Do We Insist on Making Everything So Complicated?”, from stevetobak.com

Report comment

I am a great lover and believer of the work of Alan Watts. He wrote a book that had a profound impact on my understanding of psychotherapy and the nature of healing, entitled “Psychotherapy East and West”. In that book, Watts makes a powerful and detailed case that psychotherapy–when practiced in a manner first informed by the timeless truths of the great wisdom traditions and second by a clear understanding of the roots of many forms of psychological distress and suffering in socialization by a sick society. I firmly subscribe to both of these points. The following quote by Watts speaks to how psychotherapy can be–and is–a means to liberation: “In almost all of its forms it [psychotherapy] has one enormous asset: the realization that escape is no answer, that the shudders, horrors, and depressions in which ‘the problem of life’ is manifested must be explored and their roots felt out. We must get rid of the idea that we ought not to have such feelings, and the relatively new Existential school goes so far as to say that anxiety and guilt are inseparable from human life; to be, consciously, is to know that being is relative to nonbeing, and that the possibility of ceasing to be is present at every moment and certain in the end. Here is the root of angst, the basic anguish of being alive, which is approximately the Buddhist duhkha, the chronic suffering from which the Buddha proposed deliverance. To be or not to be is not the question: to be is not to be. Because of anxiety man is never fully possessed of what Tillich calls ‘the courage to be,’ and for this he always feels guilt; he has never been completely true to himself.” Watts also held the thinking and work of the psychologist, Carl Jung, in great regard.

Report comment

Unfortunately, a great deal of what passes for “psychotherapy” these days does not incorporate any of the important philosophical underpinnings you mention above. A lot seems to now be focused on “neurobiology,” on DSM “diagnoses,” and on compliance with “medication” and other “treatment plans” like DBT or CBT. I did therapy for a number of years in various settings, some formal and some informal, and saw and heard what others were exposed to by their “therapists,” who in my view did not deserve the name. I’m not sure they are even taught about unconscious motivations or ideas of consciousness or striving or attachment or awareness of one’s own process, let alone touching on the existential issues of the bizarre expectations and abuses of modern society. The focus seems to be on making “symptoms” go away, as if “depression” or “anxiety” were the problem rather than the observable manifestation of the actual issues causing distress. This is the inevitable result of “DSM” thinking – reducing the complexity and spiritual richness of human experience to “desirable” and “undesirable” emotions or behavior, which the therapist and/or psychiatrist is tasked to change, by force or manipulation if needed. It is small wonder that folks faith in psychotherapy as you describe it is very low – very few people seem to ever experience it these days!

Report comment

I didn’t go to therapy for a East/West philosophical treaty. Every “theory” my therapist threw at me took me further from understanding. I entered therapy after receiving a clue that my mother-daughter relationship was kind of freaky, expanding into an exploration of my chronic misfit state, surviving as a self-effacing woman in a world of grandstanders. Had my therapist lectured me on existential angst, being and not being and Alan Watts, my head would have spun around on its axis. My angst stemmed from my Monday morning problems. I saw little existential angst in the louder, bolder types around me.

My therapist’s “theories” removed us from my life, emotion and experience.

Now, with decades of perspective, I see my problem as one of social hierarchy, how I stationed myself as low on the totem pole and shrunk from dominance signaling. My current state is a little less recession, plus my knowledge that my timid perspective and vulnerability are the special ingredients I bring to the discussion.

From my viewpoint, many problems stem from social hierarchy, being one-down as someone’s child and student, growing up to work for the man. Therapists, whose job seems a performance of posing as the wise shaman, are antipodal to us who believe in shaman’s power.

There mere process of engaging in this authoritarian-supplicant exercise enforces its distortion. Nor did I care how well-read or philosophy-steeped my therapist was, if he failed to guide me into solving my Monday morning problems.

Being in a space with this angry defense of therapy through a philosophical lens only reinforces my feelings why it can be useless or harmful.

I wish clinicians were capable of checking their egos, their neediness to be the smartest one in the room, at the door.

Report comment

Some thoughts on intuition:

“Intuition is a very powerful thing, more powerful than intellect…This [intuitive] approach has never let me down and has made all the difference in my life.” – Steve Jobs

“The Intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant…All great achievements of science must start from intuitive knowledge…At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason.” – Albert Einstein

From “Steve Jobs and Albert Einstein both attributed their extraordinary success to this personality trait”, by Ruth Umoh, from cnbc.com

Report comment

How did humanity survive prior to the advent of data? It seems to me that humanity was better off before the time that people said things like, “Studies show…” in order to win an argument.

Many of us who survived abusive therapy and abusive psychiatry were shamed for trusting our gut, trusting in ourselves and our own perceptions. We were called “lacking self awareness” and “lacking good judgement” or flat out “crazy” for believing things like, “these prescribed drugs are making me worse.”. We were laughed at.

Well, it turns out we were right: the data shows that more people are harmed by psychiatric drugs (some of them severely) than are helped.

