Deborah Kasdan is author of Roll Back The World: A Sister’s Memoir, in which she describes her extraordinary late sister Rachel—poet, musician, free spirit—and her decades-long journey through psychiatric treatment until, finally, she found a place of peace and community.

Kasdan is a longtime business and technology writer who pivoted to memoir writing on a quest to tell her sister’s story, joining the Westport Writers’ Workshop. Her book, published in October by She Writes Press, is a moving and nuanced portrait filled with love and grief, candor, and complexity.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Amy Biancolli: Deborah Kasdan, thank you for speaking with me today.

Deborah Kasdan: I’m glad to be here, Amy.

Biancolli: This is obviously a big topic. It’s deeply personal. The book covers so much ground, so many years: your sister’s entire life, your relationship with her, the family dynamics. There’s so much in it, and she was an indelible person. I know we don’t have time to dig into every last piece of it. But for a start, if you could tell us who she was, what you loved about her, so that as we get into this conversation and dig a little deeper into all that happened, people will have a sense of Rachel and what she means to you, still.

Kasdan: Well, Rachel was my big sister, first and foremost, born three and a half years before I was. She was a leader to me. She was a free spirit that became increasingly clear as years went on. She led me places. She advised me on many things—what to read, what to wear, what teachers to take, and she was a buffer between our parents and me, because she was the first child and she pushed the limits. And when she fought with them and got concessions about what we could or couldn’t do, it took some of the heat off me, it gave me a little bit of space.

And as you said, she was musical. She was artistic, poetic. She was my role model for a long time.

Biancolli: She was an inspiration.

Kasdan: Yes. Especially with the writing.

Biancolli: You describe her youth, and you describe the time she spent in Israel, traveling, having adventures, working in a kibbutz. It was after she came back when she had her first psychotic break, right? She believed she was being followed by two men from New York City to San Francisco. So could you talk about that a little bit?

Kasdan: Well, that was the first time I saw anything that made me wonder whether she was okay. My parents had been on her case a long time for a few years since she got back, wanting her to settle down and have some direction and go to college. She didn’t want to go to college, she went to work. She was very impulsively dashing around the country. So she came back from San Francisco when I was still in high school. She sat down and told me that she was being followed by two men.

Now she had come back from San Francisco because her boss had called my parents and told her something wasn’t right. But I still didn’t know what that was. I didn’t know what that meant. As far as I was concerned: my parents, her bosses, [maybe] they didn’t like her lifestyle, maybe the way she dressed. You know, she was kind of a bohemian. So I didn’t know what that meant. But then when she told me personally that two men were following her, I could see it in her eyes that she was afraid. I knew something was wrong. And maybe my parents had reason to be worried, something which I had resisted believing.

Biancolli: You have this memory that you describe in the book [of you] as a family watching Khrushchev give a talk on television to the U.N. And your dad had been an activist, a leftist. He was very liberal, and apparently he was on the FBI’s radar, because in the middle of watching this, they literally showed up at your doorstep, right? I mean, what a story. How could that not have fed into what ultimately led to her first psychotic break? It’s almost logical.

Kasdan: So logical that when my daughter read that—I don’t think she remembered when I told her about it, but she read it—she said, “Well, maybe she was involved in political activities.” So I finally did write to the FBI, and they had no file on her. So she wasn’t being followed.

But yeah, my dad and my mom, too, were involved in left-wing politics. And ACLU was considered a communist front, and they were active in that, and my father had actually joined the party when he was in college—when a lot of people did. They called themselves fellow travelers, which means they would help out.

When some communists had to go underground, I think they helped out. Gave them a place to stay. So, of course they were on the FBI list. And every time my dad took a new job, they showed up to let him know that they knew where he was, and please, would he name any names? And of course he wouldn’t. That’s basically what they wanted.

So yes, [the FBI showing up during the Khruschev talk] must have fed into it for her. I thought it was a big joke. It was just funny. Me and my younger brother kind of laughed it off. But she was older. She was already a teenager, and she was very well read, very aware of what was going on. And she must have felt the danger that was inherent in this. She took it seriously.

Biancolli: And of course, now we know so much. There’s so much research connecting trauma with psychotic breaks. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 23, and she was ultimately hospitalized many times, right? She was in and out of the hospital.

Kasdan: Many, many times. Yes.

Biancolli: And how did you feel as her sister with all of this happening? When she was first hospitalized, and what were some of the changes that you might have seen affecting your sister after she was first put on drugs and committed?

