It has been twenty years since my last suicide attempt.

I was barely eighteen years old, and had already spent the last four years, my entire adolescence, really, in and out of the mental health system. As a girl, I had attempted suicide many times, which was the primary reason for my many forced institutionalizations. I had loads of unresolved trauma, and many very understandable reasons for how I felt. But none of these were ever constructively addressed in the various mental health settings I found myself in. On that day, twenty years ago, I left the hospital with nothing but a prescription for yet another drug in my hand, sent back to the decrepit group home where I began my adult life.

In the aftermath of those terrible days, the horror of waking up alive yet again, what I craved was a hug, a reassuring touch on the arm, a smile, or a compassionate word, but these were never forthcoming. Instead, I was treated like a criminal.

Twenty years later, I still remember the shame I felt. A burden of shame so heavy, my body and soul buckled under its weight. As I write this, my eyes fill with tears of compassion for the girl I was then. I cry for every person who has been in so much pain that they attempted to take their lives, and were met with apathy, unwanted “treatments,” a sea of diagnoses, and punitive attitudes.

After that last attempt, I was handled roughly, almost shoved from a gurney onto a hospital bed by a large, imposing man. I remember what it felt like to have the hospital worker not even look at me as he did this; as if I was a being so disgusting, so unworthy of care that I did not even deserve eye contact. The “saving” that I endured was almost more painful than the attempt itself – tubes shoved roughly into my nose while they pumped my stomach, cold hands, blinding lights. No explanation of what was happening to me.

I remember cold, detached voices, talking about my “borderline personality disorder” and my “attention seeking behavior.” Attempts were categorized as “mild” or “serious.” Professionals talked about me like I wasn’t there. Did they even know, or care, if I heard? I was a mechanical thing, a body to be saved, a liability to avoid.

Sitting on the group home couch that day, my stomach growled, but I had just a few dollars to my name, as my entire disability check went to this group home. I deliberated as to whether my remaining money should go to cigarettes or food, since the food they served at the group home was inedible slop. I couldn’t decide. I sat down on the ratty old couch in the dark, sour-smelling room, drew my knees up to my chest, and rocked, trying desperately to comfort myself.

This time, something, the dawning of a new realization, clicked inside my head. I finally understood. The people who were supposed to be helping me truly had no idea whatsoever what they were doing. They were just going to switch me around from drug to drug, hospital to hospital, placement to placement, forever. For the longest time, I had believed them — that I was too broken to be fixed. Now I was slowly beginning to understand that the system was probably more broken than I was. But I had no idea what to do about it.

In what I can only call a “moment of grace,” it occurred to me that I would have to drastically alter the way I viewed myself and the world. I would no longer define myself as a mental patient. From here on in, I would reject the diagnoses and prognoses of the mental health system and view myself as just a person again. A person with dreams and abilities– not just a cluster of symptoms or a suicidal history. I would concentrate on a new future, which would not include a revolving-door flurry of attempts and hospitalizations. Never again would I be locked up, and never again would I swallow what they dished out. I was an adult now. I would take control of my destiny.

It was not an easy road; it was filled with lingering fears that I wouldn’t be able to hack it in the real world, missteps, stumbling, and getting back up. At the time, I had no idea about the movement of my “peers,” people who had lived through similar experiences, had come out the other side, and had dedicated themselves to supporting others. But there were also many triumphs. Each time I proved the doctors wrong, and moved in the direction of my dreams, the suicidal burden, the burden of shame and brokenness, lightened a bit. And seven years later, when I discovered my tribe of other “mad visionaries,” “psychiatric survivors,” and human rights activists, I knew I had come home.

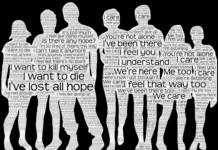

Will Hall, Laura Delano, Sean Donovan, Janice Sorensen, David Webb, and many others have talked about how we need to completely reframe the way we understand and respond to suicidal feelings. We need to see the “desire to die” as a desperate desire for life, a deeply dreamed-of life which is being torturously thwarted somehow. “Preventing” suicide is not enough; we have to give each other reasons to live and keep on living. The traditional public health approach to suicide prevention cannot do this with its spreadsheets, its pie charts, and its demographic analyses. We need a community-based approach to suicide based on compassion and true understanding. We need to stop the hysteria and misinformation circling around about suicide.

