In México, they’re known as abandonados, or the abandoned ones—people trapped, abused and neglected inside the country’s psychiatric system. Other words used to describe them are the olvidados (the forgotten) and dejados de lado (the left out).

Mad in México, which launched in September of last year, exists to make “los abandonados” heard. It aims to amplify those voices, empower them, embolden them—to wedge open the conversation surrounding mental health, knocking down the doors that seal off access in psychiatric, legal, penal, and academic institutions throughout the country and Latin America.

“We have to fight against that—and let these institutions know that they can’t get rid of us,” said Ilse Gutiérrez. “If they want to talk about madness… they will have to talk about us. Because we are part of that. We are not expendables. We are here.”

Gutiérrez was on a Zoom call with three Mad in México colleagues: Oscar Frarum, Víctor Lizama, and Luis Arroyo Lynn, who translated for the others. All four are participants in México’s Mad Pride movement. All four are also members—Gutiérrez and Lizama are founders—of the nine-person activist collective SinColectivo, which created Mad in México as one project in its broader campaign to fight injustice and advocate for rights across all systems and populations. The push for liberation of abused and oppressed peoples has a long history in Latin America, and it continues with the work of MIM and its overarching collective.

“Historically, the group of mental-health psychiatry survivors has been oppressed—from academia, from the institutions, even from other activists,” Lizama said. “So we believe that to reverse that, we need, first, to liberate ourselves from the inside—to open up to the outside. And this is the process of opening up to other discourses, other narratives, other experiences.” Or, as Arroyo Lynn put it: “We believe that no one should be subject to violence, that no one should be subject to oppression. . . . We deserve the right to be free.”

“And so we fight,” Frarum said.

Each has their own story to tell. Frarum has experience with suicidal desire, depression, and anxiety, gradually identifying as a person with psychosocial challenges and becoming an activist with SinColectivo and Mad in México. Gutiérrez, who spent 12 years on drugs with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, demedicated herself and embarked on the quest to make madness “visible”—embracing it while rejecting all stigma. Lizama, on his own path, took himself off antipsychotics after years of being medicated, isolated, and institutionalized—and now works for the Mexican human rights organization Documenta, where he coordinates a team of justice facilitators for people with psychosocial and intellectual disabilities.

As for Arroyo Lynn, he arrived at Mad activism as an ally, first witnessing the inner workings of psychiatric hospitals in his training as a psychologist: the bad practices and abuse, the overmedication, the horrors of electroshock, the “complete abandonment of the people that lived in those places.” Eventually, he came to realize “the farce that is the mental health system, the farce that is the institutions, the farce that is the diagnoses and the medications, the abuses of power that exist within those walls.”

Indeed, the mental-health system in México is notoriously overwhelmed and has a history of abuse and neglect. In 2010, Disability Rights International released “Abandoned and Disappeared,” a 94-page report detailing the institutional outrages endured by adults and children at facilities across the country. In 2015, it released two follow-ups: One on “torture, trafficking and segregation” of children, especially those with disabilities (México City has since banned restraints and cages); the other on the abuse and denial of sexual and reproductive rights among women with psychosocial disabilities.

The problem, say the Mad in México collaborators, is the lack of any true dialogue—or any recognition within institutions and academia that people affected by such abuse need to be heard. As the MIA affiliate explains on its “About Us” page: “Our priority is to make room for the experiences and knowledge of those who have directly experienced the effects of the ‘mental health culture’ and the hegemonic models of care.” Professionals aren’t excluded from dialogue, but they need to maintain that same, critical perspective on psychiatry and the current medical paradigm with the same regard for human rights.

The turning point in MIM’s origin story was the moment when, back in June of last year, the website formerly known as Mad in America Hispanohablante became Mad In (S)pain—and, seeing a gap in coverage for Latin America, Arroyo Lynn and his colleagues resolved to fill it. After a conversation with Mad in America, they decided to focus first on México, and from there form collaborations with other countries.

That was just six months ago. Assembled with no funding and running on the fuel of volunteers, the website is already packed with content, including translated articles from Mad in America; material reposted from other platforms; and original, first-person accounts of people with lived experience. In the Testimonials section, one writer describes his struggles with anxiety; another describes her nightmarish ordeal with benzodiazepines.

