Michel Foucault begins his work on the history of modern medicine, The Birth of the Clinic, with this enigmatic statement: “This book is about space, about language, and about death; it is about the act of seeing, the gaze.” Here, he coined a term which has become commonplace in the sociological study of medicine: “the medical gaze”. For Foucault, clinical observation—the way in which a doctor examines a patient—is not scientifically impartial. It is conceptual, invoking a latent theoretical grid which narrows potential interpretation. It is a kind of language, with an often cumbersome grammar. Nor is it socially impartial. The gaze surveils us. It contorts our lives into its awkward categories, often injuring us in the process. Foucault writes: “To look in order to know, to show in order to teach, is not this a tacit form of violence, all the more abusive for its silence, upon a sick body that demands to be comforted, not displayed?” I’ve attempted here to write my own essay about this gaze—about this language and its violence.

As a 20-year-old nurse, Rosie Tilli developed mild depressive symptoms amidst her city’s strict covid lockdown. Her GP prescribed Lexapro and immediately she suffered severe emotional numbness. She was reassured that the numbness was a benign reaction to a new antidepressant. Begrudgingly she continued with Lexapro and was even recommended a dose increase. She went on to develop disconcerting symptoms like visual snow, tinnitus, and complete genital anesthesia. These symptoms continued for months after stopping the medication. Rosie was understandably panicked. She was calling her mother constantly, asking if she would be okay. Although her parents fully support her now, they were originally skeptical. Is this kind of injury really possible?

Rosie explains: “My cousin is a pharmacist and she’s telling us ‘oh, it can’t do that. I’ve taken Lexapro before and that doesn’t happen'”. Alarmed by Rosie’s distress, her family set up a group meeting with Rosie and her psychiatrist. The psychiatrist reiterated “it’s not possible. Side effects [like this]—that doesn’t happen”. The doctor diagnosed her with a delusional disorder. Her medical records state: “Firm fixed delusional belief about medications causing side effects… Impression: delusional disorder with significant health anxiety and OCD with comorbid depressive symptoms.” Rosie was then committed against her will to a psychiatric facility and forced to take medication for her “delusions”. Four years later, Rosie still suffers the same symptoms.

Although her doctors were ignorant, the problems Rosie suffered are actually well-known amongst patient advocacy groups. Rxisk.org, a drug safety compendium founded by psychiatrist David Healy, explains: “Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD) is an iatrogenic condition in which sexual function does not return to normal after the discontinuation of serotonin reuptake inhibiting antidepressants… Most people who take an SSRI, SNRI, or related medication, will feel some degree of genital numbing, often within 30 minutes of taking the first dose. In PSSD, this genital numbing and other sexual side effects remain or do not resolve completely when the drug is stopped… Non-sexual symptoms that may accompany PSSD include emotional numbing, sensory problems, and cognitive impairment… It has been suggested that based on the available data, PSSD may be quite common.” Although sexual dysfunction is labeled as a “side effect”, numerous patients report issues far persisting withdrawal. The term “drug injury” is more appropriate here.

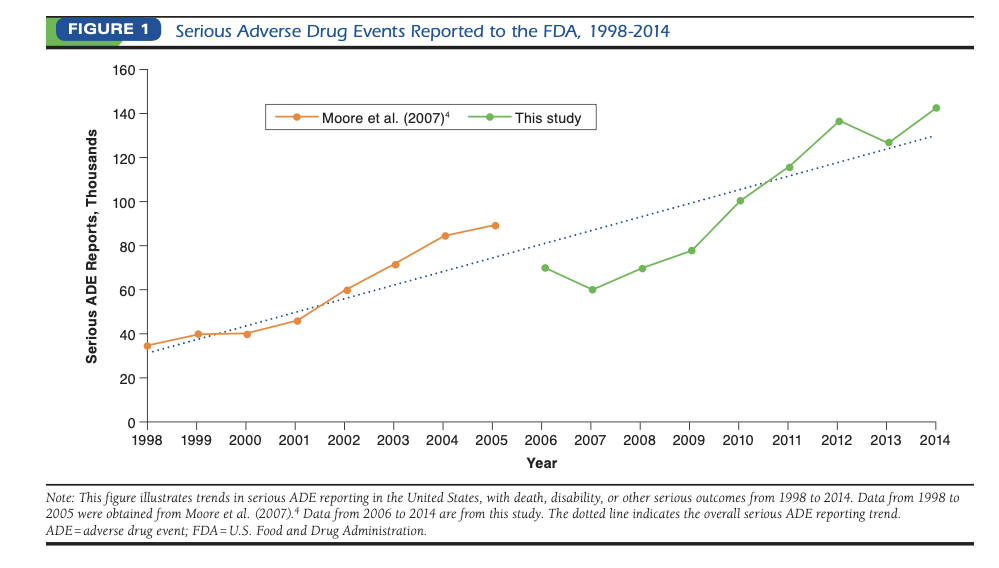

Drug Injuries are a piece of a wider problem known as iatrogenesis (doctor-made illness). Although drug injuries are virtually absent from public discourse, available research considers them a leading health risk. A 2018 paper examined FDA data on adverse drug events (ADEs) and found a rate of over 100,000 serious injuries per year. That rate has been increasing rapidly: “From 2006 to 2014, the number of serious ADEs reported to the FDA increased 2-fold… A previously published study… found that from 1998 to 2005, there was a 2.6-fold increase in the reports of serious ADEs and a 2.7-fold increase in the reports of fatal ADEs”. It seems that the rate of serious drug injury is doubling per decade. Moreover, the study grouped ADEs into categories of severity and determined the top 10 contributors for each. The “death” category contained one psychiatric drug. The “disability” category contained four—three of which were SSRIs, the class of medication that injured Rosie.

