I learned of the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians in 2001 through the paper, “Wild Indians,” by psychiatric survivor and activist Pemina Yellow Bird (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Akira Nation). Pemina movingly described the notorious history of this federal facility which operated from 1899 to 1933 alongside efforts to honor the 131 graves situated in the middle of a ‘no play zone’ of the Hiawatha Golf Course in Canton, South Dakota – literally, the Asylum’s last remains.

At the time I was reading it, I’d been thoroughly rejected for my views by fellow ‘providers’ at the Yakama Indian Health Service (IHS) Clinic’s ‘Mental Health Department’ (there was a large red sign no one would sit below). I had no prior experience with such rancor and often sat isolated between meeting with clients and families in a dimly-lit exam room converted to an office on the ‘Indian side.’

There are fictional correlates to my struggles with IHS at that time, in the character of curmudgeon psychologist Dr. Ret Barlow (seen in Tessa’s Dance and Signal Peak). Like Ret, I’d been socially-segregated away from the more appealing, windowed spaces of my colleagues down the hall. I was fine with my locale, but I needed friends.

When I finished reading, I searched up Pemina’s email address, and we began a series of lengthy virtual exchanges that helped galvanize my spirit through the many emerging battles with IHS’s psychiatric labeling and medicating approach to treating Yakama reactions to oppression, and the related psychosocial stress.

In short, I began to fight back, and I am grateful to Pemina Yellow Bird for helping me to stay true to my beliefs in those days. Washi Taherere.

But I took my lumps. Retreating to Yakamart after one of several Friday late-day performance appraisals by the IHS medical director (designed to ruin my weekend), I finally struck up a friendship with a local Blackfoot elder named Long Standing Bear Chief (English name, Harold Gray).

He was a radical Indian, an AIM sympathizer, an author, publisher, cultural authority, and graduate educator, the first director of Indian Studies at the University of Montana. I feel very fortunate to have known him. Whenever I had questions, I ‘brought tobacco’ for my elder’s pipe and we began our consultations or entered the sweatlodge to consider. We laughed a lot too. He had a lengthy history of advocacy for Indian people, and right up to his passing in 2010, he encouraged me to do all I could to expose the intergenerational effects of the mental health movement’s oppression of American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Unavoidable circumstances forced my departure from the area in 2006, and while I continued to consult with Yakama Nation, I became an associate professor at a (now-defunct) doctoral program in Seattle. Before Washington School of Professional Psychology got bought out by an unscrupulous for-profit college and gradually ruined, there happened to be a little yearly stipend for ‘faculty development.’

I decided to use my stipend to do some research on the Indian Asylum

Beyond Pemina’s paper and an apologist-toned history dissertation on the subject, there wasn’t much out there. There was even a belief that actual clinical records for Asylum inmates had not survived its closure. But I ran across good evidence that this might not be altogether true, and at least some of the files might still be divvied up between various locations of the National Archives Records Administration (NARA).

I decided to use my stipend to travel to the National Archives at Fort Worth, Texas.

I flew down by myself and brought along my old scanner because NARA doesn’t allow you to make photocopies. I eventually found the place and drove a rental car along an entrance road past hundreds of unused, polluted FEMA modulars once intended for Katrina survivors, and past many, many lettered buildings to the one I was seeking.

There, I met a dowdy but friendly elderly woman quite pleased to actually have a visitor. She was, however, insistent on adherence to protocol and directed me first to apply for a National Archives research card, which she thereby approved and fashioned. She passed it over to me for inspection, and I then passed the card back to her by way of asking to see materials.

A lot of time passed before she finally labored through the door with a cart holding several beat up ancient boxes. As I looked what was inside over, I began scanning in a crazed frenzy, uncertain whether I’d have enough time in the remaining single day I had in Fort Worth.

A few minutes later, she came up to my side to watch what I was doing. It was quite all right with her; she just didn’t have much else to do.

