Tineke Abma and colleagues, from the VU University Medical Centre in Amsterdam, write on the social impact of Participatory Bioethics Research. In the recent article published in a special issue of Bioethics, the authors describe how a participatory action approach can be used in bioethics research. As a case example, they describe how they used participatory action to reduce coercion and seclusion in psychiatric treatment in The Netherlands.

“[Social] impact means more than communicating research findings and delivering a ‘product’ or ‘service’ to society, it involves fostering social change within the wider complex social system in which the research is taking place,” write the authors.

Participatory bioethics research emerged in response to the limitations of traditional research methods that prize professional knowledge over those with lived experience. In participatory research, researchers and stakeholders are co-producers of knowledge and there is a specific intent to give voice to marginalized populations. The authors write, “leaving out minority voices and stakeholder perspectives who are less powerful leads to a situation of ‘epistemic injustice.’” Recently there have been a number of calls for more participatory frameworks in research. The authors describe:

“Multiple stakeholders and interested partners are engaged throughout the whole research process, including the framing of ideas and research questions, so that outcomes are tailored to these interests and context, and the type of impact stakeholders envisage. There is an emphasis on realizing social change through the conduct (not merely the results) of the research.”

The basis of participatory bioethics research is establishing trusting relationships between researchers and stakeholders. The authors note, “Besides critical awareness of power relations and social hierarchies, evaluating a moral practice also requires care. Care is a central value in PBR [participatory bioethics research], and understood in the broad sense of nurturing, being attentive to and taking care of important values in life.”

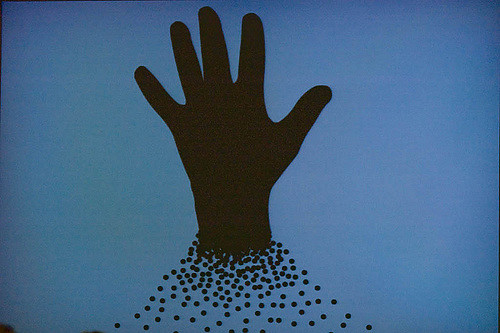

Participatory action approaches have not been widely used in the field of bioethics. The authors seek to outline how this framework can be used to improve the social impact of bioethics research. They use coercion in psychiatry as a case example. The authors define coercion as “restricting the patient’s1 freedom, without allowing him or her any choice.” They identify seclusion—placing a person in a locked room to prevent harm to oneself or others—as a common coercive practice. In The Netherlands, there has been a push in the last two decades to reduce the use of seclusion. The authors describe how they were involved in participatory bioethics research over this time to aid six mental health care institutions in achieving this goal.

In collaboration patients, family, providers, and administrators, the authors developed quality criteria to review when considering coercive interventions. Examples of the criteria include “Use of coercion requires proper communication. Pay attention to contact, openness and staying in touch” and “Be aware of the variety of measures. Do not use more restrictive measures than is necessary.”

The authors also engaged in case studies on particular interventions that could reduce how often seclusion is used. Interventions included things like prioritizing building a rapport from the patient’s first encounter upon admission and having a ‘crisis card’ that describes how a patient would like to be treated in future moments of crisis. In addition, changes were made to the physical structure of psychiatric units, including more comfortable rooms, open nursing desks, and space for family members. The authors note that reducing coercion is not solely about demonstrating measurable outcomes (e.g., seclusion rates), but making larger cultural changes within an institution. They highlight:

“We drew attention to aspects of value and culture, clarifying that developing interventions is not a technical issue. The core of interventions aiming at reduction of coercion and seclusion is providing care, based on values like contact, engagement, responsibility, cooperation and responsiveness.”

The authors note that they are not the experts and cannot determine the social impact of these interventions. Rather, stakeholders need to be the ones to define social impact. In addition, “what counts as impact cannot be stated and planned at the beginning, but emerges in a non-linear fashion over time in conversation with all stakeholders.” Therefore, participatory action frameworks are highly time consuming, as the researchers are describing changes made over decades of collaboration.

The authors write, “By engendering reflection and dialogue in practice, participatory bioethics researchers can help practitioners to find ways to deal with moral issues and improve the quality of care.” An increase in participatory action frameworks in medical and social research could enhance healthcare and improve well-being for service users.

**

1The authors make the following note on the use of the term ‘patient’: “We use here the term ‘patient’, but it is important to note that within Dutch psychiatry some people with psychiatric problems like to identify themselves as ‘clients’ and not as ‘patients’, because they feel the latter term places them in a passive position as mere receivers of care. We agree that it is an important right to be able to identify yourself as you like.”

****

ma, T. A., Voskes, Y., & Widdershoven, G. (2017). Participatory bioethics research and its social impact: The case of coercion reduction in psychiatry. Bioethics, 31(2), 144-152. doi:10.1111/bioe.12319 (Link)