For most of my life, I knew nothing about this problem. I had some vague awareness that patients occasionally had a “bad reaction” to a pill, but I assumed that these reactions were one in a million and it never crossed my mind that something like permanent genital numbness could occur. I only came to understand it when it happened to me personally. I don’t feel comfortable telling my whole story right now, but the outline parallels Rosie’s. I had a mental health episode and was prescribed ostensibly “mild” medication. I developed anhedonia and mild akathisia which persists nine years later. After my injury, I suffered severe health anxiety which was diagnosed as “obsessive compulsive disorder” (OCD). I started panicking about things like “how much water am I drinking” and “does my apartment have a secret mold infestation”—things that I had never previously considered threats. My therapist was baffled, but for me the cause was quite obvious. After medicine had betrayed me so badly, I became terrified that I couldn’t trust anything to keep me safe. Like Rosie, I became so distressed that my father had me involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital.

I spent a long time in OCD therapy and learned a lot about the field. I really believed in it for a while, but I have a very negative opinion now. I find the field’s thinking quite frustrating because it omits any discussion of iatrogenesis. This ignorance is particularly troubling because OCD patients are heavily medicated (often with doses surpassing the FDA recommended maximum) and are therefore at an elevated risk of injury. While in treatment, I met five OCD patients who suffered this ordeal—severe “health anxiety” following an iatrogenic injury; and numerous others who I suspect had such an injury. One developed tinnitus after an SSRI and was worried that the noise would ruin his life. Another suffered memory problems after withdrawing from an SSRI, provoking constant panic about failing to recall details of her day. Three all underwent ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) and developed daily distress over reported cognitive impairment.

As far I am aware, there is zero mention of iatrogenesis in the OCD literature. Not only have I never met an OCD therapist who believes in PSSD, I have never met an OCD therapist who has heard of PSSD. In fact, OCD patients are encouraged to view reluctance towards medication as “obsessive anxiety” and are recommended “exposure therapy”. This entails playing at taking medication (holding medication in hand, taking a vitamin instead of medication etc.) in order to desensitize to the “irrational” fear that medication might be harmful. This is the advice I got from my therapist (a published expert in the field). I described how my health anxiety started after a drug injury. He said “maybe the best exposure would be to ask your psychiatrist for ‘the dirtiest med’ [his exact words], the one with the most side effects and the worst evidence-base, and take that as an exposure to overcome your fear”.

An acknowledgment of the OCD community’s awkward reticence motivates two research questions: 1) How often do OCD patients develop an iatrogenic injury resulting from psychiatric treatment? 2) How often do patients develop “health anxiety” only subsequent to an iatrogenic injury? My hypothesis is that the rates for both are substantial. Moreover, I hypothesize that the absence of such questions from OCD literature is not an academic accident, but rather the effect of an institutionalized ignorance.

How Did Medicine Go Blind?

In his book Pharmageddon, David Healy writes: “Drug-induced injuries are now the fourth leading cause of death in hospital settings. They are possibly the greatest single source of disability in the developed world… If we turn to the evidence base to care for and ideally cure this new disorder afflicting us, we find there is none—no guidelines, no studies, but instead close to a blanket dismissal of any evidence that things could be going wrong”.

Healy notes that this “blanket dismissal” is a recent development. “Good medical care once firmly embraced the idea that every remedy was a potential poison that inevitably produced side effects—the trick lay in knowing how and to whom to administer this poison… [But] in the era of evidence-based medicine, the marketing barrage of the pharmaceutical companies and the promise of statistical significance have led doctors into a world in which they regard treatments more as fertilizers or vitamins that can only do good if applied widely”. I believe this has been a ubiquitous experience for the victims of psychiatric iatrogenesis: assuming that you are ingesting a vitamin, only to later realize that you have been ingesting a poison.

I interpret this eerie ignorance as a kind of false seeing; a reconfiguration of Foucault’s “medical gaze”, thus inspiring the name “the iatrogenic gaze”. In its violence against the patient, this gaze has both a positive and a negative task. The positive task is to misinterpret human suffering (particularly madness) as medical illness in need of prescription. The negative task is to dissimulate any injury caused by these prescriptions, misinterpreting it as a new symptom of the original diagnosis.

Foucault described his philosophical method as an “archaeology”. This entails collecting a bulk of historical records in order to trace the origins of a concept; but in clarifying the origins, he also hoped to destabilize the concept, showing it to be contingent and dubious—or at least showing that something worthwhile in an old style of thinking had been forgotten. I would like to explore the iatrogenic gaze with an abbreviated attempt at such an archaeology. I will focus on the two aforementioned works: Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic and Healy’s Pharmageddon. Both examine changes in medical theory (Foucault studies French medicine from 1750 to 1850, Healy studies American medicine throughout the 20th century) and challenge the assumption that such changes are unequivocally progressive.

