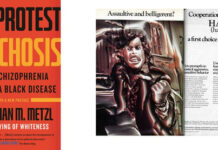

In this piece for Psychiatric News, King Davis, Ph.D. senior research fellow in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin, writes on how tracing the history of how the mental health of African Americans was characterized during slavery sheds light on why disparities in psychiatric care still exist.

In this piece for Psychiatric News, King Davis, Ph.D. senior research fellow in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin, writes on how tracing the history of how the mental health of African Americans was characterized during slavery sheds light on why disparities in psychiatric care still exist.

The proportionate number of slaves who become deranged is less than that of free coloured persons, and less than that of whites. From many of the causes affecting the other classes of our inhabitants, they are somewhat exempt: for example, they are removed from much of the mental excitement to which the free population of the Union is necessarily exposed in the daily routine of life. Again, they have not the anxious cares and anxieties relative to property, which tend to depress some of our free citizens. —John Galt, Report of the Eastern Asylum (1848), Williamsburg, Va.

In 2020, the Commonwealth of Virginia will acknowledge the 150th anniversary of the first mental institution for blacks in America and the theoretical and political roots that marked its segregationist origins. In this article, I will discuss changes in causal theories, legislation, and public opinion in Virginia that linked blackness, mental illness (lunacy), dependency, and dangerousness as the predictive aftermath of slavery. It was this combination of sentiments, fear, and experiences that contributed to long-term differences in mental health care (excess admission rates, severe diagnoses, treatment, delayed help seeking). In addition, this article describes current efforts to retain, restore, and increase access to the 800,000 historical documents that describe the historiography of this unique institution and the thousands of people who were admitted.