“Would you like to see the archived court materials on Indian Lunacy determinations?” she asked me lazily.

Three large boxes followed. I continued to scan, beginning to break a sweat.

I still have all of this material – but I know there’s more to be acquired at other locations, squirreled away, misfiled or mislabeled, purposely misplaced? It’s out there.

In trying to understand what these ancestors would tell us, we have to dig. And why wouldn’t the federal government want to make it easier?

Let’s leave aside for a moment the significant number of American Indian WWI veterans I mentioned in my last blog post, surging the population at the Indian Asylum after they returned – many of them preselected for exposure to front-line combat by the Alpha-Beta tests of early psychologists.

Let’s refrain from looking closer at the graves on the golf course, and the filthy coal-fired furnaces that coated the floors with soot that caused chronic respiratory diseases and the deaths of so many resistors forcibly committed to the Asylum for refusing to surrender their children to boarding schools, give up their land to informed speculators, or otherwise accept the domination exerted by federal or church authorities.

We’ll turn back from the children born and buried there and avoid touching upon the scandalous discovery by white investigators in 1933 of so many ‘sane’ Indian people shackled to beds and pipes, keys to their locks lost, and in chains so tight as to make them difficult to saw off. We’ll close our ears to the death songs echoing in those hallways.

And instead, let’s focus on the embarrassing psychiatric diagnosis Alvin Abner Big Man with Horse Stealing Mania.

It’s not in our current DSM-5 because it’s evidently become more rare since then.

The statute of limitations for discussing archival medical record is 75 years, so I’m legally allowed to share with you his case, although his name’s a pseudonym because I have concerns about troubling his descendants.

Alvin Abner Big Man was Lakota, and a ‘reservation policeman’ from Rosebud Reservation. He was first diagnosed with Horse-Stealing Mania by the reservation agent, Charles Davis, after he refused to plead guilty to stealing horses. Mr. Davis suggested that Alvin’s “erratic behavior” in jail made him better suited for an institution for the insane. In 1913, Alvin was forcibly committed to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC. He’s described in St. Elizabeth’s records as “uniformly good and free from any gross disorder.”

However, the doctors at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital were not entirely confident in the Horse Stealing Mania diagnosis, and so they agreed to continue housing Alvin only temporarily. They couldn’t think of a better diagnosis and decided to write to the Indian Commissioners that: “in view of our inability to definitely come to a conclusion about this man, on account of the conflicting stories in the case, we would suggest that he be transferred to an institution near his home.” Such was the conscientiousness back then that the St. Elizabeth’s psychiatrists wanted Alvin off their caseload.