“Data” about these drugs was used against us, to our extreme detriment, by “experts” who insisted that the drugs were safe and effective and if we weren’t “better” it must be due to our mental illness being too severe or that we were non-compliant. “Data” has been used in ways that caused tremendous harm and now we’ve come to learn that the data was ridiculously flawed and biased and that actual fraud was committed.

Psychiatric survivors have every right to mistrust data. It’s not like anyone has apologized to us for the harm that was done to us based on fraudulent data.

Report comment

Wow. This rant supports my confirmation bias that the mental health profession, as a group, skew toward incurious, scornful, defensive authoritarians, and I’m thankful to escape their thrall. How interesting that the clinicians I see in these discussions run to their scolding and battle stations rather than hold the slightest curiosity about a tattered consumer. (Maybe this explains why the literature of iatrogenesis is so thin.)

It’s hilarious that mental health providers scoff at intuition, since I saw nothing except intuition in their practices. Intuition is a polite word for spitballing, I suppose.

Data? How do you quantify the quality of a human life, and where and how do you collect this data? Had I fed your statistics, during or shortly after my so-called treatment, I too would have checked the enthusiastic boxes, colluding with my provider who pumped me up cooing sympathy, victimhood, and simplistic nostrums for my life’s improvement. How beatifying to receive the oracle’s advice! Too, I had to justify my time and money. Only after I distanced from this did I realize I’d be scammed by a performance artist and was duped enough to hand her the weaponry of my vulnerability. AND, I fulfilled her need to be a rescuer and authority rather than receiving any quality help. That was my therapy. That wizards are all pretenders.

I implore the clinicians here to dismantle their authoritarian reflexes, relax their defensiveness (try deep breathing!) and truly respect and hear the complainants on these threads.

Our at least examine why these threads gouge your defenses. Is it so much more comfortable to tra-la down a self-deceptive path?

Report comment

Thank you for posting this interesting and informative discussion of the study on the effectiveness of therapy. It is balanced and fair in discussing the findings. I was particularly impressed with the number of participants and therapy sessions involved in the research. Expanding access to mental health, in general, is a good idea. Particularly since, as a rule, those with psychological and emotional problems often are unable to get care or are unable to afford it. This sadly in particularly true in the U.S. which has suffered for many years under a two-tier system of health care with priority given to medical conditions and psychological conditions often going unidentified or untreated. The research on psychotherapy effectiveness does say that the placebo effect or the belief of individuals in the efficacy of therapy explains a part of what leads to positive change. The other key variable consistently identified as predictive of a positive outcome is the quality of the relationship provided in therapy. For example, that the therapist and client (for lack of a better word) both trust and like each other, they agree on what issue or issues are to be “worked on”, and they agree on the methods used to be used. This is sometimes called a working alliance. Another variable not as easy to quantify is the person of the therapist him/herself which not surprisingly is an important factor in determining the quality of the relationship. This variable is generally found to be more important than years of experienced or type of training. I think of this quality as being essentially the capacity of the therapist to demonstrate compassion, a sense of genuineness, and an ability to be as fully open to the lived experience and world-view of the person seeking help while also holding out the belief that one’s suffering can be transformative. These factors were not examined in the study. Also it seems to me that individuals who may not be experiencing a problem or a low degree of distress may be mistakenly seen by therapists as having a more serious problem than is actually the case, being unmotivated, or being overly defensive. This is because of the tendency unfortunately for mental health provides to over-pathologize the people who come for treatment. This can certainly lead to the negative outcome found in the study. Finally, I want to let you know that neoliberalism has had a definite adverse impact on how mental health is understood and how treatment is provided. When therapy becomes a commodity, negative consequences can be expected.

Report comment

“Therapy” doesn’t become a commodity; it IS a commodity. That’s why it’s called “therapy”.

Report comment

No use dancing around the truth: whenever you charge a fee for something, it becomes a commodity.

Report comment

I prefer “free therapies” offered among friends and within communities.

Report comment

I think we’d be living in a much healthier culture if people weren’t made to believe they need pay-to-play “therapy”.

Report comment

I agree!

Report comment

The other thing to keep in mind with the Pfizer funded nonsense that is the PHQ9, that has been shown to inflate ‘depression’ prevalence’ is that the ‘scores’ are manipulated in myriad ways. After all its generally the therapist that administers the tick box and then inputs the data themselves. Given most services use these scores to pressurise, stress and ultimately burnout out therapists it is in the therapists interest to manipulate the scores down and this actively encouraged by management. Or they inflate the scores at intake and reduce them over time and presto ‘recovery!’

I have had people tell me that past therapists have essentially cajoled and bullied them into revising the scores down. In fact in many services they ran ‘recovery workshops’ that were all about manipulating the scores down eg – I see you’ve scored a 3 here but didn’t you tell me you went out last week…so would this be closer to a 2? Stuff like that, do this a few times and people either get the message or double down.