Let’s start by clarifying Foucault’s concept of “the medical gaze”. Foucault rebukes the common perspective that modern medicine arose simply out of scientific objectivity. Rather than characterizing premodern medicine as “superstitious” and modern medicine as “objective”, Foucault suggests that the eras employed two different conceptual frameworks: what he calls “the botanical model” and “the anatomo-clinical model”. The botanical model entailed visiting a patient’s home and classifying his story into a thematic species (similar to how a botanist classifies plants). The anatomo-clinical model entailed admitting a patient to a clinic and interpreting disease as aberration in a particular part of the body (relying heavily on autopsy for research and confirmation of such aberrations). The change altered the very way a doctor “sees”. When examining a patient, a doctor has an overwhelming amount of information presented to him. Inevitably, he will have to focus on some information and ignore other information. Therefore, when the doctor “sees” the patient, he is selectively looking for predetermined concepts. He sees with a language. The vocabulary of signs, symptoms, and diagnoses forms “a theoretical grid”. He gazes through this grid and matches diagnoses only to pre-established options. This process of seeing through a grid is what Foucault means by “the medical gaze” and he was fascinated by how greatly a new grid could change medical practice.

Foucault concedes that the anatomo-clinical grid is preferable, but reminds us that it also carries limitations: “That which is not on the scale of the gaze falls outside the domain of possible knowledge. Hence the rejection of a number of scientific techniques that were nonetheless used by doctors in earlier years. Bichat even refused to use the microscope… Still more significant is the rejection of chemistry… In eighteenth-century medicine… when one wanted to know what inflammatory fever consisted of, one carried out blood analyses… At the beginning of the nineteenth century, this experimental apparatus disappeared, and the only remaining technical problem was to know whether the opening up of the corpse of the patient affected by inflammatory fever would or would not reveal visible alterations”. Medicine became so fixated on autopsy that microscopy and blood sampling were strangely rejected.

Healy describes a similar change by contrasting two influential American doctors: Alfred Worcester and Richard Cabot. Worcester represents the old style of doctor-patient relationship and intuitive care. Cabot represents the new style of biological analysis and scientific rigor. Ideally, there would be a synthesis: a patient-first medicine outsourcing to high-tech interventions only when necessary; but the opposite seemed to occur. Not only did Cabot’s scientific austerity win out, but it degenerated into a parody of itself. Doctors became hypnotized by the appearance of “science”, even if the literature they consulted was essentially pharmaceutical advertising. They prescribed medications which were useless if not harmful, for conditions that debatably even existed. When medications did cause harm, the doctors were completely blind to it. We can understand this change as a new medical gaze and use Healy’s extensive research as grounds for an archaeology.

The early 20th century saw “[the] astonishing development of truly novel and extremely effective agents, from the antibiotics and cortisone to the diuretics, antihypertensives, hypoglycemics, and psychotropic drugs, as well as the first chemotherapy for cancer. It seemed [medicine was] set on a course in which genuine developments would succeed each other for years to come”. Such optimism would be disappointed by dwindling pharmaceutical progress in the later half of the century. Nevertheless, the optimistic attitude became second nature and doctors viewed new drugs, even ones barely outperforming placebo, with the same exuberance with which they viewed penicillin. Early success in a field is often misinterpreted as a generalized template for future science, ignoring limitations of the research. Antibiotics and insulin were genuine scientific breakthroughs. However, a culture developed which viewed pharmaceuticals as inherently revolutionary and assumed future research could only provide more breakthroughs. Doctors developed an automatic disbelief of emergent findings showing new pharmaceuticals to have limited benefits and substantial risks.

Pharmaceutical disappointment was more easily acknowledged by industry executives who realized that dwindling progress would undermine profits. Industry pivoted to a focus on regulatory capture—hijacking the academic process to promote dubious new drugs. This move “transformed pharmaceutical outfits into companies who market drugs rather than companies who manufacture drugs for the market.” A crucial factor enabling the change was the delegation of drug safety testing, formerly conducted by impartial public sector academics, to the private sector. We see the emergence of “Clinical Research Organizations” (CROs) which deliver clinical testing as a service. A lack of oversight allows the CROs to massage trial data in favor of industry objectives.

Healy writes: “Where once a professor might have analyzed the data from a trial, now personnel from the CRO collect the records from each center and assemble them back at base. The events in a patient’s medical records or the results of investigations are then coded under agreed-upon headings from dictionaries listing side effects… If later asked at an academic meeting what happened to patients on the drug, this is what they will cite. In this way the blind lead the blind—giving a whole new meaning to the idea of a double-blind study. For instance, academics presenting the results of clinical trials of Paxil for depression or anxiety in children wrote about or showed slides containing rates of emotional lability on Paxil and placebo. The presentations were relatively glib, and there is no record of any member of any audience being concerned by higher rates of emotional lability on Paxil, probably because none of those involved realized that emotional lability is a coding term that covers suicidality; in fact, had they had the raw records in front of them clinicians would have realized there was a statistically significant increase in rates of suicidal acts following commencement of treatment with Paxil.”