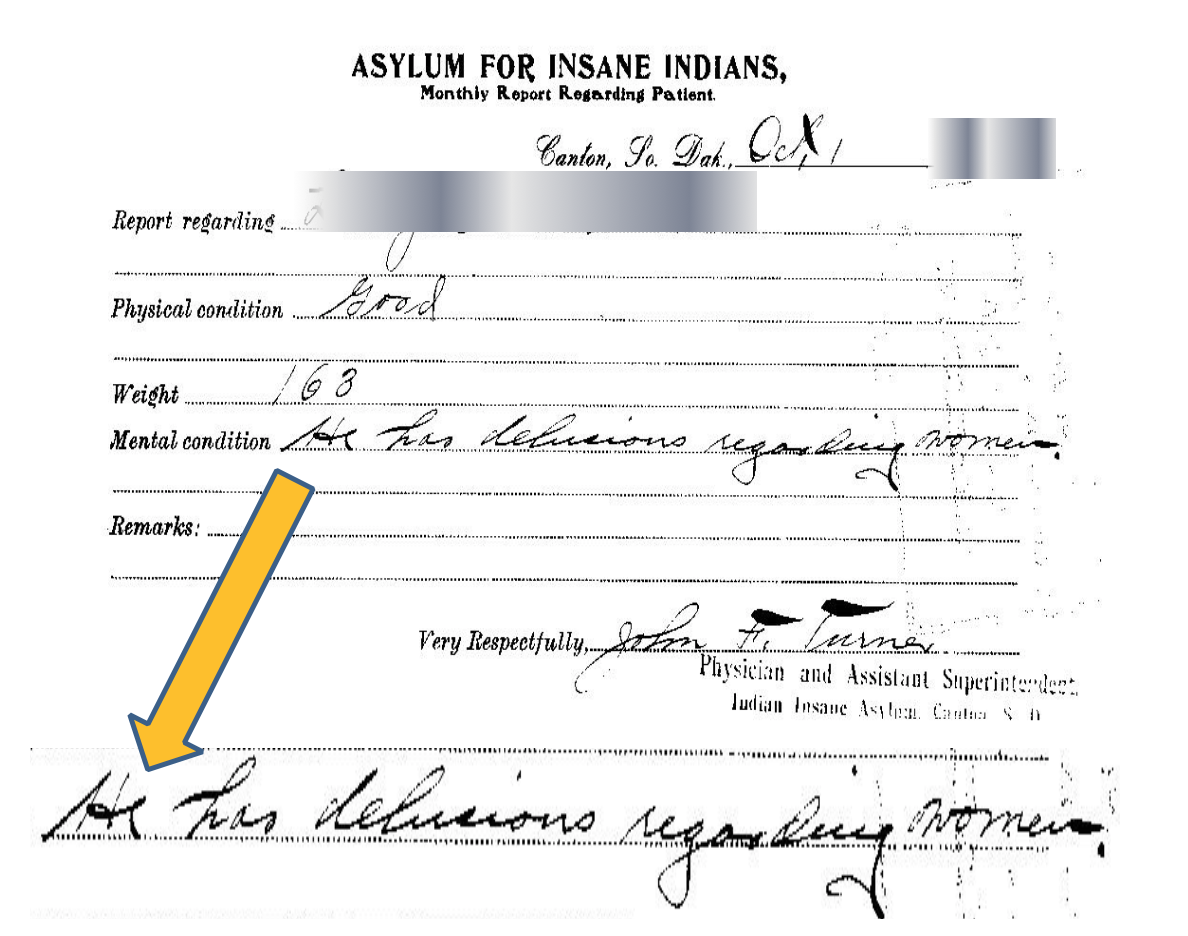

So in 1916, Alvin was transferred to the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians. He was examined by its superintendent, Dr. Harry Hummer, with Constitutional Inferiority. This label may sound obscure but Alvin was seen as apparently having a penchant for communicating amorously toward women at the Asylum, and he was violating eugenics-based rules forbidding fraternization between the sexes:

Otherwise, Alvin was reported to spend much of his time beading and helping others.

