It took seven prior articles to review the process which established the American versions of addiction treatment, theory, and policy, to explain how Americans came to believe that addiction is a disease, that certain drugs are “bad,” and that we need to use punitive measures to “fix” people who are addicted to these “bad” drugs (even if they aren’t necessarily addicted).

To best understand why so many people are turning away from these ideas, we really just need to review how Patt Denning became a Harm Reductionist.

“Do no harm”

As she recalls in her guide to “Harm Reduction Psychotherapy,” Denning was working with a woman whose husband was suffering through an addiction to alcohol. Every night, her husband would immediately start to drink when he got home from work. Sometimes, he would drink to the point where he was not able to go to work the next day. Denning’s patient, who was already taking care of the house and the kids, would have to make an excuse for her husband’s absence from work. That way the husband could maintain the family’s income, but at what expense?

Denning, who at that time considered herself to be more traditional, told her patient that this relationship was “co-dependent,” and that she (the patient) was just as addicted to her family’s condition as her husband was. Denning told her patient to move on from her husband and allow him to hit “rock bottom.” The old theory goes that only once a person has hit this lowest point will they then gain the motivation to recover.

In addition, Denning told her patient that she should go into an “Al-Anon”-based treatment program, which is a 12-step group for people suffering from “co-dependence.” This group was formed by AA Founder Bill Wilson’s wife, Lois, who modeled it on the very problematic chapter in AA’s Big Book, “To Wives.” The patient took the advice, as anyone in her place would have. She, like Denning at the time, had no reason to not believe these ideas. So, she left her husband and started treatment for her “disease” of co-dependency.

Denning didn’t see the woman again for some time. Eventually she returned to Denning to continue therapy. She reported that her treatment program taught her that she needed to stop “rescuing” her husband when his drinking would cause him to miss work. She followed that advice, hoping that he would find his “bottom.”

This led to her husband losing his job, but it didn’t lead to recovery from his alcohol addiction. Now the family no longer had any financial means to survive and were dependent on welfare. While the patient was still maintaining the house and the children, she was also now in charge of finding and maintaining welfare and working for any other money that she could. The woman was grateful for the help that Denning had offered, but was now reporting increased exhaustion, insomnia, anxiety, and other “symptoms.”

Denning asked herself, “What help did I give her? Her day-to-day life was more dysfunctional than when I had first seen her, and she was clearly more distressed. I was haunted by the healer’s promise to ‘First, do no harm.’”

Denning came to realize that by pathologizing the behaviors that the patient was presenting (such as rescuing her husband when he would miss work), she was negating the adaptive elements of those behaviors. Yes, the patient was “covering” for her husband, but she was doing so to sustain her, and her children’s, lives. This realization has caused many people who initially saw addiction more traditionally to convert to following the Harm Reduction model.

Practitioners and researchers have increasingly started to feel that the maintenance of the status quo has been taking precedence over working to lessen suffering. This has left the addiction field in a state of conflict and fluctuation.

Where are we now?

When I was freshening up on my research for this project, I stumbled on an interesting event that had flown under my radar. As someone who has now spent two decades researching the etiology and ontology of addiction, the standard definition of addiction is of great interest to me. As was discussed in part 1 of this series, The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), who is the ordained authority over that definition, changed the definition of addiction in 2019. What was strange to me about this change is that I had no idea about it until I went to use the ASAM site as a reference for that first piece. There, the definition that I had known for some time had been replaced by a much shorter and less rigid statement. For reference, here is the 2011 ASAM definition:

A primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.

And here is the 2019 version:

Addiction is a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual’s life experiences. People with addiction use substances or engage in behaviors that become compulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences…Prevention efforts and treatment approaches for addiction are generally as successful as those for other chronic diseases.

It is no longer just a brain disease, but a disease of “complex interactions.” The concept of “spirituality” has been removed. All the symptomology has been reduced to just “behaviors that become impulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences.” And instead of a veiled threat of disability or death without treatment, now the statement just relays the idea that treatment can be as helpful as any other treatment for chronic diseases.

After first reading that new definition a year ago, I went onto my social media accounts. I follow many researchers, reporters, and other addiction/harm reduction groups to keep up with the “happenings” under the addiction umbrella. But I could not find any major reporting of the change. It flew under most radars, almost as if the ASAM did not want to make a big deal of it. But why would they do that?

Well, what I see in the difference between the two definitions is a compromise between two quarreling camps. One is connected to the traditional ideas we have had for centuries. The other is refuting those old ideas and trying to build on the new ideas of recent decades. The last thing you want if you are the ASAM is for your announcement of a new definition to be picked up by these camps and end up in the middle of a proxy battle. The reality is that today, there is no consensus on how we define addiction, nor one to describe how best to treat it. The “field” has found itself at a crossroads.

