I’ll never forget standing beside my sister Lucy as she was strapped to a gurney during a midnight admission to an E.R. in Cambridge, Mass.—one of 13 or 14 hospitalizations, I’ve forgotten which—and hearing her try to persuade hospital workers to release her.

She was profoundly articulate and compelling as she made her case, but by then she’d been diagnosed as borderline, which, of course, meant that anything she expressed in her own defense would be discounted as manipulative and disordered.

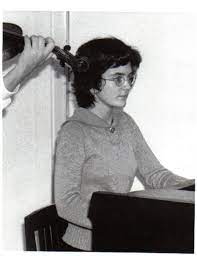

I don’t remember what I said, exactly. What I wanted to do, then and always, was scream at everyone in screaming distance: Don’t you realize?! This woman is the sweetest, most caring, most extraordinary soul you’ll ever meet in your life! She’s funny as hell! She’s a pianist! She plays Beethoven like she knew him! Treat her with compassion! Acknowledge her humanity! Listen to what she says!

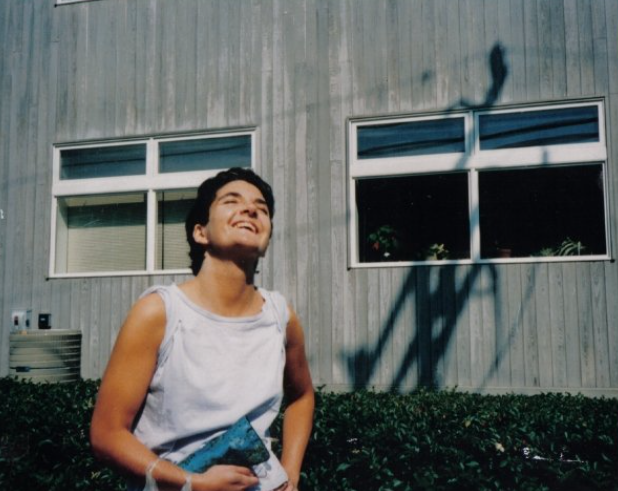

This was back in the late 1980s, shortly after I dropped everything and went to live with her. I’ll never stop dwelling on that moment and the system that failed my sister. I’ll never stop trying to process her suicide in 1992, just as I’ll never stop working to process my husband’s in 2011. This is the nature of grief following suicide: It never truly resolves. Those of us left behind spend the rest of our own lives trying to understand why our loved ones’ were cut short—and what might have helped them survive. We envision alternate timelines in which they healed, recovered, perhaps blossomed, even thrived.

Right now I’m finishing a novel in which I try to bring Lucy back from the dead. In it, I persuade an eccentric Harvard neuroscientist to put me into a coma, and I zip up to heaven on a quest to drag her home. It’s a bizarre little book, probably unpublishable. But I don’t care. It’s been a way for me to honor Lucy, visit her, see her in a new light, understand her better. It’s been a prod and a platform for questioning all that happened to her and imagining in a different reality, a different realm, one where she isn’t drugged and harmed, one where she isn’t hospitalized, one where she brings joy to herself and others through music and so much else.

As it was, she couldn’t. Near the end of her life she couldn’t concentrate. She couldn’t play the piano. She abandoned her dreams of becoming a concert soloist. She couldn’t work. She couldn’t live with hope. By the close of her ordeal she couldn’t make it through a day, or barely a moment, without wanting to kill herself.

From the beginning, she also couldn’t get the system to care about her. Once she started being hospitalized? Labeled as This, That, and The Other Thing, drugged on X, Y, and Z? Forget it. Her nutty sense of humor, her profound musicianship, her fondness for tea and chocolate, her kindness toward her goofball younger sister: None of that mattered, because she didn’t matter. Not to those who were charged with helping her. Not the way she deserved.

The long arc of Lucy’s story began at birth, when forceps squeezed her temporal lobes and caused a form of epilepsy that remained undiagnosed for decades but prompted hallucinations and other extreme states from a very young age. Later on she recalled watching the grass wiggle without a breeze. At Harvard, during her conversion to Catholicism, she saw and spoke with God. But at the time, she had no idea. I certainly didn’t, as she hadn’t told anyone about her childhood experiences. Had she, perhaps her temporal lobe epilepsy might have been identified as the cause—and perhaps her course through healthcare might have taken a different route.

Instead, she was slapped with one psychiatric label after another. BPD. Major depression. Antisocial personality disorder. Panic disorder. Histrionic disorder. Manic-depressive (now known as bipolar) disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The list goes on.

