A new article published in the Brazilian journal Revista Direito e Praxis, titled “Human rights and psychiatric power in dispute: Towards a radicalization of democracy,” provides a history of the evolving debates over the human rights of people with psychosocial disabilities.

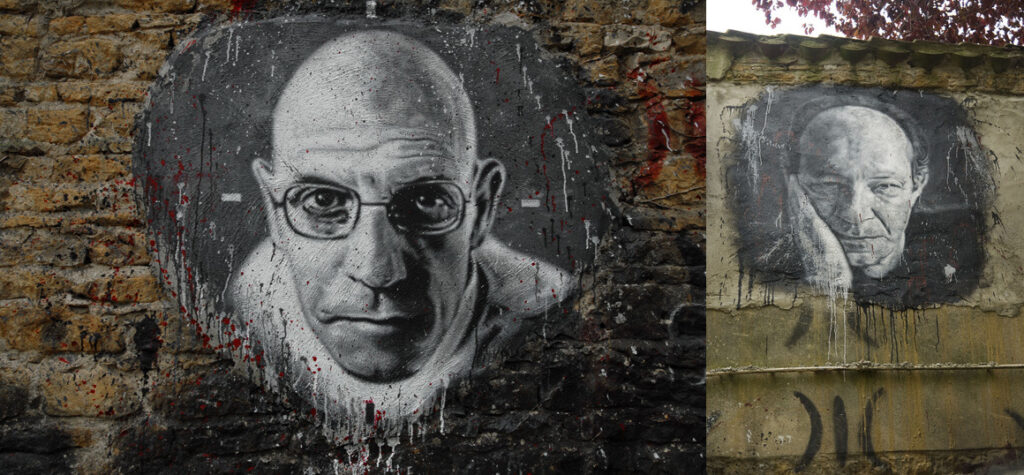

The Spanish authors from the University of Barcelona, Pérez Pérez, Margot Pujol I Llombart, and Enrico Mora, draw on the work of philosophers Michel Foucault and Giorgi Agamben to highlight the paradoxes of modern conceptions of mental illness and disability and trace them back through time. In doing so, they highlight the medicalization and creation of mental illness categories, critique past attempts to deliver rights to neurodivergent people, and explore the recent development of the Convention on the Rights for Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). They write:

“It is from this place that the CRPD is inscribed in a project of radical democracy that aims to recognize the multiplicity of the human. The abolition of forced commitment and treatment opens the possibility of imagining and deploying forms of support and accompaniment free of violence, de-medicalized, de-judicialized, and radically democratic for those who undergo experiences of intense suffering or madness, which increases their recognition as constitutive of the human.”

The authors operate at the intersection of Foucault’s concept of biopower and Agamben’s frameworks for sovereign power in four separate historically situated sections. Put simply, Foucauldian biopower is the tacit regulation, control, and surveillance of everyday life. Whereas sovereign power, according to Agamben, is distinct from biopower insofar as it is the legal and regulatory power that influences day-to-day life but also the power that identifies you as worthy of both civil and human rights.

Next, the authors explain the genealogy of psychiatric power and the contradictions found in Foucault’s earlier and later works. They use an allegory from Agamben to highlight how a loss of sovereignty (the revocation of human rights) subjects an individual to a life of increased surveillance and control. They argue that this made-to-die/made-to-live paradox is fundamental to psychiatry:

“The idea of the semi-living, moreover, resonates with the usual descriptions given by psychiatrized people in our contemporary world of the effects of high doses of neuroleptics, such as zombification, and also with its historical genealogy, as encapsulated in a ‘politics of indifference.’”

The authors highlight the emergence of the ‘psychiatric device’ and forensic medicine. The word ‘device’ in the phrase ‘psychiatric device’ is a challenging concept in translation from Spanish but can perhaps be more quickly understood in English as a kind of framework or theory in action. The authors trace both the history of ‘psychiatrization’ and the legitimatization of psychiatric frameworks over time. Importantly, they argue that the creation of the asylum has its foundations in the aforementioned “to make live, to make die” paradox. The authors then tie the values of psychiatry to the history of eugenics utilized by the Nazi regime during World War II.

“The function of degenerationist psychiatry was, according to Foucault, the ‘biological protection of the species.’ According to the matrix of biopower that he later proposed, this was a curative displacement (to make live) from an anatomopolitical sphere (disciplinary, based on the body-individual) to a strictly biopolitical one: what must be preserved is the life of the body-species, threatened by ‘degenerates,’ who are the enemy to be eradicated (to make die)… Degenerationism does not appear in his [Agamben] study, only eugenics, but his very apparatus allows us to understand why, after this pamphlet, the first centers of extermination in Nazism would be psychiatric institutions.”

Pérez and colleagues then contrast psychiatry with the emergence of “the human rights regime.”