A complex, multi-faceted phenomenon

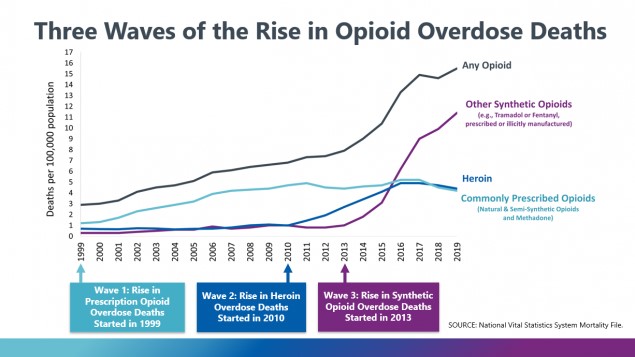

One driving factor in the advancement of Harm Reduction, and therefore the continued conflict within addiction research and treatment circles, has been the “Opioid Crisis.” For reasons that hopefully will become obvious, it could be better termed the “Overdose Crisis”:

Starting in 1999, an increasing number of overdose deaths occurred due to heroin and opioid use. The first wave was deeply connected to the introduction of Oxycontin, which is now a famous drug not just because of its connections to the crisis but also to its connection to the Sackler family. The Sacklers have been targets of many lawsuits connected to the crisis, and the specifically to the marketing of Oxycontin to the masses. Many of these lawsuits contend that the Sacklers drove their company, the makers of Oxycontin, to “overpromote” a drug that had addiction potential for their own profit.

Before this first wave could fully subside, a second wave of deaths directly related to heroin started in 2010. This wave has been correlated with changes made to Oxycontin—as it was redesigned to be abuse-resistant—and overall opioid prescribing patterns, which were curtailed in response to the first wave. As people could no longer easily access this and other opioids, they were driven to the low-cost, high-efficiency heroin, which could be found on the “streets,” as a replacement.

As heroin is not regulated, the dosage of the drug being taken cannot be truly accounted for, leading to the increase in deaths. People were not able to correctly account for the strength of the drug being taken, and would accidentally take much more than normal, leading to an overdose and, sometimes, death.

This wave was somewhat short-lived, because the number of overdose deaths directly linked to heroin was overtaken by those connected to synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, in 2013. Once again, these deaths were connected to the fact that the user of unregulated opioids could not predict what, exactly, they had purchased. Just as the deaths in the second wave were from people not being able to be sure of how much heroin they were taking, third wave deaths were connected to people not being sure of what they were taking. Instead of buying heroin, people were (and still are) unknowingly purchasing fentanyl, which is a thousand times as strong as heroin. As can be seen in the spike on the graph above, the past seven-and-a-half years have been extraordinary.

The unparalleled nature of this crisis has less to do with opioid usage (as opioid use has stayed somewhat steady since 2002) and more to do with people’s access to knowledge about the substance they are taking. For a comparison, imagine you are purchasing a single glass of wine. You expect that wine to contain a certain amount of alcohol, and that specific amount of alcohol will create a distinct level of intoxication, to which you are already accustomed. Now, imagine that the glass contained twenty times the alcohol you are used to, but you have no way of sensing that. The wine tastes the same, smells the same, looks the same. In this scenario, there is a good chance you would get sick, and possibly die, from ingesting this single glass.

Additionally, the crisis has arisen in mainly America’s “whiter” rural and suburban areas. Although previous drug crises have come with punitive crackdowns by the state on both users and dealers, in the current crisis, people are far more accepting of an empathetic, treatment-first approach to these sufferers. Researchers pin the cause for this on the race and class of those who are suffering. Unsurprisingly, it seems that the criminalization of heroin/opioid users of color is still rampant, especially in more urban areas.

That empathy for certain drug users has helped Harm Reduction agencies and outreach groups expand during the last decade. However, it is (usually) well-understood in American Harm Reduction circles that the disparities that have helped Harm Reduction grow cannot be ignored or allowed to continue. Institutionalizing Harm Reduction in US federal policy can help to expand the approach by leaps and bounds, but the fear is that it could come with a price. By entrenching Harm Reduction within existing power structures, those structures could be bolstered. It is exceedingly important that Harm Reductionists understand the roots of the issues they are working to alleviate. They must work to question the ideas that help to maintain the status quo, which drives many of sufferers into needing Harm Reduction in the first place.

Where do we go from here?

After spanning two and a half centuries of addiction theory, treatment, and drug policy, we finally discussed where we find ourselves today. The only thing left to discuss is where we go from here. What are the next steps? What must we do to ensure the reactionism of the ‘80s does not arise again? How do we contextualize the sociocultural issues that drive drug addiction and abuse? Before I give my thoughts on how the future needs to look, I believe it is important to explain why I care so much about this topic in the first place. In the next piece, I will do just that.

Editor’s Note: All blogs in this series are available to read here.

I worked at Cigna in the Alcohol and Drug Dependency Department in the 1980s. I also published two books on alcoholism which discussed the Twelve Step articles of faith and the lack of empirical support. At the time, most of the work force were people in AA. This has changed dramatically. Of course, Bill Miller and motivational interviewing had an impact. But, I think the biggest impact has been the opioid epidemic. I attend the SAMSHA supported Providers Clinical Support System which intends to provide guidance to those who are providing methadone and buprenorphine to those with opioid addictions. What is surprising is that none of these people are in recovery and they don’t even mention Twelve Step programs. SAMSHA also funds peer support. I have many social work students who are also peer supporters. Although these peer supporters often are in Twelve Step programs they don’t object to methadone or buprenorphine. What a change.

Report comment

A couple of years ago I attended the “Science Writer’s Boot Camp” sponsored by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions which featured a talk by Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which is part of the NIMH. Dr. Volkow showed us a graph depicting the availability of “medication-assisted treatment” by year, and a few minutes later she showed us one depicting overdose deaths rates by year. Only one person there was impertinent enough to point out the two graphs tracked each other almost perfectly.

https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bs-ed-disease-model-20170304-story.html

Report comment

Wait, you mean encouraging people to KEEP using drugs instead of quitting led to more overdose deaths? How can that BE, Patrick? It is SO counterintuitive! /s

Report comment