Kasdan: Oh, she changed after she was medicated in St. Louis. She changed utterly, just totally. The active dynamic person. She just became flaccid, she started getting tardive dyskinesia, the neuromuscular side effects of the narcoleptics. She was still feisty. I mean, when she had her privileges, she wanted to do what she wanted to do. She had a boyfriend who was a former patient at the hospital.

So she led this kind of life that I wasn’t part of, and she was in and out. She still had opportunities to do things but she lost all her vigor, you know—her eyes weren’t the same, and she gained a whole lot of weight from the medications, of course. She still had interest in drawing. She was still writing poetry, and some of the poems in the book [were written] during those first few years. So she maintained some of her interests. But she was more tractable. She wasn’t as oppositional as she used to be, at least not overtly, that I could see. So it was hard, you know. And the situation at home became pretty chaotic, with my parents and her. Nobody ever agreed on anything. So I became kind of depressed myself. I didn’t know what was happening. It was very confusing.

Biancolli: Well, how can it not be? My late sister, Lucy, wasn’t diagnosed with schizophrenia, but she was diagnosed with a million other things, and she spent years being hospitalized. Even though there are obvious differences, I was just so struck by so many parallels, and one that I wanted to ask you about was this: how difficult it is to see the change in your sister. Lucy was my big sister. She died in ’92 by suicide. The transformation was so hard to watch, because she was an aspiring concert pianist. So when I grew up, she was my genius older sister. Then, as soon as she started being treated, and being hospitalized and drugged—around the same time, she stopped being able to play the piano because she couldn’t concentrate. And in the context of the time, I didn’t really know what was happening. “Oh, that’s her ‘mental illness.’” But, looking back, well, almost undoubtedly, that was the drugs she was on.

So not to go off on this little side conversation about my sister, but I was really, really, deeply moved, because I get it. You’re watching your older sister, who you grew up admiring, and oh, my gosh, she was just everything to me. And then it was like the mute button was put on her in a lot of ways, not so much on her personality, but what she was able to do. And it’s hard. It’s really hard to see that happen to somebody you love.

Kasdan: Yes, she was putting together a book of poems those first years, and I think the project fell apart. The poems were made, of course. I have them. But you know, the idea of publishing them–somebody asked me recently, did she ever publish? No, she didn’t. But she would have, I believe, just like your sister would have given concerts, you know?

Biancolli: Another question I have for you in that regard: I’ve never stopped asking what ifs—you know, what might have happened in an alternate timeline. Well, what if something had changed? If this had changed, if that had changed? Would she have gone on to a career as a pianist? And would your sister have gone on to have a significant career as a poet? What if? Do you ask yourself that?

Kasdan: I ask the what ifs more in terms of what if her early life had been different? I have these counterfactual scenarios that would have prevented that anger and that lack of trust that fed into whatever caused her psychosis and remained. If she had not been hospitalized, and given all those medications, and had a treatment that was non-judgmental and was supportive: I think she might have continued her poetry. She was also interested in art. I mean she did switch around her interests a lot.

But I think she would have found a community, some bohemian community, and lived some interesting life and been productive and creative. She loved the kibbutz work. She loved the outdoors. I could see her in California, maybe on a commune, maybe in an artist community. I think she would have had an interesting life. She did love travel. She was always traveling. And I think she would have continued to do that.

Biancolli: Well, it’s one of the things you bring out. And one later aspect of her story that you bring out is that ultimately she did find community. She wound up going out to the Pacific Northwest the period before her death at 59. She connected with a case worker. But he was compassionate, and he also saw inside her, in a way—saw her in a way that so many other people in psychiatric treatment seemed not to—and he saw the creative spirit and encouraged her to get back to her poetry, right?

Kasdan: He did, he did. You know, she was so, so damaged by all her hospitalizations and medications and whatever, that the people in the hospital had a hard time believing her educational level and her past—and I see it in the notes I obtained from Oregon’s State Records, a big carton full of hospital records. And they just saw nothing of who she was. Because she didn’t talk to them. She did not bear fools lightly. You know, she just ignored them or blew them off.

