Let us be honest. 2020 will be remembered for decades, maybe centuries, to come and not for reasons for which we should be proud. We are facing a convergence of crises. Our public health institutions are finding it increasingly difficult to control a pandemic. Our justice system’s institutional racism has been exposed. And our economic system has been questioned, as some of our poorest citizens are now seen as essential to society (without a raise, mind you). Historians, social scientists, and journalists will be able to build careers and dissertations on these crises for years to come.

While there are many connecting threads for these crises, there is one that is easy to overlook. This is how our culture perceives drugs and drug addiction. Our views of drugs and drug addiction obviously help to create our standards for treatments and diagnosis, while also helping to drive policy at all levels of government. Our fears about drugs and drug addiction have allowed our society to accept court mandated treatment and the continuing militarization of police, all the while pulling money from social services and using it to fund more law enforcement, even at the risk of our own ill health.

Models of Drug Addiction

The traditional view of addiction is what is known as the “Brain Disease Model of Addiction.” This model posits that persons who suffer from drug addiction have a “disease” which affects the neurochemistry of the brain, causing obsessive use of psychoactive chemicals, even when that use leads to unhealthy outcomes. The American Society for Addiction Medicine’s 2011 definition of addiction is:

“a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviours. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioural control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviours and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death” (emphasis added)

