According to a recent article published in the British Journal of Social Work, the way service users perceive resilience is influenced by personal, social, and professional factors. The study, led by Harry Bark from the University of Bath, also revealed that these perspectives are subject to change and can be influenced by life experiences.

“In the context of mental health recovery, resilience is understood by individuals with experience of psychosis as a varied and multifaceted trait and resource,” Bark writes. “Personal, social and professional factors all inform an individual’s experiences of resilience which, crucially, must be viewed as a dynamic and changing perspective that can be fundamentally altered through life experiences.”

The current study aimed to investigate views on resilience among individuals who have undergone psychosis. To accomplish this objective, Bark gathered articles on recovery and resilience and identified common themes. For the current research, studies were considered if they were peer-reviewed, written in English, focused on adult service users, and used qualitative or mixed methods. Additionally, studies had to be published in 2012 or later. Research that did not meet these criteria, such as studies that were not published, used quantitative methods only, were published in a language other than English, focused on professionals rather than service users, or were published before 2012, were excluded from the study.

The current study aimed to investigate views on resilience among individuals who have undergone psychosis. To accomplish this objective, Bark gathered articles on recovery and resilience and identified common themes. For the current research, studies were considered if they were peer-reviewed, written in English, focused on adult service users, and used qualitative or mixed methods. Additionally, studies had to be published in 2012 or later. Research that did not meet these criteria, such as studies that were not published, used quantitative methods only, were published in a language other than English, focused on professionals rather than service users, or were published before 2012, were excluded from the study.

The final review included 12 papers with a total of 179 participants. The age range of the participants was 18-75 years. Most studies (9) used purposive sampling to select participants based on specific characteristics, while two studies used convenience sampling, and 1 study used a combination of both methods. All studies used 1-on-1 interviews to collect data, with ten studies using semi-structured and 2 using unstructured interviews.

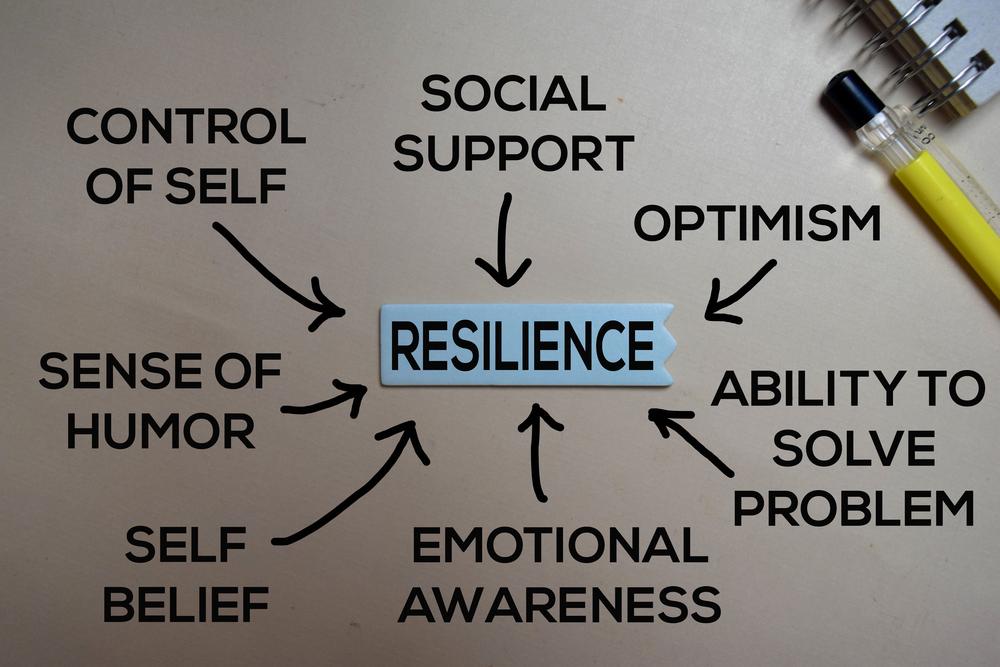

The current research conducted by Bark identified three themes and eight sub-themes related to resilience. The first theme, “Personal Factors,” includes three sub-themes: personal responsibility, use of experience, and coping strategies. Of the 12 reviewed papers, personal responsibility was discussed in 5 of them. The study participants’ understandings of personal responsibility included recognizing distress and triggering situations, crisis planning, and seeking support. They also framed personal responsibility as an approach to stress that involved ‘living in the moment’ and focusing on the present.

The “use of experience” was discussed in seven out of twelve studies that were included. The use of experience encompassed reframing past episodes of psychosis as opportunities for learning and growth while emphasizing challenges and obstacles as stepping stones for development. One participant highlighted that without experiencing extreme distress in the past, it would be impossible to determine one’s level of resilience.

In 6 out of the 12 included studies, coping strategies were discussed. The subtheme highlighted the importance of having a plan in place to deal with distress and using positive reframing as a conscious way to identify positive changes that occurred after experiencing a first episode of psychosis. Additionally, the theme included the idea of re-establishing emotional structure after psychosis through “non-activities” like relaxation and meditation.

Bark identified a second theme, “social factors,” with three subthemes: peer support, social relationships, and contribution. Out of the 12 studies analyzed, seven of them considered peer support to be an essential component of resilience. Peer support helped create a sense of community among the participants and made them feel more confident in managing distress in the future. It also helped to alleviate the stigma and feelings of alienation that many participants experienced due to their encounter with psychosis.

