This week we launch Mad In America Continuing Education. It is an enormous privilege to be a part of this project and to proudly announce that the first course offering is a series of lectures by me on neuroleptic drugs. I review the history of the development of these drugs as well as their short and long term effects. I discuss what conclusions I have drawn from the data; I recommend that we need to work harder to keep people off these drugs or – if we use them – to minimize the dose and stop them as soon as possible.

But there remain other pressing concerns for those individuals who are currently taking these drugs. There is almost no guidance on how to implement what should not be a controversial statement – it is better to be on as small a dose as possible. We are caught between competing models of practice and vast territories of the unknown. If someone is started on a dose of medication in a hospital over the course of a short stay, we do not know if that dose is the minimally effective dose.

There seems to be no escaping the conclusion that – at least over the first two years – the relapse rate will be higher when the drugs are stopped. Our current system of care prioritizes preventing relapse over other concerns – metabolic syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, brain atrophy, impaired functional outcomes. Since these drugs have been with us for 60 years and for at least 30 years it has been axiomatic that everyone should be advised to remain on the drugs indefinitely, there are many people who have been taking them for many years. If one begins to question current treatment guidelines, it is unclear how one can safely reverse course or even if it makes sense do this.

I came to the conclusion that the principle of informed consent obligated me to share these questions – proactively, not just when individuals were complaining – with the people I see. As I have done this, I invited people to try – slowly – to reduce their doses and I have been tracking my experience as some people choose to taper their dose and others choose to leave things alone.

The group I will describe in this post are those with whom I had this conversation over a year – May 2011 through May 2012. I have been tracking them since and in this blog I will report on their status as of May 2014. When people wanted to reduce, I suggested that we reduce by ~20% of the initial dose not more frequently than every 3- 6 months. Since this was not a study, just a recommendation, what people chose to do varied. Some who initially wanted to reduce, changed their minds. Some who initially did not want to change, eventually decided to try it. This makes it harder to summarize but it is the way things work in clinical practice. The decisions were very much driven by the person taking the drug and first and foremost I respected those decisions. At the same time, I had some people who chose – against my advice – to abruptly stop taking the drugs. Almost all of these individuals had done this before. Their outcomes were so different that I decided to track those as well and compare them to the other groups.

If you look at the past posts on this project (here and here), you will notice that the numbers have changed. That is because in the second year, I combined my data with that of a colleague who was doing something similar in her clinic. However, she was not able to continue this tracking so for year three, I am just reporting on my own experience following 80 individuals.

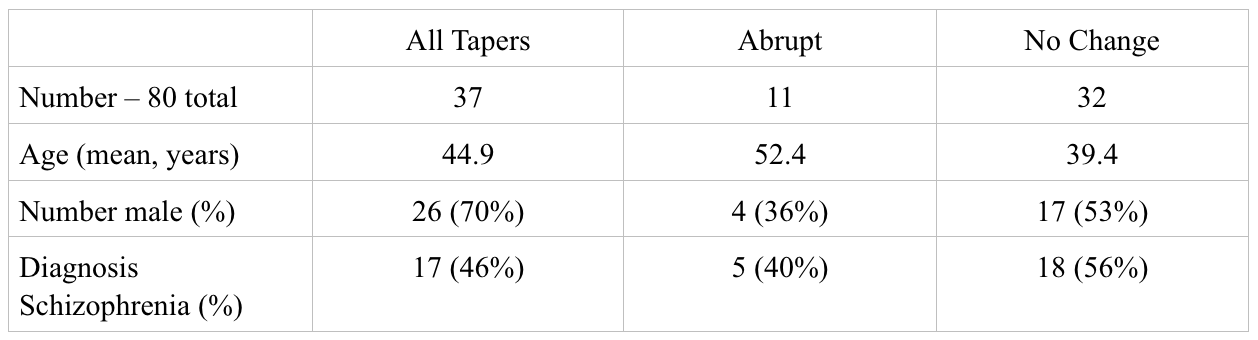

The following chart includes demographic information. “All Tapers” refers to all of the individuals who at the initial point indicated an interest in tapering. Similarly “No Change” refers to those who at the outset, did not want to reduce the dose, and “Abrupt” refers to those who abruptly stopped taking the drug. People changed from one group to another over time and I will discuss this below.

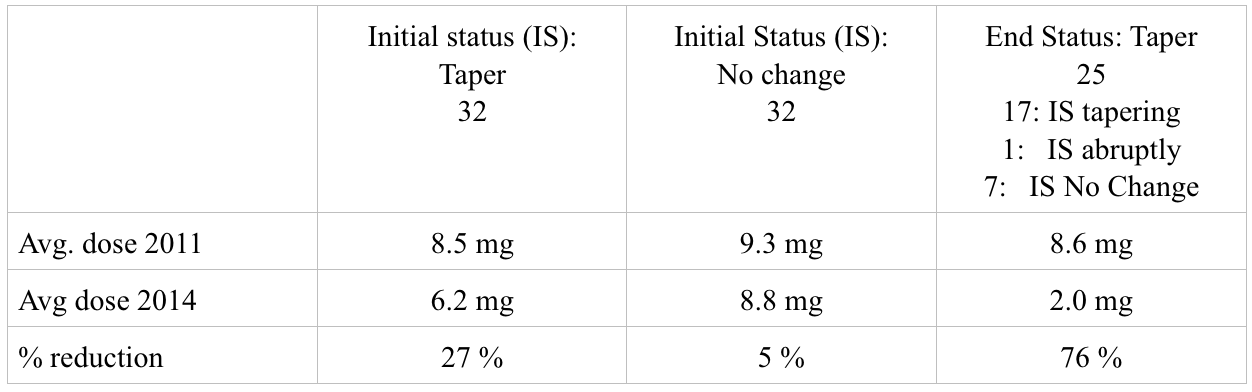

The next table includes the average dose of drug for each group. Since people were treated with many different types of drugs, I converted them into risperidone equivalents using the table found here. While I am not sure this conversion is valid in the sense that we are not sure that these drugs at these doses work in equivalent ways, this conversion helps to measure the percent reduction. Therefore, I use this more as a guide to measure the changes in dose rather than as way to evaluate the absolute dose.

