A new study, published in Psychosis, describes the critical elements in Hearing Voices Groups (HVG) that lead to helpful changes and significant transformations in the lives of participants. The study, conducted by Gail Hornstein at Mount Holyoke College, found that people’s experiences of voice-hearing are incredibly variable and that some of the key features of HVGs enable positive change. These features include the non-judgmental attitude and non-hierarchical structure of the groups, as well as efforts within the groups to build a sense of safety and allow participants to express themselves freely.

“This atmosphere allows for greater curiosity about their own and others’ experiences, less fear about acknowledging or exploring them, and a sense of belonging, connection, and hope,” Hornstein and her co-authors, Emily Robinson Putnam and Alison Branitsky explain.

Experiencing auditory hallucinations, such as hearing voices, can be distressing. For decades now, hearing voices has been considered by most mental health disciplines as a pathological experience and treatments developed with the goal of eliminating them. Current mainstream approaches focus on the use of medications to reduce the intensity of voices or eliminate them altogether.

However, many voice hearers find that these medications are not helpful and bring with them a series of side effects that pose serious health risks and are often disabling. For that reason, there are growing efforts, especially coming from the consumer/survivor/ex-patient community, to find ways to address the distresses that may be associated with voice hearing without pathologizing the experience or relying on interventions that are seen as traumatic and not helpful.

“Many voice-hearers, however, find medication ineffective in reducing their distress or intolerable due to its adverse effects,” the authors write.

HVGs are peer support groups established by advocates to create spaces where voice hearers can share experiences with others who are coping with similar challenges. Past research has found that HVGs have distinct features and offer several benefits to participants, such as forming new social connections, finding ways to cope with voices, and experience less distress associated with voices.

HVGs exist in more than 30 countries, and members report positive life changes as a result of participating. Nevertheless, HVGs have not yet been systematically researched and are often met with skepticism by mental health professionals for not being evidence-based.

The nature of HVGs poses challenges to the research community. Because they are not a structured intervention that takes place in a limited time frame, traditionally accepted research methods are not the most appropriate to understand the effectiveness of these groups. Additionally, the dominant biomedical model focuses more on symptom reduction/elimination as the primary outcome of treatment, which is not the case for HVGs.

To address this issue, the researchers employed a qualitative approach to explore how the groups function in a way that is seen by participants as effective and to describe the key features that make HVGs unique and different from other support groups. They write:

“Since HVGs were explicitly developed as an alternative to interventions focused on voice cessation, their success cannot be measured by the extent of ‘symptom reduction’ or ‘absence of hallucination.'”

Researchers recruited participants from across the US who attended HVGs and obtained data from 113 respondents. Participants were administered a questionnaire with open-ended questions that explored voice-hearing history, people’s experiences in HVGs, changes in life that happened as a result of participating in the groups, and comparisons with other forms of supports/interventions.

They invited a subset of 15 participants to a follow-up interview where a set of questions about voice-hearing experiences were asked along with an invitation to freely explore and talk about other relevant aspects of participating in HVGs.

79% of participants reported helpful changes in their voices as a result of participating in HVGs. Participants also reported a reduction in the use of hospitals and crisis services, a shift in the need for medication including tapering and stopping completely, improved sleep, and an ability to restore or pursue important life projects such as finding a job, going back to study, and improvement in social connection.

The researchers found that the most important feature of voice-hearing is how variable it is. Participants reported a wide range of experiences with voices, some hearing them all the time, others occasionally; some found the voices helpful while others were distressing; some voices are identifiable by hearers, and others aren’t. This finding is relevant because it points to the importance of offering supports that are responsive to the variability of experiences. The authors add:

“People with widely varying experiences come to HVGs, and it is the complex constellation of elements in these groups, and the processes by which these elements interact, that make HVGs uniquely responsive to disparate needs and effective in meeting them.”

The study authors describe two classes of elements that characterize HVGs: the style of interaction and content. HVGs offer a non-judgmental space for people and employ a non-hierarchical structure where facilitators invite folks to share freely and explore experiences. Creating a safe space allows for a sense of belonging and connection to be developed among participants. Groups are not focused on specific behavioral outcomes, and participants have the opportunity to both help and be helped in the context of the meetings.

As for the content, avoiding jargon and prescriptive language while fostering meaning-making allows participants to make sense of their experiences in the context of their lives. The combination of these elements enables significant changes in participants’ lives.