So Steve, this case worker who helped her, wanted to get her out of the back ward of Dammasch State Hospital in Oregon. And she was in a trial program with this agency in Eugene, and as part of this trial program, she had a janitorial assignment in the agency’s reception area. He went to check on her. And he found the poem she had written on the typewriter there. That was the poem “Water.” He said, “I’m not a poet, but this sure looks good,” and he gave it to a senior colleague who read it and said, “Yeah, this is good.” And Rachel was not performing her janitorial duties that brilliantly. You know, there were limited places for this work-residential program. So at a staff meeting, he had his senior colleague, who was also a poet, read this poem. And he said you could hear a pin drop, and they accepted her into the program. He had to do a few maneuvers to get her in. You know, the big issue is getting housing, and it took a few tries before she found a place that she could stay in. She was not an easy tenant. But he respected her so much.

They talked about poetry, and books, and ideas. I just recently saw again his case notes in the Oregon State Records, and he said [they] talked about Ann Sexton and Sylvia Plath, and “she really knows her stuff.” Nobody in all those years in the hospitals ever talked to her about anything literary or intellectual. And he understood how people could seem impaired, or maybe just different, and also be very talented. So he understood this type of neurodiversity—whatever you want to call it—and he was not put off by her lack of trust. She could be very suspicious of people, with good cause, considering what was done to her, but she wasn’t able to control it at all times. So that sometimes prevented her from getting help that she needed. But he was able to get around that.

Steve’s a good guy. He’s a good guy. He gained her trust by seeing her as a person, understanding her interests and overlooking all the things that were obnoxious about her. You know, her behavior could be very off putting, and that didn’t bother him. He just accepted her.

Biancolli: That’s a beautiful story. And of course in the book, this comes near the end, after your descriptions of all that she’s been through—and not just her hospitalizations, but she spent time unhoused, living on the streets at different points. And you also describe the impact on your family. But coming around to this period at the end where she found community, she actually had her own little cabin, right?

Kasdan: It was a little house in this no man’s land between Eugene and Springfield. It wasn’t really zoned, and the agency had a few cabins in the woods. So she wasn’t totally alone, but she had her own space and her privacy, and it wasn’t far from the university—and she loved sitting in on classes. And she loved to walk. She loved nature. So her favorite thing was just to take walks. This little house was near the Willamette River, and she made her way to the banks of the river. She had to walk across property that was owned by an Oregon factory, and they took an interest in her. So she knew how to make friends too, and so she just loved to. She loved that area. That was perfect for her.

Biancolli: I love that little story—again, going back to the point that she was finally being seen in a way that she wasn’t as a psychiatric patient. We see this so often: as soon as somebody gets labeled, treated, drugged, hospitalized, the system and society at large stops seeing and stops listening. And I just thought that was such a beautiful example of what happens when we listen. Nowadays, we have things like Open Dialogue and the Hearing Voices movement. Do you wonder how those might have helped your sister?

Kasdan: Yes, she needed to be accepted, she needed a place where she wouldn’t be judged. Everybody was so quick to judge what she did. And my mother, I think that she was just so afraid. She wouldn’t even let friends go visit her. My mom wasn’t a mean person, but I think that was something coming from her own fear. So I think she would have been helped by peer specialists, which they didn’t have, then, that I know of. And I think it would have helped the family to be able to talk to peer specialists—if they had talked to people who had been through the system and survived it, so that we wouldn’t be so afraid of what was happening, and we wouldn’t distance ourselves so much.

I think that the family is a wasted resource. You know, she had three siblings and two caring parents, and we all loved her, and wanted to help her, but we didn’t know how. And I think if somebody had sat with the family, and given us reasons to hope and to understand examples of people who get through this, examples of recovery and healing, then I think that we could have mobilized in a more constructive way. What we tried just didn’t work out because we weren’t educated ourselves. I mean, we were educated as much as anybody was for those times.

Biancolli: Families still struggle to be seen and heard, like when they’re advocating for someone they love, but then it was even harder—because there was less awareness. Is that something that we should still be working on? On engaging families more? I know there are programs that involve peer workers coming in and talking to families and things like that, and there are more groups that are forming among family members themselves.

Kasdan: Trust and being non-judgmental were the main things that my family could have learned. Rachel was very difficult. I mean, she was very oppositional with my parents, and maybe she couldn’t have lived with them, maybe she had to find an alternative placement. But certainly, when her siblings were adults, and wanted to help, I felt horrible that I didn’t feel I could have her near me. I had my own family, and I felt terribly guilty about that, which brings me to the issue that I kind of sense today—where parents want to be in charge of their adult children who are vulnerable, for all kinds of reasons, and the siblings may or may not disagree with them. So you may have different viewpoints within the family, and the parents may not always be able to help. That’s where you need community, outpatient [programs] or facilities that can help with housing, and job coaching, or education coaching if they’re in college still. And then siblings might be able to support those efforts.

