To illustrate how I’ve come, in part, to perceive and understand traumatic chemical brain injury, or TCBI, caused by psychiatric drugs (though other classes of medications cause akathisia and other harm), here’s an analogy I find useful.

Imagine traveling in a large van filled with people on a mountain highway at night. Due to the many bends and turns on the road, it’s difficult to see oncoming traffic. As you emerge from a sharp turn with a blind curve, you don’t even see the jackknifed semi-truck sliding straight toward your van before the collision.

Some passengers may not survive the crash while others might walk away with mild injuries. There might even be one lucky passenger who walks away without a scratch. However, based on the speed and mass of the two vehicles, the more likely scenario would be that all passengers will be injured to varying degrees and in myriad ways, from severe to moderate to mild. Some injuries will be life-threatening or disabling. Other injuries might be late-appearing, and still others will create secondary complications that could become chronic.

While you and the other passengers shared the same van that was hit by the same truck at the same time and on the same road, it would be unlikely that all the passengers in the van would sustain the exact same injuries. On the other hand, there might be similarities across the board.

When someone sustains a TCBI from psychotropic drugs, there are certain markers that remain consistent. Just like soft-tissue damage in the neck (whiplash) is a common injury after a car accident, for many people suffering from drug harm, akathisia, easily the most distressing and unbearable, is common and can persist long after drugs are discontinued.

That said, no matter how similar our stories or experiences may seem, we are sitting in different parts of the van, and most importantly, we are different people. Yet, we all have something in common: we survived the crash, and we are injured.

In my last piece, “Recovery from Akathisia: Historical Perspective for Healing,” I detailed drug harm that unfolded over the course of more than 25 years to clarify the extent of the damage, and the severity of my injuries. The damage was debilitating, and recovery seemed unlikely because as time wore on, new and even more incapacitating symptoms kept developing, symptoms seemingly unrelated to one another, so neither I nor my doctors could account for them. But in our relentless search for answers, my husband and I started to see patterns emerge, reiterations of the same ideas that led me to understand the many different ways psychotropic drugs had impacted my brain function, causing injury and damage, including a disabling condition called ME/CFS.

Most people aren’t familiar with ME/CFS, but that’s okay. Learning about ME/CFS was, oddly, how I came to understand the experience of akathisia. Understanding akathisia was an important step in learning ways to manage it.

What Happens in Vagus…

If you are anything like me, the mere suggestion that my conditions and symptoms were under my control or “all in my head” would be met with indignation, incredulity, and anger. No, we cannot “think” ourselves well. These are powerful neurological processes that have been changed, injured, or damaged by chemicals. These are not conscious, and they are largely out of our immediate or direct control: neuro-processes that are billions of years old and run on autopilot with or without our help.

But how we perceive things can and does inform neurological processes.

