Ihave a night life.

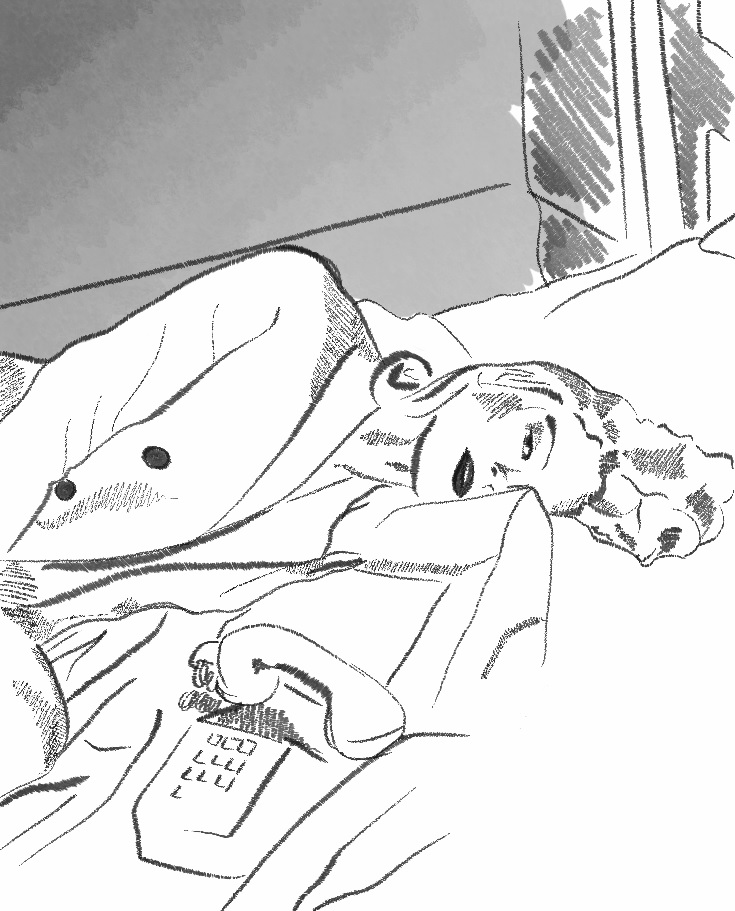

It started when I was thirteen—I would lie awake, buzzing, my eyes wide open while the world slept. Sometimes it’s accompanied by books. Sometimes by a relationship with a man who works different hours than me. Sometimes by the news that my father isn’t doing well.

Sometimes by dreams.

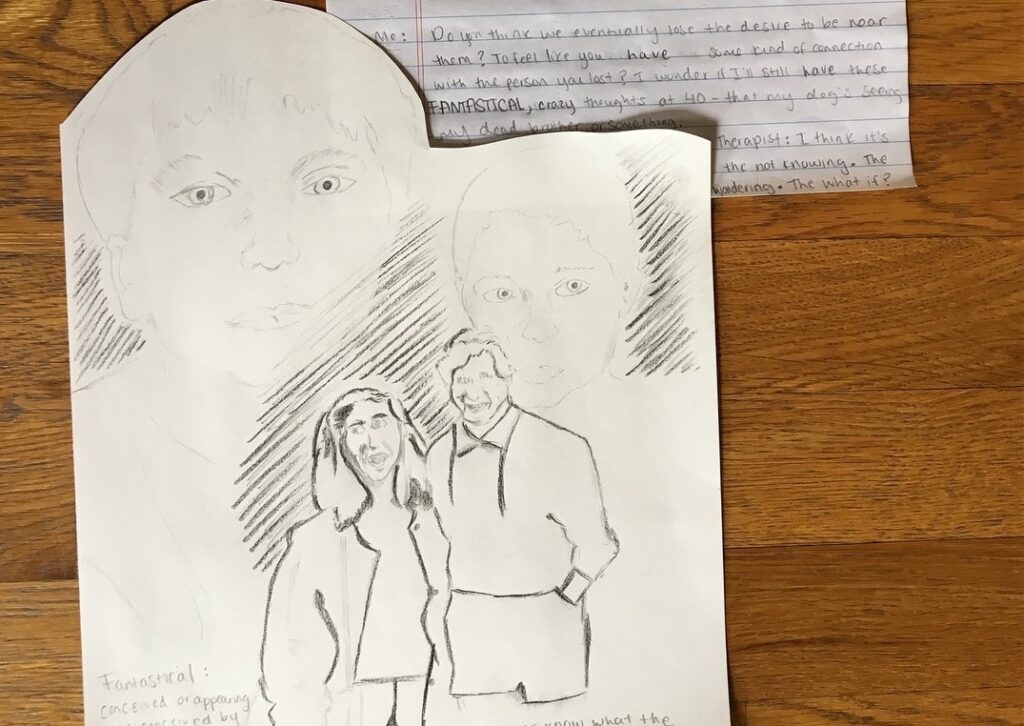

Dreams that the story I’ve been writing about the father and daughter now starts with the sentence: He is losing his mind.