And even after they identified her TLE, she kept being diagnosed with additional disorders and kept being prescribed all sorts of drugs, including some to combat the pileup of side effects. Beyond anticonvulsants, the long paper trail over the course of her treatment included three dozen or so prescriptions. Tricyclics. SSRI’s. At least one antipsychotic. Several sedatives, including Xanax, to which she quickly became addicted. Oh, and lithium. Also Cogentin, a Parkinson’s drug. Plus Cylcert, a stimulant, which came with a risk of liver damage. You name it, she was on it at some point, and I’m only exaggerating slightly.

“You’re on so many drugs, you could die of organ failure,” one of her doctors told her. I didn’t like this guy. I didn’t see how anything he did helped my beloved sister. Instead, whenever some new drug dropped, he whipped out his pad and wrote her a script.

This or a different doctor, I can’t remember who, pushed her to have electroconvulsive therapy at McLean Hospital outside Boston—after she’d been diagnosed with TLE. There they rolled her into an oddly sunny room (or so my memory tells me) and plugged her with electrodes. I wanted to stay by her side as they zapped her brain, prompting a seizure, but I wasn’t allowed. Of course I wasn’t.

None of this made any sense to me. Not the ECT, which rocketed her to an artificial high for a couple weeks before she crashed and burned, complete with memory loss. Not the multitudinous diagnoses. Not the nonstop cascade of drugs, then more drugs, then more. Yes, I knew Lucy was suicidal. We talked about it frequently—her pain, my fears. She made one previous attempt before her final one, later writing an autobiographical account of waking from her three-day coma that I’ve been fictionalizing and incorporating into my novel.

None of this made any sense to me. Not the ECT, which rocketed her to an artificial high for a couple weeks before she crashed and burned, complete with memory loss. Not the multitudinous diagnoses. Not the nonstop cascade of drugs, then more drugs, then more. Yes, I knew Lucy was suicidal. We talked about it frequently—her pain, my fears. She made one previous attempt before her final one, later writing an autobiographical account of waking from her three-day coma that I’ve been fictionalizing and incorporating into my novel.

But I also knew that she hadn’t been actively, acutely, horrifically, continuously suicidal until after she’d started seeing a psychiatrist. Until after she started being medicated. Before that she’d been struggling, yes, but she could make music. She could live without trying to die. In retrospect, after all that I’ve learned in my years reading and working for Mad in America, I wonder about the side effects. I recall some of the agonies Lucy described to me as facets of her TLE and “mental illness”—the suicidal ideation, the manic episodes when she bolted into the night, the “depersonalization,” the sensation of ants crawling up and down her body—and I wonder, now, whether she was actually suffering from akathisia and other iatrogenic harms of the very drugs she was put on and taken off, often abruptly. Perhaps she suffered from withdrawal, too.

But we had no way of knowing, back then. While psychiatric survivors had started speaking out in the 1970s, there was no internet. There were no blackbox warnings about suicide risks, and the Hearing Voices movement was just bubbling up. There were no universally accessible resources and information on alternate approaches. Had Lucy met someone in person, some clinician or peer, who questioned the existing paradigm and offered another way, that might have changed everything. But she didn’t.

All of which prompts an inevitable and endless rash of what ifs. What if my sister hadn’t been misdiagnosed repeatedly, her temporal lobe epilepsy unrecognized until far too late? What if she hadn’t gone on a satchel of psychiatric drugs, suffering harms no one acknowledged back then? What if she’d gone on them but recognized some of her symptoms as side effects? What if she’d encountered some other form of support?

Maybe, had Lucy lived just a little longer or was born at a later time, she might have found a way. In my bonkers novel, I chew on all of this: Not just the what ifs but the mights. In one alternate timeline I envision on my jaunt to heaven, she might never have been misdiagnosed and overmedicated. She might never have been drugged and damaged. She might have been treated with utmost empathy and care. In another timeline, she might have weaned herself off all those drugs, recovered from all their harms, and learned to live with her TLE and hallucinations. Listen to them. Even grow with them.

Then she might have fallen in love, gotten married, had kids, and been a fun, wacky aunt to her sister’s brood. She might have resumed playing the piano. She might have performed Beethoven’s “Waldstein” sonata before rapt audiences who gulped down her insights, who bathed in her warmth. Visiting her in the afterlife in my book, I can hear the music coming from the old Mason & Hamlin in our childhood home. I can watch her at the keyboard, swaying, pressing, leaning into the power and poetry with a heft and insight I haven’t seen or heard in 35 years. And I can picture, as I do, some miraculous split in the space-time continuum that allows her to come back. Make music. Be with me. Be well.