The first two columns provide information on those who, at the outset chose to taper or not, respectively. Since people changed status over the course of the three years, I also calculated the total dose reduction for those individuals who were tapering their dose at the end of the third year. This includes the 17 individuals who from the outset indicated a desire to taper and stuck with this over three years, 1 individual who abruptly stopped and did not do well eventually stabilized and then began to slowly reduce the dose, and 7 who initially did not want to taper but then changed their minds and began to do reduce the dose of the drug. While the reductions in the initial taper group are modest – 27%, they are substantial among those 25 individuals who continued to taper over three years – 76%.

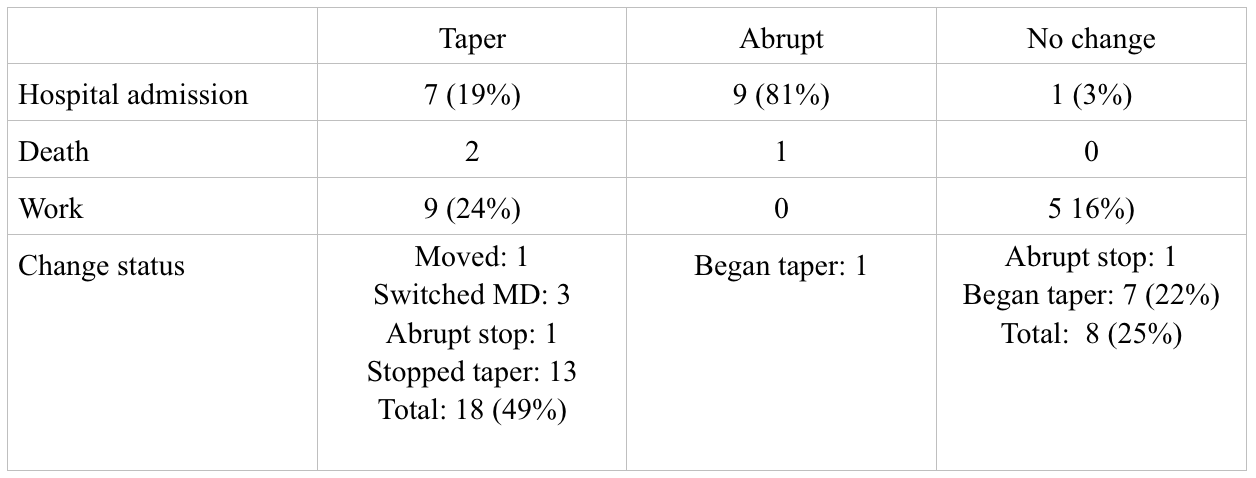

The most pressing question concerns what happened to these individuals. Since the biggest worry for some is that people will become psychotic and require hospitalization and since admission to hospital is easy to track, I include that information in the following chart. There were three individuals who died during this three year span and although in my opinion and that of others it was unrelated to the taper, I report on that here. I was also able to track who was working at the end of the third year. And finally, to give some sense of peoples’ attitude about this process, I include information regarding who changed their status over the three years. The categories- Taper, Abrupt, No change – in this chart refer to the person’s initial status.

I also looked more carefully at the work status. Of those who remained with the taper over the full three years – the group who was able to reduce dose by 76% – 8 of the 25 (32%) are working. Among those who never tapered or started and stopped the taper – this includes 43 individuals in total, only 6 (14%) are working at year three. This also compares to an employment rate of ~ 17% in the program in which all of these individuals are enrolled.

I am hesitant to make too much of this. This is, after all, a chart review and the numbers are small. Also, even if this trend were to hold up with larger numbers and in a more rigorous trial, correlation is not the same as causation; I can not say that the dose reduction was the reason why people returned to work. However, it is interesting since one of the main reasons to try this – to accept the risk of a recurrence or worsening of psychosis – is the data suggesting that the drugs negatively impact functional recovery. These results go in that direction.

I would add that knowing these individuals, I can think of other reasons why work may have increased. It may not be a direct drug effect – although at the very least, less sedation would certainly help a person feel more like getting a job. But the conversation itself is a recovery-oriented conversation. When we talk about reducing dose, we are talking about ways of thinking about the problem that counter the notion that there is a fixed problem with a fixed treatment – drugs for life.

The conversation includes the uncertainties involved in the decisions but in doing so, it empowers the person to be active in the decision making about his treatment and his life. I say to a person, I am not sure what is the best option for you, it is your life and I need you to make this decision with me. It embodies the notion that what happened to a person at one point in his life, may not dictate how he lives his life indefinitely. It is certainly possible that those conversations contributed to the increased interest in getting a job, the increased confidence in being able to work, the notion a person may have about himself, that he can be a person who has a job.