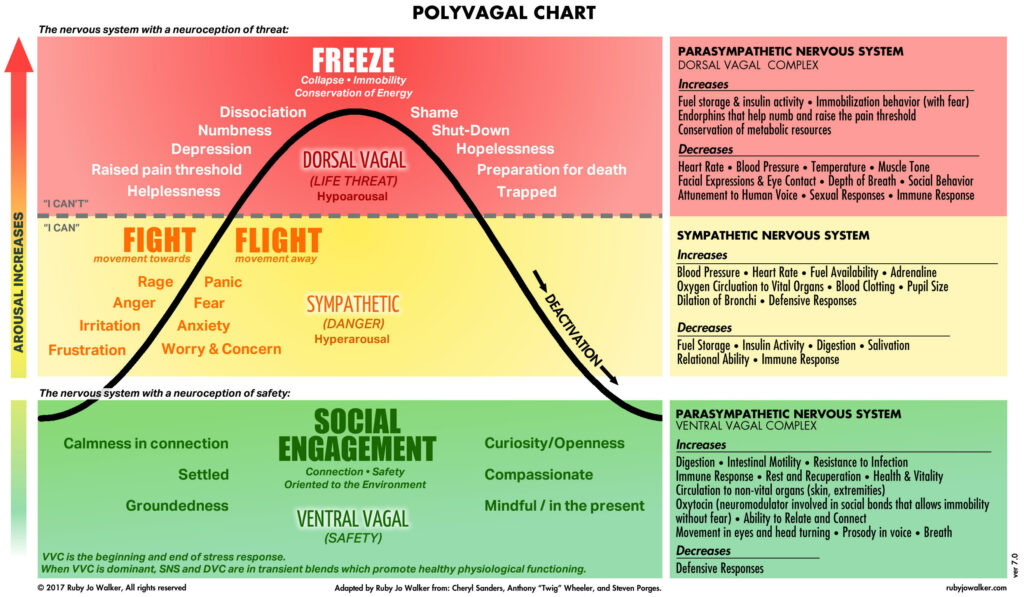

I learned a lot about the functions of the brain and nervous system from the TBI specialist I went to see in 2019. Technically, he is a functional traumatic brain injury specialist. He emailed me the chart below and it validated much of what I was beginning to understand about the brain, the biological processes of akathisia and other drug harm, and my overall health. Polyvagal Theory is still technically a theory, and I didn’t do a deep-dive into it because the chart itself was what captured my attention (click it for a closer view).

When I saw the polyvagal chart for the first time, the shift in how I viewed drug harm was profound, validating, and empowering.

When I saw the polyvagal chart for the first time, the shift in how I viewed drug harm was profound, validating, and empowering.

If you don’t know, the vagus nerve is under the purview of the autonomic nervous system, or ANS, which is in charge of most of our unconscious body processes. The vagus nerve is a main component of the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) which works to modulate sympathetic nervous system (SNS) arousal, commonly known as the “fight or flight” response. The PSNS regulates heart rate, breathing, immune system, digestion, lubrication (remember “dry eyes”?), and calms SNS arousal. The term “rest and digest” refers to PSNS function. If you experience dry eyes and mouth, that is the PSNS not functioning well.

As I read the psychological states on the left, and their corresponding physiological symptoms to the right, something clicked.

If you’ve experienced akathisia, or know someone who has, please review the states found on the left in the yellow portion under “Fight” and “Flight” and see if they seem familiar. From my experience, these are all descriptors of akathisia—from its mildest to its most acute expressions. Notice how the psychological states in red also correspond to akathisia in some of its more extreme and dangerous forms. For me, I felt a type of terror that froze me in place. This is the body’s reaction to a life threat, except when there is no life threat, it is an expression of nervous system injury and dysfunction.

Take a moment to review the diametrically opposing physiological processes in the red and yellow areas on the right. If the areas in yellow correspond to nervous system hyperarousal, then it struck me that the areas in red could describe, among other things, the “cell-crushing fatigue” of ME/CFS. ME/CFS is not an autoimmune disorder and it is not a discrete condition. It is neurological dysfunction, a response to chemical nervous system disruption that has become maladaptive. And based on my history with psychoactive chemicals mucking up my brain and nervous system function, how could it be anything else?

In reviewing the yellow and red areas on the far right of the chart, how many of these physical dysfunctions directly correspond to the known effects of psychiatric drugs? I won’t keep you in suspense—all of them do.

I began to ask myself what would happen if these brain-body-mind systems were ramped up in someone for too long. How would being in a state of dysfunction impact or change brain, endocrine, and other systemic functions? Could these changes lead to damage in these areas? And if so, isn’t it reasonable to define that damage, caused by psychotropic drugs, as chemical brain injury?

The answer, I’m afraid, must be yes.

By Any Other Name

I have heard people refer to akathisia in numerous ways. I used to call it “The Pain,” among other “flowery” descriptors, and that makes sense. When human beings don’t understand something, especially when it’s frightening and powerful, it’s an evolutionary and biological impulse to mythologize it and create narratives that reinforce it. I know this because I did it. But I had to stop giving akathisia more power than it deserved, and that began by reconceiving it as traumatic chemical brain injury.

I stopped using possessives with it (“my” akathisia) and I stopped giving it proper names. I stopped conferring mystical powers onto it that made me believe it could swallow me whole.

This realization had to happen for me to begin my recovery. I stopped thinking of akathisia in terms of the disease model and instead began thinking of it as an injury. Akathisia is not the car crash; it is a result of the car crash.

The following attempts to establish some foundational principles about brain and nervous system function. This was a defining component in changing how I perceived akathisia. Why is it important to change how we perceive it? Because perception is what creates, or changes, our subjective experience of literally everything.

This is Your Brain (on Drugs)

To fully understand how I got here, to a place where I no longer experience daily akathisia, it’s important to understand how and why I came to reconceive my physical and psychological decline as a result of chemical brain injury from psychotropic drugs. My definitions are jargon-free and simplified because I’m not a brain scientist. However, I don’t need to be (and neither do you) to have a basic understanding of the brain’s overarching role, so this is a good jumping-off point.

