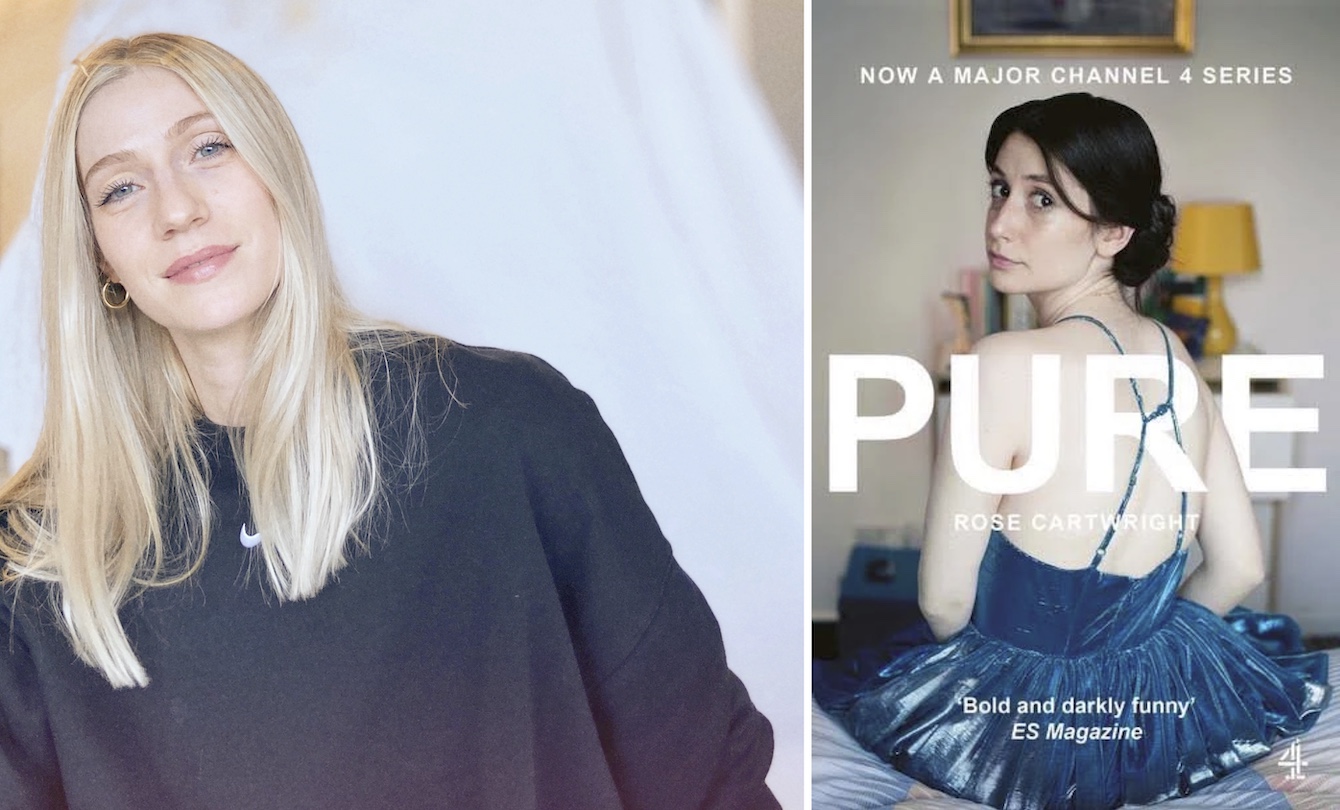

Rose Cartwright is a screenwriter and the author of Pure, a hugely successful memoir which was then turned into a series for Channel Four. She is also a writer and producer on Netflix’s 3 Body Problem. Pure portrayed Rose’s autobiographical account of finding that she had OCD, a “mental illness”, and the breakthrough that this medical framework provided her. This was short-lived. In her new book The Maps We Carry, she writes about the dawning realization that the “illness” story she had believed in and publicly advocated for, was wretchedly incomplete and often dangerous.