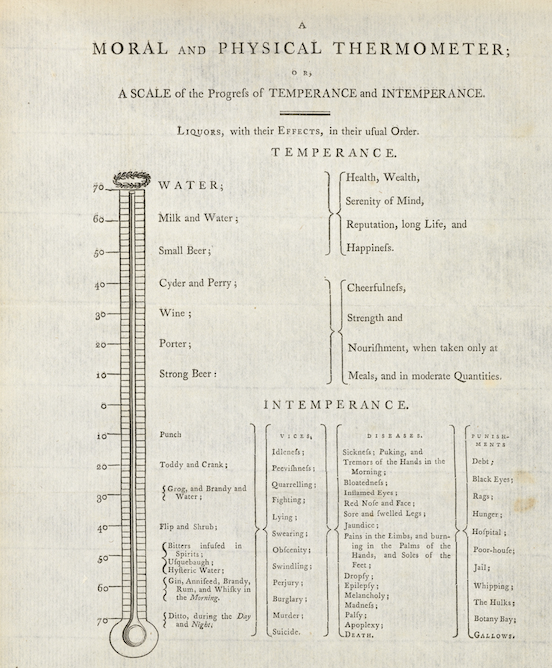

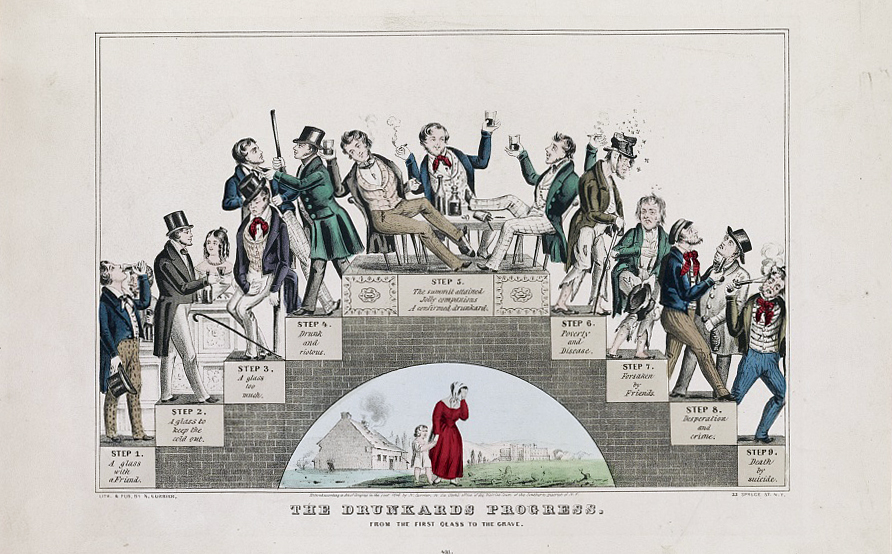

This model was originally rooted in the idea that certain drugs are “endogenously addictive” and this endogenous addiction causes the brain disease. Our current understanding first developed around the late 1700s, when physicians (such as Benjamin Rush) started to believe that alcohol was one of these endogenously addictive drugs. This spurred the creation of the “Temperance Movement” of the 1800s. This movement’s goal was to eradicate all drinking, period, as they believed that, on a long enough timeline, any drinker would eventually become addicted. Once addicted, the drinker would inevitably fall into poverty and disease.

This idea, that drugs are inherently addictive, lives on in ideologies around drugs like crystal meth and crack. During a conference in 2010, the Hawaii Meth Project, which advocated against the use of meth, presented their “theme of ‘not even once,’ [where] TV commercials portray users to be immediately addicted at their initial sniff, swallow or injection of the drug, leading to ugly physical consequences.” Even famous journalist Dan Rather quipped that “journalism is more addictive than crack cocaine,” using crack as a benchmark for endogenous addictiveness.

Since the public saw drugs such as meth and crack inherently addictive, policy makers sought to create public interventions to “eradicate” drugs from the streets. In the 1970s, President Nixon launched the “War on Drugs”, which was eventually escalated during the Reagan and Clinton administrations. This war locked up hundreds of thousands of Americans in an effort to chasten future drug users by setting an example with existing drug users and dealers. We also created treatment models based on the ideas of inherent addictiveness, and the permanent and chronic state of addiction that arose from using these drugs.

The most famous model/”self-help” group is, of course, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). AA’s biggest adaptation to addiction theory is “the idea that alcoholics constitute a special group who are unable to control their drinking from birth.” Instead of all users of addictive chemicals eventually becoming addicted, only a chosen few had a “predisposition.” Those who had the predisposition were now addicted for life, and need to abstain from ALL psychoactive substance, usually through the use of a “support group” such as AA or offshoots like Narcotics Anonymous, lest they fall right back into full-blown addiction.

Questions Arise

However, the last few years have seen a “war over addiction,” in which questions have arisen over the exact nature of addiction. This “war” is coinciding with a growing push to question the “war on drugs” and the treatments we use with people suffering from addiction. Some of these questions include:

- Is it actually a chronic condition akin to diabetes (to which addiction is often compared)? Recent data is showing more people can escape alcoholism and drink moderately without a full relapse than we ever thought, and ASAM’s 2019 definition of addiction removed the idea of “cycles of relapse and remission,” which they had connected to the idea of chronicity.

- Who is predisposed to “addiction” and why? Could the environment play a larger role in addiction, even when it comes to genetics and predisposition?

- Does the “Brain Disease” model lessen, or does it actually increase, stigma? Could teaching this old model actually harm people by causing them to think they are unable to control their own behaviors?

- Is using incarceration helpful for stopping drug use and addiction? And why do we have racial disproportions in who is incarcerated for drugs, when we know there isn’t the same disproportion in drug use?

Answering these questions is not a task that can be performed in a single article, unfortunately. Instead this will have to be done through a multi-part series that will attempt to answer these questions by focusing on different periods in American’s addiction history, and how those periods unfolded to leave us where we are today, starting with a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush.

Part I – “Ardent Spirits”

In addition to being a signatory to the Declaration of Independence, Dr. Benjamin Rush was also a pioneer in medicine before, during, and after the American Revolution. While known for his “Miasma” theory of disease, he was also recognized for Americanizing the ideas of epidemiology and public health, and he was a leading figure in what would become known as the “Temperance Movement.” While being a “man of science,” he was also religiously orthodox, “marked by faith in an absolute and heavily Calvinistic God.”

His religious beliefs, in which sin was forgiven through purification via salvation, led him to believe that diseases were cured and prevented by the purification of environments of miasmic elements. In other words, you would need to purify the air and water of the miasmic (aka smelly and undesirable) elements to ensure the environment didn’t cause harm.