I started this tracking because I thought this information would help me and those who consult with me. They know I am doing this and I share – anonymously – my experiences with them. However, I knew I would remember and be influenced by the worst outcomes. This is true. These days, my memory sometimes fails me but I can tell you about every person who was in the hospital. And while almost all of these individuals are doing OK now, it has been wrenching in some instances.

I have been surprised; I am humbled once again by what I do not know and can not predict. With some, the alliance I thought I had and hoped to keep through the process was lost. This has been integrated into the narrative I tell people as we make these decisions together. I think this has been and will remain a challenge for psychiatric practice. The gains are important – in my opinion vital – but one experiences them in a more subtle and less dramatic way. If I had not kept track of this, I think I would have a good estimate of how many people were hospitalized. I would not have a clue that 32% of those who tapered were now working as compared to 14% in the other group.

Sandra: At one time or another I have been on lithium, Thorazine, Prolixin, Haldol, Mellarill, Depakoate and, Abilify,. I am currently tapering from 1mg of Zypreza and I continue to take .5mg of Klonopin and a dose of hydroxene. I also take synthroid to counteract the damage caused by lithium which all the doctors say caused the drop in my kidney function. I am taking the tapering slowly and don’t have any outwardly negative health effects after this all started with an involutary commitment in March 1989. At times this causes me bouts of anger since it appears that the very basis of psychiatry is on highly shaky grounds, and that the my sins leading up to the commitment were basically trivial. Thanks for trying to save others from this fate.

Report comment

Thanks, Chrisreed. Would you be willing to share more details about your taper? I think this is valuable information. I have been told that it can get tricky at the very end.

Report comment

Sandra: I believe that Zypreza titration is extremely difficult. I have noticed in the past that irritability tends to creep in. Thankfully, my family and work situation are a little less stressful and chaotic this go around. If I notice I have slept less soundly the night before, I will take a little extra Zyprexa the following night. I have been at or around 1 mg for the past 4-5 months and I have not gotten up to take an extra dose because of sleeplessness during this period. I have a two week vacation coming up, so this will allow me the opportunity to lower the dosage a little more. I remain fairly active walk 3-4 miles per day in the hills. I am 20 lbs overweight as opposed to the fifty that I experienced under the slew of medications that I was on. Still pretty angry about the damage caused to my kidneys by the Lithium.

Report comment

I think that maybe when going down or up with low doses of Zyprexa, you largely change its effects on receptors such as histamine H1 and serotonin 5-HT2A, based on affinity data I just looked on. That is, maybe the effects of Zyprexa on these receptors reach a maximal potency, or “saturate”, on a relatively low dose. That is, when you increase the dose further, this effect won’t increase much anymore. For instance, you could get a similar sedating antihistamine effect from some older OTC (in USA) antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, then again they would perhaps have similar adverse effects!

In any case, maybe part of the reason for drugs such as Zyprexa and Seroquel is that they sedate people, through their strong action in histamine and other receptors already in low doses. ?

Report comment

To elaborate further, if there’s an issue in stopping drugs such as Zyprexa or Seroquel, maybe it’s because they’re very sedating already in low doses? This sedation also gives good sleep and so on, which tends to improve well being in longer term if that has been an issue. On lower doses, these drugs are not operating so much on “neuroleptic” dopamine receptors, and should perhaps be compared to other drugs, based on receptors they affect on those low doses.

Report comment

Hermes: I doing I decent job of managing my weight and life issues. I think lower dose of Zypreza is an improvement. Would like to be off it all together. We’ll see.

Report comment

chrisreed,

How are you getting to such low doses? do you use a compoinding pharamcy? I know that is very expensive. When I had my article published in the Washington Post, one commenter said he used a nail file to shave the drug. He would reduce by 4 shavings at a time. I am suggested this to some people but I have no data or experience. I am just sharing because if you are not dealing with a capsule, it seemed like a clever approach.

I think the sedating drugs may be harder because of the rebound insomnia but I have had people have trouble as well with the less sedating drugs.

Thank you both for sharing what you have learned. Outside of user forums, I have not seen this kind of careful discussion if taper. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry just published a report on tapering olanzapine and risperidone.They reduced by 50% and then followed people for 6 months. Their group did pretty well. they looked at receptor occupancy.Their goal was not to stop the drug but to establish the minimally effective dose. I would not do it this way since I am not going to pet scan people but this kind of discussion in a mainstream publication signals that people are thinking about this. If I have time I will blog about this but here is a link.

http://www.psychiatrist.com/jcp/article/Pages/2014/v75n11/v75n1102.aspx

Report comment

Sandra: I have been breaking the pill into smaller parts and gradually taking smaller doses.

Report comment

Sandra: “I think the sedating drugs may be harder because of the rebound insomnia but I have had people have trouble as well with the less sedating drugs.”

Yes, in one discussion board I read about many people having issues with sleep when trying to quit a low dose of quetiapine, such as 25 mg – 100 mg. It’s already very sedating at 25 mg because of at least its actions on histamine H1 receptors, and their body was used to the sedating effect. I personally found that when tapering, 12.5 mg was enough to give me sleep when needed. After some time on 12.5 mg, I switched to melatonin. But yeah, different neuroleptics may have different issues when tapering because they affect different receptors or work in a bit different way. Abilify at full dose actually caused me to wake up several times at night and a low dose of quetiapine perhaps helped me sleep a bit better. I personally actually didn’t have much issues in stopping Abilify, though I don’t think I should have been eating it to begin with.