In this interview, Cartwright charts her journey of painful and lonely disillusionment with the “mental illness” framework. She talks about understanding the place of her own childhood trauma and also the limitations of simplistic trauma narratives. She speaks about the place of psychedelics and meditation in helping her uncover her disconnection, eventually to realize the importance of trusting relationships and communities. In this brutally honest book and interview, Cartwright reflects on the importance of holding all our understandings around mental health and suffering, lightly.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Ayurdhi Dhar: You wrote ‘Pure’ about your experience with intrusive thoughts and the diagnosis of OCD. It was then turned into TV show. At that point you were a huge advocate of the medical model of understanding human suffering. But things shifted — you write that you were confronted with information and experiences that challenged this understanding. First, could you tell us briefly about your struggle with intrusive thoughts?

Rose Cartwright: Around 15, I started experiencing vivid and graphic intrusive thoughts of a sexual, violent, and harm-related nature. These images started coming into my mind almost nonstop, hundreds of times a day, and they were profoundly terrifying and shameful. Their content was deeply disturbing and I didn’t tell anybody because I was ashamed. This continued into my 20s.

There were other problems that went alongside the intrusive thoughts; there was self-harm, bulimia, lots of control behaviors, a great deal of anxiety, and suicidal ideation. I was in a really difficult place. I was searching for answers. I didn’t understand my experiences and I was lost. I started to Google intrusive thoughts to find if there were people experiencing the same thing as me. I found that intrusive thoughts are a common symptom reported by people with OCD. I started reading about obsessive compulsive disorder, and it seemed to fit so, so well. I learned what I was doing was compulsive behavior.

It all seemed to make a great deal of sense. Alongside these revelations came a medical framing of the whole experience. So, not only did I now have language — ‘obsessions’ and ‘compulsions’, but also a psychiatric diagnosis and a whole set of assumptions as well — OCD is something that is experienced by hundreds of thousands of people around the world, which it certainly is, but also that this is a brain-based problem, that it can be explained by theories of neurocircuitry and serotonin imbalance, and that targeted medications and therapies can help with those symptoms. The whole framework was illness.

I bought into it and in Pure, I wrote about the experience of intrusive thoughts and internal compulsions, and that resonated with people. But what I was also promoting was this medical way of seeing my problems, that my OCD had arisen spontaneously when I was a teenager – completely decontextualized, like the symptoms of a cold. It’s a story that didn’t serve me for very long.

Dhar: That makes sense. We are provided with a meaningful framework that gives us language, a causal explanation for why this is happening, and also some hope for alleviation of suffering. You say that you used this medical framing but eventually began to rethink this understanding of human distress. What happened that made you go – “Wait, this is not serving me. Maybe I don’t buy into it anymore”?

Cartwright: There was a series of catalysts. It was an intellectual and an emotional shift. The most blatant thing was realizing that I wasn’t getting better. The diagnostic model had provided relief but it had been temporary. Discovering other people with OCD had felt like a life raft but in the long run my problems kept returning. How I characterized it at the time is I kept on relapsing, this illness kept on coming back. There was a sense that “I’m not sure that the model that I’ve bought into is getting to the heart of what’s wrong for me”. But I repressed a lot of those doubts. There wasn’t anybody in my circle who was questioning this.

Another catalyst was an intellectual one. I went to Trinity College Dublin to interview a neuroscientist called Dr. Claire Gillan, a brilliant professor. She explained to me that OCD isn’t a biological reality. That was a very difficult thing to hear because my identity was built around the idea that OCD is a biological phenomenon where the brain is distinct from people who’ve got depression or anorexia.

She’s not saying that OCD isn’t happening at the level of the brain, of course it is. When my OCD was at its worst, if you looked at my brain, you would have seen neural correlates. What she was saying is that there aren’t biomarkers that distinguish DSM diagnoses — that was news to me! I thought the DSM was based on biological data. I realized that I was mistaken about a lot of my assumptions about what we know about mental health. We know much less about the brain than a lot of people in the mental health advocacy space realize.

Dhar: Yes, people have this idea that if it’s not biological, the pain can’t be serious or real. Tell me about this experience of disillusionment, from diagnosis being a huge part of your identity, and it happens to many that they become attached to it and molded by it, and then to have the scales fall off your eyes.

