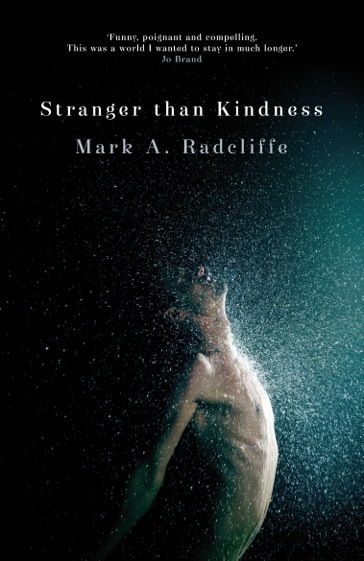

A couple of years ago I had a novel called Stranger Than Kindness published in the UK. It was about the cumulative trauma that can accompany work in the caring profession; how people can become bruised and reshaped by caring for a living, and what they might do to repair themselves. It was essentially a comic novel about hurt nurses.

The first half of the book was set in an old Victorian asylum, at the end of the 1980’s, as it was closing down and discharging its last two hundred patients into a community that was not exactly lining the streets with bunting by way of welcome. It was a hospital that bore close resemblance to the one I trained in.

The first half of the book was set in an old Victorian asylum, at the end of the 1980’s, as it was closing down and discharging its last two hundred patients into a community that was not exactly lining the streets with bunting by way of welcome. It was a hospital that bore close resemblance to the one I trained in.

The second half of the book takes place twenty five years later and reunites the nurses in a struggle with ‘Bad Pharma’ and a couple of stop-at-nothing careerists who help oil that particular machine, one of whom happens to be a psychologist.

When promoting the book I found myself talking to two different audiences. The first, were people who like books and come along to events and chat about them. They were interested in stories and whatever world they happen to emerge from. The second were occupied by people with a special interest or expertise in mental health. I found the questions asked and the conversations that we had were different in those two spaces.

For people outside of the mental health system the book described something they have heard about, may be interested in but are not particularly familiar with. Consequently questions were broad; ‘Are those patients real?’ ‘Did people really believe they didn’t have a body?’ Or ‘Is the messed up bloke who keeps getting in the sea to swim based on you?’

Inevitably the discussions were different among people with mental health expertise. Not hostile or challenging but there was often a sense that it was their world that was being represented and as such it needed to be interrogated or, more often, celebrated.

There were a couple of things that came up a lot. The first was why, when you are gazing into a Victorian lunatic asylum, would you turn your sympathy toward the nurses? And secondly, what on earth have you got against psychologists?

The first one is easy. I was a nurse and I am interested in the underpinning humanity of nursing. I like literature that turns its attention to people who are traditionally minor characters in other people’s novels (I teach nurses now and I often tell them that a good nurse writes themselves well in their patient’s stories) Also I am interested in the stories of characters who are traditionally marginalised (there are an awful lot of books about madness, not so many about the people who sit beside it). I’m also interested in emotionality in an age that worships reason, and in wisdom in a time that prioritises knowledge. I think caring thoughtfully is a pursuit of wisdom and I was curious about what that looked like or felt like or demanded.

As for Psychology, well it seems to me the most interesting thing about psychology (and perhaps this can be said of many liberal institutions?) is how hard it works to make sure everything stays the same whilst at the same time presenting itself to the world as the progressive and liberal minded Bobby Ewing to medicines’ big-hatted JR.

That is not to say there isn’t brilliance among psychologists, but as an industry psychology has become a coloniser. It lays claim to any emerging philosophical or clinical movement, in part because it thinks that is the morally right thing to do but also, I fear, because psychology believes in itself as a science to such an extent that it seems no idea, movement, approach or thought can be validated without the benefit of its ‘method.’ Oh; and also I fear it realises that if it oversees everything from broad therapeutics to “Recovery” to “Mindfulness,” then it expands as an industry.