“After World War II, the first human right formulated by the United Nations was that of non-discrimination on the grounds of ‘race, sex, language or religion,’ set forth in the Charter of the United Nations (1945) during the San Francisco Conference, which subverted what was agreed by the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union at the first Dumbarton Oaks Conference (1944). The second was the right to the ‘enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health,’ defined as ’a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,’ which was formulated in the preamble of the WHO Constitution, approved in July 1946 and effective as of April 7, 1948.”

However, they argue that the initial formulation of the “right to health” was closely connected to Nazi eugenics and perpetuated the sanism, ableism, and heterosexism of the regime. It wasn’t until the CRPD was created with both physically disabled and psychosocially disabled people at the table that the “right to health” truly became something of substance.

In particular, the authors draw attention to Article 12 of the CRPD, which requires states to recognize all persons with disabilities as legal persons capable of bearing rights and duties within both civil and criminal justice systems. The authors see this article as giving the previously lost sovereign power of the psychosocially disabled people back to them:

“It is thus understood that the mandate of Art. 12. fundamentally restores agency and freedom, sealing the threshold that separates the exercise of power over a free subject, which is intrinsic to any social relationship, from the exercise of domination over a human being reified and reduced to impotence, for having been constituted as bare life, excepted from the human right, and thus thrown into regimes of violence with impunity.”

Although the Convention on the Rights for Persons with Disabilities is a major improvement from past formulations and conceptualizations of disability and mental illness, the guidelines are only legally enforceable if adopted by individual nation-states. Unfortunately, the United States has yet to ratify the CRPD. In addition, research has reported that countries frequently invoke the CRPD in their mental health legislation and then push measures that run contrary to the intention of the legislation, like prohibiting involuntary commitment and forced treatment.

****

Pérez, B. P., I Llombart, M. P., & Mora, E. Human rights and psychiatric power in dispute: Towards a radicalization of democracy? Revista Direito e Praxis. DOI: 10.1590/2179- 8966/2022/65459i. (Link)

It must be nice to come up with these ideas whilst having the freedom to pick the fluff out of your navel. But the idea of actually bothering to look when someone makes an allegation AND has the documented proof…….. crickets.

“Although the Convention on the Rights for Persons with Disabilities is a major improvement from past formulations and conceptualizations of disability and mental illness, the guidelines are only legally enforceable if adopted by individual nation-states”

These ‘agreements’ have been adopted by Australia but aren’t worth the paper they are written on. Our Chief Psychiatrist doesn’t even recognise the legal protections afforded by the laws passed by our Parliament, and instead rewrites the law and utters with documents known to have been forged and produced as a direct result of acts of torture. The Fuhrerprinzip (Der Fuhrer Hat Immer Recht. The Fuhrers word is above all written Law)

“They wouldn’t do that” I hear you say….. have you bothered to look? I’m happy to share the letter where the Chief Psychiatrist removes the protection of “reasonable grounds” and enables arbitrary detentions….. and these are much worse than mere prison.

“In addition, research has reported that countries frequently invoke the CRPD in their mental health legislation and then push measures that run contrary to the intention of the legislation, like prohibiting involuntary commitment and forced treatment.”

I think you should include “involuntary euthanasia” in the list that runs contrary to the intention of the legislation. Such ‘treatments’ seem to be invoked for daring to complain about human rights abuses (“We’ll fuking destroy you”), and resolve the issue of the laws protecting the community being rewritten by our Chief Psychiatrist.

Don’t like the laws protecting the community? “edit” the documents after the fact, and start the ‘treatments’ on the victims complaining about being arbitrarily detained and tortured….. why bother, just snuff them. It’s not like anyone’s watching.

Report comment

“CRPD Debates Highlight Historical Tensions Between Human Rights and Psychiatry,” and until we all prohibit “involuntary commitment and forced treatment,” there will never be peace and justice on earth.

Report comment

I do wish MiA would bring back their edit option.

But I’d like to add to my comment, “Unless, of course, God chooses to judge all fairly now.”

Report comment

If people do not have the right for inherent pathology they do not have right to anything. Normalcy only gives meaning to particular pathology, and normalcy itself means nothing. Who are you ‘normal people’? Since the era of Enlightenment, identity is not identity anymore. Materialistic and spirutualistic escapes won’t save anyone from the truth, and the truth is like prophet – always near dead. Nazi, Anglo-Saxons, comunnists or technocracy won’t change it no matter how corrupted will be the thinking. There is archetypal coecion and things that ego is not able to control. Identity and its laws are superior to monistic claims. And false empiricism won’t change it still seraching for “the roots of mental illnesses. They mainly want to search for convenience or to simplify the psychological reality for the nedds of cult og ego without psychological and inherent influences. They want to straigten God. Or rebuke the gods.

“Consider the work of God: for who can make that straight, which he hath made crooked?”

I can put it much simpler : All Nazis should watch “Gatacca”.

Report comment