As a trained preacher, he combined his verve for public health and “purifying” with his public speaking skills to spread his message of cleanliness to fight diseases. In this way, he was using what became the core element of public health: messaging and education of the public to decrease the existence of disease and other ill health.

He adapted this approach to the “revivalist tent,” in the very early 1800s, where he would also preach fervently against the use of “Ardent Spirits.” “Ardent spirits” was a term for beverages created via a distillation process (think whisky, brandy, etc.), that led to a high alcohol content. Rush and others would use revivalist camps to spread the idea that drinking ardent spirits would cause a disease to take hold within the drinker, who would no longer be able to control himself (men were the main focus of his studies, as they were the focus of most things during this time).

The first issue we have seen with the endogenous addictiveness of alcohol is that most people who drink alcohol don’t become addicted. The second problem was tied to a public health issue. During Rush’s time, there were no water treatment systems, so clean water was harder to come by. One easy way of ensuring a drink was sanitary was if it contained alcohol. The existence of alcohol within a beverage would ensure that the drink was safe. People knew this as a fact but were still a few decades away from being able to identify why, as “germ theory” had not yet developed. They did understand there was some form of impurity within their water, and that alcohol would cure this impurity, but could not identify the specific microorganisms that made people sick. The presence of alcohol would stop these microorganisms from growing, meaning alcoholic beverages could be safer than water.

Because the consumption of some types of alcoholic beverages was needed to maintain public health, Rush created a “temperance thermometer.” This “thermometer” was used to show which alcoholic beverages were “safe,” as opposed to “intemperate” beverages. Intemperate beverages were those that contained too much alcohol (i.e., ardent spirits). Intemperate beverages’ higher levels of alcohol would cause a person to become addicted. This was the effect of ardent spirits.

Now, a cursory examination of the theory does lend some credence to this idea that higher alcohol content would more likely lead to addiction. The stronger the beverage, the more intense the effects. The more intense the effects, the more intense the problems someone might have from drinking. In fact, there is something called the “Disruption Hypothesis,” which states that drinking “distilled liquor makes drunkenness easier and more likely,” leading to the belief that those distilled spirits were in-and-of-themselves the reason people would habitually get drunk.

Conveniently, Rush and others like him could use the Disruption Hypothesis to explain social ills as well. Rather than it being a pre-existing economic state due to inequality, Rush explained poverty as a result of ardent spirits and their effects on intemperate men:

“[L]et us not pass by their effects upon the estates of the persons who are addicted to [ardent spirits] Are they inhabitants of cities? – Behold! Their houses stripped gradually… to pay tavern debts… Are they inhabitants of country places? Behold their houses with shattered windows – their barns with leaky roofs…. Thus we see poverty and misery, crimes and infamy, diseases and death, are all the natural and usual consequences of the intemperate use of ardent spirits.”

Rush didn’t view the drinking of ardent spirits as an effect of the poverty he witnessed in the cities and countryside. He saw ardent spirits as the cause.

Here we can see a policy maker decrying poverty as an effect of drug abuse and addiction as far back as the early 1800s. Doctors were already explaining to the public that addiction to alcohol was caused by the choice to drink ardent spirits, and this addiction caused poverty. Even if the hope of the doctor was to create some sense of empathy, it’s understandable that those citizens would back the creation of “poor houses.” These houses were used to ostracize and marginalize the poor for being… poor.

If the persons who were sent to the poor houses were there because of the effects of ardent spirits, especially if they drank ardent spirits even after the travelling revivalists came to town to teach them about their ill effects, then wasn’t it really their own fault? Sure, they now had a “disease” that eliminated their choice, but hadn’t it been their choice to take the drink in the first place? And if that had been their choice, wasn’t it really their responsibility to find the will to get past this disease?

To show proof of the disease caused by ardent spirits, revivalists would search out people suffering from addiction and assist them in purifying their need for ardent spirits. Those in the Temperance Movement would use religiosity and “spirituality” to help people find total abstinence from alcohol.