We also have an impoverished, really meaningless measure of ‘recovery’ so its all smoke and mirrors – this ladies work is good on the same service in the UK https://thefutureoftherapy.org/iaptsurvey

William Epstein in three key books has also dismantled the research base for therapy and finds there is none and it can be harmful – be great to see a review of this three books or an interview with him – the illusion of psychotherapy, psychotherapy as religion and psychotherapy and the social clinic – all good reads.

Report comment

“When therapy becomes a commodity, negative consequences can be expected.” Well, “therapy” today has most definitely chosen to become a “commodity.”

Most, if not all, therapists have chosen to become non-medically trained people, who funnel healthy, well insured people, off to the scientific fraud based psychiatrists, despite the scientific “invalidity” of psychiatry’s DSM billing code “bible,” since all psychologists have chosen to bill according to psychiatry’s “invalid” “bible.”

https://psychrights.org/2013/130429NIMHTransformingDiagnosis.htm

“Ultimately, even if we take this data at face value, the story this data tells is that those with low distress—those who are relatively happy and content—are more likely to deteriorate than improve when given psychotherapy.”

But, of course that’s the case, since “psychotherapy” today is really nothing more than non-medically trained people defaming people they do not know, with the iatrogenic scientifically “invalid” psychiatric DSM “disorders.”

https://www.amazon.com/Anatomy-Epidemic-Bullets-Psychiatric-Astonishing-ebook/dp/B0036S4EGE

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxidrome

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neuroleptic-induced_deficit_syndrome

So no doubt, “those who are relatively happy and content—are more likely to deteriorate than improve when given psychotherapy” … when psychotherapy is only about funneling innocent, non-“mentally ill” people into psychiatry’s massive iatrogenic illness creation system.

When, in reality, very few, likely, suffer from psychiatry’s iatrogenic illnesses, unless they are put on psychiatry’s iatrogenic illness creating drugs.

Report comment

I don’t think everyone should be in therapy – for obvious reasons. But there are lots of different things a person can do to help a worried mind.

Report comment

I like online jigsaw puzzles.

Report comment

Birdsong, what about this one.

John Crace.(Journalist)

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2022/may/23/i-feel-totally-seen-john-crace-on-how-guided-breathing-soothed-a-lifetime-of-anxiety

“…After 65 anxious years, trying every conceivable treatment and therapy available, just one session of breathwork was all that was needed to calm a troubled mind..”

“….I was first diagnosed with depression and anxiety in the mid-1990s, though in hindsight it had dogged me through much of my adult life …”

Report comment

Fantastic article, Fiachra. And walking barefoot on grass can be helpful, too: “Earthing: The Benefits of Being Barefoot”, by Fiona Austin @welldoing.org

Report comment

Or this one here…

Recommended for Healing Trauma – Eckhart Tolle

https://youtu.be/dZ2GfrendQg

It Works!

Report comment

So Australia as Well as the UK has mass publicly funded therapy. Why is this happening? That us a bigger question. In the UK IAPT was rolled out to get people on benefits due to psychological distress back to work. It was thought to be of monetary benefit to the state as people in work pay taxes instead of receiving benefits. I have not read of any proof that it worked. It was rolled out under the Blair/Brown government and continued and possibly extended under the Tory governments after 2010 when other mental health services suffered cuts and sectioning, ie locking up under the mental health act, increased. Meanwhile as inequality increased, as it has since 1980, the number of people who are anxious or miserable enough to justify mental health diagnosis increases, as does consumption of psychiatric drugs, proportionally to inequality. Equality decreases as trade union membership decreases, Thatcher got in power determined to squash the unions.

Perhaps mass therapy is the bit of psychological comfort the state provides to distract from the emmiseration of extreme capitalism in addition to the mass drugging with Prozac.

Why would we trust the state, whose main job is to maintain and facilitate capitalism, to relieve us of our misery when capitalism is a major cause of that misery?

Report comment

I don’t like anyone who capitalizes on people’s misery for a living.

Report comment

At its most basic level therapy is just having someone to listen to all your BS. It’s pretty easy to see how that would be beneficial to someone’s mental health and probably why people with healthy social relationships aren’t lonely and have better mental health. What makes a therapist effective is often more about life experiences or natural personality traits rather than any clinical training. The necessary life experiences are often the kind of experiences that disqualify people from advanced training and may explain why peer to peer counseling shows such surprising efficacy.

Report comment

For me the most therapeutic thing was stopping “therapy”. I find talking with intuitive people on an equal footing in the real world much than better than having to accommodate a therapist’s huge ego and overbearing psychic space, which was what I needed to get away from in the real world.

Report comment

The question “should everyone be in therapy?” is misleading. The better question is “does everyone need help from time to time? The answer is yes, but…

“Therapy” is just a fancy word for emotional support, which imo shouldn’t come with demeaning labels, a soul-sucking “power imbalance”, and most of all some god-awful fee, all of which add insult to injury, goddamn it.

Report comment

Peter, thank you for this thoughtful and interesting article. These findings are fascinating and I appreciate your critical analysis. I’d like to add three thoughts.