Control over clinical trials allows the pharmaceutical industry to formulate medical guidelines opportunistically. Although guidelines are established by independent committees, they often use only the glib summaries that industry provides. The presentation of strategic summaries can exploitatively bend guidelines so their recommendation conveniently endorses the prescription of the newest drug that industry is trying to market. The guidelines thus formed shape how doctors are trained and how they practice. There can even be a legal dimension in which a doctor is held culpable if he contravenes a guideline. As such, the guidelines reconfigure the medical gaze. They become its language—its theoretical grid. Doctors see only the illnesses listed in guidelines and become blind to the treatment risks that aren’t mentioned in the guidelines. I once spoke to a psychiatrist about PSSD and he agreed to watch a video about it. The next time I saw him, he shook his head glumly and said “I’m studying for recertification and there’s nothing about PSSD in our training”.

Guidelines are all the more powerful in a medical culture that has become increasingly standardized. The medicine of Worcester’s time was more “botanical”, focusing on a patient’s story and only outsourcing to biological testing when investigating an hypothesis. The modern era is instead inundated with routine testing. We have measurements of blood pressure and weight, blood tests for sugars and cholesterol, imaging such as bone scans and mammograms, and psychiatric screenings for depression and anxiety—just to name a handful. Healy laments the tendency of doctors to rigidly follow guidelines for these tests, often recommending unnecessary treatments just to get the numbers right.

Conversely, overreliance on testing blinds doctors to problems which are not currently testable. Psychiatric iatrogenesis is neurological and neuroscience is in its infancy. Traumatic brain injury is easily recognizable on an MRI, but most neurological damage (even most concussions) lacks reliable biomarkers. When a patient develops genital numbness there is no way to examine his nervous system and confirm the damage. The new gaze can only see with empirical testing and, as Foucault understood, “that which is not on the scale of the gaze falls outside the domain of possible knowledge”. If a patient starts an antidepressant and immediately develops genital numbness, Worcester would see an obvious drug injury; but the standardized doctor, lacking any testing protocol for genital numbness, is blind.

But how does this blindness spread outside of the medical field? In The Birth of the Clinic, Foucault is not only interested in the academic changes accompanying a new medicine, but also the cultural changes it fosters. The impetus to reform medicine was catalyzed by the French revolution. Its culture despised entrenched traditionalism, particularly that of the Catholic church. The revolutionaries suggested that government funding once provisioned to the church should be reallocated to medical practice, thus creating a modernized religion. The culture was enchanted by “the myth of a nationalized medical profession, organized like the clergy, and invested, at the level of man’s bodily health, with powers similar to those exercised by the clergy over men’s souls”; We see the construction of the “doctor-magistrate… In addition to his role as a technician of medicine, [the doctor] would play an economic role in the distribution of help, and a moral, quasi-judicial role in its attribution; he would become ‘the guardian of public morals and public health alike’”. The iatrogenic gaze is then internalized as a pseudo-religious practice. Hyper-medicalized man scrutinizes himself for deviance from medical guidelines in the same sense that Christianized man scrutinizes himself for deviance from Church doctrine. We are all mini-psychiatrists now, self-screening for depression and anxiety, ready and eager to follow the prescription guidelines; and, as psychiatrists, it never crosses our minds that these guidelines might be harmful.

Drug Injuries Are Hidden Behind “Health Anxiety”

Now we can understand the iatrogenic gaze as forming from outdated pharmaceutical optimism, predatory publication mechanisms, and early neuroscientific ignorance. We can also see how this gaze is made ubiquitous by its transformation into a public morality. This gaze has a catastrophic effect on psychiatric practice. Common drug injuries are inevitably misinterpreted as psychiatric illness. For the modern psychiatrist, Healy observes: “it is depression that gives rise to suicidality in patients on antidepressants, not the drugs… it is schizophrenia that gives rise to a disfiguring neurological condition, tardive dyskinesia, rather than treatment with antipsychotics”. Ex-patients lament the frustrating contradiction in which, despite having numerous friends who were harmed by psych meds, any doctor they speak to simply responds “I’ve never seen that before”; but from a Foucauldian perspective, the doctor’s ignorance makes perfect sense. The doctor, examining his patient only through his theoretical grid, genuinely cannot “see” PSSD because he doesn’t have a word for it. In the narrow language of hospital codes, his best translation is “health anxiety”.

And here we reach a troubling question. Is “health anxiety” just a rhetorical trick to hide iatrogenesis? I do not wish to make the argument that all (or even most) cases of health anxiety are actually iatrogenic injuries. People have always worried about their health and will always worry about their health. Rather, I suspect that “health anxiety”, as a diagnosis, has a secondary usage. It is too uncomfortable for our medicine-worshiping culture to admit that its proud institution might actually be harmful. The “health anxiety” diagnosis therefore allows us to avert this painful truth by misattributing it to a psychiatric disorder.