Sometimes it’s accompanied by a friend across the world who knows I don’t sleep and stays in the chat just to keep me company. He’ll ask me if I got any sleep at all. I’ll say I did, a few hours.

Sometimes it’s accompanied by the dim lighting of a lamp or a single candle’s flame. Sometimes by a blue light. Most of the time, by a blue light.

Sometimes my dad keeps me company.

In the last six hours, I’ve called a hospital four times. I used to call the hospital when he was a doctor. Now I call because he’s a patient. I wanted him to accompany me on my drive to get coffee. He always accompanies me on my drives to get coffee. This morning, he had better things to do, he says. My eyes are going, he says. They’re forcing me to take medication I don’t want to take, he says. They don’t know what they’re doing. They don’t know what they’re doing.

Dad, it’s going to be okay, I say. Dad, you have delirium.

One of the symptoms of delirium is blurry vision. One of the other symptoms of delirium is terror. You are afraid because you have delirium, because you have an infection, because you have Crohn’s, because your disease went out of remission when you got hit in the face with a ball that stole your vision and disrupted your emotions, which led to stress, which led to stomach issues, which led us here—to this, the day when we all witnessed what we never thought possible: you lost your mind.

He is losing his mind.

And so am I.

At night time.

* * *

This isn’t the first time I’ve watched a man lose his mind.

The first time, I was ten. I became suddenly aware that my father’s behavior wasn’t normal. That slurring words and wetting beds wasn’t usual adult behavior.

I became more aware when he sat my brother and me down in the den and told us he was going to be gone for a while. A month, he said. You can visit, he promised.

I went once. It was a sterile mansion off a backroad we’d driven by dozens of times but I’d never noticed it before. Fifteen minutes from our house. He liked his roommate.

I remember a really tall man walking down a staircase in pajama pants. His eyes weren’t in the room with us. I remember feeling afraid of him.

I never visited again. My brother did, though. Every chance he got, he went.

A few years later, I saw it happen again. A jellybean caused it this time. One jellybean later, and my friend Emily was crying at school the next morning: I heard about your dad! Your dad! Your dad!

What was wrong with my dad? I thought.

Dr. A. called us this morning, your dad! He’s in the hospital, is he okay? Are you okay?

He’s always at the hospital. That’s where he works, it’s fine.

No, it’s not fine, he’s sick, Lexi. He almost died, he’s sick.

I watched him in the ICU, wires covering his body. He whispered to my brother: Take care of your mother and your sister. The odds of him living were 30%. I saw my mom sink to the ground and cry for the first time in my life.

A few years later, my grandpa stopped remembering details. First, it was the name of his street. Then the name of a fridge. Then my name. Then my dad’s. But he remembered his wife’s name until the day he died. He promised her he would.

Then it was my brother. The IQ of a genius didn’t help him with his addiction.

Then my dad again. Work was different. He wasn’t as sharp as the young guys, the ones who understood RVUs and computers and how to work them. I worked tirelessly to convince him he was afraid of nothing—that if he just started practicing, it would come easier. That didn’t stop him from buying a gun. Nor did it stop him from drinking again.

Later, my brother. But this time, permanently.

Then, my father. Two weeks in the hospital, emaciated, crying, screaming. Are you his wife? the nurse asked.

No, I’m his daughter. It’s my night to stay over. My mom and I are trading shifts.

Eventually it was a man I met at an art party in Austin. A year later, in the middle of the night at an Airbnb in Scotland, he sprang out of bed—darkness in his eyes—screaming, “Are they trying to kill me?” I watched him cower in the shadows in the corner of the room. “It’s just a dream, Raza. It’s just a dream. You’re having a nightmare. It’s not real. Come back to bed.”

Earlier this year, it was my dad again. On the roof of a garage.

Now in a medical psych ward. He’s suffering from delirium. It’s like nothing I’ve ever seen before. How can a man’s brain betray him so much it leaves him in a state of terror? Constant terror. They say it will take three days for him to get better, but I know my father. It will take longer. The lights aren’t off, they’re broken—flickering constantly.