Report comment

LOW DOSE SEROQUEL/QUIETIAPINE

Hermes

I’ve had the same experience on low dose SEROQUEL 12.5mg is enough to send me fast asleep, and half this again works. There’s also a rebound insomnia attached to withdrawal at very low doses – but an improvement in overall balance (I think this is because Seroquel has a very short half life and mild daily withdrawal symptoms). But the rebound insomnia can effect performance.

What you’ve said about seroquel not being ‘antipsychotic’ at low doses (I think under 160mg/day) is very useful to someone withdrawing from other ‘antipsychotics’. With me, 25mg/per day of Seroquel replaced 25mg/day of Mellaril. I found the drug Mellaril to have a type of dopamine withdrawal syndrome (movements, anxiety etc). Also Seroquel has anti Parkinson compounds added? It is also a very toxic and dangerous drug?

COST: NHS funded Seroquel was about 100 times more expensive than the drug it replaced (Mellaril).

Report comment

Fianchra, yes, I experienced that even very low doses of Seroquel are very sedating and even tiny doses such as 12.5 mg or even less can enable sleep. I also noticed a distinct difference in the sedation effect between 12.5 mg and 25 mg, 12.5 mg didn’t cause so much sedation but was enough to cause sleep.

Both older and newer neuroleptics work in a similar manner on the same receptors in body. Each drug is made of molecules, and in body these molecules may affect different types of receptors. For instance, all neuroleptic drugs block dopamine D2 receptors in large doses where they are used for controlling psychosis. At doses of Seroquel 25 mg, the Seroquel molecules don’t go so much in dopamine receptors, but they go have a large effect in histamine H1 receptors, which causes much of the sedation in that dose. The Seroquel molecules also tick other receptors besides histamine H1 and dopamine, also based on dosage, which contribute to its effects.

That drug Mellaril you mentioned affects on a similar set of receptors as Seroquel and other neuroleptics, but these drugs have differences in how much they act on different receptors and thus what effects they have. For instance, Seroquel is very strong in blocking histamine H1 receptors, so it’s very sedating in low doses. Other neuroleptics that are not so sedating usually have molecules that don’t go so likely to histamine receptors.

Report comment

Hermes

Thanks for the feedback.

Report comment

Fianchra, I don’t know so much about how these drugs affect different receptors in body, but I’ve noticed that in practice, neither do the psychiatrists or other doctors who practice these drugs. You generally don’t get much interesting information about pharmacology, etc, of these drugs from psychiatrists, though it’s supposed to be their speciality.

Report comment

Yes Hermes

And decent doctors like Peter Breggin acknowledge this.

Report comment

I see a bit of a good beginning but that’s it. The biggest problem that jumps out at me is that 70% of the participants in this are male. If that matches with at least the approximate gender percentage of people who are on it then that may give this problem a proper perspective but historically from what I’ve read so far most if not all of the initial research data was also based upon solely or mostly the interaction with the systems of male’s. Without proper documentation of comparable samples we don’t know how or if gender matters in the process of withdrawal.

Report comment

I agree that this is just a beginning. But with regard to the 70% males- that was in the group who decided to taper. the abrupt group was 36% male and the non change group was 53% male. I am not sure what to make of this beyond pointing out the women in Vermont tend to be very independent minded!

Report comment

An important study. Can you share if the deaths were natural, as opposed to due to suicide or accident for example? Two other questions I thought of: Did you track how long or how many years people had been taking neuroleptics before the study? What diagnoses were included besides schizophrenia? Thanks for reporting on your work.

Report comment

They were natural causes. I have not collected information on how many years people were on medications prior to beginning this study. It variable but I did not include those who were fairly new to the drugs since during this same time period, I was working very hard to minimize dose in all of those people I saw. The diagnoses other than schizophrenia were primarily Bipolar disorder.

Report comment

Re: “… 32% of those who tapered were now working as compared to 14% in the other group.”

The unemployment rate for people with ‘chronic mental illness’ is reported to be around 80%. Much of this due to “medical treatment.”

There ought to be a campaign:

“Lose the treatment. Gain back your life.”

Duane

Report comment

You would think that a country with a $18,000,000,000,000 debt might like to see some people go to work, and get off federal assistance.

This could be done by encouraging them in their effort to break free from psychiatry; providing resources and supports to assist them as they slowly taper OFF these drugs.

The status quo makes no sense.

Do the math:

http://www.usdebtclock.org/

Duane

Report comment

The country doesn’t want these people in particular working, not in real jobs anyway. Its millionaire politicians are owned by multi-nationals, multi-nationals that thrive on poverty and a high unemployment rate. Major corporations love the competition for jobs, jobs that people in the mental health system have no chance of qualifying for, let alone, holding down.

Other questions would involve the kind of employment. Are they selling old clothes, or pushing mops? Are they riding mowers? Do they sit in an office cubicle? Are they working in the mental health system? Shit jobs are just that, shit jobs.

Another thing, if you’ve got people with labels working in the service industry now, and in the mental health service industry especially, this involves the developed world utilizing products made in the developing world, a trade off that is anything but fair.

There are all these homeless people camping out in the woods. Tell me, if employers weren’t more interested in hiring a certain amount of people to make for the moderately wealthy to well to do that this wouldn’t be the case. As far as I’m concerned, the human condition is a fabrication created by certain people in order to feel better about themselves at other people’s expense.

Report comment

Discover and Recover

I can prove (in my own case) that the prescribed medication caused my disability. When I took control, I didn’t stop medication; I cut it to a small percentage – less than 5℅ of a maintenance dose (and this worked).