In his essay Mental Illness and Psychology, Foucault writes: “Our society does not wish to recognize itself in the ill individual whom it rejects or locks up; as it diagnoses the illness, it excludes the patient. The analyses of our psychologists and sociologists, which turn the patient into a deviant and which seek the origin of the morbid in the abnormal, are, therefore, above all a projection of cultural themes”. He then references the Freudian concept of “infantile regression” (the tendency for the madman to resume childlike behavior).

Foucault believed this concept is faulty because it ignores its cultural background—namely, the construction of an institutionalized education system. “If regression to childhood is manifested in neuroses, it is so merely as an effect… The whole development of contemporary education, with its irreproachable aim of preserving the child from adult conflicts, accentuates the distance that separates, for a man, his life as a child and his life as an adult. That is to say, by sparing the child conflicts, it exposes him to a major conflict, to the contradiction between his childhood and his real life… Neuroses of regression do not reveal the neurotic nature of childhood, but they denounce the archaizing [infantilizing] character of the institutions concerned with childhood”.

For Foucault, infantile regression is not an innate characteristic of madness; rather, it is a stylized expression of madness stemming from a culture whose education system has become infantilizing. The education system has become an artificial incubation chamber in which a child is sequestered from outside life. It is only because of this institutional bubble that “childhood-mode” is considered a refuge to return to in times of despair. As the psychiatric concept of “infantile regression” ignores this context, it serves to mask the failures of the education system.

Similarly, we can understand the psychiatric concept of “health-anxiety” as a mask for the failures of the medical field. Medicine harms us physically by promoting dangerous treatments. It harms us mentally by converting health-care into an overbearing morality. In many cases, this is the obvious cause of a patient’s distress. Yet, the medical field can never acknowledge this because doing so would mar its reputation. Perhaps Healy’s most damning criticism is his characterization of the modern provider as a “factor doctor”. “Doctors increasingly resemble the employees of the occupational health department of a factory that in the course of business exposes its workers to disability-inducing aerosols. These are doctors who are all too aware that their ongoing employment depends first on keeping mum about problems the workers may be having and second on being willing to recommend laying off workers at the first signs of any ill health—having persuaded them that they aren’t fit for the job rather than conceding that job conditions might be the problem.”

In a similar sense, the psychiatrist persuades Rosie that her illness is causing delusions about medication, rather than conceding that medication might be causing her illness. I do not mean that providers are intentionally covering-up iatrogenesis (although this does sometimes happen). I believe that the OCD providers I met with were well-meaning, albeit quite naive. Instead, I suspect that the masking happens on a subconscious and paradigmatic level. To acknowledge iatrogenesis, the doctor must first entertain iatrogenesis as an hypothesis. He must consider the possibility that he has caused harm and that psychiatry causes harm somewhat often. Such a theory is unsettling, so it is typically ignored (perhaps in the same way that we ignore red flags in an otherwise attractive romantic partner).

My guess is that this avoidance forms a negative feedback loop, particularly in academia. Researchers don’t consider iatrogenesis, so there is no research on iatrogenesis, which makes future researchers even less likely to consider iatrogenesis. Instead, they research “health anxiety”. I believe that this negative feedback loop, founded in a squeamishness around iatrogenesis, is the primary reason for the omission of iatrogenesis from the OCD literature. Until the OCD community comes to acknowledge the extent to which the medical gaze has become iatrogenic, they will fail to understand their patients and often proceed to harm them further; and until the medical gaze learns to turn inward and see its own pathologies, we will continue to suffer its violence.

This gaze you are talking about – this theoretical grid we impose on reality: you are very close to an insight that is available only to perception, and which is destroyed when you approach it through philosophies of others or by your own theoretical activity which is again STILL THE THEORETICAL GRID. So you’re clearly a very intelligent man – take you’re theoretical specs off for just a moment and see with me. And we will see if seeing beats all Western philosophy, being the Mother of all true insight in every cultural tradition in the world. The rest, theoretical speculation, is mere intellectual posturing, mere egoistic bullshit. Why? Because it has no relation to the understanding of reality at all, obviously, but in exersizing the socially conditioned intellect, making it more clever at spinning out bullshit that has nothing to do with the only human actual that ever was, which is AWARENESS AND THE VARIOUS HAPPENINGS IN AWARENESS. Thought was the effect of social conditioning by language and social forms and social experience, OBVIOUSLY. It arises from the memory of social experience which conditions all our thought forms, all our thinking, while the processes involved with thinking, like reason, obviously was learned in the social millue in the natural art of discussion.

The terminal problem with Foucault’s theory of the ‘medical gaze’ is that it fetishizes a particular variety of a universal problem which is the social conditioning of our brains which conditions and produces the intellect which circumscribes and directs and distorts perception of what actually is, as it is, so we should dispense with Foucault, take off our theoretical specs, and actually have the balls to see what is as it is ourselves and examine therethrough the general, actual problem. Come on – don’t be shy. I know I’m a mad man but that’s why I’m no longer socially conditioned and therefore shy. Perception NEVER defines what is, and never says anything at all, so can never be ‘wrong’. It just shows what is as it is, and any attempt to DEFINE this ‘what is’ is the conversion of the actual perception into a socially conditioned representation which we call language and knowledge, which we mobilize as thought. Now, isn’t this a fact for you? You see, I have not arrived at any of this through theoretical speculation, but basically through what the socially conditioned intellect describes as a psychosis. This socially conditioned intellect is the means by which each organism, each subsequent generation is strapped to and harnessed by the social process, which conditions all their thought, thinking activity, all their socially conditioned activities, so it is not an individual at all but the social process pretending to be me so it can basically control the whole f*cking organism and shape it’s life.

