Editor’s note: This is a review of existing formal and informal guidance on psychiatric drug withdrawal protocols. This piece should not be interpreted as medical advice or as an instruction to approach withdrawal in a particular way.

Important: Tapering guides advise that unless there is a risk of immediate serious illness from continuing, psychiatric drugs should never be stopped abruptly.

General Issues

Lack of formal research

Although the first generation of “psychotropic drugs” arrived in the 1950s and thus have been regularly prescribed for more than 60 years, there has been little research on how to best taper from these medications. In the absence of such research, there is no good “evidence-base” for tapering protocols.

Withdrawal experiences vary greatly

Many factors influence how quickly someone could or should come off psychiatric drugs. Based on the anecdotal experiences of people in support groups or reported in the media, the majority of people seem to recover in time, some fully, some to a lesser extent. The unknown is the time taken to recover which varies immensely and is dependent on many individual factors.

Factors influencing withdrawal difficulty include:

- Length of time taking the drugs (those who have been on longer may need to take longer to withdraw).

- The dosage taken (higher dosages can mean longer needed to withdraw safely).

- The half-life of the drug in question (drugs that are quickly eliminated from the body tend to make withdrawal felt more quickly or more severely).

- The age of the person (often, but not always, younger people find withdrawal easier than older people). This may be particularly true for children.

- The general health of the person coming off (since withdrawal can be physically taxing, those who are fitter seem to fare better).

- The use of other prescribed or street drugs (polypharmacy can complicate withdrawal, as can use of street drugs).

- Prior failed withdrawal attempts (trying and failing to come off previously can make the psychological hurdle more challenging).

In short, the best tapering schedule is one that allows the person to withdraw while avoiding or minimizing withdrawal symptoms to a level where they can be tolerated and do not require major life adjustments. Since people have different tolerances, withdrawal is likely to need a person-centered, almost unique approach.

Tapering speeds

There is a wide disparity between tapering guidelines developed by professional organizations and the advice and practices that have originated within the “lived experience” community. The professional guidelines typically recommend much shorter tapers than recommended by those with lived experience, and protocols for lowering doses may vary greatly as well.

Antidepressants

Numbers affected by withdrawal

There have been only a small number of research projects looking at the number of people reporting withdrawal when coming off antidepressants. In a recent UK survey undertaken by Professor John Read and Doctor James Davies, 56% of people experienced withdrawal effects, with 46% of those describing the effects as severe. A wide range of experiences is reported between those who can come off relatively easily with mild, short-lived symptoms, to those who experience protracted withdrawal lasting many months or sometimes years.

Professional guidelines

Professionally produced guidelines commonly recommend short tapers of between two and four weeks, usually achieved by halving dosages or skipping dosages entirely. Feedback from lived experience communities shows that this advice can often lead to withdrawal symptoms. The advice given by some prescribers to skip doses appears to have no evidential support and is not mentioned in “discontinuation advice” produced by pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Clinical Problem. Mireille Rizkalla, PhD; Bryan Kowalkowski, OMS III; Walter C. Prozialeck, PhD

In a 2001 paper entitled Steps Following Attainment of Remission: Discontinuation of Antidepressant Therapy, Richard C Shelton MD observed:

“Unfortunately, no drug-specific protocols for discontinuing antidepressants have been established. Prescribing information for each drug typically lacks recommendations for the rate and duration of tapering or criteria for antidepressant discontinuation. A review of the literature on these phenomena, however, shows that a slow taper is uniformly recommended. Inasmuch as antidepressant treatment generally continues for months to years, so should the taper be accorded adequate time to take effect. Several months may be required, depending on the dose, the pharmacologic profile of the drug, the duration of treatment, and the response of the patient.”