Alexa, it’s my vision. You don’t understand. This is the last time you’ll hear from me, probably. I have to go. I have to go.

What is it about the fragility of the male mind? Why is it so quick to fall apart?

* * *

Night is coming.

I can feel it getting closer. It wonders how I’ll do tonight: Will I sleep? Will I stay awake? Did I follow all the steps?

Some nights, I don’t want to follow all the steps. There are so many of them, and my legs are heavy. My trunk feels tethered to the couch, and a lovely book is waiting to be read (The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath).

When I was little, books didn’t make me fall asleep. Just the opposite. I’d read and read and read. 2 am, 3 am, 4 am, and my father would be awake in thirty minutes. Just thirty more minutes and we’d go take a walk around the pond.

He’d tell me about his patients from the day before and turn me into the first of his day. But it wasn’t Western medicine he was prescribing. It was breathwork and meditation—guided meditation.

Breathe in and out.

Breathe, Alexa. Breathe.

Now sleep.

* * *

“No! No! No!” he screams, pounding his arms on the bed.

“No, don’t! Don’t! I can’t! No, no, no, no!”

I hear the nurse reply, “Jeff, you aren’t here as a physician. You are here as a patient. You aren’t performing a surgery. You are confused. Please le—”

“NO! NO! NO!”

From the deepest ache in my stomach, I blurt out, “Dad! Dad, it’s me. It’s Alexa.”

I hear him mumble, “Alexa?”

“Dad, I hear you. I hear you saying no. I hear you.”

He starts to form full sentences.

“Dad, I hear you saying no. Dad, what are you saying no to?”

“No! I can’t perform the surgery! Don’t give me that! I can’t perform the surgery, I don’t know how to do it, I don’t want to hurt anyone. Don’t give that to me, don’t give that to me! No!”

“Dad, I hear you. I hear you. Dad, breathe with me.”

He stops talking for a moment.

“Dad, breathe in…”

“NO! NO NO NO, ALEXA, NO.”

Like a thousand pounds of weight on my chest, I break.

If I can’t calm him down, who will?

It takes two nurses to restrain my six-foot-three, buff father. I remember a story—he was in the south side of Chicago with my mom. They were young. They took a wrong turn and ended up in a neighborhood they shouldn’t have been in–and sure enough, in the wrong place at the wrong time, a gang of men started to surround their car. Instead of driving away, my dad put the car in park and stepped out of the vehicle. “If we’re going to do this, let’s do this,” he said. He towered over them, then a solid 6 ft. 5—a man who almost went to the Olympics for swimming, he looked like the Hulk. His willingness confused them, and sure enough one by one they started backing up. He got back in the car and they drove away safely.

There has never been a point in my life where the feeling of his strength and that towering body of protection didn’t feel available to me. Where that man who woke up at 4:30 am to walk around the pond and tell me to breathe with him wasn’t available to me. Where that man who drove with me to get coffee, helped me get sober, helped me mend all my broken hearts, helped me, encouraged me, and loved me… wasn’t available to me.

The biggest before and after of our lives is the time when our parents are alive and the time after, when they’re gone. With every passing day, I can see the horizon of that line coming closer and closer. Behind it, a perpetual night awaits.

Breathe, Alexa. Breathe.

* * *

I publish a piece about sudden or extended death, and then I start to cry. Raza calls me immediately.

Hello? I say.

Are you okay? he asks.

I’m okay. Are you?

My dad just had a heart attack, he says.

Not two days prior, I’d spent half the day on the phone with his dad, an ear nose and throat physician and a psych NP.

Raza was boarding a flight home from India and couldn’t call him for me so he told me to call. And I did. It was the first time I’d heard his dad’s voice in two years.

“Tell me what is going on,” he said. “I will repeat everything back to you so you know I understand.”

So I told him. From my dad’s accident in May to the infection in June to the surgery in November to the suicide attempt in December to the psych ward in February. Trauma… after trauma… after trauma.

He repeats everything back: the Crohn’s, the incidents, the fears I’m having, and what the doctors are doing now. He tells me he’s familiar with all these issues, and that the sequence of events makes sense to him. Debilitating depression. No motivation to live. And a desire to die.

It makes sense, he says. It all makes sense.

I tell him what I’m doing from afar—how I’m going to go home, how I need to be there, how I don’t understand X and Y and Z and can’t they fix X and Y and do you know how long it will take for him to get better? Is he going to get better? Will you tell me that he is going to get better? He can hear my voice start to shake.

Breathe, Alexa. Breathe.

“It’s in times like these that we must hold onto hope.”