I know things aren’t exactly perfect in mental healthcare, these days. I know psychiatric treatment continues to harm countless people. Looking at the critical psychiatry movement and all the personal stories being told on MIA, I know that Lucy’s saga of drugs, hospitalization, silencing, and dehumanization is still too common. Consider the abuse of people in treatment, the loved ones trying to help, the surge in antidepressant usage among youth (most recently, in Australia and New Zealand), or the grieving parents calling for more attention to the risks of suicidality (in the UK).

They speak out because they have to—because, once again, grief following suicide is a forever proposition. There’s no getting over it. There’s no making sense of it, not really. There’s only the constant urge to tell the stories of our treasured ones who tried to stick around, who tried to make a go of things, but couldn’t find any respite or recovery in the prevailing system. Not then. Not now. Not all these decades later.

Maybe they didn’t matter to that system. But they matter to us, and always will. And the system needs to change.

In some other reality, Lucy would be calling for it.

This is why the alleged medical model of psychiatry is actually a pseudo-medical model. Notice how none of these psychiatric sachems bothered doing something pedestrian like an EEG, but derived diagnoses with information gathered from the Astral Plane to order a barrage of psych drugs, apparently fired en masse.

Report comment

Psychiatry where we pretend to offer LOVE just for money is a way of practizing prostitution. This is confirmed when we read the book “METAPHYSISQUE DE LA PUTAIN” by LAURENT DE SUTTER. We also have a similar problem in politics where in principle we work for the LOVE of our HEIMAT and so many people only work to make money meaning they are only being prostitutes and exerting a way of pressure to people imposing laws that feel like injustice being the cause for terrorism in the whole wide world.

Report comment

Yes. Though to be fair, an actual sachem would have done a far better job in treating my sister with compassion and comprehension of her humanity. The people in charge of psychiatry have a lot to learn from indigenous people.

Report comment

Amy

What a profoundly personal and passionate explanation of your journey as a journalist and activist focused on the harm and crimes committed by today’s so-called “mental health” system.

AND, what a beautiful tribute to your precious sister, Lucy, who continues to live and breathe through your powerfully descriptive words that truly reveal the best of what humanity has to offer.

Today’s oppressive and corrupt institutions (and those in power who run them) are so deeply flawed and unresponsive to necessary changes, that only a Revolution of immense proportions can save the planet and allow humanity the opportunity to flourish and reach its full potential.

Carry on! Richard

Report comment

Beautifully said! Thank you Richard!

Report comment

Thank you so much for these kind and moving words, Richard. Means so much to me that you and other MIA readers now know a bit about my beloved sister. And amen, we need profound change.

Report comment

Yes, it is an intensely moving piece, beautifully written. I know so much of this I’m afraid from my own experience in England.

Report comment

I’m sorry for your loss, Amy. Thank you for this thoughtful musing on your sister’s death.

Sam

Report comment

Thank you, Sam, for reading the piece – and for your words of condolence.

Report comment

Thank you Richard for your reply to Amy’s writing and family narrative. I coukd not say it better.

Report comment

Thank you, Mary.

Report comment

I’m so sorry for your losses. I am so grateful for your compassionate insight into your sister’s life experience. It is difficult enough being a creative person in our culture that focuses on drive, competition and achievement as the norm for acceptable behavior without getting caught up in the drug fix mode of our physical and mental healthcare system. As women it is even worse. As soon as I began menstruating I was given a prescription for what we’d now call PMS. Years later when meeting with a psychiatrist for depression she told me I was lucky I got off that med without being hospitalized and today that would be considered child abuse. I told her I usually flushed it down the toilet. I learned to not say what I really think of anything especially around family. Don’t spoil everyone else’s party by pointing out a different perspective.

Report comment

Thank you, Linda. I’m grateful I’m able to tell her story. And I’m sorry about your experience as a young person. Glad you mostly flushed the pills down the toilet! You knew better than the MD who prescribed them.

Report comment

Thank you. The honor you give your sister moves me deeply.

You also remind me to stay strong in my commitment to stay alive for my family.