One way to do that is for people who have been suicidal to speak out. We have been among the most marginalized and silenced of all people, largely depicted only in gratuitous and sensationalist ways in the media and public discourse, or analyzed as clinical case studies by the suicide prevention field. But a new movement is coalescing, of suicide attempt survivors who are willing to tell the truth of what they have known and experienced, in their own voices, and to demand change in the way we as a society treat people who struggle with suicidal thoughts and feelings. The more of us who speak out, the better, because our stories may just give that next person the ability to put down their burden of shame for a moment and to find a safe space to talk about whatever is driving their desire to die. Silent suffering, born of shame and fear, is the true killer.

Suicide attempt survivors articulate a need to develop a whole new paradigm for crisis care. People need havens, not cold, unfeeling institutions. If people want to go somewhere if they are feeling suicidal, it should be non-coercive, non-authoritarian, and located in the setting of the person’s choice. If they wish for the comfort of the familiar and to receive support in their homes, or at a friend or family member’s house, that should be respected. If they wish to leave their current environment for a while, people could ideally spend some time getting round-the-clock support from others who have been there, in a beautiful and home-like setting, like Afiya or other peer crisis respites. There should be places of refuge and healing like these in every community in our country; yet only a handful currently exist.

In the emergency room and ever after, survivors of suicide attempts should receive the following sorts of messages: “I am so sorry you’re hurting so badly. Is there anyone you want to talk to? What do you need right now? What support do you need that you’re not getting? If you wish, when you’re ready, we can sit down together to find some ways to move through this enormous pain that you are feeling.” If people choose to or have to go to ERs, they should be met by attempt survivors who can hold their hand or offer a kind, non-judgmental presence. One should never walk out of an ER feeling like they have just been punished for being “bad.”

Ultimately, what we need most is community, a place where we can be ourselves and be accepted just as we are. In my experience, suicide is an act born out of a sense of intense disconnection and isolation. The shame following an attempt forces many of us to retreat even further into ourselves, into our stories of “what bad people we are.” True community satisfies our basic human need to belong.

I remember feeling so incredibly alienated as a young woman, misunderstood and ostracized by my family and by most of my peers. The only kids I felt comfortable with were the other freaks and outcasts at school, but we coped collectively by glorifying drugs and death. What I could have used was some truly supportive community that saw my strengths and held them up to me, that reminded me of all the gifts I had lost to a psychiatrized adolescence, such as my love of art, writing, and nature. The title of an Icarus Project publication on mutual support resonates with me so deeply: “Friends Make the Best Medicine.” The communities of which I am thankful to be a part of today remind me to call myself Beloved, to feel myself Beloved upon the earth.

I am very inspired by the Alternatives to Suicide groups happening in Western Massachusetts and elsewhere. In these groups, which are run by and for attempt survivors or people who struggle with the desire to die, folks can talk honestly about suicide, without fear of having the cops called on them, scorn, or judgment. We need spaces like this everywhere to remind us that we are not alone, and that collectively we can make meaning of life, we can collect the shards of our dreams, we can find something to live for, and something to fight for.

Today, twenty years later, I can say that I have truly gone from longing for death to revering life. Now I am a mother, having grown life within me and given birth to life, and I have sworn to myself that suicide is not an option. Sometimes I do feel that old familiar “tsunami” wash over me, that urge to die. I see the tsunami for what it is, an unmet longing within me. Today I know that all I need to do is notice the suicidal thoughts with compassion, and take some small step in the direction of what I like to call my “larger longings.” Longings to create, to love and be loved, to talk, to cry, to laugh, to be touched, to rest; or to be alone, to write, to walk in the forest, surrounded by trees, listening to the sound of my feet crunching over the leaves. When I listen to and nurture these larger longings, the tsunami retreats silently and becomes one with the ocean again.