In fact, if you’ve ever been to a 12-step meeting, some of these tools will seem pretty familiar. While we will discuss treatment models and AA in a later piece, it is important to see how this religiousness, specifically Protestant religiousness, connected to the idea of addiction as a “disease.”

Their Protestantism “[rejected] the idea that insanity reduced people to animals [and embraced] the idea of mental disease” (Foucault in Levine, p. 8). Protestantism, especially in the Temperance Movement, contained a “religious individualism.” This individualism lead to a belief in self-control, a trait needed to turn away from our natural state of sin and towards the enlightenment provided by God. So, Temperance Movement adherents would work with sufferers of alcohol addiction to learn self-control over their disease using the tenets of Protestant religion.

As part of the Temperance process to regain self-control, and to show others how important it was for people to admit their disease caused by ardent spirits, folks who had found their way through alcohol addiction were placed on the stage at these revivalist camps. People who had fought to gain back their morality and fight off the demons of ardent spirits were given the stage to tell their stories. One man, paraded for the masses, was John Gough. Gough became a “Temperance celebrity”, using striking oratory to explain his suffering and eventual salvation, which was found after becoming a member of the “Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society”:

Like many members of Temperance “recovery” and “support” groups (those two terms had not yet come into parlance), Gough used vivid, almost religious, imagery of his suffering and his ability to find the courage (usually through God, but not always) to slay his demon and become free of the effects of ardent spirits. His tale, like many others, was used both as a warning of the effects of ardent spirits and as a tale of hope for those already suffering from those effects.

Through the right lens, you can see a familiar story in this history—one that many people have already heard, whether personally, or through connections with others who suffered from addiction, or even in cultural artifacts like “People” magazine. We start with a theory regarding the endogenous addictiveness of a psychoactive chemical, yet that endogenous-ness was somehow not total (in this case, endogenously to ardent spirits and not to alcohol specifically). When it does happen, the inherent addictiveness causes a disease that ravages the body and mind, creating a person who can no longer temper their use of the psychoactive chemical. That person then suffers from poverty and ill health because of the disease of “Intemperance” (not yet alcoholism or addiction). All the while, the environment the sufferer existed within was only seen as an outcome of the disease, and not a possible cause. And in terms of the cure, the theory places the onus on the sufferer to partake in “self-help” to rid themselves of the condition.

Right at the time of the Temperance Movement’s “heyday” in the early to mid-1800s, there were ships full of immigrants from cultures tied to ardent spirits on their way to America. In “Part 2,” we will examine how the Temperance Movement reacts to these immigrant cultures, many of which had cultural connections to ardent spirits. Would it be able to adapt to these cultures? How would immigrants react to Temperance culture? And how would legislators acknowledge this growing movement, especially when faced with a rapidly changing nation?

Editor’s Note: All blogs in this series are available to read here.

Interesting blog, I’m looking forward to reading the rest of the history, as it’s something I’ve not really researched yet. I do want to read some of your links still, as they look interesting. Thank you, Kevin.

But as a Chicago gal, of course, I know about the ‘speak easies,’ and the Al Capone story. My family has owned a cottage Up North for generations, in a town where Al Capone’s brother had a bar, or ‘speak easy.’ It’s close to a restaurant where there was a shoot out between John Dillinger and the FBI. My great grandmother had bought our property from the former Cook county sheriff. So we have the shackles that the police held the prisoners, who built the roads Up North, on our property.

My great grandmother was a ward captain, or something like that in Chicago, which is how she knew the Cook county sheriff, and the first Mayor Daley. I always found it interesting that both the criminals, and the sheriff, were vacationing in the same small town. And my family has always joked that my grandfather put himself through dental school by bringing boot leg liquor from northern Wisconsin, down to Chicago.

I look forward to reading more about the history of the temperance movement, since it did affect generations of my family, actually. My dad left the Methodist religion as a young man, because they were still preaching that too much for his taste, as a young college kid. And learning more about the temperance movement does give insight into the “blame the patient” theology of our medical community.