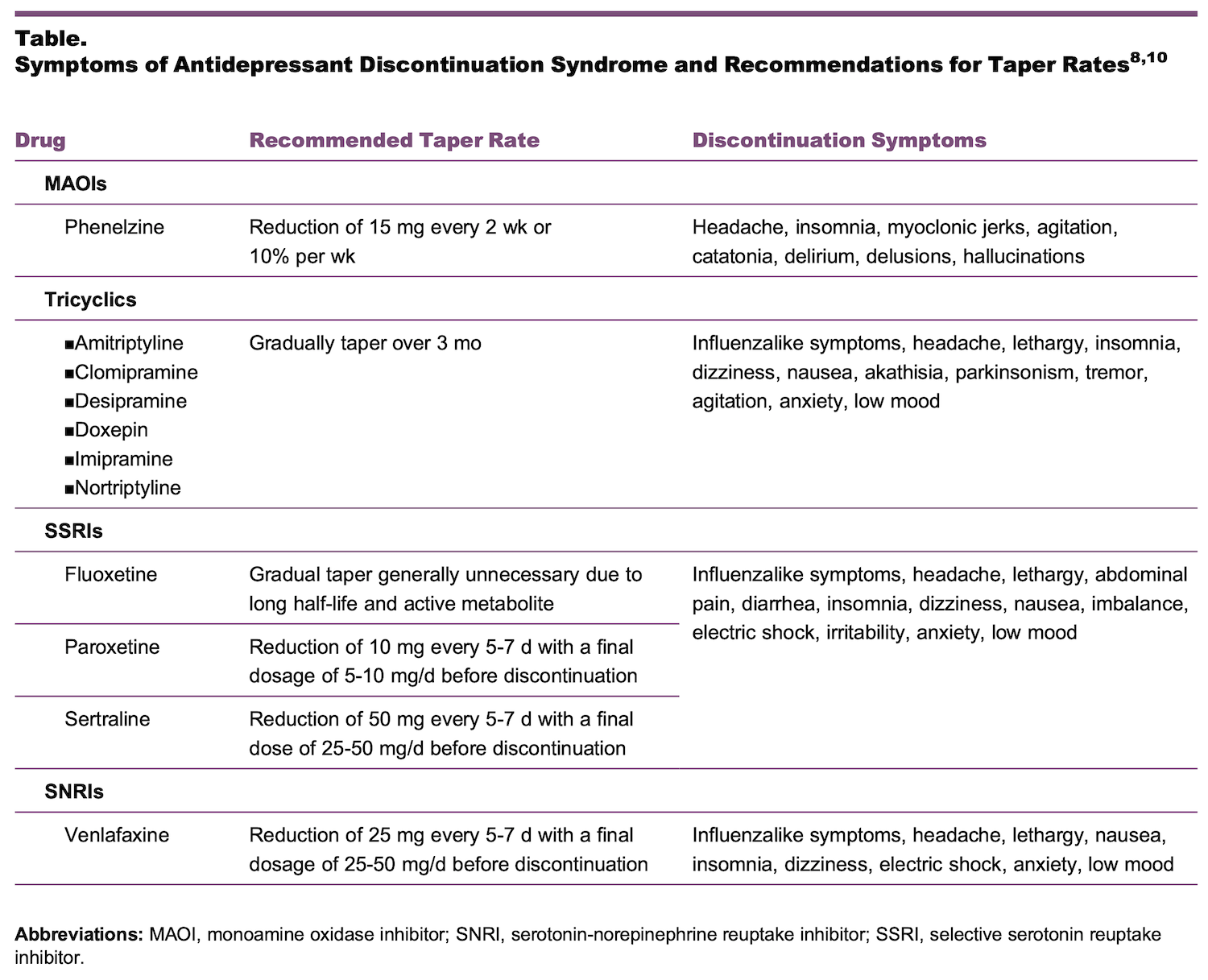

He gives the following recommended taper rates:

*It should be noted that the advice that tapering is not needed for Fluoxetine due to its long half-life is commonly given but has been challenged in a Lancet paper by David Taylor and Mark Horowitz.