Cartwright: It was a lonely one because I spent several years becoming very bedded in as an OCD advocate, and that community is founded on assumptions with a very biomedical worldview. There wasn’t much space for another way of seeing the problem of obsessions and compulsions.

Dhar: Eventually you found the trauma model that talked about extreme childhood stress events, and it explained a lot of your suffering. Tell us about what you found helpful about this view that your OCD was partly caused by early childhood stress.

Cartwright: When I started doing high dose psychedelics, what emerged from those experiences was a crystal-clear realization that had always been lurking in my peripheral vision — that my severe mental health problems were influenced by the fact that my mom was severely depressed throughout my childhood, had been given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and was repeatedly being admitted into psychiatric hospitals. At home there was a constant level of ambient chaos. I saw a lot of distressing things when I was very young and into my 20s. It makes sense that that a young psyche would go to extreme lengths to manage the stress.

Dhar: You also write that there are certain problems if we adhere to the trauma model too rigidly, which is a focus on this singular lens of trauma. Sometimes looking only at trauma can be a barrier in seeing the role systemic factors to play in our distress. Could you talk about the issues with using the trauma model rigidly?

Cartwright: Sometimes the trauma model can be too focused on single issues. It can hold a magnifying glass over childhood relationships, as important and influential as they are, without looking at the broader context in which those relationships are nested. My mom’s distress was impacted by everything going on around her. My dad was out of work; I was raised on benefits and there was a huge amount of financial stress. The school system was very poor, my brother had a lot of behavioral and learning difficulties, and he was not being supported.

In one sense you could say that my distress was caused by having a difficult relationship with mom as a result of her illness, but in another sense, you could say that my distress is actually reactive to a much broader set of social, national, even international stressors. The trauma model can be slightly limiting if it turns our parents or our caregivers into pawns, in simplistic psychological stories, in simplistic ideas of cause and effect, because it’s never simple.

Dhar: Your first experience with an altered state of consciousness was spontaneous and not psychedelic induced. Let’s get into that story.

Cartwright: Around the same time as this shift was happening in how I saw mental health, I got into Vipassana meditation. I was desperately looking for answers. My OCD had relapsed. I couldn’t believe I was back at square one after a book and a TV show that told my redemption story. It was unbearable. I wanted to explore meditation. I dived in at the deep end and went on a 10-day silent meditation retreat in California.

The retreat hosted by Josh Goldstein. The first three days were hell on earth. When you’ve got intrusive thoughts hundreds of times a day, sitting with those thoughts is a very challenging thing to do. On day three, something very interesting happened. I started to have an experience of altered state. I had never taken psychedelics, but I had a two-hour long experience of a non-duality, white lights, feeling like the boundaries of my body were eroding and blending with the cosmos, a sense of overwhelming love, a sort of an impersonal love that extended to all beings. My mind was absolutely blown by this!

It was the first time in 15 years that I had been liberated from intrusive thoughts.

It also didn’t fit with my understanding of mental health problems at the time, that I had a disease. In the wake of this experience, I thought (A) what the hell was that? I hadn’t taken any drugs. I didn’t know that those kinds of states were possible. (B) if I’ve got a disease how can the symptoms just spontaneously subside for a couple of hours and then return?

Dhar: That’s where psychedelics enter right? What has been your experience with psychedelics? What have they offered you?

Cartwright: I started reading and there is a lot of overlap between the brains of experienced meditators and the brains of people who are post high dose psychedelics. I started speaking to psychedelic healers, neuroscientists, and psychedelic researchers about what was going on during the psychedelic experience. Why is it so strange, mystical?

I’d kind of glimpsed behind the curtain at a version of existence that was possible beyond the misery that I’d been locked in for 15 years. I wondered if there might be other routes into that place. I decided to take the plunge and do a high dose of psilocybin (magic mushrooms) in Amsterdam with guides. It was that trip which blew the doors off the medical model. In that trip, I watched my mom, the essence of my mother, get sucked into a giant black hole in the sky. I was just sobbing and begging her not to leave me, not to leave me here alone with this pain. I came away realizing that that was pain that had been lurking under the surface of my experience since I was a little kid.