“Their Protestantism ‘[rejected] the idea that insanity reduced people to animals [and embraced] the idea of mental disease.’” It may give the date in the link next to that comment, but I’ve yet to read that link in it’s entirety. Do you know, is this when the Protestant religions joined forces with the “mental health” workers? I’ve been looking for exactly when that happened, for a long time.

Since I’m very disappointed that my childhood religion – the ELCA – changed at some point, from being a Holy Bible / God worshipping religion, into a DSM “bible” / psychologist and psychiatrist worshipping religion. I do know the DSM “bible” came much later.

But I’m curious when, what an ethical Methodist pastor confessed to me to be, “the dirty little secret of the two original educated professions” – the psychologists’ and psychiatrists’ systemic child abuse covering up crimes for the religions – began? Do you know when that began?

The best I’ve found thus far is that the bulk of psychologists, psychiatrists, and their many “mental health” minion have really just replaced the witch hunters of old. But I’d like a more accurate understanding.

Again, thank you Kevin for giving us this relevant historical information.

Report comment

“Rejected the idea that insanity reduced people to animals…” Did it though?

The whole notion of “mental illness” is that those marked by psychiatrists are not fully human. Incapable of higher reasoning and completely amoral. Just like animals.

The “treated” are viewed as pets. The “untreated” as rabid dogs–either to be captured and rendered docile (helpless) or shot.

Report comment

The psychiatric worldview seems to imply that we are little to nothing more than animals. In fact, the psychiatric worldview probably disrespects even higher animals’ abilities to make decisions about their lives.

Report comment

Parading people around who have been “saved” from addiction thanks to “God” still happens today. A woman I met at the mental hospital had this very thing done to her. One of her family members threatened to kick her out unless she went through a one year Christian rehab program to become free of addiction. She wasn’t even allowed to smoke cigarettes. They made her give testimony in church groups full of “good” people to explain how this group and her faith had saved her, and how much better her life was now. After she got out, she went back to her drugs and cigarettes. They probably made her take psychiatric drugs in the “hospital” too, but wouldn’t let her do heroin.

Report comment

He isn’t familiar with the concept of addictive allergies to foods, where commonly consumed foods can lead to “addictive behavior” and thoughts, in addition to “psychiatric” symptoms. “Mental health” professionals don’t believe in them because they were described by Theron Randolph, who failed to impress the APA with his accounts of experiences with many of his patients, including a demonstration on stage of addictive/allergic reactions on stage, with several of his patients volunteering, to demonstrate their experiences.

Report comment

It’s paradoxical that the notion of “mental illness” discourages trying to better yourself. Just the opposite of what AA is supposed to preach.

Being told how hopeless I was as a “bipolar” led to my relinquishing self control. (Not alcohol but a psych drug that sent me on the bad trip that ruined my life.)

It’s also disgusting how opportunists are using the notion of “alcoholism is a disease” to push far deadlier and more addictive drugs on the person as a “treatment” for drinking wine or beer.

Report comment

An alcoholic is someone who drinks more than you.

There you go, cured. That’ll be $200 please.

Report comment

LOL, boans! Worth every penny.

Report comment

This article is highly problematic.

Psychiatry is pushing drugs as THE solution for “mild” forms of “mental illness.” In practice, nearly everyone with any complaint no matter the severity who walks in, or is forced in, to the “mental health” system gets put on drugs. Many become dependent on these drugs.

I don’t care if you call it “addiction” or something else. I have seen the personal stories of people trying to get off benzodiazepines (in the film Medicating Normal) and it a tortuous process that often takes years. We all should be aware of the addictive properties of street drugs, some medical drugs (opioids) and many common substances like tobacco, alcohol, coffee, and pot. And this article is suggesting we should drop our concerns about “addiction?” That it’s some sort of myth invented by Benjamin Rush? What? Whatever you call it, it’s a lived experience shared by millions of people!