First, regression to the mean helps explain why people with higher depression scores were more likely to show “significant improvement” in depression when reassessed later. Basically, higher scores are more likely to change because there is more room for improvement. This is not necessarily attributable to the therapy “working” or not. As an analogy, novice golfers who shoot high scores would be expected to show significantly more improvement after working with a professional golf instructor than experienced golfers who shoot low scores regardless of the quality of the instruction.

Second, therapists are not magicians who can wave a magic wand and make clients feel better when their life is falling apart around them. I’ve had clients who were initially mildly dysphoric become devastated in the context of a catastrophic life event like a divorce that happened during our work together. In such cases, it’s not necessarily fair to use change in depression scores from baseline as an index of therapy “working” or not – something more akin to the client being able to function adequately and solve problems while being highly distressed is a better outcome. Therapy is often erroneously marketed as a quick fix where people can learn “effective techniques for feeling happy,” and undoubtedly many therapists focus on such techniques in their work. Real life and real psychological wellbeing don’t work this way. I have no problem believing a handful of therapy sessions consisting of superficial feel-good “skills” without honouring the complexity of life and working on its challenges in an authentic way can be unhelpful or worse. What happens when the quick fix turns out not to work and the obviously false narrative behind its promise is revealed?

Third, I think the title of your essay asks a great question (“Should everyone be in therapy”?), and these data and your analysis offer a compelling answer: “No.” In my view, life isn’t meant to be lived in doctors’ and therapists’ offices though it is good to know they are there when needed. Personally, I think our society would be in much better shape if psychiatric drugs and psychotherapy were replaced with physical exercise for 90% of mildly dysphoric people who would otherwise enter the mental health system.

Report comment

I cannot be the first to think of this, but isn’t the data discussed here most compatible with a “regression to the mean”- interpretation? People tend to dance around a ‘mood baseline.’ When their mood is up, it is more likely to come down again. When it is down, it is more likely to go up. No guarantees, though.

When I look at the graphs, it seems to me that for these Australians, the baseline lies somewhere in between no depression and mild depression, and at moderate psychological distress, and that you then see the effects over time you should expect when therapy is statistically irrelevant across the board.

Report comment

Obviously the original statement, “everybody should go to therapy” is hyperbole. Yet the author appears to suggest that it may do more harm than good. I watched hundreds of couples after a session when they entered with furious anger leave their session and see them in the parking lot through my office window giving each other long, passionate, loving embraces. I also saw people on the verge of panic attacks leave feeling relaxed and confident. Research into therapy results are quite unreliable. David Busch, LCSW, (retired relationship and trauma therapist at Se-REM.com).

Report comment

I wish therapy would expand beyond traditional options. Talk therapy isn’t the only therapy. And which modality are we “talking” about anyway? CBT, DBT, ACT, Jungian, peer-led?

ADD coaches or personal coaching would likely be more useful to me. But they’re not covered by most insurances. I’ve never understood why.

In personal coaching, you set concrete goals linked directly to well-being outcomes: better physical health, financial independence, positive familial interactions. You create habits to automate those things regularly being worked on. How is this not more effective therapy than endless navel-gazing & focusing more and more on your own BS?

Report comment

With the overwhelming majority of therapy these days being cognitive (top-down) and symptom-focused, these results are hardly surprising. No doubt I’m biased here, but I believe that differentiating based on modality would show substantial variations in effect, and bottom-up approaches such as IFS and EMDR would be shown to be far superior.

Report comment

The ethical foundations of the therapy process represent a significant area and a potential blind spot. Therapy operates as a scientifically informed means to reinforce a “collective” mentality, considering psychological methods and their research as part of the broader social sciences. However, research indicates that this collective or universal approach often falters when confronted with trauma, as trauma represents the boundary where universality ceases. To effectively aid individuals in recovering from trauma, it is imperative to recognize the importance of collective support and social bonding.

Therapy can be viewed as a commodity that provides individuals with a space for social bonding. However, the mere act of financial transaction within therapy diminishes the value of social bonding. Additionally, the unconscious nature of the transactional aspect in therapy poses a problem. Discussing the purchase of a therapist’s time may challenge the therapist’s sense of ownership over providing care, thereby creating a fundamental issue at the core of the therapeutic process.

And this is one aspect of the foundational issue. However, I want to add that therapy does work when a therapist is strong enough to speak about this glaring issue and makes it conscious so both therapist and clients do not lose sight of the reality of the therapy…I think Freud was not shy about this but somehow with the attachment theories, the transactional and the commodity part of therapy became hidden. This allows “forever therapy” and loss of capital for the client and creates unsafe space for some. Imagine if the client could bring up how much they spent the year and talk about that – most therapist would give a new diagnosis to the client or dissociate completely! Another reason I believe this is an issue is the area of consent. Most therapists become writers and talk about their clients and earn money on those stories but never provide a cut to the client. This can continue to harm clients. Most clients in therapy (this is my opinion) would have hard time saying no to consent to their stories becoming extra income for therapists because again the dynamic of the therapy process.