In 2009, Tint, Haddad and Anderson compared a three-day (short) with a 14-day (longer) antidepressant taper prior to switching to a new antidepressant. They noted that there was very little difference between the tapers with symptoms occurring in 46% of patients with a similar frequency in those with short (7/15) versus longer (6/13) taper. They reported that four patients, all on paroxetine, developed emergent suicidal ideation after taper. They concluded that there is little advantage to a two-week taper over a three-day taper when switching antidepressants.

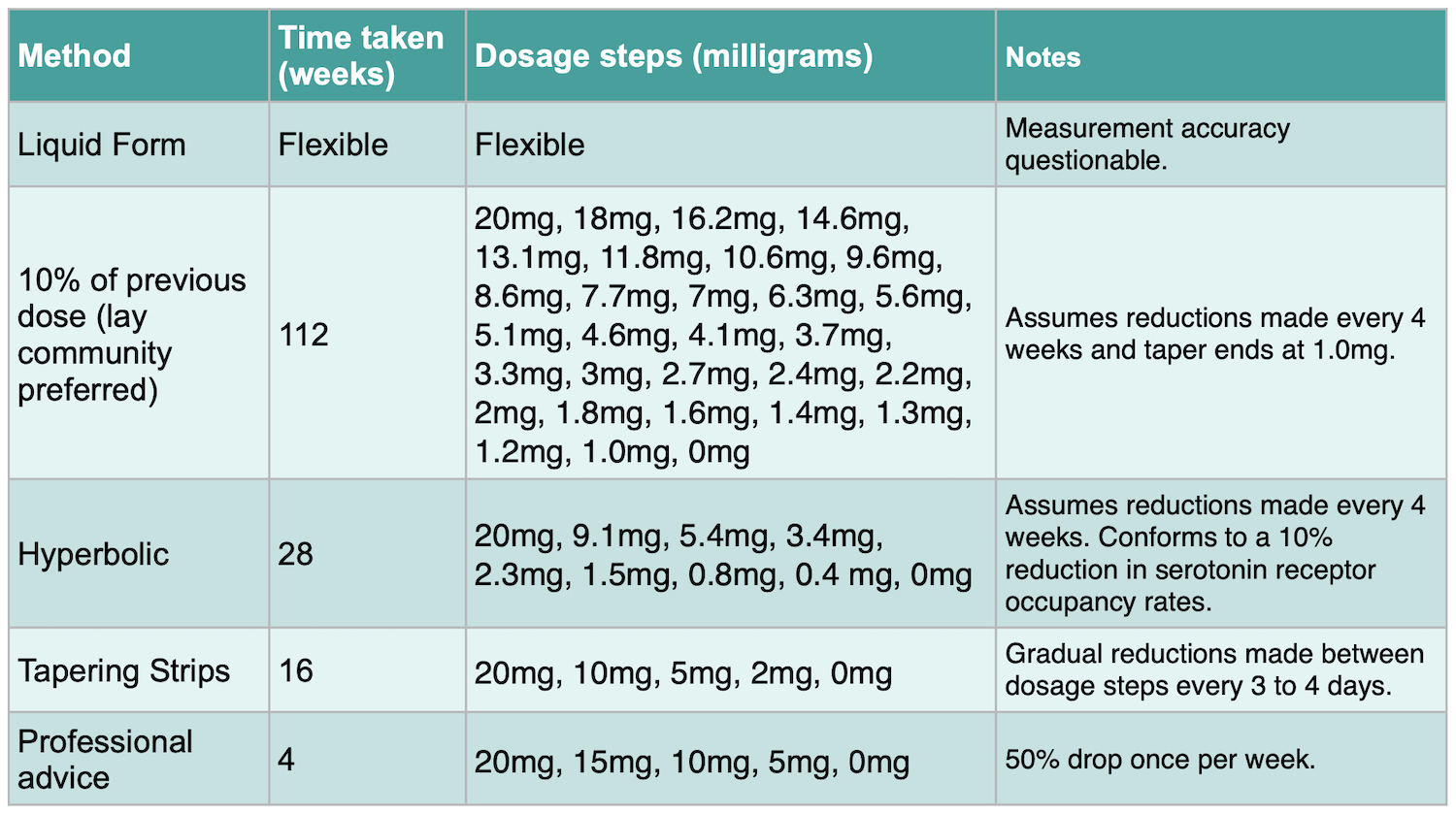

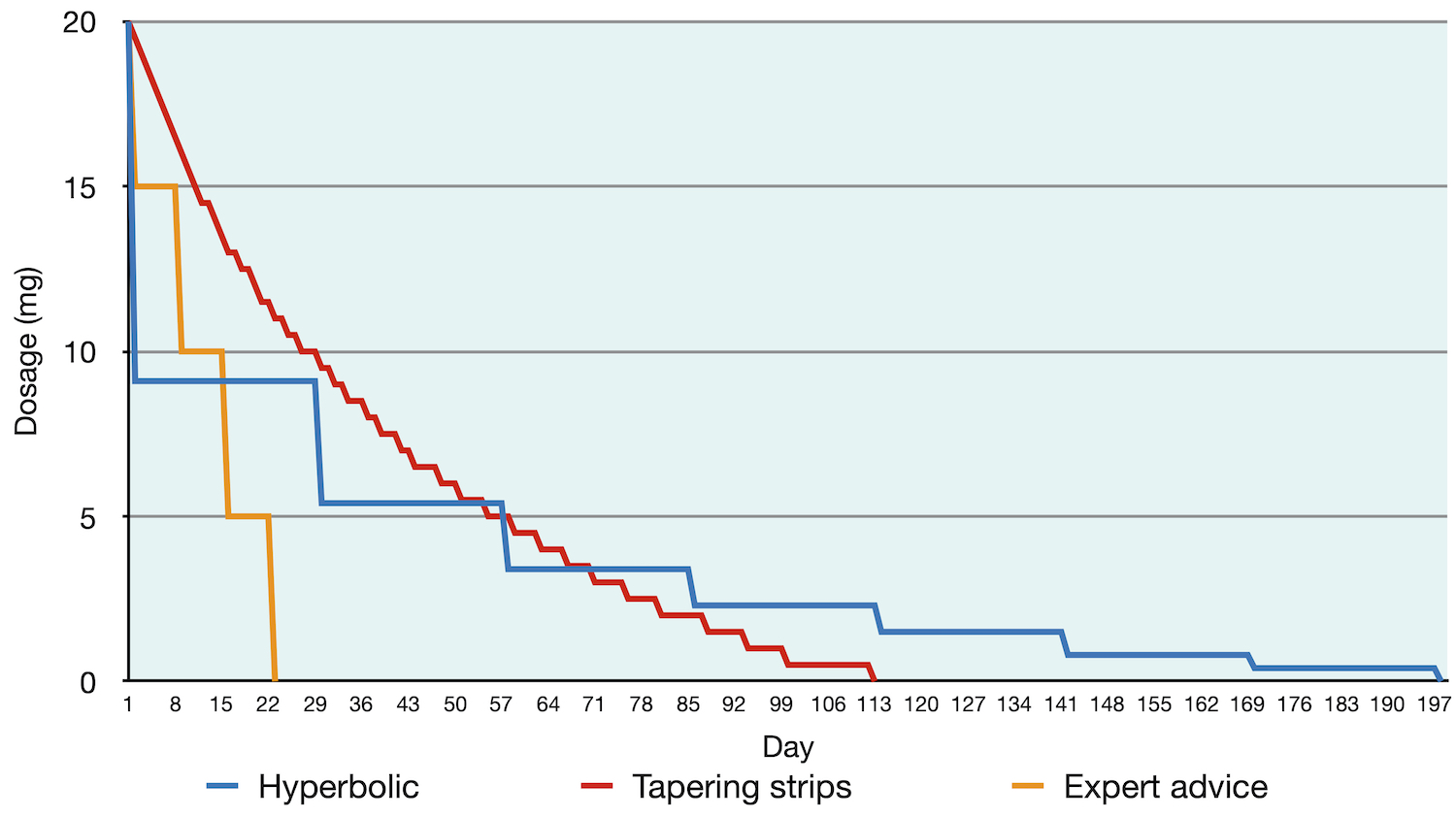

In his 2019 Lancet paper, Mark Horowitz, a psychiatric researcher with personal experience, analysed serotonin receptor occupancy rates to determine what he called a ‘hyperbolic’ dosage reduction. Antidepressant drugs retain much of their potency even at very low dosages. The result of this is that people may be able to reduce more quickly in the initial part of their withdrawal but may need to slow down and reduce very gradually towards the end. In his paper, this is called ‘stop slow as you go low’. In his paper, he noted that studies show that there is very little or no difference in symptom severity between reducing over 14 days when compared to stopping abruptly.

In his work on venlafaxine tapering strips, Peter Groot reviewed the experiences of 895 people who wanted to withdraw from Paroxetine (an SSRI) or Venlafaxine (an SNRI). Ninety-seven percent had tried to withdraw previously, many making multiple attempts and failing. In his study of outcomes with tapering strips, 71% were successful and tapered off over an average of 56 days (with a range between 28 days and 84 days). The participants in the study had used an antidepressant for between two and five years.