Dhar: That sounds terrifying and painful. I have had a similarly educative but terrifying experience.

Rose: Educations are like that. It was a profoundly terrifying but valuable experience.

Dhar: I want to talk about people’s expectations. You write about how people go into therapeutic psychedelic experiences with expectations that “I will find my trauma”. Afterwards they might cling too tightly to a story and it becomes this rigid fixed identity, just like a mental disorder diagnosis. You write this is also problematic. What’s a good state of mind for someone to enter a therapeutic psychedelic experience with?

Cartwright: Often the framing of psychedelic experiences is that you’re going in to explore your trauma, feel all the pain that you repressed when you were a little kid, release that pain, and come out feeling better. It can be simplistic. Psychedelic experiences tend to surprise you. It’s a good idea to let go of any assumptions of what you’re going to find, and really surrender to the unknown and to uncertainty.

I wrote about the Zen Buddhist concept of Shoshin, a beginner’s mind, trying to let go of any preconceptions and expectations of an end results. It’s important both in terms of going into an experience and in terms of integrating experiences afterwards. If you go in with the expectation that everything that comes up is to be interpreted literally, you can run into problems because some of these experiences are extremely esoteric, often very metaphorical. You might have something that feels like a memory but perhaps isn’t. It’s very difficult to navigate if you’re trying to arrive at an objective truth about what’s happened to you.

Hold conclusions with love but lightly. Use any conclusions that you come to about your psychedelic experience until they are helpful, but don’t let them calcify and become part of your identity. You don’t want to walk around like a traumatized person. You want to be reborn in each moment. That’s the whole Buddhist philosophy.

Dhar: That was my favorite part, the gentleness. You write that you worry about how psychedelics are getting co-opted by pharmaceutical industries. Tell us more.

Cartwright: I do an exercise in my book where I speculate that if psychedelic therapy been available to my mother when she was at her worst, would it have been helpful? She was spending months at a time in bed, sobbing at the dinner table, crying at night — catatonic, unable to experience her life, let alone enjoy it. It could have been helpful to a certain extent. But after the trip she would still have come back to the stress of trying to feed a family of six on low income and benefits. She would still have been isolated. My dad would still have been out of work.

My concern with the medicalization and industrialization of psychedelics, and these very profound experiences being turned into protocols and interventions, is that they don’t actually address the social determinants of distress that lead to a huge amount of trauma in the first place.

Dhar: One of the final realizations in your book seemed to be that psychedelics were important, but it was eventually about community, people, relationality. Something about community helped as you had your main psychedelic experience with others, right? What did you find about the place of others in this whole process of healing?

Cartwright: One way to conceptualize how those experiences were healing to me is the way they changed my brain. Another way is I was able to re-experience and let go of repressed emotion related to my traumatic past.

Another way to think about it is that I went into those experiences, and was able to, because I worked with guides and in a group. I was able to fully let down my defenses in front of other human beings for the first time. Afterwards I was able to sit and be extremely vulnerable with people who cared, could be relied upon, and who would be there for me in the following weeks.

Where the healing comes from, that’s a really complex question, but I think that last part is as important as the rest.

Any psychiatric or psychological intervention counts for nothing unless we’re held in trusting, loving relationships. What beats under every mental health problem is that we want to feel safe and loved. Unfortunately, the way that we live gets in the way of that core need.

One of the things that came up in these psychedelic experiences was loneliness — there’s no one coming, and there’s no one that I can reach out to. I think that was a hearkening back to real desolation I felt as a kid. My mental health is dramatically better right now and I put it largely down to psychedelics but in another way, psychedelics opened up another wound in that the loneliness. It’s appropriate to be lonely in the world that we live in right now, and psychedelics don’t solve any of the conditions of modern life that contribute to our loneliness — the fact that we live in a consumer society, are atomized from those we love, from other generations, the fact that we don’t live in community.

The next layer is dealing with that existential loneliness and treating it with tenderness, and not expecting it to go away. I don’t consider it a mental health problem to feel lonely when I live in London.

