After surviving what he describes as mental health malpractice as a teenager, Locura en Argentina editor Alan Robinson found himself dubious about the psychiatric system’s ability to meaningfully help people in distress. “I always make myself question why things are this way, why the status quo is like it is,” he says.

Robinson’s focus was less on reforming specific problems within the system, like involuntary commitment, and more on an overarching issue. When it comes to psychiatry, Robinson explains, “I can say that there is one thing that should be changed all over the world”—this being the dominant grip the field has over the very meaning of reality itself.

“It’s very difficult for many people to imagine that we don’t live in only one reality,” Robinson says. “And it’s very difficult to think, for most people, that a hallucination is not a distorted truth… A hallucination, it’s a truth by itself.”

When people are told that the reality they experience is wrong or distorted, they lose the chance to express themselves and to see their experiences recognized by the world around them. What Robinson wanted, then, was to give people labeled as mentally ill the avenue for self-expression that they’re rarely granted.

Locura en Argentina wasn’t Robinson’s first attempt to do this. From spotlighting “mad” characters in his novels to running a publishing house for neurodivergent authors to publishing his own essays on mad studies, his professional endeavors all tend to stem from “this perspective that visions and voices, you shouldn’t avoid them. You should embrace them, take them with responsibility and care.”

It was Argentina’s history of human rights-based publications, which emerged in response to the country’s string of dictatorships in the 20th century, that inspired Robinson to eventually found Locura en Argentina in 2024. “In the 21st century, we don’t have dictatorships, but we have oppressive systems that transform people’s lives,” he says. Just as the earlier human rights publications gave voice to people being silenced by the government, Robinson hoped Locura en Argentina could spotlight the experiences of those being told that their basic perceptions of the world were flawed. (The site’s Spanish name actually means “Madness in Argentina.” This is because the Spanish word for “mad” is gendered—either “loco” or “loca” depending on who the word is applied to—while “locura” can be applied to anyone).

“Magazines like Locura en Argentina allow minorities that historically haven’t had access to express themselves to have a web magazine where they can express themselves,” he explains. “Not to fight, just to express.”

Through Locura en Argentina, Robinson aims to provide readers with a magazine that represents them and the “mad cultures” found in Argentina. “Madness is a language,” he explains. “You can communicate from madness, and you can express yourself from madness. And if you can communicate and you can express yourself with other people, you find that madness is not just a language but also a culture.”

Robinson believes that different “mad cultures” exist in different countries, and while Argentina’s history of immigration and resulting cultural diversity make him hesitant to characterize the country’s mad cultures in one particular way, there are a few forms of Argentinian “madness” that stand out. “It’s a country with a revolutionary spirit,” he says. “We’re not conformist people. And that’s something of madness—madness always will show a revolutionary spirit.” Robinson also sees madness represented in soccer, which inspires vehement passion in many Argentinians, as well as in the nation’s artistic culture. “We have a tradition of mad artists,” he says. “A lot of Van Goghs.”

Locura en Argentina centers itself around three main areas: culture, diversity, and lifestyle. Culture and lifestyle are both made up mainly of reviews, with culture including plays and books that represent mad cultures in Argentina, while lifestyle focuses more on events and destinations, such as restaurants, pubs, historical sites, and museums that are accessible for people with psychosocial differences.

Diversity, meanwhile, consists of various news stories, essays, interviews, reviews, and creative pieces that display a range of psychosocial experiences, portraying these as forms of diversity rather than illnesses or disorders. “We are for all kinds of human diversity,” Robinson says. “Gender diversity, cultural diversity, sexual diversity, and also psychosocial diversity.”

In addition, Locura en Argentina posts pieces published on other Latin American Mad in the World sites, including Spanish translations of work published by Mad in Brazil. “I’m interested in the Latin American perspective most of all,” Robinson explains, and he appreciates the unique outlooks these sites provide, such as Mad in Puerto Rico’s emphasis on decolonialism.