User-Informed guides

In many lay communities, it is common to find the suggestion of tapering at no more than 10% per month (sometimes suggested as a five percent reduction per two weeks). This reduction is made on the previous dosage. For example, a person taking 20mg would first reduce by 2mg to 18mg. The next reduction would then be 10% of 18mg, which is 1.8mg giving a dosage of 16.2mg. The next reduction would then be 10% of 16.2mg and so on.

There is also length of exposure to consider. An individual may reduce over many years, but this adds additional exposure to the drug during this tapering process. Reducing more quickly would limit this exposure. There is a balance to be found between reducing slowly enough to minimize withdrawal symptoms, but quickly enough to limit drug exposure.

Tapering duration

Most recent papers agree that dosage reductions should not be daily, but rather should proceed in steplike fashion, with a pause between one reduction and the next. Most guidelines informed by lived experience advise to not exceed a 10% decrease per four weeks. Reducing in this manner can be difficult because it may involve cutting pills and this may not produce accurate dosages. In addition, it can make for extremely long tapers. This slow tapering routine may be necessary for some people, but not all.

On the other hand, reductions made by using Dutch tapering strips are commonly made every three to four days. The tapering strips also provide accurate dose measurements.

There is currently no accepted standard, or evidence-based time period, for withdrawing from a psychiatric drug. Given the many factors involved, any such standard is likely to lead some people into difficulty.