The implication is that we should drop our concerns about addiction because the “model” is wrong. And this will lead to what? A wider acceptance for the use of drugs to “handle” conditions that have very little, if anything, to do with biochemical phenomena?

I have seen some characterize this pandemic as an “opportunity.” Exactly what do they mean by that? I know who has taken advantage of this “opportunity” so far: Those who want to frighted us into believing that there is a terrible danger lurking out there that only medical professionals know how to protect us from. Then the FDA does crazy things like allow test kits onto the market that don’t work, wasting millions of dollars that have flowed into the pockets of scammers and similar criminals.

Does this sound similar to the con game known as “psychiatry?” It sure does to me!

Report comment

“Does this sound similar to the con game known as “psychiatry?” It sure does to me!”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Shock_Doctrine

The documentary available on Youtube is quite good.

I think we’re all in for a bit of a “Shock”.

The world gives you lemons, make lemonade. And then have the government change the laws to ensure that everyone must consume lemonade on a daily basis, and if they don’t they will have the Tactical Response Group kick in their doors and ‘coerce’ them into drinking your lemonade (note, YOUR lemonade, not some cheaper inferior product produced in places like China).

Let’s see where the author goes with it, but yes, I agree with what you write.

Report comment

I_e_cox I agree with you. This whole scenario with:

1. Expert Doctor Monarchs who must never be questioned even when they contradict each other.

2. The Doctors/Demagogues who inflict their will over us all in the name of “our own good” or “for the public” who are never held accountable for bad advice.

3. It doesn’t matter if it ruins your career, your hopes of a family, renders you homeless, depresses you, or injures your physical health from months/years of isolation and stress. Don’t you ever dare quit distancing till Experts say you can. Maybe before you die.

4. Because obedience is all that matters the Experts are happy to throw you a bone every month or two so you won’t starve (hopefully.) Quit taking care of yourself. Self reliance is evil and wrong. Only eat what the Demagogue/Doctors feed you.

1. Never question a psychiatrist. Ever. This shows “poor insight” and doctors don’t make mistakes or lie.

2. Being forced to take drugs that make you miserable, tired and stupid is for your own good. And you owe it to society to be good pill popper or you endanger them by morphing into a mass shooter or something through non compliance.

3. It doesn’t matter if you feel horrible and can no longer read, work, get along with others, or attend to basic hygiene. It doesn’t matter if the pills give you grand mal seizures, heart palpitations, spasms, make you vomit uncontrollably for days on end, or put you into a coma. You must be “meds compliant” till you die. Doctor’s orders.

4. Because compliance is all that matters, once the “meds” have incapacitated you the Experts will sign a paper so their cronies in Washington will give you a pittance every month to scrape by on. The flunkies at the Mental Illness Center chastise you for wanting to be able to care for yourself. Shame on you for wanting to work. Besides that’s unrealistic cause you’re crazy. Lol.

De ja vu. 😛

Report comment

One of the main differences between alcohol, cigarettes, street drugs, and psychiatric drugs as I see it, is the the former are viewed as recreational and their potential dangers are acknowledged by mainstream society. Politicians want to stop opioid, alcohol, and cigarette addiction. Whereas, psychiatric drugs are culturally enshrined as legitimate medicine. True advocates for victims of psychiatry are publicly discredited, if they find a big enough audience. This isn’t surprising given that psychiatry specializes in discrediting and marginalizing people.

When I was a teenager, I was resolute in deciding that I never wanted to try illegal drugs, because it was my understanding that they could make you crazy. This despite peer pressure. If people knew the truth about psychiatric drugs, I feel that most people would never voluntarily choose to take them.

Report comment

just wanted to make a distinction between the official label war on drugs and what began decades before when Nixon was a fledgling no-name politician in California.

It may not have been given that specific name but Harry Anslinger a central figure in Hari’s ‘chasing the scream’, began a war on people who use drugs long before Richard Nixon sat behind the resolute desk. It’s an important point because labels given by politicians don’t define social or political or economic phenomenon. The facts do.

Report comment