“Madness”

After Prohibition, America’s view of alcohol addiction (now “alcoholism”) had shifted from a belief in endogenous addictiveness for everyone who drank, to endogenous addictiveness for only those predisposed to becoming alcoholics. This allowed the Temperance movement to accept the existence of alcohol moderation. Ingestion of the drug, alone, was no longer enough to diagnose a drinking problem. It had to be accompanied by specific symptoms, such as higher than “normal” use, withdrawal symptoms, and socio-economic problems (i.e., criminal trespasses and bankruptcy).

A partial catalyst for this change was the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous. This group brought to mainstream culture the idea of a physiological set that predisposes people to becoming addicted to alcohol. This new mindset allowed the temperance strategy to move from criminalization of booze, to focusing on treatment and advocacy for the “chosen few” alcoholics.

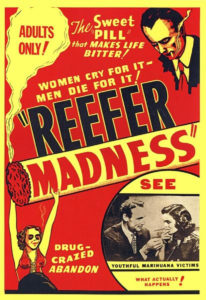

One year after the creation of Alcoholics Anonymous, and thereby the innovation of prepositional causes of addition, Reefer Madness was released. With its melodramatic and dread-inducing portrayal of the use of marijuana, it coded a new drug with many of the old temperance movement beliefs. Using the drug even once leads to a path of ruin that will affect anyone and everyone who uses it. Once you go down the path, you will fall victim to death and despair, with death sometimes being the more favorable outcome.

Today, the film is viewed as nonsensical propaganda and embraced by film-cult audiences as a piece of nostalgia. Yet, within the melodrama lies an important truth of those times.

Even though the alcoholism movement was rising, predisposition and the possibility of moderation was not extended to a “hard drug” use, such as a marijuana or heroin. In the case of these “hard drugs”, use alone was still seen as enough to diagnose the person as an addict. America kept the prohibition ideals for a certain set of drugs which, as we discussed in part II, were associated with oppressed races and ethnicities.

Through the 1950s, prohibition forces transitioned their focus from liquor law enforcement towards increased enforcement of the drug laws we’ve discussed before. Just as was said about alcohol, the stated rationalization for keeping these drugs criminalized was their endogenous addictiveness, while the racial and ethnic associations were kept veiled during anti-drug public relations campaigns.

Stories, such as Reefer Madness, were told about people who tried a drug and instantly went insane. People whose lives were particularly good until that demon weed or devil syringe came around. And it was important to describe how good their lives were, because it had to be the drug that ruined lives and not underlying suffering leading to drug use.

Now, because these drugs ruined lives, we had to fight them like our lives were on the line. Local and state police focused more and more on the enforcement of drug crimes. This was famously depicted by shows like “Dragnet”, where the police were shown protecting the innocent from the depravity of those who had chosen to partake in these devilish chemicals. Their choice had led to insanity and addiction. And the (white, affluent) public needed to be protected. But did the approach even work?

Hughes et al.’s historical account of a heroin epidemic in Chicago between 1946 and 1949 describes how the response was to arrest any users or sellers of the drug. Once they had been arrested, sentencing for drug crimes was made more severe. This was well after the creation of AA and the expansion of addiction treatments. And as this community was majority African American, the epidemic was observed with disgust and helped to solidify racist stereotypes presented by the anti-drug propaganda.

But, once again, did it work? Hughes et al:

“…found the period of epidemic decline to be closely associated with increasing cost and decreasing quality of heroin available on Chicago’s illegal drug market. A dramatic response in…local enforcement practices and arrest rates, court sanctions and legislation, mass media attention to drug abuse did not occur until a year or more after the epidemic had already begun its decline.”

Which all means that the harsh enforcement of those laws was not the main driver in slowing the epidemic but did make for good television.

During the 50s, this ham-handed and severe enforcement occurred almost exclusively in African American and immigrant communities, much as it had been with the West Coast drug laws of the late 1800s and the anti-liquor enforcement during Prohibition. It stayed in those communities until the 1960s, as drug use expanded through the counter-cultural, hippie movement. While marijuana and hallucinogens (such as LSD and psilocybin) are usually recognized as the “hippie” drugs, the expansion included increased use of “hard drugs,” such as barbiturates and amphetamines, and even painkillers like heroin. The overwhelmingly whiteness of the hippie movement caused a certain panic round drugs that was easy fodder for talented politicians.

