A new philosophical article challenges the dominant psychiatric view that delusions stem from mental dysfunction. Instead, it argues for understanding delusions as adaptive strategies or purposeful responses to distress that have been misunderstood and pathologized by systems that exclude the perspectives of those experiencing them. In doing so, the article reveals how prevailing conceptions of mental illness may perpetuate epistemic injustice, marginalizing those most in need of recognition.

Delusions, which refer to beliefs about reality that are held despite being disproven by empirical evidence, are widely viewed as the result of a defect of the mind. But alternative perspectives consider delusions a coping strategy, or a movement toward the goal of reconciling “anomalous experiences” with routine life.

“The dysfunction approach has it that, ‘[W]hen someone is mad, it is because something has gone wrong inside of that person; something in the mind, or in the brain, is not working as it ought. Madness results from the breakdown of a well-ordered system; it is a defect or a dysfunction. It represents the failure of the system to achieve its natural end.’ The strategy approach on the other hand has it that, ‘[I]n the mad, we have a purpose being fulfilled, a movement toward a goal, a machine operating as it ought.’”

In a recent article published in the European Journal of Analytic Philosophy, Eleanor Palafox-Harris of the University of Birmingham uses the book Madness: A Philosophical Exploration by Justin Garson as a launching point to explore this tension between dysfunction and strategy.

If you have ever been seriously confronted with someone who invents their own reality and acts to defend it, you would be more than happy for a “mental health professional” to take that person off your hands.

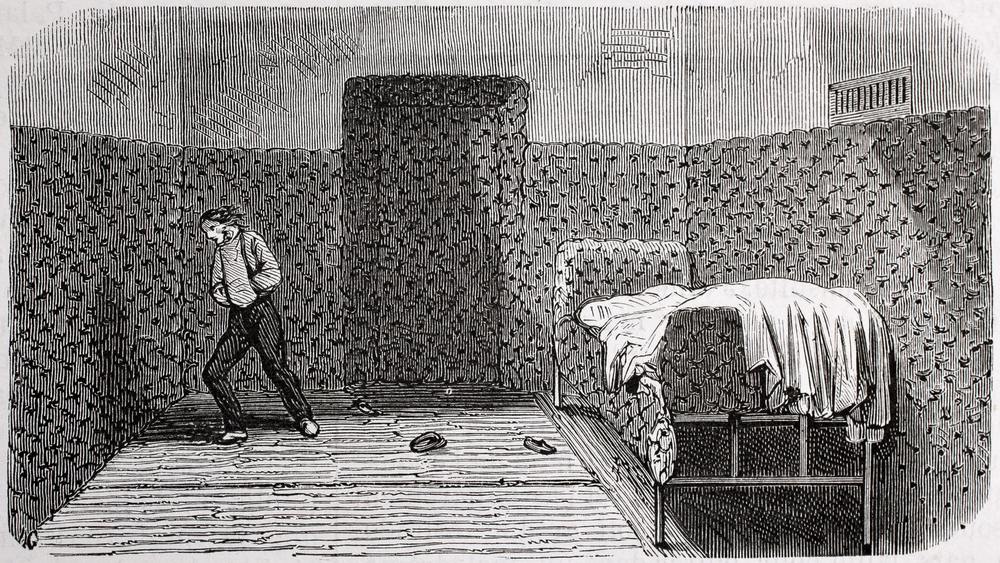

Of course, at this point in our understanding of the psyche, that “professional” will either suffer instead of you, or find the power or authority to lock that “mentally ill” person away, or worse.

But what I see happening most these days is perfectly sane people being accused of being deluded because they see something that most can’t see, or that is inconvenient for others to admit is true.

If a person knows that a relative or “friend” is committing crimes and tries to expose the criminal, it can backfire on the person if the criminal has found some “in” to the system that gives them the power or authority to get the accuser to take the fall.

In a similar way, a person who has had a paranormal experience, such as telepathy, an out-of-body experience, or an abduction can find themselves being accused of being deluded instead of being taken seriously.

So the first thing to ascertain is whether the “delusion” really is one, or is actually an unacknowledged reality. And there aren’t many of us capable of telling those two things apart.

Report comment