In this month’s issue of the journal Brain a new study investigates whether the drugs prescribed to control seizures can increase the risk of psychotic symptoms in some people. After reviewing over ten years of medical records of patients treated for epilepsy, the researchers concluded that up to one in seven cases of patients with epilepsy who were later diagnosed with psychosis could be attributed to an adverse effect of the anti-epileptic drugs.

“Antiepileptic drug-induced psychotic disorder (AIPD) was common among epilepsy patients who develop psychotic symptoms,” the researchers write. “In our study one in seven patients with epilepsy who presented with psychosis had AIPD.”

It is well established that patients who have epilepsy are at an increased risk for psychiatric symptoms including psychosis. Past research has also demonstrated that the drugs used to treat epilepsy (antiepileptics) can also increase the risk for these symptoms. What is less well understood is what percentage of epileptic patients develop psychiatric symptoms as a result of their medication and how psychiatrists can learn to better recognize antiepileptic-induced psychotic disorder (AIPD).

Hampering efforts to understand the signs of AIPD is the general controversy and disagreement in the field over how precisely to define psychotic ‘disorders’ more broadly, and the lack of a reliable and valid diagnostic system.

“As a result of these limitations in knowledge, the management of AIPD in clinical practice is extremely challenging and not evidence-based,” write the study authors, led by Ziyi Chen, from the University of Melbourne.

“Misdiagnosing AIPD as primary psychotic disorder may lead to inappropriate management, including continuation of the culprit AED and additional treatment with antipsychotic drugs. Often, the psychotic symptoms of AIPD persist in a fluctuating manner as long as the AED is continued. The patient may endure both the adverse effects of the AED and potential exacerbation of epilepsy by antipsychotic drug therapy.”

This latest study attempted to bring some clarity to this issue by investigating the case reports of patients with epilepsy who developed psychosis and comparing those who took antiepileptic drugs and those who did not. The researchers reviewed the records of 2,630 patients who were treated between 1993 and 2015 at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia.

The study found that 5.6% of all patients with epilepsy developed AIPD and that one in seven patients with epilepsy who experience psychosis are experiencing an adverse reaction to their seizure medication. In this study, females appeared to be at a higher risk than males for AIPD, with almost 2/3 of all AIPD cases being women. Also, those with specifically temporal lobe epilepsy appeared to be at a higher risk.

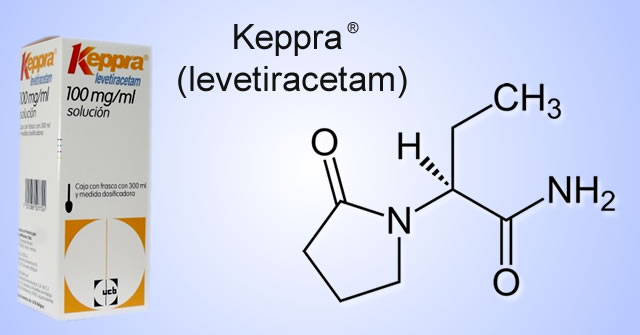

Certain antiepileptic drugs carried an increased risk for AIPD. According to the study, the drug levetiracetam (Keppra, Elepsia) was most commonly associated with AIPD, leading the researchers to warn that “when a patient with epilepsy presents with psychotic symptoms current usage of levetiracetam should raise the strong suspicion of AIPD.” Meanwhile, the drug carbamazepine was negatively associated with AIPD, suggesting it “might be a safe substitution for the offending agent.”

While patients with AIPD did not have more hallucinations or delusions than epileptic patients experiencing psychosis who did not take antiepileptics, those with AIPD did show more disorganized thinking and abnormal behaviors.

Interestingly, the study data did not indicate that AIPD was more common when higher doses of the drugs were used or when patients had been more rapidly tapered off of a drug. The researchers suggest that individual differences in the metabolism of the antiepileptic drugs may play a role in the increased risk for AIPD.