The appearance in the UK of Mindfulness offers an example. Mindfulness emerged in mental health services from an interest in the therapeutic benefits of meditative Buddhist practice. What was interesting about it was the extent to which it enthused practitioners and service users alike with its apparent simplicity. What struck me as interesting about it was the fact that it was quiet. To a backdrop of psychiatric chatter; from diagnosis to assessment to formulation to therapy, so much constant unyielding noise, came something helpful and nearly silent.

The first close contact I had with Mindfulness was in the very early 2000’s. I was leading a Post Graduate Mental Health Practitioner programme and one of the students had started exploring Mindfulness in her practice with another clinician and a few curious patients. She was enthused, engaged, and it appeared to be useful. Within a few weeks she had been told she had to stop. She was not the appropriate person to be doing Mindfulness. I assumed the ward was brimming with better qualified appropriately dressed monks, but no, a psychologist was taking over; stand aside, I’m a psychologist, let me through, no I am not trained in this, no I have no natural philosophical or clinical affiliation with this and no until someone told me about it I had no idea what it was, but if it is to catch on it needs psychology and if Mindfulness makes mental health practice look more human, quieter, less brutal, well then psychology needs it.

Does that sound petulant? Ungenerous? It doesn’t matter I don’t think. Psychology can take the gentle bleating of the likes of me. It is flourishing, it is an institution, it is the self-appointed flagship for humanistic mental health care and that is not a wholly bad thing because if nothing else that expression of humanism slows down some of the more mechanistic and brutalising manifestations of psychiatric services. But it is how it functions as an industry or ideology that unnerves me.

Psychology has earned itself power within mental health. Indeed the perpetual negotiation between psychology and psychiatry dominates services; talking therapy and medical intervention are a marriage of balanced, civilising science. But I think that means that anything new, challenging, enquiring or simply not existing within the voracious remit psychology gives itself becomes devalued.

Indeed, it means that anything without an ‘evidence base’ is marginalised, even though mental health services would make no sense without ‘unevidenced activity’. We spend our time offering simple one-to-one time or being alongside people when they are in crisis, or sharing simple community or group activity or facilitating a capacity to do ordinary things and we do them because we ‘know’ they help. But they have no substantive evidence base.

Consequently ordinary activities which are therapeutic or beneficial are diminished both in terms of clinical value and in terms of economic investment. ‘Evidence’ elevates certain activities or skills or professions, and in so doing establishes and reinforces a hierarchy of interventions and knowledge that constructs services, and worse, the very reasoning services are founded on. And so the scramble to lay claim to things which offer a potential for evidence and more power is a driver for service development and of course nothing anyone can say will change that.

In Stranger Than Kindness a drug company funds some research that compares the effectiveness of an expensive anti-psychotic with a communal therapy called ‘Context and Cognition Therapy’ or CCT. CCT is wholly made up of course and comprises little more than sanctuary, extended kindness and the facilitation of meaningful activity that is educational and enthusing. It treats illness as circumstantial and the desire to engage with something as akin to what Marx (in his early years) described as ‘Species Being’, IE; we are driven to act productively in the world in some way because that is what being human demands. It was as far from psychology as one could get and perhaps more importantly would be too costly and ridiculous to ever consider viable. It was whimsical and playful and (in the book) emerged by accident, but whilst in the novel it was threatening because evidence emerged to say it had better results than drugs and CBT, in reality such possibilities would never be explored because; a) it is not economically viable to set up well-staffed mental health sanctuaries that offered such things, b) thinking beyond medication or psychological therapies is not ideologically available to us and, c) it would threaten too many other existing markets (pharmaceuticals, CBT training)

And I don’t think that will change. I think that the professions or industries that hold power hold it in such a way as to be able to define the terms on which power is constructed and shared. They are self-perpetuating. I think that that is why I have come increasingly to think of psychiatry as industrial and why I have retreated to a world of story making.

I like whimsy. I think it helps us to be human, and it seems to me that no matter what changes mental health services undergo they continue to seek out ways of trying to be more human. It seems to me that it is important that we always ensure that those attempts to be ‘human,’ to engender our services with kindness and respect and decency, are authentic.

