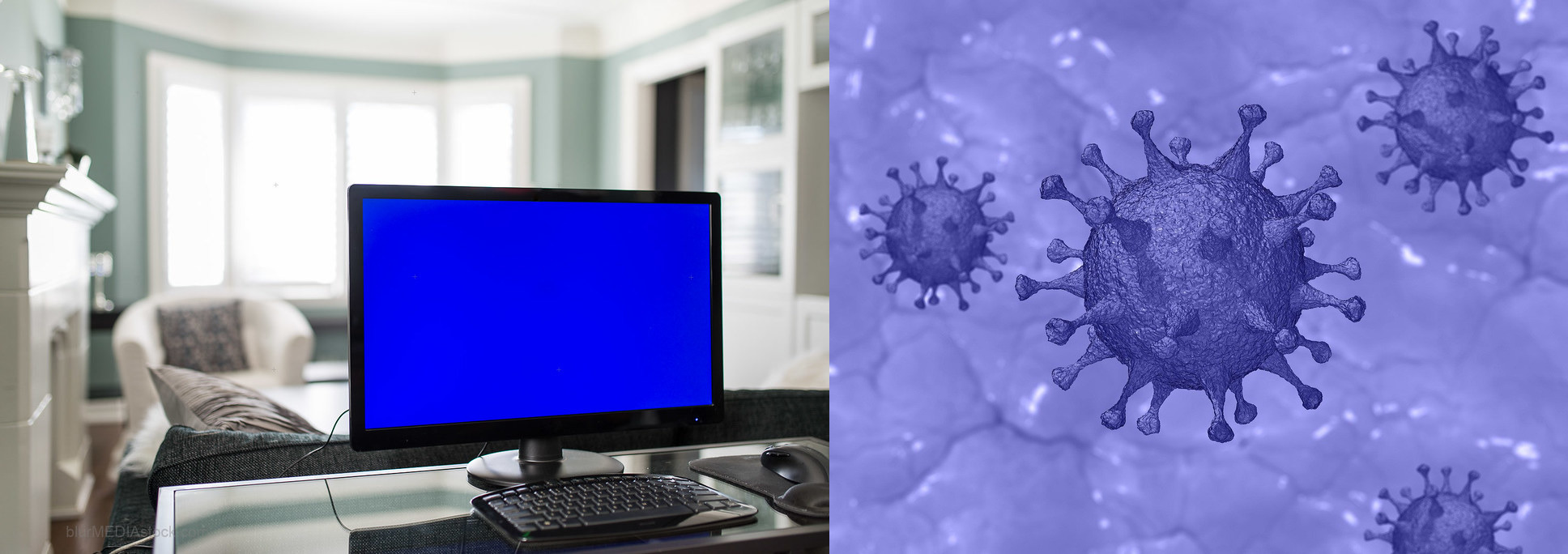

The rapid spread of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which has resulted in the deaths of thousands throughout China and now across the world, has contributed to the development of psychological symptoms, including anxiety, depression, and stress, in medical personnel as well as the general public. As COVID-19 is highly contagious between people, standard face-to-face approaches to mental health care have become risky for both patients and practitioners. The influx of COVID-19, and the subsequent increase of mental health issues associated with it, have called for creativity and the implementation of distance and telehealth strategies. At the same time, however, these screening and treatment interventions should be carefully evaluated and critiqued as they raise significant privacy and surveillance issues.

In China, a number of online mental health services have been developed and implemented to meet the needs of those affected by the outbreak.

Researchers, led by Bin Zhang of the Southern Medical University in Guangzhou, China, write, “. . . online mental health services being used for the COVID-19 epidemic are facilitating the development of Chinese public emergency interventions, and eventually could improve the quality and effectiveness of emergency interventions.”

The researchers examined 72 online mental health surveys associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. The surveys included populations such as medical staff, patients with COVID-19, students, the general population, and mixed populations, and also targeted areas both within and outside of Hubei province – where the epicenter of the outbreak, Wuhan, is located.

