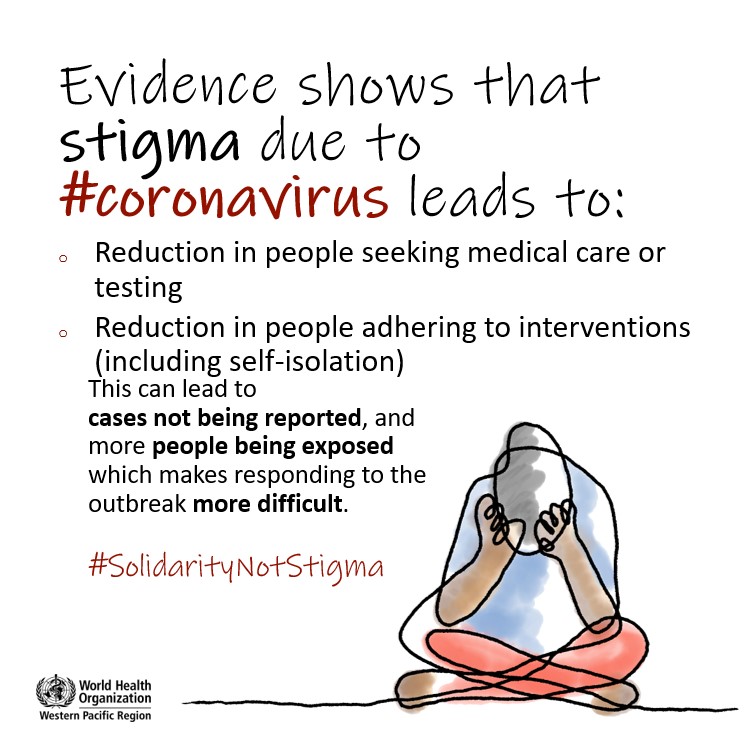

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold, prominent global health researchers Carmen H. Logie and Dr. Janet M. Turan, are calling on governments to begin implementing strategies to reduce COVID-19 stigma. Their article, published in the journal AIDS and Behavior, highlights the tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and social stigma.

As the Research Chair in Global Health Equity and Social Justice with Marginalized Populations in Canada, Logie’s work focuses on examining the links between forms of stigma and health equity, pointed out the danger of stigma. The researchers draw on historical and current approaches to illness, including experiences with HIV, to inform COVID-19 stigma reduction public health efforts.

“There is a long history of othering in conceptualizing illness, whereby the sick are separated from the healthy. Illness has been constructed as both evil predators and personal responsibilities, contributing to social rejection,” Logie and Turan write.

In the article, the authors discuss how four different public responses, including physical distancing, travel restriction, misinformation, and engaging affected communities, can increase the social stigma associated with the COVID-19 and potentially have a negative impact on public health. They also provided insight into stigma mitigation efforts, drawing on experiences with HIV research.

In the article, the authors discuss how four different public responses, including physical distancing, travel restriction, misinformation, and engaging affected communities, can increase the social stigma associated with the COVID-19 and potentially have a negative impact on public health. They also provided insight into stigma mitigation efforts, drawing on experiences with HIV research.

First, they encourage people to be aware of how physical distancing, while it is a necessary practice under the current public health policy, can exacerbate othering, avoidance, and mistreatment of people associated with COVID-19.

“While there are no direct parallels to HIV with physical distancing, HIV has long contended with the tension between negotiating intimacy and physical connection in a pandemic,” the authors add.

They propose that the practice of physical distancing should be accompanied by stigma-reduction messaging to foster empathy, making these restrictions more sustainable over time. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) has also suggested policies that motivate people to practice non-stigmatizing physical distancing.

Travel restrictions such as lockdown and quarantine are helpful for COVID-19 containment but can also be used as a means of social control. Studies show that travel restrictions can increase stigma and have negative impacts on people’s mental health.

“COVID-19 travel restriction may also facilitate stigma and xenophobia by reproducing the social construction of illness as a foreign invasion, in turn reinforcing social hierarchies and power inequities,” the authors explained. Similarly, there are 48 countries still have travel restrictions for people with HIV, and such policies are not evidence-based and compromise the human rights of people with HIV.

Once again, the authors highlight the need for an alternative approach to COVID-19 travel restrictions that include anti-stigma and anti-xenophobia public messaging. They believe that legal authorities should empower people in communities to protect their own and others’ health instead of criminalizing people who have breached COVID-19 public health policies.

Third, the authors call for long-term investment in reducing social inequities amid the COVID-19. Social inequities exacerbate COVID-19’s impact on marginalized communities. People living with psychosocial disabilities, people experiencing homelessness, refugees, undocumented immigrants, and LGBTQ+ people are all at higher risk for COVID-19 and the stigma associated with the COVID-19.

“An extensive body of HIV-related stigma research has shown that multiple stigma dimensions can negatively impact health practice and outcomes,” the authors noted. “Public health responses regarding COIVD-19 should deploy stigma-reduction strategies not only from intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions but also from structural dimensions such as legal issues, policies, and human rights. Not only the interventions should provide up-to-date knowledge and correct misinformation, but interventions should also address health policies and institutional practices.”

Lastly, the authors argue that we should engage the people most affected by COVID-19. However, those who are most likely to be affected are also more likely to experience barriers to research participation due to social and health disparities. With this particular challenge, the author suggested researchers apply creative, web-based, and community-engaged strategies to reduce participation barriers.

“Lived experiences of COVID-19 and other intersecting stigmas can inform contextually specific and stigma-informed public health approaches,” the authors write.

In conclusion, Logie and Turn argue that an “intersectional lens can improve understanding of the ways that COVID-19 stigma intersects with gender, race, immigration status, housing security, and health status, among other identities.”

“We need more than information to reduce COVID-19 stigma — multi-level strategies can address underlying stigma drivers (knowledge, misinformation) and facilitators (health policies, institutional practices).”

****

Logie, C. H., & Turan, J. M. (2020). How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS and Behavior, 24, 2003-2006. (Link)

What scares me far worse than the thought of death itself–or even the deaths of my beloved Boomer parents–is losing touch with our humanity. If I see someone in need who can’t be helped otherwise I’ll gladly expose myself and stay in quarantine later.

Report comment

“Stigma” is an interesting word. It has a meaning within the “mental health community” that I’m not sure I even understand. Originally, it simply meant something obvious about you that gave you a certain identity. Like needle marks on your arm would brand you as a former drug addict. Now we see it used in connection with having a criminal record, or bad grades in school. Or getting a “mental illness” diagnosis.

But it is often used in the context of having the effect of someone not seeking “care” when they should. The mental health system wants to remove “stigma” to get more customers! That’s what really matters to them.

The language used by these authors is so dense and (to me) insincere, that it is unclear to me what they are really talking about. My guess is that they just want more patients.

Report comment