Report comment

The financial transaction in so-called “talk therapy” was bad enough. What really got to me was the infantilizing “power imbalance” bullshit.

Report comment

Charging fees for listening to people is the biggest scam going.

Report comment

Thank you, Peter, for this thoughtful article on these Australian psychotherapy studies. I think that it is very important that more people know that psychotherapy often is not very helpful and can be very harmful. These days most people think so highly of psychotherapy that it is difficult to trust yourself when you see that it doesn’t work for you. I wish I had known of results like you present here before I was in psychotherapy. I would have been able to protect myself better.

However, I would like to see more articles on the question of how people with chronic mental distress do get better. For me it wasn’t just one thing that helped, but it was an intensive mix of yoga, Buddhist meditation, self-help groups, social anxiety desensitisation training, a training in communication and conflict skills to just name the most important ones that I had to commit myself to over several years. And all of it together made a huge difference in the end. And none of them would have sufficed on their own.

I know that there is not a lot of research that apporaches the question of mental health from the side of the recovered. However, I know that there is some research and I’d love to see more of it covered at Mad in America.

I remember vividly that Bessel van der Kolk in his 2014 The Body Keeps the Scar gives a brief summary of 40 years of research in trauma-oriented psychotherapeutical approaches for people who have experienced ongoing abuse and neglect in childhood and experience moderate to high mental distress. And contrary to the aim of the book he states that psychotherapy is not working. But because he is a believer he goes on to recommend it anyway. But he says something else there too that I found most important because it is just what I have also done and what has led me to a full recovery. He says that there is some data that shows that of the above described group those who show the best improvement to their mental health have two things in common. They take their recovery journey into their own hands and do yoga or a similar practice that helps them to calm, center and unify body, heart and mind as their foundational practice in their recovery and for their daily well-being.

Interestingly, it is just the same what David J. Morris in The Evil Hours. A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder concludes after studying the existing body of research to understand what is best for adults who have had life-threatening experiences and suffer from mental distress similar to what is described under the post-traumatic stress syndrome.

I’d appreciate it a lot if you could go more in that direction at Mad in Amercia too. It is not one thing that we still have to find and then can offer people to recover from their mental distress but it is a mix of a 1000 different beneficial things that people have to find and that involve all areas of life.

Report comment

Whay about life coaching services? I would like to see a discussion about whether everyone benefits from life coaching. Maybe the late Sydney professor Anthony M. Grant published something about it.

Report comment

The notion that professional “psychotherapy” is “the best thing” is a load of biased BULLSHIT.

“Is Psychotherapy Overrated?”, by Kelly Tatera from thescienceexplorer.com

“Exploring the Value of Peer Support for Mental Health”, Nicola Davies, PhD, from psychiatryadvisor.com

Report comment

In reviewing the various comments posted to the article on the effectiveness of therapy, it is very clear that there is a wide range of opinions and perceptions of therapy and whether it is of any value. A number of concerns and criticisms of therapy are ones that I, in part, share. For example, given the prevalence and power of the hegemonic neoliberal ideology, it is valid to raise concerns about the commodification of therapy such that it is more a financial transaction rather than a means of providing a service to individuals in need. There is ample evidence that the profit motive has assumed a disproportionate emphasis in the provision of services, who can receive them, who can deliver them, whether they are affordable and accessible, etc. Likewise, the neoliberal focus on individuals being consumers or exploited in order to extract profit from their labor does in certain circumstances lead to certain goals for therapy that do not have their needs and interests foremost. That being said, the mere charging of a fee of therapy does not make it inherently corrupt, or worthless. There are any number of other “services” for which individuals pay with the understanding that it is completely legitimate to compensate the provider. As I stated in my earlier comment, I believe that one of the primary causes of suffering of individuals in therapy is the adverse impact of oppression, inequality, and other forms of social injustice (see my blog in MIA, “The Hidden Injuries of Oppression”). These forms of suffering can be usefully and meaningfully examined and alleviated in therapy as has been described in literature from Critical Psychology, radical psychology, and similar socially responsible schools of thought.

It has been the observation of a large range of theoretical perspectives (and has also been my experience) that the most common reason for people seeking therapy is something described in the quote by Alan Watts in my earlier post. That is, a powerful experience—generally a loss—that turns their life upside down, challenges their worldview and the sense of order and meaning it provides, and confronts them with significant existential issues. These include one’s mortality, the loss of control, a sense of isolation, and the inescapable uncertainty that is part of life. Jerome and Julia Frank describe this as individuals who feel demoralized, disheartened, disillusioned, and confused. The loss of one’s assumed view of the world is equated with a loss of one’s very sense of self. This leads to a disturbing sense of alienation or disconnection from oneself, others, the world, and some higher power or order of meaning.