The researchers examined 72 online mental health surveys associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. The surveys included populations such as medical staff, patients with COVID-19, students, the general population, and mixed populations, and also targeted areas both within and outside of Hubei province – where the epicenter of the outbreak, Wuhan, is located.

A survey of 1563 medical workers found that depression was prevalent in 50.7% of personnel, anxiety in 44.7%, and insomnia in 36.1%. Additionally, 73.4% of medical staff reported being experiencing stress-related symptoms. While these survey results point to an overall increase in distress in these populations, it should be noted that they are based on flawed disease constructs whose validity and reliability have been repeatedly questioned.

Medical staff and the general public have been using online mental health education through online platforms like WeChat and TikTok during the outbreak in China. This has allowed for the timely dissemination of information to the public and medical staff alike regarding COVID-19 prevention, control, and mental health education. The Chinese Association for Mental Health published guidelines regarding how to cope with psychological symptoms associated with the pandemic.

Online counseling services have also been implemented by mental health professionals across institutions and universities in China following the rise of COVID-19. Additionally, online self-help resources, such as online cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression, anxiety, and insomnia, have been developed and implemented. Critics, however, have argued that these manualized telehealth therapies lack a robust evidence base, may leave out the key ingredients of successful therapy, including the therapeutic relationship, and raise issues of privacy and data concerns.

Further, artificial intelligence (AI) programs have been developed to address the needs of individuals in crises. The authors give the example of the Tree Holes Rescue program, which assesses suicide risk by analyzing messages posted on Weibo. While these AI screening programs are being promoted, particularly during the pandemic, these programs raise a number of issues about the potential for overdiagnosis, mass surveillance, and entrenched biases and discrimination.

Overall, the online mental health services being implemented by China during the COVID-19 pandemic point to the increased mental health needs of specific and general populations. It has also allowed for mental health education and information regarding the virus to be dispersed across a broad audience, including the general population and medical personnel.

Moreover, adapting mental healthcare to include online delivery of services is critical during the pandemic, wherein social distancing is recommended to slow the spread of the outbreak. According to the researchers, the ability to provide therapeutic services, self-help interventions, and risk assessment online is crucial during a time when face-to-face contact is potentially harmful to either the mental health professional or the client. However, these online screening tools and treatments remain unproven and carry significant risks.

****

Liu, S., Yang, L., Zhang, C., Xiang, Y-T, Liu, Z., Hu, S., & Zhang, B. (2020). Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (Link)

Covid-19 causes anxiety.

As does a lot of news. News is mostly negative on any given day.

The anxiety from negative input is not a mental illness. It is a normal response to stressful situations.

Some of us are more prone to experiencing anxiety, stress.

They are nice to be able to be talked about, talking about these feelings normalizes them.

Report comment

Hi, Ashley– thanks so much for this! Do you have any idea what interventions they have found most useful? I just moved most of my practice online, I do have some Chinese and South Korean clients. I’d love to know what is working and what isn’t for patients and providers on the front lines. I don’t want to just offer deep breathing exercises (THAT would be absurd, for people who are having trouble breathing) and cookie-cutter CBT crap.

Generally, I like existential interventions like life review for people facing life-threatening challenges, and I have my own weird toolkit of pain-control interventions that might be useful for people who have got tubes down their throats, but it’s all stuff I developed as needed, often during my own hospital stays.

I want to go to war. So do my colleagues. I’ve got the hardware and it works most of the time, but any resources you have, anything they’ve learned in China would be very useful.

Thank you, also, for noting the perils of robo-therapy and privacy issues.

BTW, Sam, I totally agree this is not mental illness, and Boans, yeah, the idea of blaming China just makes me want to hurl.

Report comment

In my country your information is ‘confidential’ until it’s not. If the State wants information from a doctor or your lawyer they can threaten and intimidate them using ‘coercive methods’. If they should believe that the State means it when they tell you they will “fuking destroy” you and your family, then that’s seen as their problem. They didn’t really mean it but because you breached your promise well……. I know for a fact that police used a psychologist to obtain information regarding “who else had the documents” in my instance.

So this rubbish about pointing the finger at China for what we are doing in our own back yards seems a little rich. They’re just a little better at it is all.

Report comment