****

Chen, Z., Lusicic, A., O’Brien, T.J., Velakoulis, D., Adams, S.J. and Kwan, P., 2016. Psychotic disorders induced by antiepileptic drugs in people with epilepsy. Brain, p.aww196. (Abstract)

This reminds me of Karl Pfeiffer’s work. He divided “schizophrenia” into four basic types based on serum histamine: histapenia(low H), pyroluria (“normal” H, but secreting urinary pyrolles), allergics (same?) and histadelia (high H). These groups required different treatment programs, where sometimes things good for one group were bad for the others. One of the drugs used for the histadelics was Dilantin, as part of a histamine lowering program, which might be bad for the histapenics. This may be trivial, but I wonder if there’s something to this with the convulsing patients. If it were true, the subjects would tend to have racing thoughts and a speeded up nature, perhaps up to the edge of mania, few or no allergies or virus diseases, insomnia from racing thoughts.

Report comment

Oops, that should be Carl Pfeiffer.

Report comment

“This may be trivial, but I wonder if there’s something to this with the convulsing patients.”

bcharris, I do not think what you are saying is trivial at all; it is quite insightful. It would be interesting and worthwhile to correlate the drug-induced psychosis with each individual’s histamine status (i.e., were these all low histamine people?). Most histamine dysregulation involves high (not low) histamine, and since only a small minority of people suffered psychosis as a result of the anti-epilepsy drugs, your hypothesis is sound. ..It would be good to know if the people affected were indeed histapenics.

Report comment

The criminal part of this is: that when a long term neuroleptic “treatment” turns into muscle problems: tardive dyskenesia, dystonia, akathisia – the first port of call is anticonvulsants.

This is a double whammy, as the neuroleptics increase sensitivity to “psychosis”. Like pouring petrol on a fire, I reckon. And heaven knows, we can’t stop the neuroleptics, or the “psychosis” might return……

So then MORE neuroleptic drugs are added to “treat” the new psychosis breaking through after the tremors got the anticonvulsants added.

The synergy of polypharmacy is a whole new level of complications that we can’t even begin to understand the long term consequences.

Anticonvulsants are widely used in “bipolar” as “mood stabilizers,” too. Is it any wonder that many “bipolars” – often stimulated by an AD, then “stabilized” with an anticonvulsant – tend to flip into “psychosis”?

Terms in “quotes” are labels, not diagnoses…..

Report comment

This is very interesting, since the second line “drug” if diagnosed with “bi-polar disorder” or a maybe a personality disorder that seems similar is an anti-epileptic “drug” such as Tegretol or Depakote. Being in this alleged condition myself, I had been asked when telling the nurses of my “drugs” at the time if I were suffering from some from of epilepsy. In fact, I remember reading at one time there was speculation that something like “bi-polar disorder” may be related to or a some kind of form of epilepsy. Now, in retrospect, this was probably a reason to “legitamize” prescribing these “drugs” . However, I can tell you purely from my own experience that “psychotic” episodes can and do erupt from these “drugs.” As with other “side-effects”, such as memory loss, tremors and loss of

Identity//self and then made worse in compounded terms by prescribing even stronger, even more addictive drugs such as “benzos” and anti-psychotics. I always remember growing up how we were told that if we started smoking marijuana, we would end up on the “hard” drugs like heroin, etc and life would be “unbearable.” This is what happens in psychiatry today. And, most of us at the time are/were “willing victims.” believing like that “proverbial character” in the Television drama of the day that one pill or one smoke will make it “all better.” But, it really does make it all worse. Thank you.

Report comment

Large doses of anti-epilepsy drugs such as Epilim are a very popular feature of the first episode psychosis “movement” drug algorithms. They continue to be marketed as “mood stabilisers” tho there is no evidence at all that such a thing exists or is required. how fascinating but very sad that maybe they cause psychosis.

Report comment