Psychiatrist Bruce Perry talks about relational poverty — a lot of people in the West, we have a huge amount of privilege and political stability compared to a lot of the world but we paid a really high price for our financial stability. Where we used to have strong communities, we now have strong markets, and I think most of us have just normalized isolation. Psychedelics can lead one to become disillusioned with modern life, and that can be difficult.

Dhar: Thank you. Let’s change gears. More than a year ago, Joanna Moncrieff and her colleagues published a huge umbrella review that dealt a final blow to the serotonin theory of depression. Many psychiatric experts scoffed saying “well, of course, we’ve known about this for decades”. You write that there is a huge gap between this expert reaction to the article and that of the actual public. Please speak about that.

Cartwright: I encountered dismissiveness along the lines of “of course, no one believes in the serotonin theory of depression anymore. Why are you even talking about this stuff? You’re just knocking down a straw man.” I sat there thinking, hang on a second, you guys in your ivory towers might have figured out the nuances, but these simple stories were disseminated by the psychiatric industry for decades because they were profitable. The vast majority of the public still buy into them and into the products of that industry.

The psychiatric community claims to have moved on to a biopsychosocial approach, but the story that is out there among most people on the street, is that depression is caused by a spontaneous malfunction in their brain. How can the psych professionals can be so dismissive of ideas that people who went before them put out into the world. I think it’s their responsibility to provide the corrective.

We know very little about the brain, but we do know that the brain reacts to the environment, and that people’s emotional health reacts to environmental conditions. I think there’s a duty of care that is not being done.

\

Dhar: I reported on an international psychiatric conference in India which took a public health approach. For three days, we talked about structural determinants of mental health (poverty, discrimination, violence etc.); it was amazing. But there was no conversation about treatments or interventions. When I asked about it, they went back to “antidepressants have shown promise”. I wanted to pull my hair out. So, let’s shove a pill down this farmer’s throat whose distress is caused by climate change, exploitative money lenders, pro-corporation policies, where he can’t feed himself and his family. This trending conversation around structural determinants doesn’t translate to practice when it comes to interventions.

Cartwright: I think you’re absolutely right. Part of the problem is that medicine has a very important but quite small role to play for the most seriously mentally unwell. The structural and policy changes we’re talking about, it’s not a doctor’s job. Well, there’s social prescribing — the doctor basically gives you a directive to join a social club or a sports team. But you don’t need a medical degree to do that. We’ve always known how to live in community.

Dhar: My last question is a comment. This is the pattern I found in the book — you wrote about the biomedical model, the trauma model, use of psychedelic therapy, and relationality, and at every point you also talked about the limitations. For example, everything reduced to personal trauma might limit a person’s ability to see larger systems, or the way psychedelics can be co-opted. There is a very thoughtful and nuanced take around these topics. How did you reach this careful, tentative, and complex understanding?

Cartwright: My meditation practice has been very instrumental. Meditating is not just about feeling better. It’s also about learning how to think and realizing how we get attached to our thoughts and ideas, and then they become part of our identity. One thing my Buddhist teachers do is they tread very softly with ideas. They encourage you to think critically about your own assumptions; if something feels really true and solid, just stay with that and see if it changes.

One thing that characterizes the harmful practices in psychiatry and psychology is an imposition of a simple story rather than a facilitation of self-inquiry. You go to the doctor and you’re offered a simple solution. I didn’t want to contribute to that.

I see the same thing in trauma narratives — everything that you feel is about your relationship with your dad or mom, and none of this is sufficient. What is helpful to me is to foster a cognitive flexibility — cultivate uncertainty because I’m guilty of being dogmatic in the past. I don’t want to make the same mistakes again.

***

MIA Reports are supported by a grant from Open Excellence, and by donations from MIA readers. To donate, visit: https://www.madinamerica.com/

Thanks for this. I have been waiting for clarity for folks who got pulled in to the pill solution and label fix.

And I think an almost fractal quantum theory is needed for who all of in this earth are treading water at best. Somewhere I heard someone say these financial and political titans are just barely treading water. We are all in the very small boat on rough and choppy waters. I hope that there is so form or chain of support for all species on this planet that will allow a new perspective on life as it is.

Report comment

Great interview.