The disability costs the country a fortune, but the profit concentrates itself among a small group of people, that can use the funding to bribe doctors, experts, the media, researchers, politicians etc. ; and this keeps the show on the road (worldwide).

Report comment

Sandra,

This is great info. about working with individuals in a more transparent way, using shared decision making with meds…I really appreciate your results and your ongoing attempt to explore how to reduce/discontinue neuroleptics in the best way possible.

Your suggestion that we also need to continue to explore how to keep people off these drugs in the first place is so important. My son has continued to do well 4 1/2 months after a two week extreme experience (which could also be called ‘psychosis’ ) last summer and he only used benzos very briefly to get back on his sleep/wake cycle. I believe that dialogue and individual and family support can really work…avoiding the hospital and heavy meds may be both possible and the best of all alternatives. I can’t imagine that he would be doing as well as he is right now…getting all A’s in his second year in college…if he had been hospitalized and put on neuroleptics last summer. I look forward to your courses!

With much gratitude,

Cindy

Report comment

Thanks again for sharing this important story. At the MIA Film Festival, I met two other parents who had similar stories. They were both professionals in the field who happened to have children who experienced extreme states. Because of their knowledge of traditional treatment, they did what you did and had similar positive outcomes.

It is good to hear from you and I am so happy to know that your son continues to thrive.

Report comment

Truth: I believe that was all that I needed when I was roped into the psychiatric system.

Report comment

Just saw your comment…so sorry to hear all that you have been through…best wishes to you…

Report comment

Hi Sandra

a great piece of work, that is helpful to those of us who are involved with helping people reduce medication. When I am working with people to come off meds there are 3 things I look for , that people are willing to do the work on what has happened in their past, that they are willing to do the work on their emotions which come through very strongly as they reduce medication and that they have a plan of who they want to be and what they want to do with their lives med free.

We have found a 3 month intensive piece of recovery work means that people can withdraw more quickly because they are working on all these things in a safe environment and for 8 hours a day, which is probably the equivalent of 5 years working with someone an hour a week. This environment is enhanced when it is in a beautiful place and peoples spiritual needs are also met. I think we need to turn services on their heads . If we id intensive work with the person , we find narrative approaches particularly helpful many people would not be stuck in a maintainance system that can go on for years, the savings both financially and socially would be huge

cheers

Karen

Report comment

Thanks,Karen. BTW- we started a Hearing Voices group. I do not want to say too much out of respect for the group but one thing that I can say is that there has been intense interest and very active participation. Thanks so much for your help and inspiration.

Report comment

It’d be great if all clinicians kept track of their patients in this way. If we are for “evidence based medicine” then doctors have a responsibility to know how what they’re doing works in practice.

Report comment

Thanks,B. There is so much focus on randomized controlled trials that clinicians tend to discount other types of knowledge. Many years ago, when olanzapine(Zyprexa) came onto the market, I did a similar thing. At that time, I was enthusiastic about this drug and wanted to track who did well on it. One thing I did not track initially was weight since not much was said about this when the drug was released. However, after a year, it was obvious that people were gaining weight. So I bought a scale and started weighing everyone. Just relying on simple observation, I learned that this drug was associated with profound weight gain. I then watched as leaders of my profession quibbled for about five years over this because of the conflicting results of the “experimercials” that were lauded as the gold standard for evidence. This had a major effect on my development as a critical psychiatrist.

Report comment

Yeah, one should never trust a trial where any of the authors declare conflict of interest with a pharmaceutical company or have received any funding from them.

Report comment

Hi Sandy-what about supplementing with dietary anti-inflammatories, N-acetylcysteine, and perhaps something to target NMDA receptors (e.g., sarcosine)? For publishing, numbers are important, but I’ve read “letters to the editor” on case-studies.

Report comment

Hi Jill,

These are interesting ideas. Cost is always an issue and I have been confused about which supplement(s) to offer. It is a daunting field with many variables and multiple opinions. I have had extensive contact with Bonnie Kaplan, another MIA blogger and I have read many of her papers on micronutrients. I have offered these to the folks who would take them but many decline. It is hard to know if something is “effective” because we are looking for the absence of problems. I realize that one could say I am too worried about exposing people to things that they might not need than I should be but I work pretty exclusively with people who have limited financial resources and I want to be sensitive to that.

Report comment

Wonderful work Sandra…and work that I wish was replicated by many psychiatrists. and I love the idea of fully monitoring weight, and also adding other concerns such as blood pressure, blood glucose levels, metabolic panels, etc. This should be standard practice for any doctor putting a patient on an antipsychotic. The tapering process is often complex, with lots of stops and starts, reinstatement, cold turkey experiments, complexities of poly pharmacy tapering, med changes, etc…very hard to track exactly, and I really applaud your efforts.

Report comment

Thanks, Jonathan. I think that these days it is far more common- and part of recommended practice – to follow weight, blood pressure, and metabolic panels. I was talking above about what happened in the mid-90’s. I also agree that tapering is – and should be – complex and highly individualized. It is hard to know how to present this data. Some people were on other drugs and sometimes those drugs were tapered based on the person’s individual situation and preference. In this report, I focused on the taper of neuroleptic drugs only.

Report comment

“I think that these days it is far more common- and part of recommended practice – to follow weight, blood pressure, and metabolic panels.”

Yeah, and when the patient gains weight and has abnormal blood panel get him on more drugs to treat the side effects and side effects of drugs that treat side effects… – repeat until the patient dies – and/or tell him to change his/her “unhealthy lifestyle”.