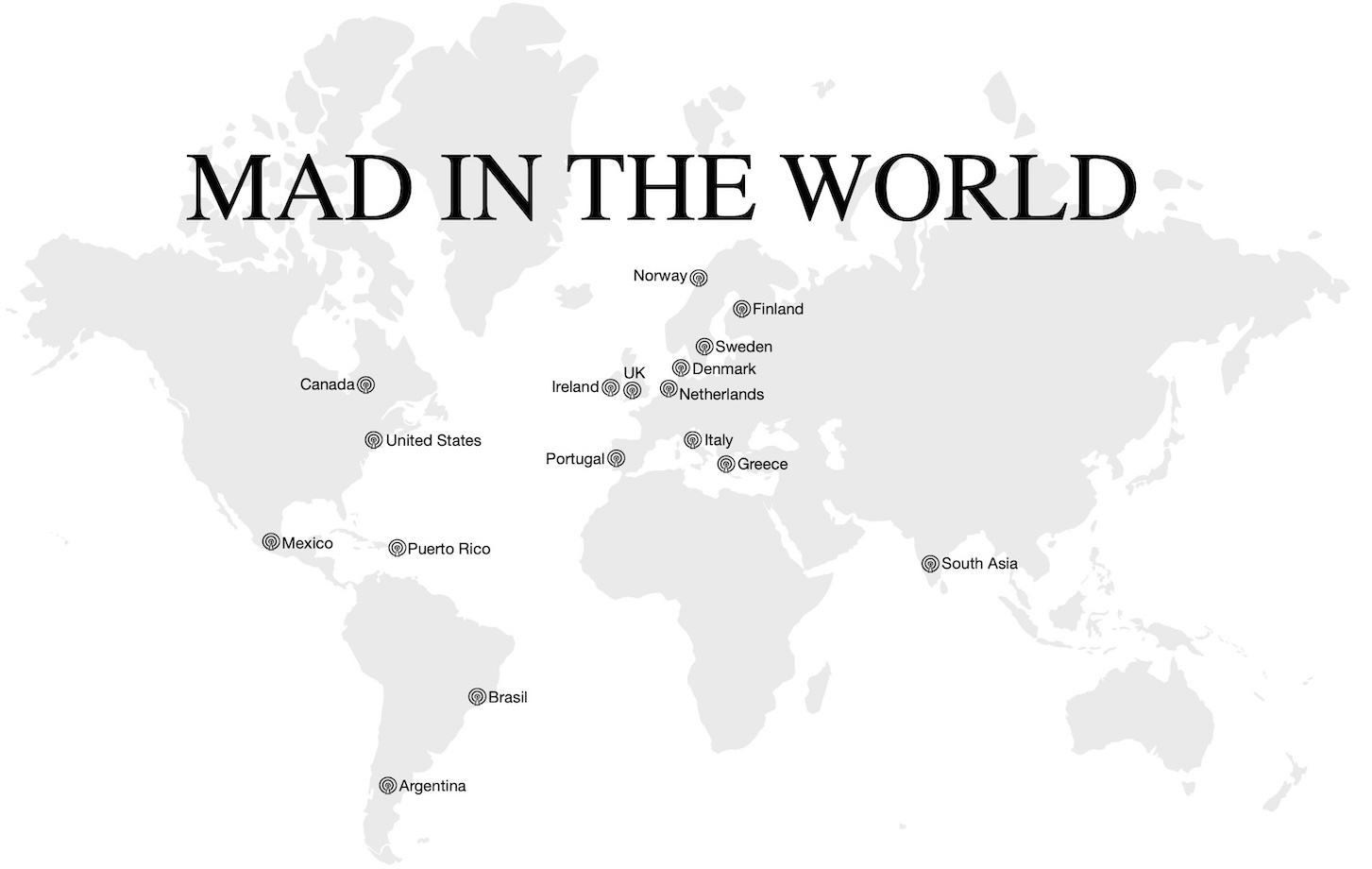

During its first year, Locura en Argentina has seen growth in both online readership and social media followings, especially from Buenos Aires, the capital city where Robinson himself is based. But Robinson says he’s less concerned with metrics and more with the site’s growing collaborations. In some ways, he’s pleased with the progress he’s seen so far in this area—for example, he’s excited that press agents have started offering Locura en Argentina free access to events or sending them free copies of books to review, which is essential for a site centered around reviews. Robinson also appreciates the connections he’s formed with other Mad in the World affiliates. “It’s always better to share with colleagues,” he says, and he finds the support gained from monthly meetings with the editors of other affiliate sites crucial for his mental health.

At the same time, though, these connections remind Robinson of just how difficult it is to manage a website like this in Argentina. “I see it in colleagues that it’s not the same to run a project in a country that has an economy like Argentina,” he says. As he explains, “I don’t believe we’re a ‘third world country,’ but we really are a country with an economy that’s not dominant… We’re kind of slaves to the economical power of the supposed ‘first world.’” This means that, while Robinson himself is able to edit the site without pay, most people in Argentina wouldn’t have time or be willing to work for free—and while Robinson would love to eventually have one editor responsible for each of Locura en Argentina’s three main areas, bringing on new staff members would likely require funding Locura en Argentina currently doesn’t have.

Robinson hopes to apply soon for funds to help finance this, but he adds that his focus right now is simply making sure the site survives through 2025. After all, as much as Locura en Argentina and other Argentinian human rights publications are cast as radical or controversial, Robinson knows the point of view they put forth is essential for many Argentinians. “It’s not radical,” he explains. “It’s just human rights. We just want to stand for people, power to the people.”

I thought MiA readers might find this synopsized history of pharma and medicine interesting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UM3jvS4pbm4

Report comment

I posted basically the same comment on Tucker Carlson’s youtube interview of an abused physician:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OeFtquLWFPQ

Since the physician mentioned Marcia Angell, I recommended Marcia’s 2005 book:

https://www.amazon.com/Truth-About-Drug-Companies-Deceive/dp/0375760946

That book recommendation is being censured by YouTube, at least it has been for the past hour plus.

Report comment

Thank you!

Report comment

Certainly the non-ordinary phenomena in what they call a psychosis is very well understood as a communication or a language, and we needn’t label ‘who from’ – it’s in one’s own consciousness, and is a communication, and conveys a certain vibration or tenor or emotion, just like ordinary language or artistic expression or in dreams and imaginings. If we understood this we would see the sanity of reading this book that is you’re mysterious consciousness, and once you start reading it you’ll never finish, because it goes on forever.

Report comment