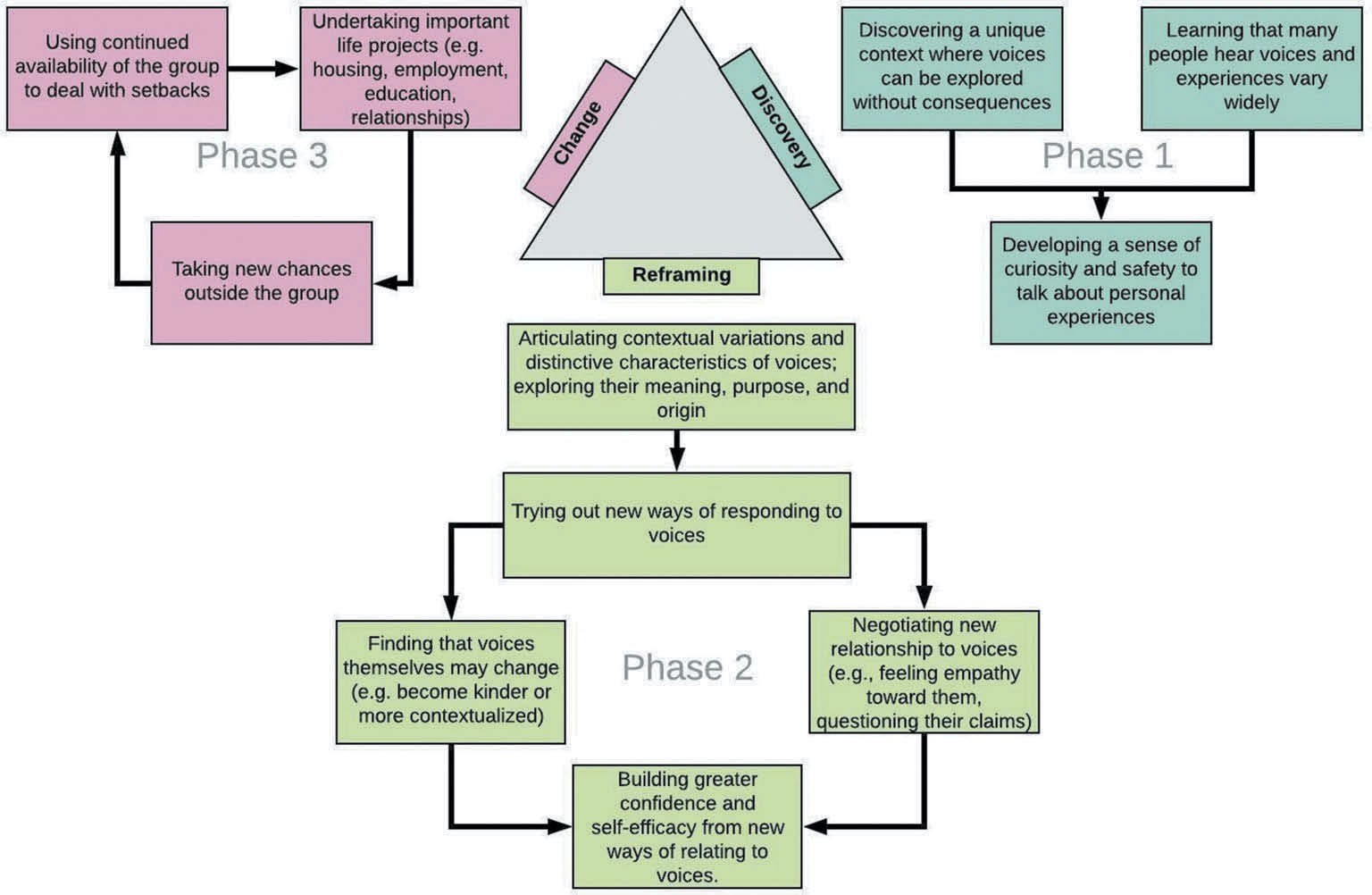

Researchers developed a model to describe the processes that take place in the HVGs, leading to transformation. Researchers used the data to identify commonalities across experiences and developed the following model:

This model is dynamic, as participants often move through phases according to their specific needs. There is great flexibility in the groups, which allows people to join regardless of where they are in their journey. A wide variety of topics can be explored in any given HVG. Participants report talking about medications, spirituality, trauma, ways to cope, and conversations go from the abstract explanations of phenomena to concrete strategies for change.

“This broad range of topics means that members are continually exposed to ways of thinking different from their own while being under no pressure to adopt any of them,” Hornstein and co-authors write.

HVGs are a unique type of support that is largely seen as helpful by those who participate in them. Valuing the person as the expert of their own experience and creating a supportive environment where participants can explore and generate meaning collectively are key features of the groups.

HVGs can be well integrated with other supports and don’t compete with other services traditionally offered by mental health systems. It is, however, distinctive in how it moves away from bio-medical explanations of voice-hearing and offers a concrete intervention that promotes positive changes in participants’ relationships with the voices which, in turn, translates into an improvement in several dimensions of life, including relationships with others, service utilization, and engagement in fulfilling life projects.

This study helps us better understand how important it is to offer supports that account for the wide range of experiences that go beyond the presence or absence of voices. Indeed, hearing voices can have different meanings and varying impacts on people’s lives.

The results further strengthen the need for knowledge equity in the mental health field by showing that traditional and professional understandings of voice-hearing focus on certain aspects of experiences, often negative. This partial understanding results in interventions that may not be helpful and can sometimes be harmful.

HVGs are growing in the US and internationally, perhaps because of how helpful they are perceived to be by their participants and how they can promote positive changes in people’s lives while staying away from harmful, violent, stigmatizing, and coercive practices.

****

Gail A. Hornstein, Emily Robinson Putnam & Alison Branitsky (2020): How do hearing voices peer-support groups work? A three-phase model of transformation, Psychosis, DOI: 10.1080/17522439.2020.1749876 (Link)

I am a participant these groups. I am person in recovery journey involved hospitalization yada yada straight jacket yada yada. These groups allow freedom discuss these experiences. I sing GEORGE MICHAEL on my fb page Freedom to give respect the groups.

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=148657740068432&id=100047726207323

Report comment

I want to participate this groups .What to do.

Report comment