Addiction in America, Summarized

Up to this point, we have discussed connections between drugs and the larger culture, and how our society views addiction, as separate but parallel events. That all changed when Richard Nixon signed the “Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970”. It codified both the ideal of a culturally defined “hard drug”, as well as the ideal that the recreational use of drugs was an inherent evil, and those who used drugs at all needed to be treated for their disease of addiction.

While there had been skirmishes for decades between police and countercultures and communities of color, this was the first official salvo in the “War on Drugs”. This law was not just for the use or possession of certain drugs either. It also worked to control the manufacturing and sale of drugs. This was defined through the “Schedule” system, which we still use to this day. The system defines what level of legality a drug exists within at the federal level.

For example, Schedule I drugs (the highest level) include heroin, LSD, and marijuana (even though marijuana is legal in many states). Coming in at Schedule II are drugs such as OxyContin or Adderall, both of which are key figures in contemporary drug issues, such as the opioid epidemic.

Xanax, coming in at Schedule IV, can kill a person during withdrawal and also plays a major role in overdoses today, as it can be lethal when combined with high levels of an opioid. Yet Xanax lies well below marijuana on the scale, showing once again that the definitions of drugs have less to do with actual effects and more to do with cultural ideology.

So, what exactly was the goal of Nixon’s drug act? According to John Ehrlichman, one of Nixon’s domestic policy “chiefs,” “[t]he Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people.” A drug law that could make harsher federal crimes, and even allow for state forfeiture of property, was a good strategy to fight both those communities.

Ehrlichman went on to say:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities…We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.” (emphasis added)

What exactly were they lying about though? Partly, it was the rates of use in those communities. In fact, by 1970, when the law was signed, drug use was actually on the decline. Yet, when he signed the law, he stated it was in response to “growing heroin addiction.” As we saw in the Chicago Heroin Epidemic of the ‘40s, the harsh use of law enforcement did not create the conditions to lower overall use and addiction.

In many ways, they were also lying about the effects of those drugs, parroting earlier ideas about endogenous addictiveness as we saw in Refer Madness. And at this point, how was addiction defined anyway?

Six years after Nixon’s law had passed, the American Society for Addiction Medicine (ASAM) and the National Council on Alcoholism (NCA) convened and combined their separate definitions of alcoholism into a singular one. This definition was focused on “alcoholism,” as opposed to general addiction, due to the influence and prestige of the AA/alcoholism movement:

Alcoholism is a chronic, progressive, and potentially fatal disease. It is characterized by tolerance and physical dependency or pathologic organ changes, or both-all the direct or indirect consequences of the alcohol ingested.

Other than the singular focus on alcoholism, it is not dissimilar to what we see in the 2011 definition of general drug addiction from ASAM:

Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.

This concept of addiction is still focused on the use of the drug as catalyst for causing the primary disease. This use leads to changes in the body and brain, creating a condition where the individual cannot control their intake of the drug. Once they get to this point, it only makes sense to use any means necessary to stop them, and then try to fix them. And due to this evil inherent in drugs, as we stated before, it means we should take all steps necessary to protect ourselves from drugs and those who would sell us such poison.

But what if that definition isn’t true? What if the way we think about addiction is all wrong? What would that mean for all these policies and ideals we have held as a nation?

The disease theory of addiction had been ingrained in our culture for 200 years when Nixon signed this law. But had we ever actually checked to see if it was all true? In the next part of this series, we’ll look at a few studies that took up these questions in the same time frame as the Controlled Substance Act and the start of the War on Drugs.

Editor’s Note: All blogs in this series are available to read here.

” because these drugs ruined lives, we had to fight them like our lives were on the line. ”

Excellent article. You have put in an incredible amount of work into this.

As you have shown, the explanations as well as the resulting approaches to deal with the unwanted actions, feeling or behaviours have never been true, nor have they “worked”. In fact, they become worse.

There was a lot out there that could work, not then and not now is this palatable to politicians or the holders of big bank accounts.

Report comment