Psychiatry’s medical model (systemic gaslighting) with its toxic “medications” did much more lasting emotional, psychological and physical harm to me than any childhood trauma ever did. So called “mental illness” has more to do with experiencing chronically dysfunctional/abusive relationships and/or systems than malfunctioning neurotransmitters. But I don’t doubt that psychedelics are capable of dislodging painful memories that get stuck in hard-to-reach areas of the brain/unconscious.

Report comment

Treading softly with ideas seems alien to a troubling number of psychotherapists as most seem hellbent on espousing their preferred brand of trauma dogma.

But psychiatry’s not much different as most practitioners seem delighted singing the praises of their latest psychiatric “meds”.

So what’s the easy, no-cost solution: mediate to shut out their collective psychobabble.

Report comment

Rose does an excellent job describing the psychological inflexibility characteristic of the majority of people who work in the “mental health” system, most of whom on some level seem threatened by individuals who advocate a more holistic approach, as if what is suggested is somehow sacrilegious, not realizing their own intellectual rigidity stands in the way of psychological creativity, which very often is all that’s needed to germinate a person’s emotional healing.

Report comment

They turned stuttering into a biological problem too. The truth is that most of the time it has to do with anxiety and fears.

Report comment

Sabrina, I can’t say for sure how many times I went over your above comment – twice, at least, though – reading “stuttering” as “suffering.”

Haste? Stupidy? Dementia, either drug-induced and/or other? Because of all the insults, injuries, infections, information and far-from innocuous environmental poisons and radiations inflicted on my poor old brains these past decades?

Who knows? Not I. All I know is that I must believe I must trust that all my mistakes must represent my best work to date, at least – if I am to gain/regain the most clarity fastest.

See, I think we will all soon look back to the old paradigms of human suffering – first, dare I say it, at least in the West, largely thanks to an ancient Judaic and then Judeo-Pauline or Sinfulness-based approach, and largely thanks to an ?equally Judeo-Pauline and now Judeo-Pauline-Neuroscientific- and Judeo-Pauline-Psychiatric perspective – as hopelessly missing the mark (and, ironically, “hamartia,” a Greek term used in the Judeo-Pauline New Testament for “Sin” is borrowed, I believe, from the Greek archery term for missing the mark…) – missing the point that Suffering/Sinfulness/Mental Disorder/Personality Illness is all about a loss of one’s sense of humor – or, rather, about a misplacement of it, at least.

Perhaps stuttering has been a seeming obstacle for you, Sabrina – even if it has not been one to propel you, too, to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20500 – yet?

Perhaps all suffering, any obstacle, anything which provokes (internal) resistance (to what already clearly already IS!), be it the embarrassment and awkwardness of stuttering or anything else, is only provided us, individually tailored or custom-made to best suit our needs, to propel us through it or over it and to the Enlightenment which surely dwells on the other side of it?

If indeed the attainment of Enlightenment/Spiritual Consciousness/Salvation/Metanoia/Repentance/Transformation of Consciousness/The-Kingdom of God/of the (formless) Heavens/of the Father/Liberation/Zen/Self-realization/Individuation – and, with it, the recovery of our sense of humour and of a growing delight in finding ourselves in our own skins – is indeed what psycho pharmacologists – like various Scribes, Pharisees and Sadducees and the priests of various hues before them, all psychopomps manqués, or would-be ferrypersons of souls to Divine Bliss – sense is what they ought to be offering us and achieving with us, then, as we all grow to realize that one simply cannot possibly suffer too much, given one’s immortal nature, we can begin to address the missed underlying essential first principles with exponentially increasing enthusiasm, passion, inspiration, love, joy and….oh, yeah, HUMOR.

I have come to expect Christians to more frequently and more comfortably quote Paul or the Old Testament to me than the reported words of Jesus.