We were separated geographically through some odd circumstances, and maybe that hurt Rachel’s situation—because even if you’re not living with your family, even if you’re not really close to your family, you want to be a part of the network when there’s a wedding or a Bar Mitzvah or an engagement or something. You want to be part of that. So I think there’s a big loss when there’s this geographic separation that doesn’t have to be maintained. I think it’s good to try to keep a viable network going, and I think families need support to do that, and not just parents, siblings as well.

Biancolli: I understand guilt after losing a sibling, after losing anybody you love to any kind of difficult circumstances. I’ve felt that guilt after each of the suicide losses that have affected me, and you can say, rationally, “okay, I did my best.” It’s easy for someone like me to say to you, Deb, that you shouldn’t give yourself a hard time because you did your best. But I also understand where the guilt comes from. And I think that’s such a huge piece of the family’s, the loved ones’, experience when someone is in distress and you want to help, you want to stay connected with them. In an ideal world, you want to maybe wave the Magic Wand and make everything better, but you can’t. I totally get it. I feel it, I really feel it, because this is part of the family experience that I think people don’t always talk about or understand, and you’re very open about your feelings of guilt in the book.

Kasdan: I think that if there hadn’t been such stigma—and there’s still a lot of stigma—I wouldn’t have been so closed off about it. I didn’t talk about Rachel, at work or with my friends. I didn’t deny her existence, and I occasionally found opportunity to mention her. But you know, it wasn’t a day-to-day, week-to-week thing that I would talk about Rachel, and I think closing off that part of myself made the guilt worse. I think part of the guilt was not acknowledging her existence in the full sense. Again, I didn’t deny it, but I didn’t really make her a part of my life.

Biancolli: I get it. I understand. And again, I know your story’s different, her story is different. But I understand, and I’m also wondering about writing the book—because I’ve written a couple memoirs of grief. And I’ve always found that whenever I write personal works, addressing grief and loss, it’s a way for me to create a narrative and understand my loved ones better. And I wondered if you had the same experience with what you learned about Rachel. What came to the fore? Were there healing aspects for you in writing the book, and was that one reason why you wrote it?

Kasdan: Well, it certainly brought me closer to her, because I just immersed myself in her—particularly her letters. And [there were] letters I had never seen before to my parents. I learned that there was love between her and my mother, and so much of my guilt was bound up with my relationships with other members of the family. But when I was able to step back and see them having their relationship that I was in the middle of, that was very healing. The letters between her and my mother, reading the hospital records—as terrifying as you can imagine.

Yet I saw a very strong and independent-minded person. The poems, through the years: they did get darker and darker as time went on. But that she never gave up her writing was very inspiring to me, even after all she had gone through. She sent me, once—she was maybe being transferred to another hospital—her journals for writing her stories. Because she trusted me to keep them, and I thought about that. I said, “We’re connected with the writing, that connects us somehow,” and that was very healing. And to be writing about her, it almost felt like I was writing with her, and that was healing. That brought back, you know, the older sister I admired.

Biancolli: And again, I completely understand, because I’ve had that experience as well. I was actually going to ask you whether you felt like you were, in a way, conversing with your sister. Visiting with her. Because whenever I write or even talk, it’s like I’m learning about the people I love who aren’t here any longer. And in a weird way—and you tell me if this sounds at all familiar to you—I almost feel as though I’m still maintaining a relationship with Lucy. Like, every time I write about her, I’m having a conversation with her, I’m learning from her, I’m hearing her voice. This is, at least, my experience of grief, and I’ve never heard that talked about. Do you get what I’m saying?

