A new study, led by Kathryn Holland, assistant professor at the University of Michigan, examines university policies for reporting sexual assault. Results of the study, published in The American Psychologist, show that the majority of universities require all or most employees to report student disclosures of sexual assault. The authors question common assumptions about mandated reporting policies and also offer survivor-centered reforms.

“A review of the literature reveals limited research to support assumptions regarding the benefits of compelled disclosure,” the authors write. “In fact, some evidence suggests that these mandates may carry negative consequences: silencing and disempowering survivors, complicating employees’ jobs, and prioritizing legal liability over student welfare.”

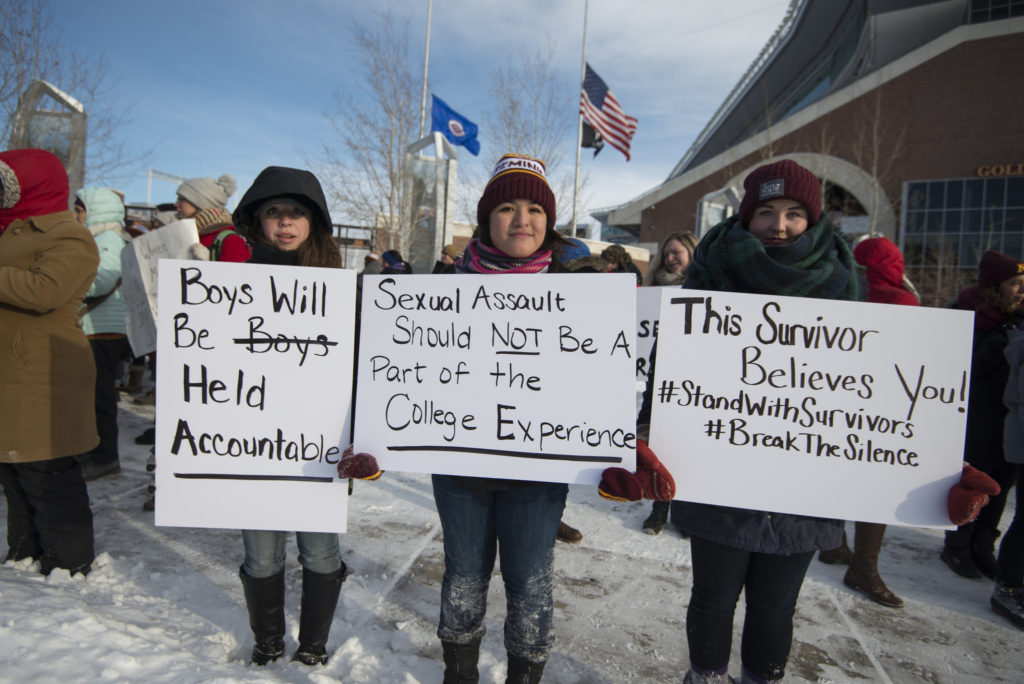

Sexual assault refers to any non-consensual or unwanted sexual act or contact, sexual coercion, and attempted or completed rape. Sexual assault is a significant issue on college campuses and can result in harms to survivors’ psychological and physical health, and their academic performance.

Universities are increasingly requiring their employees to report students’ experiences of sexual assault, regardless of whether the student wants to make a report. The authors describe these as “compelled disclosure policies.” Two federal laws inform school policies around mandated sexual assault reporting. First, the Clery Act requires that universities collect and publish the prevalence of sexual violence on and around campus. However, the Clery Act does not require any identifying information about sexual assault survivors or perpetrators to be reported.

The second guiding law is Title IX, which protects individuals against sex discrimination in education programs that receive federal funding. In 2011, the Dear Colleague Letter specifically identified sexual assault as a form of sex discrimination that was prohibited under Title IX. In 2014, a Q&A document about the Dear Colleague Letter defined “Responsible Employees,” who are required to report disclosures of sexual assault to the Title IX coordinator or another school designated official. Responsible employees are also required to report identifying information about the survivor, alleged perpetrator, and witnesses. Some states (e.g., California and Virginia) have gone even further, demanding that sexual assaults under certain circumstances also need to be reported to the police.

Although state laws requiring the reporting of sexual abuse toward children have been common for decades, college sexual assault reporting laws are different because most students are adults “with the right to self-determination,” state the researchers. According to the authors, “Proponents of compelled disclosure assert that it increases reports— enabling universities to investigate and remedy more cases of sexual assault—and benefits sexual assault survivors, university employees, and the institution.” However, the authors question whether these claims are supported by evidence.

“Education about the importance of consent is central in sexual assault prevention efforts; yet, compelled disclosure policies can and do result in reports made without survivors’ consent.”

Institutions are often navigating conflicting directives when developing Responsible Employee policies. Therefore, the authors ask, “How broad (or narrow) are compelled disclosure mandates, and what are their effects?” The researchers conducted a content analysis of a random sample of 150 public and private university sexual assault policies to answer this question. They focused on the scope of compelled disclosure policies, categorizing each policy by how many employees were mandated to report sexual assaults: all, most, few, or ambiguous.

Results show that 69% of the reviewed policies identified all employees as mandated reporters of sexual assault. Another 19% of universities identified most employees as mandated reporters. Only 4% listed few employees as mandated reports (e.g., responsible employees are limited to faculty/staff in leadership positions). Lastly, 8% of policies were ambiguous, meaning the researchers were unable to identify which staff were mandated reporters (e.g., a plan might say “most employees” are required to report, but to do not list who those employees are).