Withdrawal also waxes and wanes. It is not a fixed or linear experience. Some report having little difficulty coming off the drugs yet may find they experience symptoms many weeks or months later. Others report that withdrawal symptoms were a constant problem during dosage reduction, but eased considerably once off the drugs. Equally, some people report symptoms both during and after withdrawal, with a group of people never feeling that they have completely recovered.

Special considerations

Akathisia is important to watch for both during withdrawal and for some time afterwards. Akathisia is described as an intense urge to move which can be felt internally where someone observing doesn’t see movement, or externally in which case an observer will see movement or agitation. Akathisia is more commonly associated with coming off antipsychotic drugs, although has been associated with coming off antidepressant drugs too. There is some evidence that rapid withdrawal is more likely to trigger akathisia, but for some people, it can be felt even after a carefully managed gradual reduction.

Post-acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS) is the name given to unremitting symptoms that persist long after the drug has been stopped. Due to the lack of research and inability to agree on an appropriate definition, PAWS is not listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders. It is also unrecognised by most medical associations. The concept of PAWS has, however, been adopted by drug and alcohol rehabilitation services.

Such protracted symptoms, which may persist for months or even longer, are thought to be due to the fact that the drug exposure alters brain physiology (increasing or reducing the density of neurotransmitter receptors, for example), and it may take an extended period for such brain physiology to renormalize.