Now I’ve had a psychosis, but drug addiction or criminality or other such extreme alienations from the social millue can produce the same effect as the ‘psychosis’ (sic) had on me, which is to liberate me from the tendency to adjust to the social millue which for me eventually lead to becoming free of the socially conditioned mind altogether. My consciousness is free to see, uninfluenced, and undistorted by concepts, and the result is insight into what actually is, as it is, which is only ever consciousness. No coscious human being can ever get outside of consciousness – no conscious life can. We can speculate it, we can make theories about it, we can posit conceptually this thing called the ‘outside world’, but the underlying phenomena we refer to is what we call sensation, not the world, and sensation is a happening in consciousness we conceptualize as the world. How did I come to see all this? Is it theoretical speculation or philosophizing? It’s simply seeing what actually is as it is. It is what the East calls meditation, and similar insight into what I see is generated by the Eastern meditative or philosophical tradition, but the person who I see is 100% describing the reality I see is this person called Jiddu Krishnamurti, who is one of the most renouned spiritual teachers of all time. He failed all his exams at school, was not accepted at any University obviously, but was being groomed for this role called ‘World Teacher’ by the Theosophical society – you can read up on the story. But in the end, AFTER disbanding any association with this role as world teacher, and any association with the Theosophical society, he actually did become the most renouned and respected speaker and writer on the problem of human life, human conflict, what we call consciousness, and what we mean by religion. And the Dalai Lama and probably almost all prominant Buddhists and many of the other reverred teachers of the time like Ramana Maharshi and Sri Ananda Maya, recognized him as ‘the world teacher’ and ‘the guru of gurus’ respectively. Yet he couldn’t pass a single exam.

Now, that wasn’t theoretical speculation but uninfluenced, unconditioned observation of life as it is that got him there. So do you see what the Western philosophical tradition is missing? ACTUALITY ITSELF. Theory and concepts are socially conditioned and socially regulated and sanctioned representations of insight gained from perception, but we have the raw fire, the Mother of all knowledge itself, available to us always as perception. It was observing and understanding the phenomena you call ‘psychosis’, and observing the dysfunctional and fictituous computer program in the head called ‘me’ that gave me the insight into all of this, and we should how so many philosophers of the Western tradition right from the ancient Greeks have come upon their insights while withdrawing into solitude, away from the demands of the social millue which inevitably trigger the socially conditioned thinking and life activities that obscure and mask simple perception of what is, for example Hereclitus, Plato I think and probably many others, Nietzsche who wrote all his most prminant works in solitude, Marx whose writing really started to take off withdrawing from the social millue after his wife gave birth, which is hardly a socially conditioned activity but Mother Nature herself, and the whole Dada explosion emerged out of the phenomenal and insightful writings of Tristen Tzara – and you can actually see many of the fundamental insights of the Eastern tradition, into the destructive and artificial nature of thought, social processes and conditioned assumptions and everything else, but in a radical, anarchistic and explosive form that couldn’t be more distant to the profound expositions from the Eastern ‘philosophical’ (better meditative) traditions.

But I don’t advocate exploring the Eastern traditions except for interest or leisure. Start to realize, allow your brain to discover and realize actually, that PERCEPTION is the God’s eye of ALL philosophy, not the intellect, and the basic destruction of the great philosophy of the post-Enlightenment period was precisely this sprawling mass of socially conditioned thinking that emerged post-reformation for obvious and well documented historical reasons.

Sorry – I have a super brain but no self: I’m just allot of empty tubes and they blow vigorously when stressed and spew out endlessly and uncontrolably. Am I talking to my plumber? No I’m writing a comment. Oops – sorry about that matey. We should have a bear some time. I live in England and bear is soon going to be introduced by the national health service so we can cope the old fashioned way because the country is a disease that flowered, a disease process that flowered and enslaved humanity and destroyed the Earth and all our children’s future. Oops – I hope you’re not English like me. If so it doesn’t matter anyway because our brains are as good as chopped liver over here innit mate.

Report comment

Interesting, and thought provoking blog, Alex. Thank you, I may go pull out that old Foucault book on my bookshelf, that I likely read long ago for some philosophy or religion class.

But wow, No One, there is so much more research for me, and no doubt all of us, to do. Thank goodness for the real internet, although we must hope and pray these days, that the truth is not erased from it.

It is bizarre that my dreams are set up like the internet, with lots of websites. But isn’t it even more bizarre that two of my supposed nicknames – within the internet of my dreams – are a ‘No One,’ and a ‘No One Else,’ websites? It’s good to be a perpetual learner and researcher … in one’s waking hours … and when one is dreaming “the impossible dream.”

We likely are good friends within our dreams, No One.

Report comment

Someone Else really is a name I could have also chosen for myself! So feel free to become No-One or Zero any time, if you would grant me permission to ocassionally be someone else.