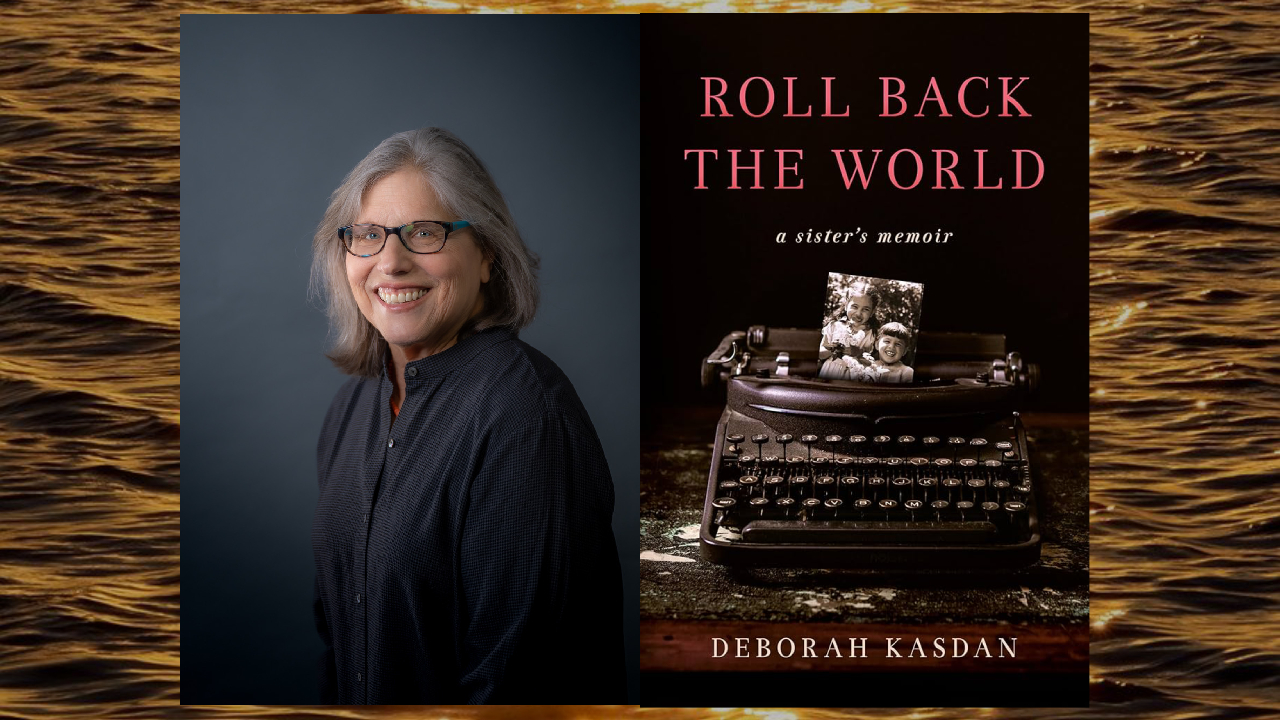

Kasdan: Definitely, definitely. And when the publisher’s designer came up with the cover art, I said, what? It didn’t make any sense. But the more I sat with it, the more I understood it. They had asked for a picture of the two of us together. So I [had a photo] when we were little, 6 and 3, maybe, and she took this picture and the designer and put it behind the platen of the typewriter. So it’s coming out of typewriter.

And yes, we’re writing together. And I’m writing about her, and I’m talking about her. And she gets to have her own say, because her letters and her poems are in the book. So, yes, I feel it was a joint effort. Then every time I talk about the book, I’m talking about her and repeating her name, Rachel Goodman. I got in touch with people who knew her who I didn’t know, and we talked about her. And then having the book is a reason to discuss her and share our memories.

Biancolli: I know Rachel. I know Rachel Goodman from reading the book, and that’s the other beauty.

Kasdan: Yes, because she was so marginalized. I just weep at the amount of marginalization she endured, being homeless, brought to the emergency room, arrested. And she was considered a street person, and to me—to have her name out there, to have other people know her—is just wonderful.

Biancolli: I also wanted to ask you about the push, now, in different parts of the country for forced treatment. Obviously in New York City, you’ve got Eric Adams pushing to have unhoused people hospitalized, and then you’ve got everything going on in California. How do you feel about that? Does that break your heart? Does that make you think of Rachel?

Kasdan: Yeah, one of the reasons we left her on the West Coast when she landed up there, I thought if she was near me—I live not too far from New York City—she would have made her way to New York City, and she would have been one of those homeless people in New York City, at least for a while, between stays with me or in respite places.

I mean, the irony is they don’t even have places when they sweep them up and put them in the hospitals. Hospitals can’t keep them, so they just go back. It’s a fake solution, basically. And I hear that in California, the counties that are supposed to implement those care courts are pushing back because they don’t have the funding to do it. So it all just goes back to no funding. They’re not even a real solution.

So it’s just political theater, if you ask me. That’s my opinion. It’s just political theater, and the real solutions, which are community-based outpatient treatment, community-based housing solutions, and peer counseling, coaching—that’s where the money should be going. So, yes, it breaks my heart when people just, you know, pass the unhoused person on the street and say that they’re a nuisance to their lifestyle. Their quality of life—that’s the term they use. They spoil the quality of life for their community.