While the functions of the brain are numerous, if we boil them down into the most basic functions, it’s easy to see how all its other duties fall under these main roles. The brain’s first, most basic function, is to keep you alive. Its second function is to protect you and keep you safe. Its third job is to maintain homeostasis (which could fall under the purview of “safe,” but there’s enough variation to warrant listing it separately). The final basic job of our brains is to solve incongruities—problems or glitches in our perceptions of reality that threaten homeostasis. From beliefs to trauma to trying to figure out a seemingly no-win situation at work, your brain is constantly seeking ways to iron out the wrinkles of your existence through a multitude of processes, for example, patternicity.

Let’s suppose that every time you visit your mother-in-law, you notice you develop indigestion the same evening. Your brain finds the pattern that best suits what you believe, and so you may automatically attribute the GI upset to the visit, conveniently ignoring the greasy fast food you routinely pick up and eat in the car on the way home from her house. As stated earlier, we are often mistaken when it comes to causality. Another way our brains create harmony for us is through confirmation bias, which is the tendency to subconsciously seek evidence to support what we already believe.

In other words, there are a multitude of ways our brains have learned to reconcile our inner worlds with the outer world.

With that simple overview of the brain’s job, let’s now consider its complexity. The human brain has been called the most complex system in the universe. It is your “supercomputer,” only it’s even more elegant than that. Without your brain, you would not taste, see, hear, experience, feel, dream, think, remember, walk, breathe… well, you would not be. If you stub your toe, your brain feels the pain. You don’t see with your eyes; you see with your brain, and so on. And while philosophers have spent thousands of years trying to define the concept of Mind, there is one point upon which they all (unless they’re dualists) concur: the mind cannot exist without the physical brain. The more I learn about the brain and its functions, the more humbling it is. I am in awe of it. Based on all that we as a species do not know about the brain, the cavalier attitude of medical providers when prescribing psychoactive chemicals is alarming.

Now, let’s consider the job of psychiatric drugs. While this, too, is reductive, it’s much more accurate and complete than the description of the brain’s responsibilities, because the scientific evidence, data, and most importantly, the drug manufacturers do not dispute it. The job of psychiatric drugs is to disrupt normal brain function—functions, remember, that are part of the most complex system in the universe, not yet understood even by their owners or the sciences they’ve created in their attempts to understand them.

In other words, psychiatric drugs are used specifically to create dysfunction within the body’s supercomputer, an unfathomably complex system that took billions of years of trial, error, and development to evolve into its current state.

Take a moment and let that sink in.

Traumatic, Chemical

Knowing what we know of the brain, then, imagine all that can go wrong when normal function is disrupted by a hard knock to the skull. Where the damage occurs, the severity of the injury, age, general health, comorbidities, and psychosocial factors all determine treatment. “Too many known and unknown variables,” remember? But when dealing with injuries from ingested chemicals that target our supercomputers and dysregulate normal brain function, that’s a whole new level of complexity. Like sand in the gears of an elaborately built clock, certain processes slow down while others speed up, creating system-wide dysfunctions.

Usually, when someone is damaged this way, the undoing is consistent and occurs over long periods of time while, tragically, under their doctor’s care. If and when patients realize that the side effects obliterate any perceived drug benefits, the medical system is ill-equipped to help them discontinue the drug(s), let alone help them recover from injury. Often, patients are further traumatized as the harm is compounded by its misattribution to whatever underlying mental-health issue they sought help for initially, especially if more damaging drugs are prescribed.

I was fortunate to (finally) find medical providers who seem to care deeply about my well-being and who continue to be supportive as I withdraw and recover (that, or I’m such a huge pain in the tuchus, they can’t get rid of me fast enough). But it took time to re-establish trust.

I use the term traumatic chemical brain injury—TCBI—because, like other brain injuries, developing recovery strategies is based on a myriad of considerations. The injury is chemical because its pathogenesis was psychoactive drugs. The traumatic piece of it comes from being dismissed by the medical community while its providers hide like cowards behind their DSMs and diagnostic power.

So, if two of the brain’s basic functions include keeping us safe and maintaining homeostasis, imagine what our brains must do to reestablish homeostasis when psychotropic drugs, designed to create brain and nervous system dysfunction, are introduced, taken for long periods of time, and then discontinued.