And it certainly IS bizarre that your dreams are set up like the internet, with lots of websites! I have no idea what you mean really, but I’m jellous nonetheless. I really don’t think I have any dreams any more, which is probably related to the total atrophy of my socially conditioned mind (happy accident).

Anyways, have a nice day Someone Else anonymous like No-One is (by the way, I think I’m called ‘Whoever the person’ on my YouTube account but don’t worry, I won’t copyright or patent the handle!)

Report comment

Permission granted, Google finally figured out who I am, and took my right to use that pseudonym away on YouTube. Gosh, does a lady who found the medical proof of the iatrogenic etiologies of the “sacred symbol of psychiatry” / the “cash cow” of big Pharma/psychiatry, deserve to have a right to use a pseudonym? One would think so … for safety reasons … but not according to the God complexed Google.

Well, I don’t know much about my dreams, but the internet of my dreams supposedly started when I was very young, and my family moved from Chicago to NY. I was sad to have to move away from my friends, so I supposedly created Annie, Eric, and Lisa websites in my dreams, so that I could stay friends with my IL friends in my dreams.

I started kindergarten in NY, and just started adding more websites in my dreams … each friend having their own website.

My family moved to OH when I was in junior high, and our church had a mission statement to “go get everyone with love and the word of God.” My subconscious self decided to accept this challenge. I kept adding more websites of new friends, I supposedly befriended the actors via the TV, and the musicians via the radio.

I also supposedly adopted a bunch of nicknames for myself, like Someone Else, Something Else, No One Else, etc. and Everyone Else … since getting everyone else was the goal in my dreams. I also had other websites, like a P.I.G. (standing for pretty, intelligent girl) website, where a lot of the male chauvinist pigs got put.

The internet of my dreams is basically a way to classify all those I’d met, or supposedly befriended, in my life and dreams. My subconscious self supposedly became somewhat of a “Dream Weaver.”

It’s a long and interesting story that goes on, and I can tell it largely in the lyrics of music, as if “he’s killing me softly with his song, singing my life with his words.” It’s largely a love story, except the psychology/psychiatry crap … “all dreams are psychosis” ??? No, all dream, and that’s normal … even for us “beautiful dreamers.”

Hopefully that’s enough for you to get the gist of how the internet of my dreams works … “the rest is still unwritten.”

But like many around me, I am “living the dream” (and formerly was living the nightmare of psychology/psychiatry).

But mine is a dream about how we are all going to save ourselves from the societal mess, in which we find ourselves. So it is a hope and love filled dream. Keep the faith, pray to God.

Report comment

This is an exceptionally interesting and I hope you don’t mind me saying so, for me really funny exposition. “I also supposedly adopted a bunch of nicknames for myself, like Someone Else, Something Else, No One Else, etc. and Everyone Else …” Haha! I can relate. And I think the ‘me’ IS other people – I really do. We are seeing, feeling, being things. The me is just thought and it’s other people in disguise, basically! That is a gross simplification but it is an enormous onion that I’d otherwise have to peel and there ain’t no room for it on this website, even though it’s Mad in America! Thanks for your story. Certainly your psychological struggles have turned you into a very interesting person, so that’s a definite win!

Report comment

“… In this world, it’s just us …” And we’ve got to try to turn those DSM deluded lemons into lemonade, right?

Report comment

Excellent article. However, I don’t think there’s a cure for willful ignorance.

Here’s my take on the situation: pharma marketing has taken scientific hubris to a whole new level and not much will change until enough people learn how much they’re being taken advantage of by pharmaceutical industry AND psychiatry. After all, that’s what with the tobacco industry.

Report comment

Cases of iatrogenesis will keep increasing until the public starts demanding more accountability from their prescribers.

Report comment

I feel for Rosie.

Report comment

The article presents a compelling argument, although it inaccurately posits that “providers are (not) intentionally covering up iatrogenesis,” and proposes that “masking happens on a subconscious and paradigmatic level.” This assertion is flawed as it suggests that providers are not cognizant of the harm they cause, whereas, in reality, they are aware but indifferent to the consequences.

Report comment

“Subconscious” is not synonymous with “unintentional.” It just means you’re not willing to acknowledge those intentions. Most “professionals” ARE covering up intentionally, even if it is not something they are consciously aware of doing. Any time someone gets defensive when presented with contrary evidence, they are intending to cover up.

Report comment

According to my medical records, some doctors do intentionally utilize psychiatric iatrogenesis, to cover up their partner’s easily recognized iatrogenesis.

And a similar thing happened to a loved one, so covering up medical errors with psychiatric iatrogenesis is not likely uncommon.

And let’s be realistic, all doctors are taught in med school about anticholinergic toxidrome … so they all know the antidepressants and antipsychotics, which are both anticholinergic drugs, are dangerous neurotoxins.

Report comment

In his book,

“THE DIVIDED MIND

The Epidemic of MindBody Disorders'”

John E. Sarno, M.D., tells of how he developed GERD after his wife had taken him away on vacation. He frankly admits that his interpretation of this was that his subconscious “rage” and being forced to leave off his work for the interim – pre-Net and cell phone days, I believe – had caused the symptoms.