There is a part of me that dreads the day when my son will catch a glimpse of my self-inflicted scars and ask, “what are these, Mommy?” But I will swallow hard and tell him the truth, as I have come to see it. This criss-cross of scars form the tracks where angels skated across my wrists. The cigarette burn scars on my arms are where the fairies touched me with their magic wands. They are reminders of a life I once lived. I’m glad I survived. And I will tell him that inside, too, there are some wounds that may never heal completely, but the scars do fade, with the application of love and the light of community.

Of further interest:

This is beautiful, Leah. You are an inspiration to so many and a bright light leading this revolution.

Love, Dorothy

Report comment

I guess it is good to know that some of us “make it out” and can talk about suicide attempts that are twenty years old. However, not all of up are attractive and acceptable enough in polite society to come to where Leah has in midlife. Who speaks for people like me–the fat, ugly, aging minimum wage piece of garbage who is still living in hell?

Report comment

@sharoncretsinger

You can speak for yourself. Your story is important, just as important as Leah’s. Your story is important to us. Why don’t you share it with us? If you are afraid of someone identifying you, then you can obscure any information that might be identifying.

Report comment

Sharon!

“fat, ugly, aging, minimum wage piece of garbage”?!??! WTH? To me you are beautiful and sparkling, brilliant and kind-hearted, a shining star. You may be in a yucky place right now, but something much better could be right around the corner. Stop listening to you-know-who, and get her voice out of your head! 😉 Sounds like Leah felt a lot like you do when she was stuck in that dingy, stinky group home, repugnant to everyone around her. She was a shining star then too, but that fact hadn’t been recognized yet.

Report comment

Yes, Sharon, it makes me feel bad to read such a description of yourself. I don’t know you, but I have read a number of your comments, here and on Facebook, and you are obviously a thoughtful and intelligent person.

How well I know that feeling…”I’m just a piece of shit,” and how well I remember repeating that to myself over and over, just as I was told about myself all through my childhood. I know it is easy for me to tell you that the more you repeat this to yourself, the worse it gets, but you CAN stop this vicious circle. You can. I was able to do it.

I don’t know you in person, but if I could be there for you, I would stand with you while you looked at yourself in the mirror and started to encourage yourself and tell yourself that you’re a good person.

Report comment

Leah, thanks for sharing. While I have felt suicidal on occasion, I have always kept it to myself until long after the feelings pass. It has always been the case, that finding a community that values me helped alleviate the feelings.

What I find most interesting is the following. Take the people who experience extreme fear to the point that it makes them incredibly pessimistic about their situation (some unlearned people like to pejoratively call this paranoia, and of course they also think that psychosis must also go with it). Anyway, being one of these people, I find that properly dealing with extreme fear require addressing the cause of the fear (coercion, abuse, isolation, etc). The Hearing Voices movement effectively encourages this when people start to listen to themselves. This sort of thing is best accomplished in a supportive setting similar to the one that Leah describes as being useful for people with suicidal feelings.

Could it be that the most useful thing for many of us so-called mentally ill is non-judgmental community? Perhaps a local community, or perhaps a retreat. If so, this is a good thing, because we don’t need separate retreat facilities for people with different ‘diseases’. We can also share local communities.

Report comment

Thank you for this heartfelt article.

I was in mid-life when I ended up in the hospital after being found to have almost succeeded in taking my own life. This was the result of several weeks of having been told by my former psychiatrist repeatedly that I had ‘lost my dreams.’ My mind was fragmented at the time from just having gone through med withdrawal, and I did not know the truth about myself in that moment. Had I someone who knew how to see my spirit and the bigger picture, and also to remind me that I was in a healing process–that core changes is occurring–I believe I would have listened to that, as this is the kind of information I was seeking. I would have felt calmer, assured, and supported in my healing process.

But after focusing so diligently for years on healing the effects of trauma in my early life, and also brain trauma from medication, only to be told repeatedly by my shrink that I would be limited in my life and to forget about living my dreams (‘you have to face reality,’ he said), I really couldn’t see the point of continuing to live. I was already buckling from my own nerves, and apparently, there was ‘no end in sight,’ and that was for me to accept.