The idea, said Arroyo Lynn, is to “start to give voice to these people that have been voiceless.” That’s the foundational mission for SinColectivo and, by extension, Mad in México: “That people that live with all these struggles, all the discrimination, have a chance to raise their voices. Because who else will know better than the people that have lived it?” He calls this “the knowledge of the people,” and disseminating it—from a widely inclusive, widely accessible platform outside academia—is the affiliate’s chief aim moving forward.

That main objective breaks down into a to-do list of related goals. The first: solidifying and expanding the platform. Arroyo Lynn wants the site to have a bigger reach; he wants it to be taken seriously as a source for critical views; he wants students studying mental health to utilize it, people to rely on it, as “a primary source of information.” The second: “To start building a community—not only in México but in South America, in Latin America,” dissolving borders and creating “decolonized thinking in mental health.”

His colleagues and collaborators expressed similar hopes. Frarum sees the affiliate emerging, within the Hispanohablante community, as “a kind of library, or archive” that can be accessed by anyone—not just privileged individuals within academia. Gutiérrez concurred, emphasizing the need to “fight against the elite” and the institutions that barricade information from outsiders.

Access needs to be wide-open in both directions, they say. The goal is not just to share knowledge with all, but to glean knowledge from all—especially the people who, in Lizama’s words, “experienced the operation of the mental health system firsthand. Because that’s the only way we change the system.” Ultimately, he said, their input can and should influence the mental health system, the educational system, the legal and penal systems. All of it.

Although the site is only just launched, it’s showing early signs of impact. One: Some early comments saying “We should have something like this in Peru, we should have something like this in Argentina,” said Arroyo Lynn. Another: the testimonials and emails being received from people who want to share their stories or want to collaborate.

Readers are seeing themselves reflected in the content on Mad in México, he said—and they’re responding. At a recent screening of the new documentary Medicating Normal, commenters afterward spoke of their own lives and the decision, finally, to go off their psychiatric drugs. Arroyo Lynn and his colleagues at MIM hope to reach more such people and nurture, over time, a supportive network that becomes a true community.

“We have a lot of work to do,” Lizama said. “But in this moment, I think we are having a great start—and we are starting to find the ways that we want to work. We are starting to find our own mission.”

*****

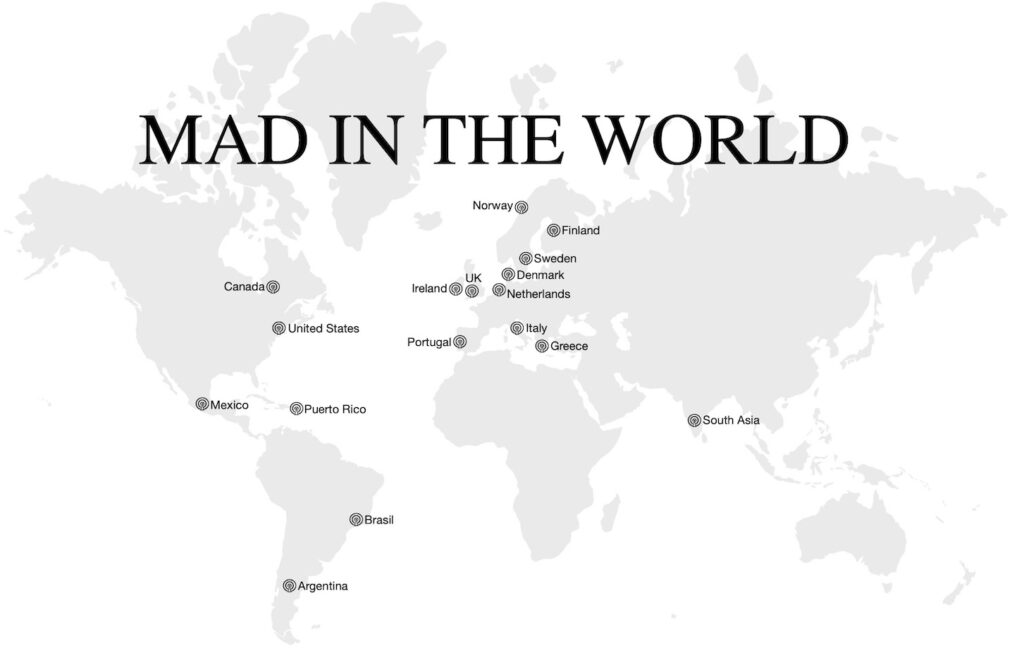

MIA Editors: Over the next 10 weeks, we will be publishing a profile of each of the Mad in America affiliates. They have banded together as a “Mad in the World” network.

Beans to born babies from Ukraine

Report comment