Understanding to Heal

Just eighteen months ago, I was crippled by daily akathisia and other tardive drug effects. Today, I am more functional, even though I’m still mired in the process—I am currently tapering off two psychotropic drugs, including a benzodiazepine. And while some days and times are more difficult than others, I remain hopeful and confident in my recovery efforts.

But I didn’t just wake up one day feeling better. While time is essential in healing any injury, serious chemical injuries to the brain and nervous system often take more than time, rest, or a pill.

In my piece, “Akathisia: Historical Perspective for Healing,” I mentioned that by 2009, after five years of neuroleptics (atypical antipsychotics), my blood pressure and cholesterol were too high, and so was my blood sugar (prediabetes). This is known as “metabolic syndrome” and it is one of the most common features of long-term neuroleptic use. The weight gain was indicative of the chemical changes being forced on my body, but they didn’t exist in a vacuum because systems thinking shows us that our brain-and-body systems are interdependent, working together to create and maintain homeostasis.

The problem with dysfunction is that when these systems are malfunctioning, they don’t crash in logical or reasonable ways, and they go offline differently for everyone. I know many people who have sustained TCBIs who are rail thin. Others, like me, gained considerable weight. While some people are prone to infections, others become ill with autoimmune conditions, and so on.

If we take a moment to review both the yellow and red portions of the Polyvagal chart, one thing becomes crystal clear: these are some of the most basic and important automated systems in the body, and the drugs I was prescribed created large-scale dysfunction in these systems, which are under the purview of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), so their functions are automatic. Trying to reason with them is impossible because these automated systems are non-verbal, they do not speak human. It’s why simply telling yourself not to be afraid or to “calm down” doesn’t work.

Most revealing were the sections in green. I had been so ill for so long that I’d forgotten how a healthy body-brain-mind felt. I realized that the medicalized model of care had robbed me of the belief that I could heal in the same way it had robbed me of the belief that I could manage my life without drugs so long ago. While I might occasionally (and temporarily) need medical or other external support as I continue to taper and recover, understanding the role the nervous system plays in my overall health and well-being opened my eyes to the reality that I no longer had to capitulate to the medical model’s limited imagination and dismal prognoses.

That said, if our systems, our supercomputers, are “offline” because of psychotropic drugs, based on its complexity and all we do not know about the human brain, it’s important to be especially cautious when considering the addition of more psychotropics.

It should also go without saying that if you suffer from akathisia and you’re currently taking a drug (or drugs) that cause akathisia, it might be time to reassess (with your medical provider) how to proceed.

Because the damage from drug harm was so widespread for me, I had to consult several different kinds of medical providers to address whether I needed additional support to help my brain and body heal. Finding supportive medical professionals has been vital. In his upcoming article my husband, Kent, will be addressing some of the more effective approaches we’ve found when seeking support from the medical community.

Again, there are no clear-cut or simple ways to heal TBIs, especially chemical ones; they are as individual and unique as their owners. So, while my journey might resemble someone else’s, that doesn’t mean our injuries are just alike or that our recovery strategies will exactly align. But we share common physiologies that respond in similar ways to injury.

According to Headway, a brain injury organization in the UK, any injury to the brain can have behavioral and emotional consequences. It isn’t difficult to conclude that chemical brain trauma is no exception, especially when the chemicals were/are psychoactive. But, like any form of rehab after a physiological trauma, we must engage our whole selves in the process if we are to recover. Take, for example, physical therapy. The mindful and repetitive movement of our physical bodies is all about reconnecting the body and brain. But if we are to succeed, we need our minds to broker the connection.

I believe, as Albert Camus stated, that there lies within each of us an “invincible summer.” This isn’t just a banal platitude brought on by fuzzy hindsight. Hope and the belief that one can heal are essential ingredients in recovering from any form of trauma because, like most everything we do, there are neurological consequences either way. Perceptions matter.

Learning to recognize that my astonishingly complex system was designed to function well when properly supported (rather than thwarted by ingested chemicals) was a shift that continues to give me hope. People don’t heal from “diseases” or “disorders,” but they can and do recover from injuries. To what degree varies from person to person.

I’ve been in this process for seven years. And though I’m still not fully recovered, a vital part of getting to where I am now was reconceiving and resetting my view of akathisia and other drug harm as consequences of TCBI. These injuries affect some of my most important, ancient, and automated systems. In my next piece, I’m going to address ways in which we can “communicate” with and effect change in these automated systems.

I know, intimately, that we often feel as if we have no choices when we’re suffering, but we always have choices, even if they seem limited and inconsequential, so say it with me: akathisia is a brain and nervous system injury, no more, no less.