The researchers summarize, “these findings suggest that the great majority of U.S. colleges and universities—regardless of size or public versus private nature—have developed policies designating most if not all employees (including faculty, staff, and student employees) as mandatory reporters of sexual assault.”

Given that most universities require all or most employees to report sexual assault, it is critical to understand in what ways this may be helpful or harmful to survivors and institutions. Therefore, the researchers conducted a literature review to examine four assumptions underlying these policies:

Assumption #1: Compelled Disclosure Policies Surface More Sexual Violence. The authors present conflicting evidence that mandated reporting laws will increase the number of reports to the institution. Some studies support this claim, while others suggest survivors are less likely to disclose (e.g., to housing staff) if they know it will be reported to the university. Some research also indicates that people would be more likely to disclose an assault if they knew their decision about whether or not to report the assault was going to be respected.

Assumption #2: Compelled Disclosure Policies Benefit Survivors. The researchers again find conflicting evidence that does not explicitly support this assumption. Some studies have found that people imagine positive outcomes from compelled disclosure policies and that survivors of Intimate Partner Violence tend to support mandated reporting policies. However, these studies are limited in that they were often sampling people who have not experienced sexual violence, or people who have already chosen to seek out supports.

There are also significant possible harms to mandated reporting, such as reducing an individual’s agency. This is especially harmful to survivors of sexual violence because they often experience the assault as an “extreme loss of control” and regaining their sense of control is vital to healing. Survivors who experience a loss of agency from support providers have increased rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. Therefore, some survivors may not seek out services to prevent a loss of control under compelled disclosure policies. Lastly, survivors may experience “institutional betrayal” when they report the assault to their institution, and that institution does not provide them with the help and support they need (e.g., victim blaming, doing little to prevent assaults). Institutional betrayal has also been linked to PTSD.

Assumption #3: Compelled Disclosure Policies Benefit Employees. An argument for making all faculty mandated reporters is that it simplifies policies and can reduce staff and student confusion. However, research suggests a more complicated picture. Studies indicate that many mandated reporters are unprepared for the role and under-informed about their obligations. Also, individuals who are distrustful that disclosure policies will help students are less likely to abide by them. Policies that require faculty to report assaults may undermine trust in the teacher-student relationship and become a barrier to learning. Faculty are therefore often frustrated and angered by these policies.

Assumption #4: Compelled Disclosure Policies Benefit the Institution. The last assumption is that requiring all employees to be mandated reporters protects the institution from legal liability. However, again, there is no definitive evidence that this is the case. Broad compelled disclosure policies may inadvertently conflict with other Title IX directives, such as respecting survivors’ autonomy and privacy. Also, when an institution has so many mandated reporters, they may not be able to train them adequately. The authors note, “Responsible Employees who are inadequately or improperly trained could exacerbate survivor distress and trauma, for example by asking questions that communicate doubt or blame.”

Due to the lack of evidence supporting the above assumptions, and the many potential harms that compelled disclosure policies can have on survivors, the authors propose four survivor-centered alternatives. The authors state:

“There is an urgent need for alternative, innovative policies and practices. The overarching goal should still be rapid and appropriate institutional response to sexual violence, but there should also be a minimization of harm to students and respect for their right to self-determination.”

The researchers’ recommendations include employees being required to ascertain what a survivor’s wishes are and respect them, whether they want to move forward with a report or keep the disclosure private. Second, the authors recommend that universities create a restricted reporting option that provides an avenue for survivors to receive services without launching an official investigation. They suggest that this is modeled after the restricted reported option in the U.S. military, which resulted in increased disclosures.

Universities could also use a third party online reporting system, where students could make a record of the assault and choose to submit it at any time, or only submit if another student reports the same alleged perpetrator. Universities could also use a “blended” approach, where they offer more ways to access services confidentially or allow disclosures to be reported to a confidential source, rather than Title IX.

Sexual violence is a widespread issue, especially for women on college campuses, that can lead to significant mental health challenges for survivors. After the present article was accepted by The American Psychologist in June 2017, the Department of Education withdrew both the 2011 Dear Colleague Letter and the 2014 Q&A in September 2017, leading to more uncertainty about how sexual misconduct will be addressed on college campuses. Therefore, the author’s call for more research on effective and empowering strategies to address sexual violence on campus is even more critical. The authors conclude:

“With a combination of increased voluntary reporting and improved institutional response, universities could potentially remedy more cases of sexual assault, without sacrificing survivors’ autonomy.”

****

Holland, K. J., Cortina, L. M., & Freyd, J. J. (2018). Compelled Disclosure of College Sexual Assault. American Psychologist, 73(3), 256-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000186 (Link)

Do “Sexual assault is a significant issue on college campuses” ?

According to the cited study:

“Findings on the prevalence of sexual victimization on college campuses varied significantly among studies, making it difficult to synthesize results across the 34 studies.”

“Among studies measuring completed rape, defined as forcible vaginal, anal, or oral intercourse using physical force or threat of force (n 1⁄4 9), prevalence findings ranged from 0.5% (S12) to 8.4% (S21) of college women”

“Findings for studies measuring attempted rape, defined as attempted vaginal, anal, or oral intercourse using physical force or threat of force (n 1⁄4 3), were comparable and ranged from 1.1% to 3.8% (S6, S10, and S14) of college women.”

Uncertainty about the actual prevalence of sexual assault is very high.

Personally, I had never heard of sexual assault at the university before the “sexual panic” of recent years. I do not believe that sexual assaults are more or less important at university than elsewhere, nor that a great change has taken place in recent years.

Report comment