I sometimes forget the weeks on end, in 1985, of hearing my fellow longterm inpatient’s wails after she was informed of her son’s suicide. She was kept in the solitary room but they kept the door open. Why she was in there at all, I’ll never understand. I vowed then that I would never do that to my own mother.

But I did forget my vow in 1990. I survived. I’ve not tried again.

Now, in acute withdrawal and with terrible tardive akathisia I want to break that vow almost every minute of every day.

Your article is a godsend.

Thank you for writing and having it here for all of us to read.

Report comment

Blu, thank you for reading my piece about Lucy. I am so profoundly sorry for your withdrawal agonies – and I’m just as profoundly grateful for your resolve to stick around for your loved ones’ sakes. I know (without truly being able to know) that it can’t be easy. The strength it takes is enormous. So is the gift of yourself that you’re giving friends and family. Bless you and, again, thank you.

Report comment

Amy, I know how you feel. I’ve been through what you’ve been through. And I would love to read your book.

Report comment

Thank you, Debbie – and I’m so sorry this is all too familiar for you. As for the book, I hope to finish it soon. Again, thanks.

Report comment

Beautifully and powerfully written, Amy! I want everyone I know to read this. I want to make a QR code for Lucy, and Catherine, and others and wear it on a shirt, plaster it around, etc. etc.

Report comment

Thank you, Carol. So much!

Report comment

An absolutely beautifully written tribute to your sister, Amy. I dearly hope you stay with your novel, if not to give your sister back the wings-and life- she had before psychiatry clipped them, then as a work of art that transforms that which previously seemed impossible or otherwise unimagined. Thank you for having the courage and compassion to tell this profoundly difficult story, and do so with unmistakable grace.

Report comment

Kevin, thank you so much for this beautiful comment. Working on the book off and on these past years has helped me shape my understanding of Lucy and made me see and comprehend her in new ways. Whether or not I wind up publishing it, it’s been a gift – and it was a gift to write this piece and hear from readers in the MIA community. So again, thank you.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your sister’s story. She sounded like a beautiful soul. It is true you never ‘get over’ trauma like that, you can only learn how to come into a sustainable relationship with it. Like the fellow from ‘a beautiful mind’ who learns to come into relation with his hallucinations without trying to make them stop. I relate especially to the physical issues being misdiagnosed. I had sleep apnea from a young age, and hypoglycemia that went unrecognized until last year. Now that I can sleep and am not having repeated blood sugar crashes things look very different, obviously. But I had to go outside of traditional healthcare and definitely outside of psychiatry to get this figured out. In psychiatry I was labeled up and down, just like your sister. I remember one doctor diagnosing my cyclothymic because I had a ‘bipolar flavor.’ Can you imagine someone medicating with insulin because after spending 15 minutes with a person a doctor decided they had a ‘diabetic flavor??’ It’s preposterous, and so dangerous. And yes, it remains tragically true that suicidal ideation — which is not the same as intent — is FAR less of a suicide risk than psychiatric care, especially the coercive varieties intended to make you want to live under duress ‘or else:’ so preposterous. All my love to you and yours.

Report comment

Thank you, Ryan! Stories like yours pierce my heart. I’m so sorry for all that you’ve been through, but I’m so grateful you’re making your voice heard. The dehumanization of people in the prevailing model of care is outrageous, and each time I hear or read of a case, I’m shocked but not surprised. Thank you again, so much, for reading my piece, posting your comment with love — beaming it back at you — and pushing for change.

Report comment

Amy, I’m so very sorry for your loss and all the pain that Lucy endured. I’m glad that you are writing a speculative fiction story about how her life may have gone under better circumstances. The book sounds like a good read as well as a heartfelt homage to your sister and all she endured.

On another note, I just listened to a several episode podcast about a man with TLE who killed someone and has been in prison since he was 16. No one believes the diagnosis of TLE. We all need to open ourselves to the many ways that humans can function and things can go wrong. Entertain multiple solutions and possible causes…..please. Brava for your courage.

Report comment

Thank you, Ann. The book is definitely as intense as it is strange, but I’d like to think that it’s a decent read – though its publishability (not a word, but it should be) is the last thing that matters to me. And yes, everyone’s different. Multiple possible causes for distress, and multiple solutions. Seems so obvious, or it should be.

Report comment

Hi Amy,

Beyond sad. Yet another victim of the evils of psychiatry! These stories that come up on MIA are becoming too numerous to mention. I am glad, though, that you are telling Lucy’s story here and by writing the book which will, no doubt, be therapy for you… (I lost my son to suicide–no one in the system willing to help him.) I am attempting an essay on how and why we have gone down a very wrong road since the Enlightenment era and how this has led us to so many present day dilemmas, as in psychiatrists being the caretakers of the soul!