Sorry for sounding cynical but that’s just reality.

Report comment

First of all, I’m sorry that I haven’t read all the comments. But I do want to respond to your article, and on the basis of personal experience.

I’m tapering off medication. I’ve been doing it in small steps. After trying to stop all in one shot, and suffering from bad results, I was finally told by my prescriber that the neurons in the brain adjust after 6 weeks to a new dose of this stuff. I stepped down what I was doing at a quarter dose at a time — based on what I was taking, of course — and it’s gone very well. I’ve had changes in mood and thinking, but after a short time I’ve gotten back to “normal”.

When I went on “medication” I needed something to slow down what was happening in my head. The voices, the delusions: the intensity was too much to survive. But after a few months, when I’d slowed down, the drugs no longer helped me. What they did was kill my ability to think, to feel, to interact with other people. They slowed down my psychosis, yes, but at the same time they took away everything else: my ability to be human. I don’t believe these drugs are entirely wrong, but I believe that they should only be used for the shortest time possible. As a brake, to halt the psychosis — not as a long term solution. In the end, they were killing me. I gained 100 pounds, developed diabetes, and finally spent my hours staring into space. I’m a writer. I write books, and do very well at it. Yet these drugs, while I was on them, were destroying my ability to write, to dream, to imagine, and to be one of the human race.

Please keep doing your research. Get people to look at all this stuff, and to do the research that shows what they really do.

My thanks.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your story.

Report comment

As a nurse who began helping young adults in the throws of withdrawing from neuroleptics 3 years ago, I have little else, save the time frame, in common with the work you are doing, Sandra. The mere concept of a practicing psychiatrist embarking on a study of such paramount importance, was confined to the musings of this overly idealistic critical psychiatry convert. I am but one of many who shares grave concerns about venturing into yet another vastly uncharted terrain that maps the bio medical paradigm of psychiatry — and one of the very few who will go there, despite the risks.

I was called in to witness case after case of an 18-28 year old who adamantly refused to continue taking neuroleptics — usually fairly high doses. The situations were linked to recent inpatient admission, first episode and post sudden cessation of psych drugs, or *relapse*– extreme mental states being the reason for locked ward *treatment*. My role was to intervene in the crisis that the young person’s decision to refuse to continue taking the drugs caused– . Between a rock and a hard place was my position at the point of encounter. Back against the wall, I faced the frightened parents and significant others of these young rebels, asking me point blank: “What is the alternative to these miracle drugs?”, or pleading , “Can’t you just convince him/her that this is the only help there is?” As liaison to their support systems, I did not have much breathing room. Tapering was a means of forestalling the consequences of this stand off, or rather, another inpatient admission. But it was everything else I added to my tool kit that made all the difference.

I developed a holistic approach that encompassed the symptoms of precipitants to locked ward admission and the traumatic experience of the admission. Start to finish,trauma reactive behavior – informed the care plan.

First steps were focused on eliminating stress/anxiety and teaching the basics of sleep, diet, exercise hygiene. All individualized by necessity, but with emphasis on creating rituals, routines and time for documenting and reviewing them. Aromatherapy was/is the most popular for sleep/rest/relaxation. Low glycemic and gluten free diets are the easiest to implement. Exercise programs were formulated during foot soak/massage intervention- unless refused, which rarely happens. The more grounding techniques introduced, the better– is my motto. The main focus of each encounter is learning all about the person who is agreeing to listen to any advice I might offer.

The one area I find to be of most concern to young adults who have been exposed to neuroleptics, is cognitive function– decreased attention, poor short term memory, slowed collaborative brain, or higher executive functioning. I have had the best results employing two approaches to *cognitive remediation*; brain *games* ( I have a hand book from Kate Tchanturia and Janet Treasure, psychologists at Kings College London), and a balance board I bought on-line from *Balametrics”- http://www.balametrics.com/ Dr.Frank Belgau’s innovations.

The information I have received that resulted from building trust over time, is that the tapering protocol was rarely followed. My group of neuroleptic withdrawing candidates were all pretty much die hards in their original stance against the drugs. All of them fall into the category of victims of a flawed paradigm that dictated neuroleptics as first line treatment, and all were motivated to defy their diagnosis and remain out of the hospital/ER. The ways in which their goals were accomplished could never be set down in protocols — but the holistic approach to establishing health and balance in their lives did serve as an excellent foundation for their success. And, like any clinician who dares set down in writing a successful *treatment* plan, I also have encountered the *one* person who defied everything, but her own intuition. She is the hero of her own story.

I look forward to more mainstream acceptance of the need for guidance and expertise to meet the needs of the incoming wounded– all casualties of poisoning by psychiatrists. WE need to be able to talk and collaborate openly– take the *taboo* out of saving lives– resolve the paradox of the health care industry, so to speak.

It was a pleasure to meet you at the MIA gala dinner, following your courageous performance on the psychiatrists panel. The power of your self disclosed transformation was literally contagious.

Thank you,

Katie

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your experience with young people. It was also nice to meet you after our spirited beginning here at MIA!

Report comment

I the case of my son, tapering is not the problem. Getting off the neuroleptics completely is. I believe that most people will do well on doses that are well below the lowest recommended dose.But, what caused them to become psychotic in the first place, and revert to psychosis when off the drugs entirely? I place my trust in time, therapy and maturity. If someone has been “misdiagnosed,” then IMO there s a good chance that the drugs really are the problem, but then there are people like my son, who are intelligent, sensitive, and on a journey that defies the idea that there are biochemical answers to spiritual questions.