Six-week ‘detox’ programs: These programs may (or may not) have merit for stopping street drugs, but they are likely to be inappropriate for psychiatric drug withdrawal, given that any withdrawal regimens need to be personalized, with tapering speeds adjusted in response to individual withdrawal experiences.

In Summary

The following summary of withdrawal protocols for antidepressants is by James Moore, who is director of MIA Radio. He is also the creator of the “Let’s Talk Withdrawal” podcast.

There is no ‘one size fits all’ for psychiatric drug withdrawal, either for dosage reduction or length of time to take between dosage reductions. Some people can reduce more quickly than others and suffer very little by way of withdrawal. Others can reduce very gradually and slowly and still experience symptoms long after stopping. A small number of people may not feel that they ever fully recover to their pre-exposure condition. Many people will only know how they will find withdrawal when they come to make their initial reduction and then reflect on that experience.

A person considering withdrawal might wish to balance the drug exposure time with the speed of withdrawal, choosing the taper that minimises withdrawal but also gets them off in the minimum time. A person should, if possible, consider choosing the most accurate and easiest method of dosage reduction available. There is no reason to make dosage cuts equally each time, it may be preferable to reduce by bigger steps initially, then more slowly towards the end (a hyperbolic reduction). This limits exposure time but also takes account of the need to go slowly in the latter stages.

In short, the correct tapering schedule is one that allows the person to withdraw while avoiding or minimising withdrawal symptoms to a level where they can be tolerated and do not require major life adjustments. Since people have different tolerances, withdrawal is likely to need a person-centred, almost unique approach. The goal of dosage reduction is to force the body to readapt to the lack of the drug or to undo the compensations made to the presence of the drug. If this forcing is too fast, withdrawal may be unbearable, but the process of triggering the re-adaptation is a necessary part of the healing process.

Key papers and references

Davies J, Read J. A systematic review into the incidence, severity and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: are guidelines evidence-based? Addict Behav. 2019;97:111-121. doi:10.1016/j. addbeh.2018.08.027

Groot PC, van Os J. Antidepressant tapering strips to help people come off medication more safely. Psychosis 2018; 10: 142–45.

Hengartner MP, Davies J, Read J. How long does antidepressant withdrawal typically last? Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):487.

Horowitz MA, Taylor D, Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019; 6: 538-546. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(19)30032-X/fulltext

Alicja Lerner, Michael Klein, Dependence, withdrawal and rebound of CNS drugs: an update and regulatory considerations for new drugs development, Brain Communications, Volume 1, Issue 1, 2019, fcz025, https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcz025

Rizkalla M, Kowalkowski B, Prozialeck WC. Antidepressant Discontinuation Syndrome: A Common but Underappreciated Clinical Problem. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2020;120(3):174–178. doi: https://doi.org/10.7556/jaoa.2020.030

Shelton RC. Steps Following Attainment of Remission: Discontinuation of Antidepressant Therapy. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(4):168–174. doi:10.4088/pcc.v03n0404

Tint, A., Haddad, P. M., & Anderson, I. M. (2008). The effect of rate of antidepressant tapering on the incidence of discontinuation symptoms: a randomised study. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22(3), 330–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881107081550

The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines 2001; 6th Ed, p64 – 65

Surviving Antidepressants, https://www.survivingantidepressants.org

The Inner Compass and Withdrawal Project https://withdrawal.theinnercompass.org

The Ashton Manual, https://www.benzo.org.uk/manual/

Research compiled by James Moore

Copyright Madinamerica.com

And forever more, psychiatry knows, but lies so much that nothing that they say is reasonable.

The reason so many no longer hold psychiatry as a reasonable profession is because of the lies they used.

The actual medical field is soon to follow.

They were duped by pharma, although it was not really duping, they simply needed something other than to say the truth, and the truth was “we don’t know”.

So then they all jumped into bed together and is one reason people are looking at their own means to not ever be dependant on systems that cannot be trusted.

There are movements everywhere to take back authority.

No one but me owns my mind and body.

Report comment