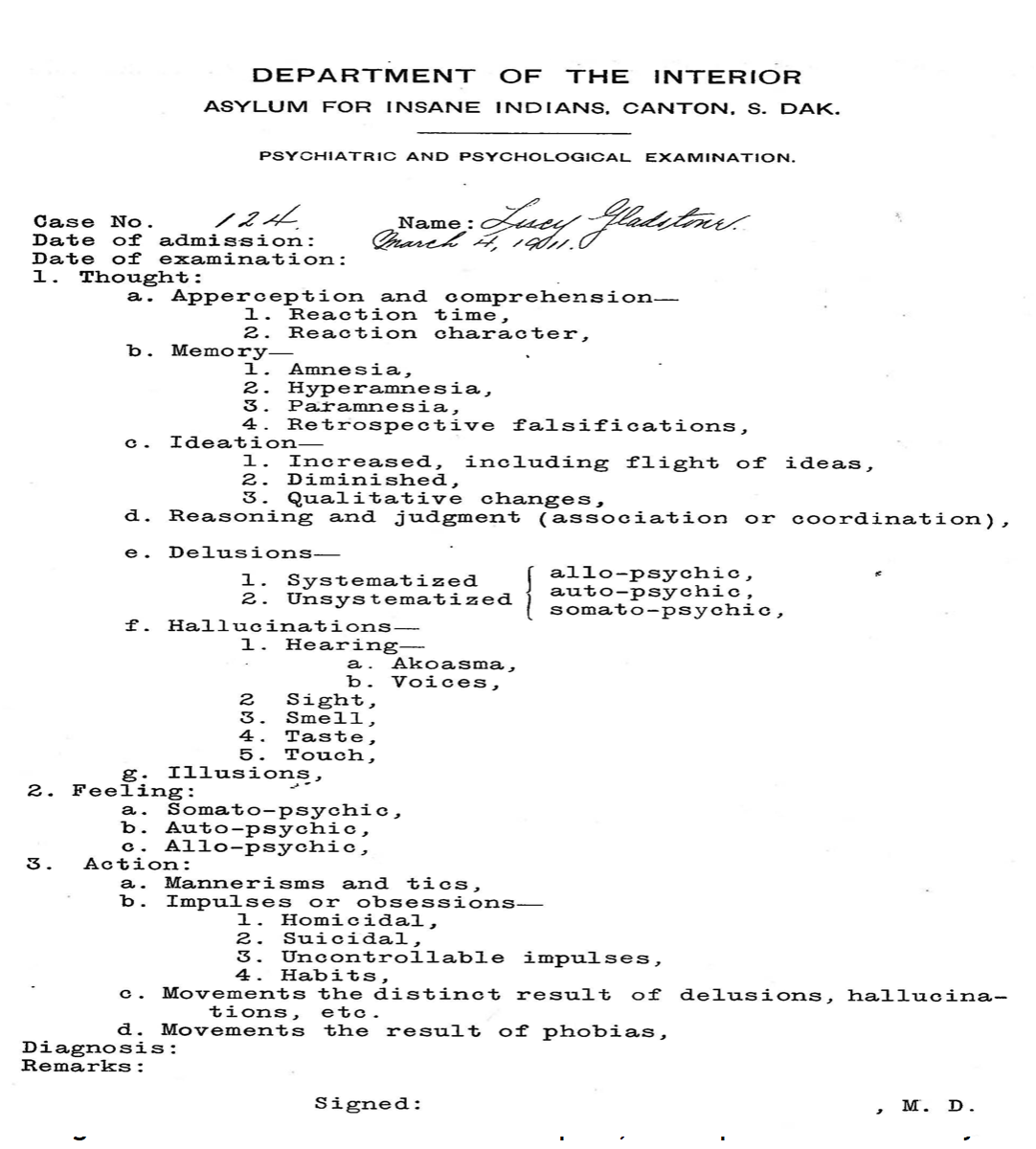

Further evaluation was undertaken using a mental status examination format not so different from the current one stipulated in the contemporary Patient Assessment section of the Behavioral Health Manual of the Indian Health Service. Check it out:

After being transferred from St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Alvin spent the next two years in the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians, pleading through his attorney and via other means to somehow be released. His federally-funded ‘treatment’ for Horse Stealing Mania took place over a period of nearly five years of incarceration.