Nurses can have a huge impact on an individuals mental wellness. How a service is delivered is critical but even the kindest nurse in the world can not mitigate the harm and impact of conventional practices such as forcing patients to the ground and injecting them by force, what many call needle rape. Until nurses who are in the trenches and see the harmful effects of involuntary treatment stand up in solidarity against restraint, seclusion, institutionalization, and forced injection, the rest is window dressing.

Report comment

YEP agreed.

Report comment

MIA, whoever chose to publish Dr. Radcliffe’s article deserves a pat on the back. This is the first article I’ve read about a jaded clinician’s voluntary, unpretentious, and mutedly accusatory exit from their career in the field of health care. I don’t doubt that Dr. Radcliffe was a top-notch nurse, but shit happens and sometimes people just have to admit that they can no longer deal with it and still provide people with the care they deserve. Thank you, Mr. Radcliffe, for telling us about what psychiatry is like from the perspective of an ex-clinician who bowed out of medicine before they turned bitter, as opposed to after, which, as we all know, is the far more common scenario.

Report comment

Oh this looks hella interesting.

The colonization aspect is something I really want to see more fleshed-out literature around, I remember a friend/mentor of mine describing to me the particular role of psychiatry in forced assimilation of First Nations people in Arizona and New Mexico.

So, stuff on that, plus Early Marx On Species Being? I want to see it.

Report comment

“sanctuary, extended kindness and the facilitation of meaningful activity that is educational and enthusing:” doesn’t sound too far from Soteria House.

That psychiatry holds onto it’s power seems true. I was talking to people about how to deal with a, “Mental health crisis,” on week long retreats and how it might not be wise to call the services and to be aware of what they do and do not offer. The guy was receptive and then said but eventually you need to call the expert.

Most people have faith in the instution even when presented with evidence that it is damaging

Report comment

“Anyone who wants to know the human psyche will learn next to nothing from experimental psychology.

He would be better advised to abandon exact science, put away his scholar’s gown, bid farewell to his study, and wander with human heart through the world.

There, in the horrors of prisons, lunatic asylums and hospitals, in drab suburban pubs, in brothels and gambling-hells, in the salons of the elegant, the Stock Exchanges, socialist meetings, churches, revivalist gatherings and ecstatic sects,

through love and hate,

through the experience of passion in every form in his own body,

he would reap richer stores of knowledge than text-books a foot thick could give him, and he will know how to doctor the sick with a real knowledge of the human soul.”

Carl Jung.

Report comment

Kindness is an inner quality that leads to a very fine mental health professional. Burnout can happen to all mental health professionals and paperwork demands can make it hard to cope. Enjoyed the article and I can learn from your experience.

– Pat

Report comment

because psychology believes in itself as a science to such an extent that it seems no idea, movement, approach or thought can be validated without the benefit of its ‘method.’ Oh; and also I fear it realises that if it oversees everything from broad therapeutics to “Recovery” to “Mindfulness,” then it expands as an industry.

Psychology can seem a continuation of the temperance movement, a special application of the general progressive principle that the “best” people should govern–people qualified, that is, by allegedly disinterested motives and plenty of professional training (Christopher Lasch from the essay, Life in the Therapeutic State, in Women and the Common Life, p.168, 1997). Also discussed in Life… are ideas inspired by Foucualt in The Policing of Families (1997): describing the movement of a new medical morality with doctors seeking women as agents of medical influence in the medical colonization of the family under the guise of humanitarianism which has ironically lead to the increase, not decline of state torture.

The institution of the psy’s interrupt and hyjack people’s stories.

Report comment

Re clinical psychology: ‘…how hard it works to make sure everything stays the same whilst at the same time presenting itself to the world as the progressive and liberal minded’. I think you could just as easily be talking about mental health nursing here Mark. And don’t forget that it’s the Division of Clinical Psychology of the British Psychological Society that have formally stood out against the medicalization of human misery in the last 2 or 3 years, in the form of ‘Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia’ and ‘Time for a Paradigm Shift…’ Mental Health Nurse Academics UK seems one of the most conservative, normative policy-following collectives I’ve come across. This is matched by editorial policy in the Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. Really glad that I’m not part of either any more!

That said, Stranger than Kindness is a great novel!

Report comment