Stay tuned.

Solid article.

Based on my experience, reframing my damages with careful language had a gradual, ultimately, enormous and positive effect…it jolted me off the doomed, despairing, irrepairable hamster wheel (freaking draining) to problem solving and pursuit of ‘getting to know’ my brain as a separate but integrated part of my whole..& respect the sh%t out of it. I love my brain so much, closer to worship.

Opening myself to what IT had to say about what had happened to us-& still dealing with the aftermath-was startling. A different view, edited, cool & composed, but not without a current of ‘feeling’….it was remarkable & became the driver’s seat I needed to adjust to.

The author states…”Because the damage from drug harm was so widespread for me, I had to consult several different kinds of medical providers to address whether I needed additional support to help my brain and body heal.”…

I pursued brain testing, insight & desperately needed ‘support’ from providers within my insurance but was unable to pierce the thin, white line of shying away from challenging, critiquing, even mildly questioning the ‘results’ (damages) of another medical entity, prescriber, or specialist. They’d walk right up to the edge but wouldn’t step over the ‘line’-even presented with med records, labs, history, & research reprints…..AND a written, revoked (LIFETIME) diagnosis…that was necessary to simply ACKNOWLEDGE the cause of this train-wreck-my brain & body. Neurologists to Barrow Institute did the garden variety-what’s this? testing, shrugged, and wished me well.

The nervous vibe was palpable…most regarded my appointments as evidence-gathering expeditions-hostile to their industry-regardless of my goal-stated clearly when entering-to restore function & identify a path to optimum health. Nobody wanted to be called as an expert witness. Paranoia over liability and lawsuits from their own….that simply wasn’t there.

This wasn’t a ‘Vengeance Tour’…I was too weak, sick, & frightened (for my future). I asked for help…as they metaphorically backed out of the room.

Apparently, all ‘too much’ for them.

If the damages had been from street drugs, I would have suffocated under the barrage of ‘support’ and ‘knowledge’ regarding ‘recovery’.

I moved on quickly to my brain’s own program. It was going to be just ‘us’…as our self-rescue had been.

We good.

Report comment

Krista, thank you for reading. What you gleaned from the article was exactly what I’d hoped to accomplish with it. It can be a tough topic, not just based on how people are injured, but because of how the medical system reacts to iatrogenic harm. Your experience sounds familiar, and even today there are large elephants in the room I have to ignore to get through my medical appointments.

I’m sorry that the medical providers you consulted weren’t as helpful as they could and should have been. My husband, Kent, just completed an article that’s going to be published here in August about some of the more effective ways we’ve found in getting help from the medical community.

Our society identifies with what we do as part of who we are. When livelihoods are threatened, even peripherally, implicit bias kicks in because in the back of their minds, or deep in the darkness of them, they’re thinking, “It could be me next.” It isn’t right or fair because we’ve been taught to believe that medical providers put patient care and safety first. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. I appreciate your comments and hope you continue to move forward as you reclaim your life. Take good care. – JA

Report comment

Krista, I agree with you, doesn’t matter where you go no-one but us are ready to help. I am helping my son who is not yet wise enough to slowly taper. At 28 he knows the damage being done by the drugs, but no one wants to admit that and then help. So hell skip a day and then a pill and then starts slipping into a dark hole.

We will keep supporting each other, unfortunately we only comes to these places when damage has been done. Many are being prescribed and trust their prescribers, nothing will change as there’s too much money to be made. We must soldier on.

Report comment

Thank you. This series has been enormously helpful.

Report comment

Living, thank you for reading. I appreciate your words of encouragement–definitely helpful as I continue to write about my (limited) experiences in the hopes that others will find their way out of the dark. Take care – JA

Report comment

What helped me most, both in the management of the manic depression as well as the damage from the drugs, was to treat the mind and body as a single damaged immune system. Focusing on a diet that restores homeostasis has become a lifestyle both personally and professionally.

I am somewhat fortunate in that many of my worst symptoms are associated with the higher dopamine levels of hypomania so in a way the discomfort can be almost pleasant at times.

Report comment

Living, as always, thanks for reading and your comments. – JA

Report comment

J.A., Tone deafness was eyeball-deep with providers who had initially been markedly sympathetic to what had happened to me….looking down, shaking their heads, tsk-ing. It looked promising until the seizures started…and I was immediately greeted with ‘You should talk to someone’…a therapist.