For many participants, social relationships such as family had a grounding effect. They pointed out that their responsibilities towards their family motivated them in their recovery journey. However, the author notes that family could also act as a barrier to resilience if they have a poor understanding of psychosis and the recovery process.

Out of the 12 studies, four studies talked about contribution. The participants discussed the contribution in two ways: helping others recover from episodes of psychosis and finding employment. The ability to contribute in these ways boosted the confidence and self-esteem of participants while also making them aware of their own needs.

Among the themes identified by Bark, the last one was “professional factors,” which consisted of two subthemes: relationships with professionals and structured support. Out of the 12 studies analyzed, five of them discussed relationships with professionals. The participants highlighted the importance of seeking professional help during crises, especially when other coping mechanisms failed. Emotional support, empathy, and respect were crucial in building good relationships with professionals. However, the author cautions that generic approaches by professionals could hurt both recovery and resilience, leading service users to abandon professional help as an option when faced with frustrating interactions.

Out of the 12 papers included in the discussion, structured support was mentioned in 3. Many participants emphasized the significance of professional, structured support from empathetic and compassionate practitioners for their recovery and resilience. However, one participant viewed forced structured support as a source of distress instead of resilience.

The author acknowledges two limitations of the current research. Firstly, the quality of the included papers was not assessed, potentially leading to the inclusion of studies that lacked validity. Secondly, the included papers had varying ways of recording demographic information, which prevented the current research from fully exploring how demographic factors, such as race, affected perspectives on resilience. Additionally, it’s worth noting that the recent research only included papers published in English, which significantly limits its generalizability to non-English speaking populations.

Studies have indicated that training on resilience can positively impact mental health and overall well-being. Similarly, becoming a peer support worker has been found to enhance personal insight and resilience, which ultimately leads to better recovery outcomes for service users. However, some research suggests that the notion of resilience may not be applicable to all cultures, as it can be perceived and interpreted differently. One study has highlighted that the Western perspective on resilience may not be relevant to non-Western subjects.

****

Bark, H. (2023). Resilience as Part of Recovery: The Views of Those with Experiences of Psychosis, and Learning for British Mental Health Social Work Practice. A Scoping Review. British Journal of Social Work. (Link)

Many questions here. 1) Does “service users” mean people taking Anti-Psychotics or a mixed group with some not taking A.P.s? What about Super-Sensitivity Psychosis(SSP)? How cruel to add the burden of SSP to a naturally occurring psychosis and then measure the Pt’s resilience! 2) How can effective discussion of resilience leave out factors of physical health, including nutrition? Hasn’t society already acknowledged the importance of nutrition to well-being which surely translates to resilience? Isn’t that why we have the school breakfast and lunch programs, to improve children’s resilience to the stresses of their day? What about the concept of Comfort Food? Here is a link to an article re: nutrition and mental health that I think is relevant : http://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.598119/full. 3) Have I misunderstood the point of this article? Why are we overlooking the relevance of our holistic nature? Does it make sense to solely focus on social support when we are neglecting the physical health of the organism? It’s hard to be emotionally resilient on an empty stomach, or on a diet of sugar and toxic food additives, or lacking in the nutritional oils that calm the Central Nervous System.

Report comment

I get the impression the article reviewed sounds like a fishing trip. Like there was no hypothesis but let us find out.

And to me it stands out the unstated relationship between resilience and recovery. At the bottom of this post says training can positively affect the latter, but that is training in resilience…

You have to train to do a marathon but in MH you do not want to hear: “You need to learn to hold on better! It can increase your chances of recovery!”.

I would not say that to a person with diabetes who needs insulin: “You need to learn resilience when your sugar is too high or too low!”.

Or to a person with hypertensive headaches: “You need to develop resilience when you have tinnitus, dizzines and headaches, the treatment does not fix it all!”.

And I am not arguing for treatment, on the contrary, arguing for resilience in MH treatments sounds to me like an admission that they are ordeals, even torture, with little, no benefit or more harm than good.

And that could justify bringing resilience in any treatment as something imputed as PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY of the sufferer. Blame the patient for being too brittle, a self reinforcing loop if admitted by the sufferer. And a little callous when one’s suffering and WANTS help. “You need to toughen up, just we call it resilience, we don’t want to tigger you… again”.

And bringing coping suggest to me, going on a limb, the typical unstated: “You have to cope with the treatment, otherwise you won’t recover”. “Endure my gasslighting, verbal and psychological abuse, I am here for you”, “I don’t care about the money, I, I, learned to cope with that, and I hope you can cope with paying me, even be gratefull to me for paying me, it’s a good investment for you”. Which is typical in psychotherapy: “Therapy hurts…”

Which sounds to me also like typical old libertarian way of thinking.

Admitting that propping up resilience when there is no effective treatment, assuming it requires one, big if, might be the safest strategy. But how to do that?, without further psychologization or psychiatrization?.

Not denying the suffering either. Precisely perhaps the intersectionality between personal responsability, coping and resilience propaganda on sufferers. They are desperate and get little help, perhaps.

All of that psycho babble, not criticizing this post though, sounds not unlike the DSM:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2023/10/maid-and-mental-illness-an-interview-with-dr-jeffrey-kirby/

Which I analyze in informal logical way, poorly, if you are into that.

Report comment