Well, every person deserves a quality of life—and when you hog all the resources, you’re depriving other people of a quality of life.

Biancolli: And when they walk past someone, they don’t even want to see someone on the street. They don’t want to hear them.

Kasdan: Right, and there’s a person there. There’s a person with a history. There’s a family that loves them that may not have been able to help them. But there’s a person with talent and hopes and dreams and disappointments.

Biancolli: So you included your sister’s own voice in the book, her letters and poems, for instance. How important was that to you, since she was someone whose voice wasn’t heard?

Kasdan: When I first started writing, I was so in my own head, trying to figure out what I felt and believed. I had read her poems, but people who saw the initial manuscripts wanted to see more Rachel. And I said, well, I have her letters. I’ve been reading them. So I took care to excerpt them, weave them into the story, and I realized how important it was. I didn’t start that way, but I developed it, people encouraged me, and I became more emboldened as I did it. Yes, her voice works. And then picking the poems out to include became very meaningful to me.

Biancolli: One of them, a really beautiful poem, closes the book and inspired the title, Roll Back the World. Could you read that for our listeners?

Kasdan: Yes, that’s the one that she wrote when she was supposed to be mopping the floor. So keep that in mind. I do like to imagine—if I can just preface this—that as she wrote this, she was thinking about her time in Israel, because she was near the Mediterranean. And I like to think of her on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea when she wrote this:

In delicate aroma

I walked the beach at night

Where the moon

Joined sand into sea

And the waves rolled back the world.

Here shattered night

Makes clean each grain it meets

Where yesterday

A sand-crab walked

And found its mate for safety.

Roll back the world

For so I have been free

With a crab

And the sea

And my shadow on the moonlit beach.

Biancolli: That’s beautiful.

Our guest today was Deborah Kasdan, author of Roll Back the World, A Sister’s Memoir, recently published by She Writes Press. For more information, see www.deborahkasdan.com. Deborah, thank you again, so much. Thank you for reading that beautiful poem by your sister Rachel. Thank you for writing the book, and thank you for joining us here at Mad In America.

Kasdan: Well, thanks Amy, for having me. I really enjoyed speaking with you. It’s very meaningful.

Biancolli: To me as well.

***

MIA Reports are made possible by donations from MIA readers like you. To make a donation, visit: https://www.madinamerica.com/donate/

Amy, that was a beautiful interview and book review, you were so empathic and understanding. God bless, to Deborah Kasdan and her family … and I will say, it’s sad how much our paternalistically set up systems want to destroy the strong “big sis’s” of our society.

Report comment

Rachel’s poem is incredibly beautiful, thank you.

Report comment

Reminds me of my brother. He was so intelligent but was labeled with a psychiatric illness and hospitalized on and off from the age of 25 onward. He died of respiratory failure and undiagnosed aortic aneurysm because no one at the psychiatric hospital believed he was ill.

A vice director of the hospital said he was surprised that he made it to 69 as the drugs can cause so many physical problems. They knew. This was the year 2000. Nothing changes.

On another note I find that with even a terminally chronic physical illness like CHF that the medical profession has tunnel vision and everything that could be wrong is due to the diagnosed illness and they don’t take into account that other things could be causing illness issues. In those cases hospice is preposed as no one cares to delve into proper diagnoses.

Report comment

You lost me at the fbi file. You think they are obligated to tell you the truth instead you buried her in tons of garbage…try walking down the street of toronto or any city aline as a young woman see if you are not treated like a piece of meat especially by doctors bent on flooding their markets with state sponsored crime sorry may read it all someday but I doubt it.

Report comment

Aren’t you cute sibling rivalry jealousy hatred and vanity. Flogging the dead your speudo compassion of never letting up on your prejudice and discrimination ….as if violence against young woman doesn’t exist or human trafficking and stalking ….to so invalidate reasonable fear and years of her life wasted someone better than you….Doctors particularly as in neomengeles like athletes and jealous journalists with a stroke of their pen can destroy your life and take 44 years making libel slander child endangerment printing false news exposing a rape victim a bad hair day for media I don’t believe a word of this therefore I’m not wasting my time on it like all of you wasted her life and tortured her…you don’t have to print this either I don’t care..no one takes responsibility for their crimes all want impunity before the law no one is normal free of symptoms try psychopathy there is no cure.

Report comment

The laws criminalizing the homeless are chilling

Report comment