The etymological root of “therapy” is “to attend, do service, and take care of”. All of these get to the heart of genuine therapy. This meaning also becomes clearer when we realize that the earliest healers were shamans or other indigenous healers. Essential truths from these traditions continue to be relevant to therapy who sought to restore one’s relationship to self, others, the natural world, and a higher power. Therapy is not simply talking about problems or feelings, telling people what to do, or “fixing”. There are many aspects of life that cannot be fixed, such as the Buddha’s and existential theorists’ observation that there is suffering in life that is inevitable and so cannot be removed. As social beings, humans are deeply shaped and impacted by their relationships. Those relationships are jeopardized or lost following the loss of one’s worldview. Thus, it is by means of an intense and powerful relationship with someone who attends, serves and cares for the sufferer that the process of restoring a sense of connection and meaning can be achieved. It is the “experience” of being in such a relationship and in the presence of another person who suspends judgment about what they are going through and who—as much as possible—selflessly is open and present to their suffering that promotes. The core value of a healer is compassion—literally, to suffer with. This is both taxing and demanding for one doing therapy. But his or her ability to travel with persons through their despair and to hold out the possibility of emerging out of the other end with a new meaning and purpose despite their loss is the core of therapy. I recall working with a person who had suffered a significant stroke and, just as he was improving from its impact, learned that he had been diagnosed with a significant form of cancer. Or another individual who, due to suffering from a significant case of diabetes, had lost her vision and kidney function and then required an amputation of one of her legs. There was nothing I could do to alter these horrible circumstances. There were no words I could offer that would somehow soften their sense of anger, fear, and despair. But the one thing I could always give them was myself as totally as possible, to be open to their suffering, and to extend sincere care and concern for them. That was the only path to genuine healing.

Report comment

“The etymological root of “therapy” is “to attend, do service, and take care of”. All these get to the heart of genuine therapy.”

First of all, there’s no magic in “therapy”. And second, caring for one another emotionally and psychologically is what makes humans human. And third, charging money for doing so is an act of oppression in and of itself.

The truth is “therapy” harms a lot of people, but that’s something that’s rarely heard because of all its rhetoric.

Report comment

Equating charging money for doing therapy which generally individuals have the choice of doing or not (in other words, they are neither coerced nor threatened with violence to pay for therapy) with genuine instances of what constitutes oppression not only demonstrates a lack of understanding of what oppression is, but also serves to minimize or trivialize true instances of oppression. Such true instances of oppression are enslaving people of color, colonialism,patriarchy, the genocide of indigenous peoples, and the multiple negative effects of poverty, particularly when paired with immorally justifiable economic and wealth inequality.

Report comment

Frank, while I agree that paying for a quality therapist (if one is fortunate enough to find one) is hardly a form of oppression, I have to say that I’ve seen PLENTY of garden variety straight-up intentional oppression of psychiatric “patients” in the name of “helping” them that most definitely would meet any definition of oppression you can come up with. Dishonesty, use of force, holding people against their will without cause, forcing “treatment” that causes brain damage and early death while claiming that all of these issues are the patients’ problem and were not caused by the “treatment. All of these things are offensive to any sense of justice, freedom, equality of rights and basic respect due to any human being. It seems to me you are singling out the relatively rare case of a free and relatively well off adult engaging in a more or less fair exchange of money for services, and assuming the purchaser has both the information and the wherewithal to resist efforts to indoctrinate or mistreat them at the hands of the therapist. That’s a lot of assuming!

If you slow down a minute and read some of the experiences shared here on MIA, you will see that the vast majority of commenters do not have the kind of experience you are describing. Many are forced against their will to do things they object to with neither information nor consent. Many more are lied to and emotionally manipulated into accepting a very unhealthy framing of their situation and into accepting “treatments” whose benefits are overblown and whose dangerous consequences are minimized or denied completely. This is the oppressive situation we’re dealing with. And it CAN happen in a paid therapy relationship, too.

I’m sure you are a caring person who probably does a good job helping your clients. What I don’t think you get is that you are an outlier in the world most of the posters live in. It’s very understandable that most are extremely skeptical of therapy in any form. It’s been used to hurt them!

Report comment

I think not having enough money to pay for something you need to survive emotionally qualifies as oppressive, which in this context happens to be emotional support. And imo, having to pay for emotional support says a lot of bad things about the world we live in, especially since so many people barely have enough money to feed, clothe and house themselves adequately, much less pay for “therapy”.

“The proverb warns that ‘You should not bite the hand that feeds you’. But maybe you should, if it prevents you from feeding yourself.” – Thomas Szasz

Report comment

The medicalization of psychology and the monetization of confidential relationships, (i.e., “psychotherapy”), are the manifestation of a society built on oppression: Exploitation, Marginalization, Culture of Silence (powerlessness), Cultural Imperialism, and Violence.

“FIVE FACES OF OPPRESSION”, @projects.iq.harvard.edu

Report comment

The many faces of oppression constitute the “mental health” system: its above-average psychiatric incarceration of people of color, its colonial roots, its patriarchal beliefs and attitudes, and its historical genocide of indigenous peoples.