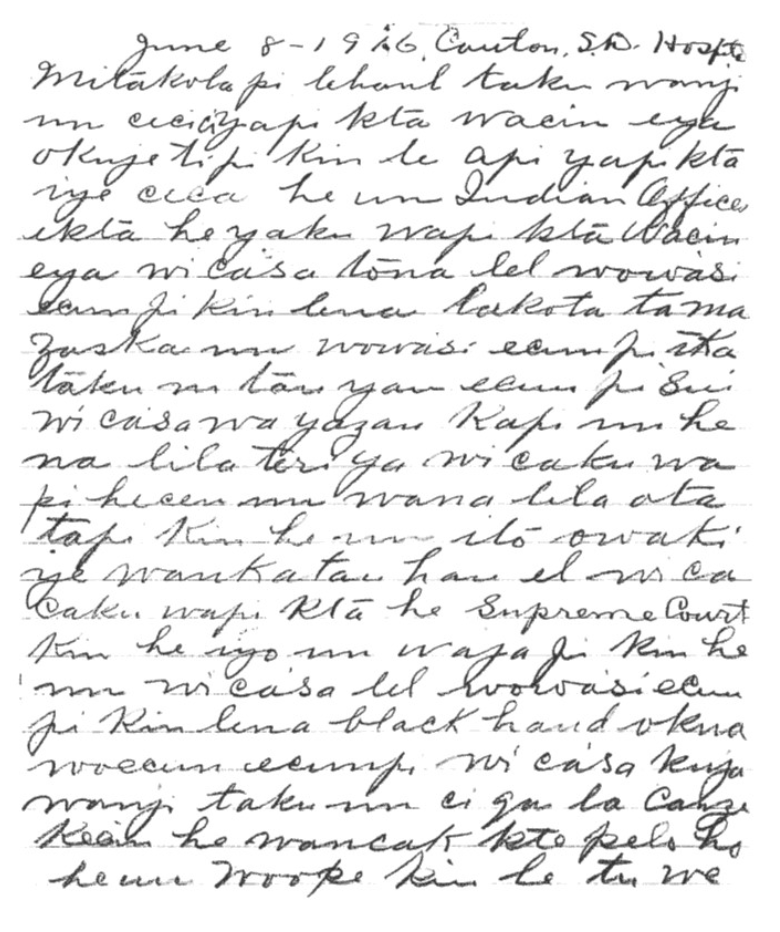

Fortunately for us, Alvin turned into an in-house activist, fighting against the lead psychiatrist, Dr. Hummer about the treatment of his fellow inmates. I’d say he became rather a thorn in the Doctor’s side. He even attempted to smuggle a note out of the building to the Indian Commissioners to let them know what he was observing:

It was clever of him to write this in phonetic Lakota. However, Dr. Hummer was one step ahead. He intercepted the note and had it translated:

“fix no building, employers paid but don’t do right, make sick people work, many of them die, wants take employers to Supreme Court, Entitled to use Supreme Court, employers using ‘Black Hand,’ sick persons do anything, could get mad & kill them, Take these men before Grand Jury, find these white people guilty, that’s why I told this, we are starving, have an inspector to come, want to talk to him, using us rough, wants them to copy this letter in English, wants them to use Commissioner of Indian Affairs to help”

I found both Alvin’s note and this translation in his medical file. I don’t know if the note ever made it out of the building. As to ‘Black Hand’ to which Alvin makes reference, if you do a little research, you’ll discover that this was a common term used by the news media of that time to describe an extortion technique in the early days of organized crime.

Shortly after this note was written, Alvin was released by Dr. Hummer. Apparently, treatment of his Horse Stealing Mania had been a complete success.

The Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians continued on for another 17 years, finally being closed in 1933 after the (not) surprising discovery that it housed many ‘sane’ native people like Alvin. These ‘sane’ Indians were released. However, those inmates deemed as still of significant concern were sent off to no other place than St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, DC.

At the time of the transfer of the Indian Asylum inmates to St. Elizabeth’s, Walter Freeman II, MD was director of services at its Blackburn Lab. He left for Georgetown University in 1935 and performed the first lobotomy in the United States in 1936, gradually perfecting his famous ‘ice-pick’ (trans-orbital lobotomy In 1943, Dr. Freeman recommended lobotomies as the ‘treatment’ of choice for veterans suffering from the after-effects of war exposure. He was selected by the Kennedy family to apply his techniques to JFK’s sister, Rosemary.

I haven’t yet been able to discern if Dr. Freeman had a chance to utilize any of his new techniques with the inmates transferred from the Hiawatha Asylum for Insane Indians after it was closed down.

