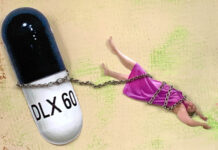

While tapering and limiting access to opioids has been a key strategy for dealing with the ongoing overdose crisis, new data shows that these policies may have the opposite effect.

A team of researchers at the University of California-Davis has been researching outcomes for patients whose physicians pushed a tapering of their stable long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) dosage. Using retrospective cohort studies, they have found that enforced tapering leads to an increased risk of overdose, mental health crises, and physical health concerns.

The research group, led by Elizabeth Magnan, a practicing physician and associate professor at the University of California, Davis, explains:

“Although cautious interpretation is warranted, these outcomes may represent unintended negative consequences of opioid tapering in patients who were prescribed previously stable doses.”

To find the longitudinal effects of medially managed opioid tapering, the team from UC-Davis pulled existing de-identified public data on health outcomes for patients who underwent tapering using OptumLabs Data Warehouse. According to the research team, “The database contains longitudinal health information on patients representing a mix of ages, races, ethnicities, and geographical locations.” This data is collected by collating medical and pharmacy claims submitted on behalf of both “commercial insurance and Medicare Advantage enrollees.”

To find the longitudinal effects of medially managed opioid tapering, the team from UC-Davis pulled existing de-identified public data on health outcomes for patients who underwent tapering using OptumLabs Data Warehouse. According to the research team, “The database contains longitudinal health information on patients representing a mix of ages, races, ethnicities, and geographical locations.” This data is collected by collating medical and pharmacy claims submitted on behalf of both “commercial insurance and Medicare Advantage enrollees.”

The research team used this information to perform multiple retrospective cohort studies to identify patients who had undergone this process and met their inclusion criteria. Each study identified patients 18 or older who had been on a regimen of at least 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) or more. For example, a person on four 10mg pills of oxycodone (aka Percocet) per day would have an MME of 60.

All cases included in the study were considered ‘stable’ on their LTOT, meaning they had not been in and out of treatment or had issues with substance use and opioid use disorder that interfered with their treatment. Everyone included had been steadily taking the medication as prescribed for multiple years. Each case included in the tapering cohorts had at least a 15% reduction in the MME. The team then identified patterns of service usage post-tapering for each person included in the study based on the claims in the data warehouse.

The first study looked to identify connections between tapering from LTOT and mental health crises and overdoses. The study included a cohort of 113,618 patients, including those who had undergone taper from PTOT and those who had not. In the findings, released on August 3rd, 2021, the team found that for “…patients [who were] prescribed stable, long-term, higher-dose opioid therapy, tapering events were significantly associated with increased risk of overdose and mental health crisis”.

For example, they found a statistically significant increase in overdose rates in patients who had undergone tapering (6.3 per 100 person-years) as opposed to patients who had remained steady on their LTOT (4.9 events per 100 PY). In addition, patients on LTOT who had undergone tapering were also at higher risk for mental health crises (7.4 events per 100 PY) than those on LTOT who had not undergone tapering (4.3 events per 100 PY).

The team followed up their initial study with an additional review to find the long-term risk due to the associations between tapering, mental health crises, and the risk of overdose. This cohort included 19,377 patients who had undergone tapering, and their usage of overdose and mental health services between 12- and 24 months post-taper was tabulated. This was then compared to their usage pre-taper.

After these results came in, the team stated that “…opioid dose tapering was associated with a persistently elevated risk of overdose, withdrawal, and mental health crisis up to 24 months after tapering initiation.”

This means that those who have undergone the tapering process have an increased risk of mental health and substance use-related crises for up to two years beyond the actual tapering process itself.

In a third study on the topic, released on February 7th, 2023, the team was trying to identify if there were associations between tapering from LTOT and physical health issues, including chronic condition control. The team pulled a cohort of 113,604 LTOT patients using the same data warehouse. Just as in the first study, the team compared those who had undergone tapering to those who had not. In this case, they were looking to compare each cohort’s number of ED visits, hospitalizations, and PCP and specialist visits.

The team also looked at blood pressure levels for those with hypertension and A1c levels for those with diabetes.

The team stated, “In this cohort study of patients prescribed LTOT, opioid tapering was associated with more emergency department visits and hospitalizations, fewer primary care visits, and reduced antihypertensive and antidiabetic medication adherence.”

In all three studies, the team found that there were associations between tapering from stable LTOT and increased health risks, including increased risk of overdose, increased rates of mental health crises, increased usage of emergency departments and hospitalizations, increased issues with chronic care conditions, while having decreased rates of contact with primary care physicians and specialists.

In a Washington Post article from 2019, Joel Achenbach and Lenny Bernstein interviewed Carla and Hank Skinner, chronic pain patients who had undergone medically enforced tapers. Who, along with other chronic pain patients (CPPs), felt “frustrated, confused and sometimes howling mad. They feel demonized and yanked around.”

There are growing fears, frustrations, and anxieties in the CPP community that they are becoming “opioid refugees” and collateral damage in the fight against the ever-expanding overdose epidemic in the United States.