And what the heck is “immorally justifiable”?

Report comment

” …the one thing I could always give them was myself as totally as possible, to be open to their suffering, and to extend sincere care and concern for them. That was the only path to genuine healing.”

No one need be a therapist to support others in times of need. And there are many paths to genuine healing.

Report comment

The idea that psychic salvation is best realized by spilling one’s guts to paid strangers is a sad commentary on humanity’s spiritual evolution, as the increasing reliance on plastic relationships (i.e., “psychotherapy”) too often makes people forget how to be their own and other’s keeper, in ways big and small.

“Owe no one anything, except to love each other, for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.” Romans 13:8

“We Are Each Other’s Keepers”, by Devon Corneal, from huffpost.com

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment

“Our journey is about being more deeply involved in life and yet less attached to it.” – Ram Dass, from “The Freedom of Being Nobody”, courtesy After Skool

Report comment

I wonder where one gets therapy due to the years of therapy they’ve gotten.

Report comment

[Removed at request of poster]

Report comment

My recovery from “therapy” got started when I began listening to my gut which kept saying that “talk therapy” wasn’t for me. And finding these videos were a huge help: “A Former Therapist’s Critique of Psychotherapy: Daniel Mackler Speaks”, and my favorite, “Is My Therapist Good or Not?”, also by Daniel Mackler. Both offer the validation I needed to do what I felt was best, which was to give “therapy” a final heave-ho, a decision I’ve never regretted. And come to think of it, isn’t that what “therapy” is all about?

Report comment

Removed now

Report comment

Given the context of discussing the monetary aspect of therapy and its direct impact, I would like to provide a more comprehensive response. Firstly, it is important to note that most individuals seek therapy not for existential or philosophical reasons, but rather due to burnout, stress, anxiety, depression, oppression, or other diagnosed conditions. Sometimes, individuals become so intertwined with their diagnosis (which is coercion and political just read more MIA) that it becomes difficult to distinguish their identity from the condition itself.

Secondly, the pursuit of meaning in life is not solely the responsibility of therapy; it is a fundamental aspect of human existence. Each person’s search for meaning is as unique as their physical features, with no two individuals sharing the exact same perspective. So not sure how anyone ever found meaning in therapy. It is crucial to recognize that therapy only occupies a small portion of an individual’s daily life, typically in the form of weekly sessions or less. Understanding this context is important because the therapist’s role is to exert influence primarily through language (and non-verbal) during the limited duration of the session. Although this influence may not have tangible or material manifestations like those of a medical doctor or a massage therapist, it involves engaging with the individual’s internalized thoughts and experiences. There is more but I will stop here.

Nonetheless, my main points can be summarized as follows: psychotherapy is symbolic and narrative-based work, distinct from the physical and material nature of medical or other physical therapy. Trauma is physical and influence and needs a radical reality based of equity for recovering because trauma happens when equity is oppressed.

However, this distinction may not always be apparent to the clients. In some cases, when clients inquire about making the therapeutic process more tangible and comprehensible and equitable, they may be met with additional diagnoses as a response to their “resistance”. The question then arises: resistance to what? The answer lies in resisting external influences. Oppression is an external influence! A therapist is keen on changing the person inside when trauma often comes from outside! Extreme incongruence! People want a witness because during trauma, most people close their eyes and bodies and cannot recall so they need safe space to vomit but even this is called trauma dump and noooo you must hold in!!! what????

The therapist needs to cry and be political to say the system sucks! Figuratively speaking not focus on the inside of the person’s physic to dissociate them from reality so they collapse internally again!

In therapy, giving consent does not imply that one must unquestioningly accept the therapist’s influence. The coercion of influence, which involves eradicating resistance during therapy, is the underlying issue. The person could not “resist” trauma, and now the therapy process requires unconscious compliance and obedience which is exactly the methods that created the environment of trauma in the first place.

It is essential for adults to maintain their autonomy and “resist” undue influence from ethically trained, safely oriented therapist. The therapy process should be the only place in the world where one can resist and be conscious how they resist so they can resist the oppression outside. A modeling of how to become conscious of the oppression and how one (all of us healthy or not) resist the barrage of abuse we experience in having society!

Unlike children, adults possess discernment, and acknowledging this is a significant challenge. When two adults are in a therapeutic setting and one is labeled as “sick” or inferior in knowledge (even though we understand this to be inaccurate), such labeling can be disabling and a deficit itself and to climb out is almost impossible! So we break people in therapy, so they can put up with the reality of oppression!

The therapist should be ready to breakdown and understand the person in the room. All therapists need their own groups and safe place to continue dumping the trauma….and this is the social bonding. We all carry each other and take farther and farther!

But in reality, we do not actually allow trauma dumping in therapy – the therapy process has the boundary of steel! It is the ultimate double-bind!