Report comment

Rossa,

In my lecture series, the conclusions I draw are this:

1. Dose matters – there is less harm in being on a lower dose and the way the system is structured people often get started on higher doses than are necessary. It is worthwhile to have this discussion and try to determine the minimally needed dose.

2. Whatever the “minimum ” is may change over time so this can be revisited again and again of a person chooses. We make recommendations based on studies done over two years but people are on the drugs for decades. Over decades, these drugs appear to interfere with recovery and this also appears to be a dose related effect. So for some people, getting off the drugs may not be the goal but if you can help someone reduce the dose by 80%, you are probably doing a good thing for that person.

Report comment

The lower dose probably also makes the development of secondary illnesses (diabetes, obesity, dyskinesia…) less likely.

Report comment

B-There is very good evidence that dose impacts most effects of the drugs- tardive dyskinesia, muscle stiffness, sedation. I think it is less clear of dose impacts propensity to gain weight. There is also already good evidence that for those experiences first episode of psychosis that the dose required is lower than what is typically used. However, there is also evidence that doctors do not follow those established – mainstream – guidelines. The NIMH RAISE study of FEP is beginning to publish results. They found that when people were referred to this study, many were already on doses that exceeded the evidence based recommendations.

I know that there are people on this site who want to completely eliminate the use of there drugs and the role of psychiatry. However, there is much harm reduction that can be achieved if the idea is pushed that if one uses these drugs they are prescribed at the lowest dose possible and that dose minimization remain an active goal. This is actually a non-controversial idea – or at least it should be – since there has been evidence to support it for decades.

Report comment

“I think it is less clear of dose impacts propensity to gain weight.”

Sandra, are you referring to some specific studies which suggests dose reduction didn’t help with weight gain, or that there haven’t been studies of it?

It probably depends on dosages, drug in question and other factors as well. For instance, I think some neuroleptic drugs that often cause weight gain affect strongly in histamine H1 receptors, and it has been suggested this is one factor why they cause weight gain. (They may cause weight gain in other ways too, this is just an example.) The effects a drug has on different kinds of receptors doesn’t grow linearly with dosage, so that even a relatively low dose of Seroquel or Zyprexa may “saturate” those histamine receptors, or other receptors, so that going from a massive dose to a big dose doesn’t necessarily have much effect on weight issues. As an example, 25 mg of Seroquel already caused me huge “munchies”, maybe because of the strong activity on histamine receptors at that dose. I don’t think the “muchies” effect would have grown linearly up to 600 mg or have had much change from 400 mg to 600 mg.

Report comment

Our official (Finnish) guidelines also currently state things such as neuroleptic medication should be kept to a minimum dose in order to prevent unwanted effects, tapering down can be attempted after the patient has been symptom free for a year or two, etc. Not all of that actually sounds so bad for a disease so grave as psychosis, as it is described in those guidelines. It’s that what I saw and experienced there was something entirely different.

Report comment

Yes, Hermes. In this respect, practice does not follow guidelines. But with regard to weight gain, I am just speaking from personal experience. From this experience, I would say that reducing the dose does seem to make it any easier for people to loose weight. Some are able to loose weight after some years but for others they only loose weight when the drug is stopped. I have other patients who still have trouble loosing weight even once the drug is stopped. Since many of us have trouble with being overweight, it is hard to to know if the prior exposure to drugs is what is contributing to the difficulty in loosing weight.

Report comment

Sandra: I believe that obesity rates vary greatly from one region of the US to another. Also varies by social class. My sense is that where obesity is highest, sedentary life styles are mostly to blame.

Report comment

It is just pretty striking when someone starts a drug, gains 30 lbs fairly quickly, stops the drug, and loose the weight quickly. I have seen this happen when the person is not so aware of trying to loose the weight. By all means, though, the causes obesity are multi-factorial.

Report comment

Yes, I have nothing against the idea that you can actually lose weight by quitting neuroleptics – I did so and lost those 25 kg I gained in the “process”. I lost that weight, and actually got interested in nutrition, in severely restricting my sugar intake. After all of that crap I experienced, I think that at least for me, it’s best to restrict my carb/sugar intake. I also think that the basic reason drugs such as Zyprexa and Seroquel cause weight gain is somehow related to sugar/carb metabolism. and stuff. Maybe.

Report comment

And I’ll add to it: what worked for me personally, was to restrict carbs quite severely, and to teach my body to use fat as fuel. The results were great.

Report comment

I actually think doctors who talk to overweight people who take these weight-creating and diabetes-creating drugs such as Zyprexa, would do great if they told their patients to eat a diet which restricts carbs and sugars severely, promotes fat, etc. It may sound crazy, but yes, what worked for me was to eat lots of fat and to avoid all sugar.

Report comment

Doctors are supposed to know about metabolism that happens in body, how their drugs affect their patients, and other issues.

Peter Attia’s “low carb” blog may not be directly related to the side effects of “atypical neuroleptics” .. He knows a lot more about biology than I do.

http://eatingacademy.com

Now I may be personally biased, but I gained 25 kg in a short time after taking the drugs .. and lost that 25 kg in a relatively short time too. I know I’m biased because of my personal experience, but still..

Report comment

I mean, I lost that 25 kg in a short time (a year) after going to a low carb diet. I admit that I also also tapered down or reduced the drugs during that time, the drugs that caused the weight gain in the fist place. At least in my case, the best solution was to go in a low carb high fat diet. I also started to exercise, etc. Also meditation, etc. Many factors, but I think that in reducing weight, reducing carbs/sugar was essential. I think that maybe drugs such as Zyprexa fuck up the sugar/fat metabolism so that one should avoid carbs even more that usual. ?