And I expect psychiatrists to refer to their old bibles, the DSM’s, or, at best, to a gravely (pun gifted if not intended) flawed, Puritanically-inspired neuroscience or to a psychology which denies the immortality of the psyche, necessarily ignoring the life and the life’s of Carl Jung and of the (pre-Judeo-Pauline) druids of my (Irish/Gaelic/Gallish/Celtic) part of the world:

“Caesar made similar observations:

With regard to their actual course of studies, the main object of all education is, in their opinion, to imbue their scholars with a firm belief in the indestructibility of the human soul, which, according to their belief, merely passes at death from one tenement to another; for by such doctrine alone, they say, which robs death of all its terrors, can the highest form of human courage be developed. Subsidiary to the teachings of this main principle, they hold various lectures and discussions on the stars and their movement, on the extent and geographical distribution of the earth, on the different branches of natural philosophy, and on many problems connected with religion.

— Julius Caesar, De Bello Gallico, VI, 14.”

– from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Druid

I love both your names, and their origins, btw, and thank you for a most stimulating comment!

Comfort and joy, and Happy 28th November, 2024!

Tom.

Report comment

Sorry, Sabrina (or Self, if I am once more just talking to myself): dementia struck yet again, and I wrote:

“…necessarily ignoring the life and the life’s of Carl Jung and of the (pre-Judeo-Pauline) druids…” above when I had intended to write

“…and the life’s work of Carl Jung…”

Sabrina/Self, I have come to try to welcome my mistakes as the workings of “God” or of Nature through me without my full consent, and so to accept that they must surely all represent “my” greatest works or contributions, to date.

I have also come to view any errors I spot as very deliberately and emphatically calling my attention to some gap/s I may choose to fill.

You know how human “problems” evolved to “issues” to “challenges” to “learning opportunities” or opportunities for growth?” Well, the more painful my growing pains prove, the more emphatically I may try to ensure they need not be repeated…that the gaps are filled, the omissions are made good:

It seems I need now to insert

ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=15pjQRA80bs

I reckon this excerpt alone from all of Jung’s work amply demonstrates why it was that neither Science nor Medicine nor Psychiatry nor Psychology nor Religion nor Philosophy, in general, has yet quite caught on to Carl – even if Eckhart Tolle has emulated and exceeded him.

Much love.

Many thanks.

Tom.

Now if a man tried to take his time on Earth

And prove before he died

What one man’s life could be worth

Well, I wonder what would happen to this world?

And if a woman, she used a lifeline

As something more than

Some man’s servant mother wife time

Well, I wonder what would happen to this world?”

– from “I Wonder What Would Happen to This World,” song by Harry Chapin, 1942-1981.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7qrbNygL0YU

Report comment

Carl Jung made interesting points about our subconscious mind.

Report comment

A brilliant interview. The inclusion of poverty, trauma, debunking the medical model and the self serving lies of psychiatry made it a wide ranging and thrilling interview.

Report comment

I find the OCD medical model interesting it is certainly big business. What I also find interesting is the minimal comment /research on the side effect of many of the psychotropics in actually inducing new OCD ritualistic behaviour. cariprazine for example induced ritual handwashing compulsion in my family member. 40 to 50 times per hour his fingers/knuckles completely debraided almost to the bone.

Report comment

Stimulants can also induce OCD behavior. It often leads to other diagnoses when folks have adverse reactions to stimulants. Especially Bipolar Disorder. It can be dead obvious what happened, but try to get them to quit giving the kid Ritalin and they freak out. Once had a kid I advocated for who had an eating disorder diagnosis. They gave her stimulants, and lo and behold, her appetite was reduced! They of course attributed it to a “relapse” in her “eating disorder” rather than realizing that stimulants were a bad idea for someone with that condition!

Report comment

“Intrusive thoughts” is an interesting or intriguing term, when you think about it, isn’t it?

CBT notwithstanding, while contemporary psycho pharmacology may not have progressed beyond a Cartesian misunderstanding that we think, therefore we are, that we are our minds, that there is no more to the psyche than our thoughts and emotions, we can nonetheless appreciate that that very thing which considers ANY thoughts to be intrusive can hardly be the very same thing that thinks thoughts, can’t we?

If we can successfully tell ourselves to calm down, to get a grip, not to take disturbing thoughts too seriously, to ask ourselves if there is ever any valid argument against trying to retain or to retrieve (more of) what passes for our sense of humor (or of “proportion”), who, on Earth is that “we” and who is or are the “ourselves?”

Eternity is a long time, especially in the middle.