I’m glad to report Alvin made it out long before all that. I was very grateful to have eventually found his note.

David Walker, thank you so much, both for calling attention to the ground-breaking work of Pemina Yellowbird, and the vital work that you did in the archives to document the treatment of Native Americans by the psychiatric system. Documenting the history of institutionalized psychiatry in America is a crucial undertaking – so many thousands of people’s lives were literally stolen from them. And the powers that be would like to sweep all that under the rug as if it weren’t still happening in a way that differs more in style than in substance from the horrors of the past.

Report comment

Yes, Darby, I agree. The restraints are chemical instead of leather, and the asylums are the ‘forced hospitalizations’ and ‘court-ordered treatments’ cloaking tyranny beneath the guise of benevolence. Thanks for your comment.

Report comment

Word play that makes Orwell shy. It’s as much “hospitalization” as “anal feeding” is medical treatment. They need to change the words once in a while so the slower or not so well informed people get confused. Torture is torture by any name.

Report comment

Very moving, and as Darby says, so true even now.

Report comment

Thanks for your support, Ted!

Report comment

Great research— very interesting and necessary to help fill a large void in U.S. history and the lives of Native Americans.

Report comment

Thanks for your comment wileywitch. My hope is to gradually move the range of inquiry to indigenous people worldwide because I hear these sorts of things have gone on in many communities.

Report comment

I’m hoping a book is in the making from this– both about your professional subjugation (found myself wanting to know the blow-by-blow, tones of voice, the characters doling it out) as well as the fleshing out of what you found in archives. I think it will highlight the work already done by Yellowfeather and maybe add the twist that the same thing is now decimating the culture at large. It’s got an essence of biblical irony when it happens to middle class white people, but it comes with increased oppression to everyone else.

As another commenter mentioned, it’s still happening. I think it’s come back hungrier than ever.

As a parent of young children, the way I feel it the most keenly is that, with the privatization of child welfare, these agencies and mainstream medicine seems to be using bad psychiatric theory as a tool of enforcement for various industries, not only to force consumers to the trough but to kill any opposition to industrial policy.

I won’t get into too much detail about it– the stories of children being taken away from their homes on increasingly thin pretexts are all over the web and documented on various sites like Medicalkidnap. But it should be familiar. We keep seeing strange new diagnoses crop up criminalizing parenthood in many different ways. And what I keep sensing is that, on top of being perversely incentivized, this is genuinely a form of “politicide”– an attempt to snuff the formation of a political culture in the US which threatens control of consumerism through a new form of psychotic social engineering. Anyone looking closely at the cases would start to notice the common threads– families that dare to eschew commercial products or threaten to supplant these products with safer alternatives or whose lifestyles speak of a kind of anti-consumerism, or who threaten to expose toxic fallout from deregulation. For each insane state kidnapping case, there is an industry, usually those sponsoring hospitals and CME, whose ox is getting gored in some way.

In short, we let Native children be taken wholesale by the state and now everyone’s children are in the cross hairs. Obviously the analogy goes further than this with the increase in forced institutionalization, court ordered drugging and police shootings of the mentally ill, etc. So I think it’s time we know every gruesome way this was carried out against Native peoples in its heyday, both to honor the victims and wake people up.

Report comment

Thanks so much for your comment and analysis, Crux. Many children and youth are being socialized these days to believe the labels and meds that paint them as damaged, inferior, or otherwise dysfunctional, instead of containing infinite possibilities within their nonconformity, difference, and awkward genius. BTW, the ordeals of curmudgeon psychologist Dr. Ret Barlow in my two indie novels (www.tessasdance.com) contain numerous parallels to my own professional subjugation. Even so, I must assure you that they are both entirely ‘works of fiction.’

Report comment

David ,

You remind us again how fortunate we are to have you blogging here at MIA. In the history you show us we can see our present and future . There seems to be no grand escape only the option to stand and fight as warriors against the oppressors.