Only after we dump the trauma, then we feel equal. And that is what people are looking for equality not one must submit to dependency….we are all dependent. I pay the therapist, and I gained space. And therapist takes my money and finds another place to dump their trauma and mine….human chain of empathy! But our therapists are not in it for the job…just for the money. Sorry!

Report comment

“The therapy process should be the only place in the world where one can resist and be conscious of how they resist so they can resist the oppression outside.”

Why should “therapy” be the only place to do that?

Believing that “therapy” is more than it is is how it gets away with charging people money.

Report comment

It is not necessary for it to be, @Birdsong; however, unfortunately, we also reside in a society that requires an environment for addressing power structures with minimal adverse effects. Some individuals may attempt to find solace in religion, institutions, or other cultural enclaves like work (a modern person’s prison), but ultimately, there must be a space for mature individuals to learn detachment and engage society after re-evaluation fully and consciously perhaps to impact change.

Of course, the fundamental question arises: why is there a need for such a space in the first place? And why can’t everyone be free to exist and collaborate harmoniously? The answer is quite straightforward: capitalism (which values competition over cooperation), patriarchy (which elevates the representation of males above 50% of the population), inequality and oppression (evidencing our failure to learn from history), and the list goes on…

Report comment

Yes, but…the point I keep trying to make is that “therapy” itself is a patriarchal concept based on fictional diagnoses, an asinine power imbalance and fees which make it capitalism’s crowning glory. So, it seems contradictory to prance off to “therapy”, check in hand, to, as you say, “learn detachment and engage society after re-evaluation, fully and consciously perhaps to impact change” when all one is actually doing is engaging in and supporting a harmful status quo. In fact, I think the things you mention are far better accomplished by staying home and reading MIA.

Report comment

@Dogworld. I enjoy your analysis, which I find much more thoughtful than the professionals in MIA.

Yes, the insistence of therapy’s philosophical underpinnings puzzled me too. I’d be utterly vexed if I entered therapy to resolve my mundane little problems: i.e. underdog at work and friendship, dateless, mousy, and was the receiving end of a grand lecture how well-read my therapist was in philosophy. Every therapist I’ve seen has a one-size-fits-all shtick, but telling my then young adult self that my real issue was in fact an existential crisis…I’m just thankful I was just bullied in the manner I was rather than by this pedantic nonsense. I certainly didn’t go to therapy to confirm the therapist’s academic brilliance.

Oppression: my oppression was subtle, and I colluded in it, unfortunately, for I handed my oppressor the weaponry of my sorrows, vulnerability and credulousness. I bought my therapists’ snake oil, that they could do what no human being could, guide me to change my basic uncomfortable personality. But boy, did I hang on to that myth, maybe because my therapists believed it themselves. And in process I subordinated myself to them, idolized them, and gave an increasing amount of myself away. Therapists used my life’s sorrows to lead me down the garden path.

I fear that therapists get so entangled in their theory that they lose what happens between two people on a basic, non-theoretical level, looking at themselves at the Queen Bee or Bully/Tyrant in high school, who, through dominance signaling and social aspiration, demands everyone else’s toadying.

Even with this gray hair, I don’t spend time in existential crisis. Maybe because I find the big questions about purpose rather amusing.

https://disequilibrium1.wordpress.com/

Report comment

Here’s a few more words about therapy straight from the horse’s mouth:

“I think actually, the irony is that so much of psychotherapy is made into this mysterious world of ‘wow, the therapists and what they do is such brilliant stuff and there’s so much insight involved’. Well, actually I think a lot of people can do exactly what psychotherapists do, and do it much, much better if they just have a gift of having a comfortable, caring, respectful conversation with another person, and lots of people can do this.”, from the video “Why I Quit Being a Therapist – – Six Reasons” by Daniel Mackler, @ 8:06

Report comment

Much of mainstream psychotherapy is a walk down a blind alley for the “client”: “Psychotherapists Who Are Less Healthy Than Their Clients”, a revealing YouTube video by Daniel Macker.

Report comment

Should everyone be in therapy? A better question: What is “therapy”?

“Do Some People Need Therapy? — Analysis by a Former Therapist”, a video by Daniel Mackler

Report comment

Comments on these therapy-critical articles have a pattern. Respondents use the topic to explore their injuries. Then an angry therapist appears, posing as The Voice of Authority, in angry rebuttal, rebuking, quashing, nitpicking and sidetracking, heedless of the clients’ pain.

What goes wrong in a therapy room? Look at these threads. Based on my anecdotal experience, I’d suspect therapists are an incurious, overweening group.

This points to the fundamental flaw I suspect in the whole therapy paradigm. Every therapist I’ve encountered skewed toward dominance, with a desperate neediness to be idolized as the infallible expert. I entered therapy as a client seeking a strong man, a shaman who holds Life’s Answers, and therapists were more than happy to oblige with their distorted performance art.

Authoritarians and supplicants go about life in antipodal skins. They’re unlikely to understand each other, nor can the authoritarian begin to understand the problems of a habitually subservient personality.

Report comment