The fact that any single drug such as Lexapro can cause such a vast spectrum of VERY REAL symptoms/responses to develop, and the fact that withdrawals, too, can bring about or trigger SUCH an immense variety of adverse effects, both physical and emotional/psychic, suggests to me that SUGGESTION by our unconscious minds plays roles we may necessarily struggle to identify, characterize, differentiate and quantify…or which, hopefully, we may hopefully simply avoid altogether by treating “depression” not as some mysterious group of diseases or disorders which cause hopelessness….but AS hopelessness, itself.

We can then, hopefully lovingly, attempt to ascertain what, if any, subconscious factors may be contributing, and whether such physical problems as, oh, poverty, stress, burnout, exhaustion, Vit. B12, magnesium or other nutrient deficiencies may be involved, or anemias or toxoplasmosis or Lyme disease or brucellosis or thyroid issues or neoplasia or parasites or ANYTHING other than “clinical depression!”

Mind you, once we allow our kids to be taught some “mindfulness” or that they are NOT their minds, we may be well on our ways to hopefully and lovingly overcoming our epidemics of angst and of pharmaceutical poisonings – just as Good Old Nature has hopefully lovingly been intending for us to do all along!?

Thank you VERY much for another very stimulating essay, all concerned!

Tom.

Report comment

Health Anxiety…maybe it is HealthCare Anxiety.

Report comment

You got that right.

Report comment

Big Pharma may be unreliable at best, but mind that you don’t fall prey to Big Placebo in the process. Any way you slice it, the “alternative and complementary medicine” types aren’t offering their cures to you just to be kind- they’re every bit as greedy and corrupt and simply don’t have the opportunities to mislead you as their more entrenched counterparts. Given half a chance, they’d just be the new Big Pharma and do everything exactly the same as what we have now.

Report comment

Dear Anonymous, we may take a jaundiced view of life and of all the activities of our fellow humans. Or we may take a rose tinted view. Or both.

But I, for one, believe that we can also learn to remove the very lenses through which we view things and see those lenses for what they are to a growing degree.

We can choose to clean and polish them or to exchange them for new ones – once we can discern what is out conditioning and what is not.

If we take a superficial look at our own past motives, we may see fear and greed operate a lot, and, naturally, view others’ actions in similar light.

If we hold our nerve and look more deeply, however, I believe we can always see that what we were striving for was actually happiness, and that it was actually fear, in the form of haste or otherwise, which always forced us to act ignobly.

When we look for heroic altruism in others, I believe we can find it all around us, too.

True healing Is see as a two-way process, both parties being healed in the transaction.

I believe that all those who understand and realize this find themselves delighted to freely give of their gifts, freely making use of the placebo effect.

In the process, of course, there is always the risk that one may allow oneself to neglect one’s own needs to such an extent that ones burns out severely, as I believe there is reason to believe Jesus did.

Every good wish.

Tom.

Report comment

I have no other option than death after severe iatrogenic injury from an SSRI.

Last thing i can do is spreading my posts everywhere so my voice is still visible when i’m dead.

So called ‘health’care has my blood on their hands.

I never received any informed consent. I was bombed with terms like ‘health anxiety’ ‘personality disorder’ and other garbage diagnosis after i was injured while i never had a mental illness to begin with. I was prescribed the drug for some simple life stressors.

Spread the word, since i can’t anymore.

People are dying.

Thank you.

Report comment

Tremendous post, JB

Thank you.

When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose.

Immense suffering can make for immense mastery, and unlimited courage and conviction.

I don’t believe it is actually possible to takes one’s own or another’s life, no matter what.

Of course, there is murder and suicide, but who knows how many worlds we may each inhabit at any instant.

I don’t know that the boys had the foggiest idea of the truth of their lines

“You u can check out any time you like

But you can never leave.”

If I take my life, what is left? I..or Me. Or Life. Or the I-AMness. Or Being. Or that which has always animated your body, and witnessed your every thought, word and deed your own immortal self.

I spent most of my first 49 years wishing I had never been born, and 11+ of them being drugged horribly.

But Cheerfulness, Light always finds the way to break through – once we have been cracked and broken open enough. And it found me, too:

https://youtu.be/9Hefh6OeSzs?si=-HyI3hF8865Uz9zw

If ever you’d like to correspond or chat, please contact me any time at [email protected]

Peace!

And THANK YOU, JB!

Tom.

Report comment

The ‘Iatrogenic Gaze’ is for those who like feeding off other’s emotional traumas.

Report comment

I don’t know…….I couldn’t quite get through the whole article, having experienced so much of the iatrogenesis. I get internally all riled up. No more emotional numbing is nice. Thankfully, I really am doing okay now, years later…. after coming off my last drugs and leaving psychiatrists behind.

Anyway only commenting as I kept thinking that “Iatrogenic Glaze” might be a better title. How glazed over they often are when we talk of our truths and experiences!

Thanks for writing and teasing it all out. Some really good points on how it all gets classed into the anxiety and OCD now, then further and higher drugging, and round and round they keep going. And oof, it hurts just reading about it all. Keep writing though. Get it to those with prescription pads(I’m not sure it’s being taught as yet, drug harms).

We need to keep being heard, not hurt anymore!

Report comment