Report comment

By the way, I personally started to gain weight rapidly after I was put on neuroleptics. I was perhaps on way to diabetes, there was something wrong with blood glucose levels at the time. However, I also kept gaining weight or at least not losing it while I was tapering or after I had had quit the drugs. I was after changes in diet and exercise that I started to steadily lose that weight. Of course it helped that I was no longer on drugs, but losing that weight didn’t come automatically for me after I quit the drugs.

Report comment

How about developing tolerance then? How likely is it someone on an “anti-psychotic” will not need a constant drug dose increase long-term and will not be able to withdraw safely because of supersensitivity psychosis?

People should not be started on these drugs and if they are it should on low doses and it should be days and not weeks/months/years.

Report comment

My child also gained about 80 pounds in 4 months from antipsychotic medication. I thought he would lose it rapidly -becasue of he had gained it so rapidly – but now after 8 months of being off the drugs he has not. In addition – being fat is the most frequent, repeated theme in his low self esteem. His food cravings changed on the medications – he used to be a great healthy eater and now craves carbs and sugar. Somnetimes the only way to get him out of bed is eating something he likes. He was not sedentary until after being put on all the medications – oh what a vicious, relentless circle. Of course obesity is now adding to decreased energy etc.

Report comment

As I said above, I’m totally biased about this issue, because of my own positive experiences. In any case, what worked for me was to throw away all sugar and carbohydrates that I can (there’s often sugar added in all kinds of food). It’s actually often good to take fats, such as the fats from olive oil, etc. I personally vote for getting energy from fat, and avoiding sugar and carbs as much as possible.

Report comment

There’s a bit controversial book from Gary Taubes – “Good Calories, Bad Calories”. Or, an easier read, “Why We Get Fat”. They explain some basics of this “controversial” issue. In any case, I admit I’m kind of a fan and supporter. Zyprexa and other drugs may cause insulin resistance, the best bet is to restrict all carb and sugar intake, and eat fat instead.

Report comment

First step is to withdraw him from Zyprexa (this one caused binge eating in me and I think this is a common effect) if he’s up to. Slowly of course.

Then the weight loss should follow. The general rule is simple: more exercise, less food and he should eat everything except junk food (the less processed food the better).

Report comment

Sorry, I’ve missed “ow after 8 months of being off the drugs” reading your comment. I must be still sleepy…

Losing weight is always difficult. As I mentioned: get him a balanced diet based mostly on unprocessed foods (fruit, veggies, good quality meat, good fats), don’t reduce the amount of food drastically (yo-yo effect is lethal) and get him to exercise (start qith10-15 minutes per day and increase). The point is – it can’t make him miserable.

Report comment

Some thoughts on obesity effects of Zyprexa and other atypical neuroleptics. I don’t think there’s any kind of consensus on through what exact mechanisms these drugs cause weight gain. One thing is that they may cause binge-eating, or eating too much, or eating of trash food through some mechanism (maybe partly through histamine H1 receptor?). They don’t actually help in practicing exercise, I quit practicing kungfu and reduced other time spent walking or cycling in part because of the “anhedonia” kind, tiring and sedating effects these drugs had on me.

I think that there’s perhaps also some more direct ways these drugs affect our bodies that cause weight gain. It’s perhaps not only that they cause you to eat more and be more sedentary. There are articles out there which suggest that drugs such as Zyprexa may cause more direct changes in stuff such as in fat/glucose metabolism. See for instance this arcticle from the blogger Last Psychiatrist and the study it references:

http://thelastpsychiatrist.com/2010/10/zyprexa_and_fat.html

Zyprexa caused the body of mice to utilise fat preferentially, which resulted in elevated glucose and insulin levels. Elevated glucose and insulin levels may lead to insulin resistance and metabolic syndrom.

Other article: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24100786

“Atypical antipsychotics may “directly” influence glucose homeostasis, increasing risk of type 2 diabetes independently of changes in adiposity. “

I personally don’t think weight gain and loss is only just a “calories in, calories out” issue. The quality of food can have great effect. Perhaps with drugs such as Zyprexa, it’s especially important to be careful of the sugar and carb intake? Many people in modern world get huge amounts of carbs and sugar through bread, pasta, pizza, all kinds of food you find in supermarkets and so on. It’s perhaps not a very helpful combination with drugs such as Zyprexa which perhaps have quite severe effects on glucose and fat metabolism.

Report comment

Hi Sandra,

I know this is a late reply, but I saw your APA article and I had a few questions about your data here.

First, of the 32 people that originally started tapering, it appears that only 5 continued or finished with that tapering process as of 2014. That would leave 27 (85%) of the original group who either were hospitalized (7), died (2), left your counseling (4), decided to stop abruptly (1), or stopped the tapering process (13). It that is the case, it certainly appears that even slow tapering is a very difficult process.

Second, have any of the original 32 tapered to no medications as all, and stayed relapse free for over a year?

I think this is important, because we know that roughly 80% of people will relapse if they come of meds abruptly, but maybe people with slow tapering are not hospitalized as often because (1) they are still medicated enough to hold their disorder intact, and (2) when they start to feel anomalous experiences coming, they are more likely to raise their medication level on their own – hence the 13 people who quit tapering.

Thank you for your efforts!

Sean Blackwell

bipolarORwakingUP.com

Report comment