After having been pumped, the ward shrink came into see me, and within 3 minutes, because I was having difficulty communicating at that moment, he was yelling at me that I was ‘all wrapped up in myself,’ and walked out exasperated. (Training??) No one–no one at all–ever asked me why I felt compelled to take my own life. I was yelled at, shamed, poorly interpreted, and accused of being manipulative. I wasn’t exactly motivated to keep living, but I didn’t want to go through all of that again, so I checked out for about a year and stopped talking about how I was feeling.

Eventually, I found my way to good spiritual teachers and healing support, finished up with the meds once and for all, and found my heart and spirit. Now I’m on track, clear, grounded, and living my dreams, and free of medication, the need for therapy, and any of the old fears. The trauma has resolved, and my brain, soul, and life have healed, so I’m extremely grateful 24/7–and I actively practice this gratitude after all these years.

But for sure, I am alive and happy no thanks to mental health care, whatsoever. In fact, quite the opposite. The mental health care that I received led me to not wanting to live any longer. They gave me NO HOPE of ever living a healthy and productive life as I had envisioned, and of course, I proved them wrong, thank God.

Great luck with this work! More than saving lives, I see it as vital soul-nourishment.

Report comment

Correction: core changes *are* occurring. (Thanks for bringing back the edit button. I will remember to use it next time!)

Report comment

Hi Leah. Hugh Massengill from Oregon here. We met at an Alternatives a couple of years ago.

I really agree with Dorothy Dundas’s comment that you are an inspiration. I can only wish your words and life are held as an inspiration to the mental health system itself, that those still drugging and with great determination not listening to suffering people will wake up and start asking “who are you, what happened to you, how can I help you?”

I found with my own suicidality that it was massively logical, and the way out was for me to understand my own suffering, to champion that utterly destroyed 16 year old inside. If I had had a support group in high school, people I could talk to about the insanity in my family and community, that horrible pain would never have taken root inside me.

Imagine a Psychiatric Survivor “Bible” that included words and video of the real experts, people who have listened to psychiatry and found it wanting, who have found a way to real peace by remembering love and friendship.

Hugh Massengill, Eugene

Report comment

“Hope deferred makes the heart sick, but a longing fulfilled is a tree of life.” (Prov. 13:12) I just posted that scripture on another piece, but it fits even better here. Leah, I loved your description of the medicinal qualities of “a longing fulfilled” – even a longing as simple as a walk in a beautiful place.

Report comment

*big hug*

Report comment

Thank you for this, Leah.

It is giving me hope to hear (okay, mostly read) more and more stories like this. Right now, MIA is my only “community” for this type of support. I am attempting to create it where I am, but it is difficult walking this tightrope between being a “professional” and a “peer” – that is, between working as a “therapist” in mental health settings, and between continued experience of debilitating emotional/mental distress – including ongoing thoughts of suicide. Thanks to what I have found through Robert Whitaker, I will never call myself mentally ill again. I hope to never be hospitalized again. I hope to gather enough strength to add to the love and support beginning to grow in my community (barely), instead of falling into weakness. I suppose the balance of that is finding a collaborative and connective way to share my weakness with others. I love the way you express your thoughts and feelings. Every paragraph holds personal meaning for me, and I plan to share your post. Thank you.

Report comment

Wonderful, beautiful. Thank you, Leah.

Report comment

Hi Leah:

I’ve been searching for resources to address suicidality “upstream” – before it occurs. Your post is enlightening.

I used to blog about my search for care, support and resources, and although the blog is dormant from lack of interest, the reading list page might be of use as it is a compilation of resources which may address some people’s needs.

If you are interested in expanding eastward toward the metro Boston area, please get in touch.

And thank you, too, as always to Robert for hosting this website, as well as to the commenters who bravely share their experiences of distress and their journeys to alleviate it.

Report comment

Shoot – the link didn’t stick. The blog is called Incompatible With Life on WordPress. http://incompatiblewithlife.wordpress.com/reading-list

Report comment

Thank you so much for this. I cried while reading this. It’s been 23 years since my last attempt, and one year since I last self-injured. Seeing myself as human and not “bad” has been a real challenge, and you said everything I want to say, and more.

Report comment