I accepted that PNES was in the convo, but I also had an exclusive symptom of a subcortical, focal brain lesion (micrography-only caused by antipsychotic ‘exposure’ OR Parkinsons-J.Hopkins/Mayo) I (famously) didn’t have Parkinsons. Still don’t.

But terror & neurotoxins (every single m.f.-ing day for 11 years) changes cellular activity.

Yeah, it’s ‘bio’.

NOT fixed by chemicals. Fixed by LACK of them…and a daily diet of gentle kindness.

MY brain wanted Tai Chi & Qi Gong. to address my “automated systems”. It re-aligned my metaphorical and real spine, major organs, oxygen delivery systems, and self-control, inside and out. Inside was harder, but achievable.

I found a cheap class. Going thru the body & breath motions of the class, I spontaneously started to quietly sob (acting as if I had allergies).

I barely made it to my car, just sitting there letting my relief wash over me.

My brain & I were overwhelmed by the classes: gentleness, oxygen to the brain, renewal & reinforcement of my exquisite control over my brain-body-….and the SAFETY I FINALLY FELT in that room every week.

My brain knew. It knew how to fix me, soothe me, love me. Alot

The notion of ‘safety’. It was astonishing.

Report comment

Thanks for all this, Krista. It sounds like you finally started trusting your body, and in turn, it responded in kind. This is why I’m reluctant to give specifics on my personal recovery journey–it isn’t about following my process, it’s about uncovering and finding your own, something I’m currently writing about. Many thanks and best of luck to you on your healing road. – JA

Report comment

Having MTHFR homozygous mutations can cause akathisia, sometimes followed by suicidal ideation and they can also worsen TBI because they cause low Folate, high homocysteine.

And the symptoms attributed to antidepressant withdrawal…hasn’t anybody noticed that they are EXACTLY the SAME as the symptoms caused by MTHFR mutations?

It makes sense, both cause the same nutrient deficiencies.

Folate Deficiency Increases Post schemic Brain Injury

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.str.0000153008.60517.ab#:~:text=In%20addition%20to%20augmenting%20the,of%20neurons%20to%20brain%20injury.&text=Folate%20deficiency%20causes%20uracil%20misincorporation,has%20implications%20for%20neuronal%20damage.

Report comment

Here’s what I’m thinking…

MTHFR mutations cause low folate, low Vit B12, which affects methylation.. Latuda causes anemia…in other words low folate and Vit B12.

Report comment

I have the MTHFR mutation. I stopped all supplements when this started feeling they could be the cause. Now when I try to take any b supplements it makes the akathisiaworse. What do I do? No hope.

Report comment

Michelle,

I’m sorry for the late answer, I just saw your message.

Not all doctors know how to treat MTHFR mutations and not everybody benefits from the same nutrients, so find someone with experience treating. Dr Walsh from the Walsh Institute has treated large numbers and he has a program that trains physicians. If you visit his website they have a list of all the doctors who have been through the training so you can check to see if there are any close to you.

Report comment

This article gave me so much hope. I’m in year 2 of TCBI (Akathisia) and I am losing hope….because I’m still slowly tapering 2 meds and have about 32 months left. I hear of people healing on “new” meds or years after off….but what about those of us injured in the middle of taper? Is there hope for us? You made me feel like there is. I’m not looking for full healing yet….I just need the Aka to

Lift a little….even just 10%!!! Just a little less terror and acid brain feeling …

Report comment

It is hard to read your work. It is hard to see someone find help when I can’t get help for the simplest of illnesses let alone this. I have no one. I have no support system. I’ve been told by “friends” to go away. I’m too much trouble. I have an elderly mom to care for and that’s it. I’ve been sick many years with other illnesses way before this. I didn’t get help then either. I won’t get help now. I’m planning. What I won’t say. I have no choice but to plan. I will soon be homeless. Imagine going through what you are living in a car. There’s many who are. I am not strong enough.

Report comment

JA,

CFS, and the GI problems, vitamin deficiencies and strange sensitivities to food and spices…all related to MTHFR mutations. Seizures too.

Report comment

Beautifully written! I love the van/semi-truck analogy, it fits perfectly. Even better knowing I got into an actual accident a couple of months ago…apparently I had some sort of seizure 8 months after stopping a benzodiazepine. Quitting the meds has been the most bizarre experience. Thank you for spreading some good information, J.A.! I’m glad you’re functional enough to write so perfectly, I’m not quite there yet hah! I do believe our brains will heal themselves, hang in there everyone.

Report comment