Fred

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Fred. It is I who am fortunate to blog on MIA. From what I’ve been learning, I’ve concluded that we all contain the seeds of future oppression and our own liberation is the best fight we have against it.

Report comment

I also always enjoy reading about your research and ideas, David. Thank you. My own story includes a note of heartbreak for the “Redskins,” because of the deplorable things the white men did to them. As I think I mentioned to you earlier my cousins are part native American, and one of my cousins is so disheartened by the white American small banking side of our family. If you happen to have any advice for writing a true and well researched story as a “credible fictional story,” I’d be grateful for the advice.

Report comment

Thanks for your comment, Someone Else. My novels started as a nonfiction project. However, I came to feel no one would believe me. It is interesting to change the names and attributes of characters, combining them until they’re unrecognizable in relation to your own lived experience, build a plot that approximates some of what you’ve heard, some of what you’ve known, and some of what you’ve lived, and then find the fictional end result becomes more believable. I hope that helps.

Report comment

I’m not certain it does. Because I have no desire to change the names or characteristics of the guilty, they’re all relevant to the story. I merely want to change the names of the innocent, except myself. I don’t actually agree with the doctors who claimed my entire life to be a “credible fictional story” in my medical records. I still believe I’m a non-fictional person.

And it strikes me that since doctors claimed my entire life, and all humans within it, to be “fictional” within my medical records; and they did not repent when given medical and actual evidence to the contrary. They’ve taken legal liability for their diagnoses and claims.

I know I’ll need to hire a lawyer prior to publishing my story, since it’s a story about medical malpractice and religious crimes against my family. But I do think it’s important to expose what was confessed to me, by an ethical pastor of a different religion, to be “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions.” The medical community and the religions need to stop utilizing the psychiatric industry to defame, discredit, and torture those who’ve dealt with prior easily recognized iatrogenesis and child abuse.

This was not the story I chose for my artwork to tell, it’s one God chose for me to tell. And I believe it is because these crimes against humanity by the mainstream medical, religious, and psychiatric industry need to end. The mere existence of unprovable “mental illnesses” allow the unethical in charge to destroy anyone they please. This is not in the best interest of humanity or justice for all.

Report comment

I think I didn’t understand your question or your quest, someone else, and I hope you prevail. In my own situation, fiction ‘worked’ better to keep the story I needed to tell off some dusty shelf in academia. Nonetheless, I began the process by writing about what I’d seen and experienced directly and was warned quite vehemently that I’d be sued. It is one thing to tell the truth, but quite another to be threatened with having it obscured and re-spun in a manner that would hurt one’s career and family. Fiction offered not so much a retreat as a means of expanding an audience for the issues I felt were more important than my own particular situation. I wish you justice in your own efforts.

Report comment

Dr. Walker:

Thank you for sharing this. Your personal observations and your strong conviction reinforces my desire to view our daughter’s ‘mental illness’ through the lens of our family’s heritage and the courage to pursue healing at least in part through an understanding of what our ancestors experienced. Not sure who we will meet and what resources and provisions are required for this journey our family is on, but I have faith that we will meet the right teachers when we are ready. And maybe when our family experiences a profound healing (as defined by understanding and widsom) we will have something to give back to this community.

Report comment

Thanks so much for your comment, madmom. I’m very glad that you are looking at what’s going on with your daughter in light of family history. I’m currently writing a fiction project partially based on the life of my own grandfather, who enlisted as a regimental runner in the Army at the age of 16 and was ‘invalided’ out due to being gassed at age 18. I believe the pain of what he went through in the Vosges Mountains in 1918 crossed three generations beyond him.

Report comment

Great and important research.

What we (the white people) did to Native Americans (and other colonized people), the genocide, the enslavement, the destruction of culture, the stealth of land… it’s so deplorable. And then we decided to label you as “mentally ill”. There is a never ending cycle of insult to injury to insult… I’m ashamed of my race.

Report comment