One more Unfortunate

Weary of breath,

Rashly importunate,

Gone to her death !

From “The Bridge of Sighs” ~ Thomas Hood

Report comment

Louisa, I am so sorry for all you’ve been through – and I’m so grateful to you for reading my sister’s story. Thank you for your compassion. Yes, writing the book has definitely been therapy – probably one reason when it’s taking me forever to finish it. But it is nearly done, whatever that means. And what a beautiful quote from Thomas Hood. Again, thank you.

Report comment

My condolences, Amy, on both the deaths of your sister, and your husband. Both must have been extremely hard on you … especially given the lies, or now claimed ignorance … of our current “mental health professionals.”

Report comment

Thank you. Hard, yes. But I was fortunate, with both losses, to be supported by friends and family on my bumpy and ongoing path forward. And yes, far too many lies – or at the very least, failures to recognize harm due to longstanding blinders that shut out the truth.

Report comment

I think the book you’re working on sounds interesting.

Report comment

It’s been interesting to write! Not sure what anyone else will think of it, but thank you. Almost done.

Report comment

Amy, thank you for sharing Lucy’s story.

I am not a member of the Church of Scientology, but I do attend events hosted by the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) in Clearwater, FL and have toured CCHR’s museum, Psychiatry: an Industry of Death, many times.

Many people believe CCHR is a “front” for the church, but that has not been my experience at all. I have tremendous respect for CCHR’s accomplishments, staff and volunteers.

The museum reveals the truth and contains powerful visual images.

Whenever I read stories like Lucy’s, those images, along with ones from my own experiences, play through my mind. The lack of compassion breaks my heart.

I think it is important for those who are pro-psychiatry advocates, to consider if labels from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders cause professionals and caregivers to dehumanize the consumer?

“Dehumanization is the denial of full humanity in others along with the cruelty and suffering that accompany it…A practical definition refers to it as the viewing and the treatment of other people as though they lack the mental capacities that are commonly attributed to human beings….Dehumanization is one form of incitement to genocide…It has also been used to justify war, judicial and extrajudicial killing, slavery, the confiscation of property, denial of suffrage and other rights, and to attack enemies…”

In my opinion, the system is slow to change, because pro-psychiatry advocates who support organizations like NAMI turn a blind eye to the dehumanization of consumers and instead, advance agendas in favor of forced psychiatric treatment.

The system will only change when all advocates are able to handle the truth and work together.

Kind Regards, Maria

Report comment

Maria, thank you so much. I know from your own writing some of what you’ve gone through, and I agree that that such stories (and there are far too many of them) point to a staggering lack of compassion. It should not be hard to see and treat each individual as a human being deserving of understanding and respect. And you’re right – the folks at NAMI and company need to recognize this as much as anyone. Hopefully, eventually, they will.

Report comment

Everyone deserves space to be themselves.

Report comment

Amen.

Report comment

This is a beautiful tribute to your sister. It brought tears to my eyes.

I’d buy your book.

Report comment

Thank you so much.

Report comment

I’m sorry for the loss of your sister. I lost a friend in a similar situation and don’t have the talent to tell the story as you did here, so thank you for sharing.

(and I’d read that book. Maybe you’re right that its conventionally not publishable but I’ve read some amazing self-published works so I hope you pursue it if you wish to)

Report comment

I’m sorry you lost a friend in a similar way, but I’m grateful you read my piece. Also grateful for your openness to reading my out-there novel. I may indeed wind up self-publishing, though writing the book has been a blessing unto itself. Will see.

Report comment

Dear Amy, thank you for your willingness to let us follow your journey through all the love and losses of your life. I met Chris decades ago and always think of him as a kind, brilliant, loving person. Sending you care and love.

Report comment

In July last year, I started on PARKINSON DISEASE TREATMENT PROTOCOL from Natural Herbs Centre One month into the treatment, I made a significant recovery. After I completed the recommended treatment, almost all my symptoms were gone, great improvement with my movement and balance. Its been a year, life has been amazing

Report comment

Oh Amy, as always you are able to

put to words the deep emotions and thoughts of the survivors of suicide loss. You have an amazing gift. I want to read the story about your sister but I don’t know where I can find it.

Report comment