Reactions to this epidemic have often been based on what is known as the “brain disease model” addiction, very much akin to the “medical model” of mental health. This is a highly contested and possibly outdated view of the causality of addiction, where-in certain drugs can ‘create’ addiction in people’s brains, even if they have no underlying concerns, such as trauma, poverty, or other mitigating factors. In this case, people with no history of drug abuse or addiction are being cut off from their medical treatment “just in case” they ever become addicted.

There is also an issue with confusing physiological dependence, where there is not always an emotional attachment to the drug, yet the body has become dependent on the drug for homeostasis, and addiction, which does not always entail physical dependence, but does contain an emotional attachment to the drug.

Additionally, there is also a push to replace opioid therapy with SSRIs. Yet, these medications do not produce the same effects as the opioid treatments that a CPP might already be on while also having their own long-term and physical dependency issues. Additionally, any analgesic effect of SSRIs is yet to be explained, which is of concern when this class of drug has had placebo-effect issues within its clinical trials.

While there is an ongoing problem related to drugs, overdoses, and addiction in the United States, any interventions must be based on the most up-to-date evidence. This includes ensuring the theoretical basis for any intervention is based on the most up-to-date research into addiction and mental health concern causality, lest the same patterns of over-correction be repeated ad infinitum.

****

Magnan, E. M., Tancredi, D. J., Xing, G., Agnoli, A., Jerant, A., & Fenton, J. J. (2023). Association between opioid tapering and subsequent health care use, medication adherence, and chronic condition control. JAMA Network Open, 6(2), e2255101-e2255101. (Link)

Fenton, J. J., Magnan, E., Tseregounis, I. E., Xing, G., Agnoli, A. L., & Tancredi, D. J. (2022). Long-term risk of overdose or mental health crisis after opioid dose tapering. JAMA network open, 5(6), e2216726-e2216726. (Link)

Agnoli, A., Xing, G., Tancredi, D. J., Magnan, E., Jerant, A., & Fenton, J. J. (2021). Association of dose tapering with overdose or mental health crisis among patients prescribed long-term opioids. Jama, 326(5), 411-419. (Link)

Are you aware of links between the university where this research was conducted and major pharma companies, such as Purdue and the associated Sackler charitable groups? Have you seen the allegations that this research group has previously received significant pharma support? Unquestioning consumption of research is always a problem – and I wonder if this would have been explored if this had been a piece in favour of SSRIs or other medications that seem to be disliked by Mad in America?

Report comment

The attempt to discredit by linking organizations like Federation of State Medical Boards, any pain advocacy organization, American Medical Association, etc. etc. to funding by Purdue is a tired, weak, knee-jerk response to any credible research that is trying to help the millions of chronic pain patients being harmed, many driven to suicide, by reckless, cruel policies targeting pain doctors and their patients. Why is there this insatiable blood-lust that seeks to inflict even more harm on people who are already suffering and have been debilitated by disease processes or catastrophic trauma like gun violence or other physical causes?

There was a time in America when the disability community garnered some amount of empathy and concern. Pain is the largest cause of disability nationally, globally. Now, those disabled by chronic, intractable pain gain attention only by being blamed for the drug overdose crisis which they have nothing to do with.

Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Dr. Nora Volkow said, back in 2016: “In any case, people with chronic pain are real victims of these shifting tides of medical practice, and we cannot forget about these patients in our haste to end the opioid misuse crisis. Health organizations are now taking steps to revise how we diagnose and manage pain in this country, but as yet, medicine has little to offer chronic pain patients in place of opioids.” “Physicians must understand that dependence on opioids is not the same as addiction ; and the potential dangers of restricting opioid medications on which patients are physically dependent could be devastating in the current drug landscape, where counterfeit pain pills made with the very potent opioid medication fentanyl are causing overdoses and claiming many lives.” https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2016/09/responsibly-sensitively-addressing-chronic-pain-amid-opioid-crisis.

Both Dr. Volkow and Dr Francis Collins, former director of National Institutes of Health, have reiterated the low percentage of people who get addicted.

Ethan Nadelman, founder of Drug Policy Alliance and Maia Szalavitz, one of America’s top authorities on addiction (permanent writer on the opinion staff of the New York Times) and one of those who challenges the “brain disease” model, have both stated the Purdue Pharma claim of 1% or less addiction rate among those w/o pre-existing vulnerabilities is ACTUALLY CORRECT. Dr. Volkow has said that among even those who have vulnerabilities (i.e. childhood trauma, previous addiction issues, etc) the rate of addiction is still only 8%.

The Nadelmann quote can be found in this link from Kate Nicholson, a former DOJ attorney and chronic pain patient who drafted the regs under the Americans with Disabilities Act : https://twitter.com/speakingabtpain/status/1462099939337637893?lang=en.

The Maia Szalavitz quote can be heard in this NPR/Dallas affiliate interview : https://think.kera.org/2023/01/24/cutting-people-off-from-opioids-may-not-be-the-solution/

Report comment

More proof that most doctors don’t know what they’re doing.

Report comment

I cannot understand how or why grown people continue to “believe” in fairy tales.

Just because a person gathers the resources to pay for a school that allows the government to add letters after their name does not necessarily turn them into an all knowing caring ethical superhuman being.

“Because I said so!” Should never be taken at face value no matter what “authority” says it!

Report comment