Thank you for a great interview.

Tom.

Report comment

☯️☮️

Report comment

This is a wonderful article. I will be reading the book and I’m delighted to hear more positives about psychedelics And trauma. I’m surprised, though, as I was introduced to trauma as an individual and a collective experience.

The focus on relationality is probably the gem of the article and the book. Thanks so much to this mental health survivor who found healing in individual trauma and collective healing spaces.

Report comment

She was really really lucky to survive her psychiatric craze without much damage. Not everybody is that lucky. There are people who after these drugs are locked in constant akathisia or PSSD in whose a small dose of psychedelic causes a flare of iatrogenic damage or any insightful experience is blocked by PSSD emotional numbness. There is also no point in meditation when the mind is blank, devoid of any emotional content or spontaneous thoughts. Nothing to concentrate and internally observe.

I think she is still not aware how great of danger to her life she has escaped criticizing psychiatry only on a merit of not giving her improvement while finding it somewhere else. But not consider all the lethal damage the psychiatry may cause and end human life.

Report comment

I would include trauma in the social determinants of mental distress, rather than throw it out with the biomedical model.

Trauma is defined as the effect of social factors, which distinguishes it from the so-called “diseases”. This is why PTSD does not fit easily into the biomedical model and is not fully recognised by psychiatry.

Even “individual” childhood and developmental trauma always occurs in a context that is socially determined by factors such as parental isolation, lack of access to services, poverty, racism, intergenerational disadvantage etc.

Integrating our understanding of the effects of trauma with our understanding of the social factors that cause or contribute to trauma and psychological distress has seemed to be the obvious way forward for decades.

I agree that relational healing is probably one of the most important factors for trauma. But I don’t really get the jump from recognising the social determinants of psychological distress, to more drug treatment like psychedelics. Every decade or so psychiatry proposes a miracle chemical cure for harms which evidence overwhelmingly shows are socially and environmentally caused (or highly contributing) and therefore solvable, and chooses to kick the can of fixing them down the road.

If real attention, policy and action was addressed to social determinants and their effects, including trauma, the dominant psychiatric practices of diagnosis and medication would be mostly redundant. Support and healing could be better served by social workers and community support services, with therapy (or medication ) used only for temporary management of more serious effects of trauma and distress.

Report comment

I believe that Carl Jung explained as well as he could how any human being can help any other human being to find lasting peace, to heal, to realize that we are indeed already whole, and already more than fully equipped with all than any of us needs to survive eternities.

More recently, I believe Howard Schubiner and others have continued this work by making their own unique contributions, all of them supporting the understanding that if indeed there was a Jesus if Nazareth who healed many by eroding or undoing or blasting to oblivion their sense of shame, of “Sinfulness,” of unworthiness, and is that man predicted that anyone who believed in such work, understood it (and him) and wished to continue it, would indeed do “such works AND greater, too,”

“Which is easier to say – ‘Your “sins” are fore-given!’ or ‘Take up your pallet, and walk!’?!”

Or fly?

Thank you, Sabrina.

And Jesus and Howard and everyone of us

Tom.

Report comment

Who could have known unconditional love is healing? ; )

Report comment

Rose’s book helped me so much to not feel alone. I also have severe OCD. It was caused from being SA and all other forms of abuse in a romantic relationship. I cannot handle psychedlics but what has helped me more than anything has been facing the emotional pains and fears associated with OCD not just doing ERP without shadow work.

Anyway modern psychiatry has failed me time and time again for over 16 years. Inaccurate diagnosis, therapy of all kinds that led no where. Literal abuse and trying to destroy my brain. I did not let them.

I have also had bad experiences in the “spiritual” community as well. So be very careful in general who you try to confide in. $$$$$$$ and egoism is usually a huge factor in anyone “being there” for someone in the spiritual community. My advice – find people who want to love you for you. Difficult yes impossible no.

All I had to do was actually be honest and face the pain causing the OCD, the various pain and trauma cycles. Shadow work, love and understanding. Empathy and compassion. Start with self and then extend to others. I still have OCD but it takes time to heal on all human levels. Unconditional self love and self trust while also critically thinking has profound healing.

Report comment