We have, to this point, reviewed 200 years of drugs and addiction in American history. In Part 1 we saw the genesis of the disease theory of addiction, and the temperance movement rise in parallel. This theory would then weave its way into American culture, helping to absolve forced cultural assimilation and encourage racism and stereotyping. We also saw, in the case of alcohol, how the theory can be adapted from all-encompassing, endogenous addictiveness to only affecting a “chosen few” predisposed to becoming addicted—especially in order to allow privileged cultures to continue to use their drugs of choice.

On the flip side, we also see how the theory can stay all-encompassing for those drugs we have criminalized, especially when those drugs can be used to continue to criminalize a culture. What we have yet to see is what happens if you test the theory. Regardless of predisposition, is addiction a chronic and progressive disease, marked by obsession and compulsion, which stems from changes to the brain?

The Robins Vietnam Study

It was not really until 1970 that this question was asked. And it was not even really being asked outright, as much as it was answered via circumstance. At this time, America was smack dab in the middle of the Vietnam War. Partly due to the Opium Wars of the 1800s, opium, and hence opioids, had spread from the Middle East down into the southeast Asian peninsula. This meant that cheap, potent heroin was widely available to America GIs in Vietnam.

Thousands of GIs started to use heroin freely, with many using to a point that would have crossed the diagnostic threshold of having an opioid use disorder (the DSM-5 diagnosis of either abuse or addiction to an opioid). The US government wanted to measure the impact that heroin addiction in returning GIs would have on the resources of the Veterans Administration. They tasked a group of researchers, led by Lee Robins, to quantify the problem.

In September of 1971, Robins’ group gathered a general sample of soldiers who were returning home from the war (about 470). They also took an additional sample of the soldiers who were returning who had opiates in their system when they enlisted (about 495). Of the General Sample, 43% had reported using heroin, with nearly half of those using the drug reporting that they became addicted. After a year back home, only 10% of the general sample reported using an opiate, and of those that did, only 7% reported readdiction to the drug.

As these questions were only researched after a year back home, Robins’ team did state that there were many follow-up questions that needed to be answered (i.e., how to measure the effect of setting on addiction, whether this is also true for non-military communities, how long the remission lasts). However, this data raises some important questions.

If heroin, unlike alcohol, has perfect addictiveness, and addiction is chronic and progressive, then those who used the drug must become addicted, and stay addicted. Actually, not just stay addicted but get worse. But what Robins’ team saw is something that traditional addiction theorists have stated is impossible: they found natural remission, where addiction is either “grown out of” or the person works through their addiction without formal treatment. Because not only did the GIs not stay addicted, but the majority did so without treatment. No 28 days. No 12-step meetings. No Lord’s Prayer. Just being removed from the hellish environment of war and coming back to the stability of home.

OK, so we see that the chronic and progressive nature of addiction is a bit wobbly. But what about the obsession and compulsion? Surely people who are addicted cannot control themselves around their addiction…Right?

Mark and Linda Sobell

While students at the University of California (Berkeley), Mark and Linda Sobell came to realize the same problem we described in the introduction: the disease model of alcoholism, and the need for perfect abstinence, had never been tested. To test it, they wanted to see if people addicted to alcohol could be “taught” how to moderate their drinking through behavioral treatments.

If a person could learn to moderate their intake of alcohol after becoming addicted to it, that would mean that a) treatments that focus on abstinence only would miss opportunities to work with people who were not ready or willing to adhere to abstinence, and b) that the theoretical foundation of alcoholism, and therefore the policies and practices traditionally accepted, would be incomplete at best.

The Sobells’ studies focused on “Gamma alcoholics,” which are those people whose intake of alcohol was much higher than normal, and their symptoms of withdrawal included delirium tremens (amongst others). This way, outcomes could not be attributed to the subjects not being fully addicted to alcohol. In other words, they made sure to study the “chosen few”, to quote AA.

The study had 70 participants, broken into two groups: a controlled drinking experimental group (n=30), which received the behavioral treatments, and the control group, who received traditional abstinence treatment (n=40). The researchers offered participants in the experimental group tokens and chits for performing tasks within the closed unit at Patton State Hospital, which they could “cash in” for a standard drink of alcohol. These subjects also underwent treatments akin to Cognitive Behavioral (CBT) and Rational-Emotive Behavioral (REBT) Therapies.

During the experiment, the Sobells noticed first that the experimental participants would not always cash in their chits immediately. Many times, they would hold onto the chits and store them up to use in a single day, while remaining sober for the prior days. This control and restraint by the “worst of the worst” alcoholics existed in opposition to the assumption of compulsion in the mainstream definition of addiction.

This restraint did not just exist within the controlled unit at the hospital either. After follow-ups at one years and two years, the Sobells found that the controlled drinking cohort was functioning better than the abstinence-only cohort, and, as they put it, “subjects could apply treatment principles to setting events not considered during treatment.” This meant that the behavioral treatments were more applicable to other areas of the subjects’ lives than the traditional treatment model.

Their studies would be greatly, and heatedly, debated during the 1980s and ‘90s (which will be reviewed in Part 6 of this series) but eventually their data was backed up by replication and other sources. This includes the 2014 release of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol Related Conditions (NESARC). The NESARC data showed that the overwhelming majority of those diagnosable with an Alcohol Use Disorder found recovery—usually through moderation and without traditional treatment. 40 years later, data was showing up that helped prove the Sobell’s studies that even Gamma alcoholics could learn to control their drinking without traditional treatment.

Taken together, the Vietnam and Controlled Drinking studies find that our 200-year-old preconception of addiction as a chronic and progressive compulsion and obsession with a substance just was not holding up to scrutiny. But while it may not be either of those descriptors, it obviously has to do with major and permanent changes to the brain…Right?

Rat Park

When I first started studying addiction in 2001, the Rat Park experiment by Bruce Alexander’s team of researchers at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver was a fascinating hidden gem that was ignored for years. It is a mind-blowing look into our misconceptions and assumptions around both our brains and the brains of rats.

Today, you have probably seen the Stuart McMillan cartoon, or the citations in Gabor Maté’s In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, or the TED Talk from Johann Hari, which all paraphrase the study. Even if you have, there is still more to discuss.

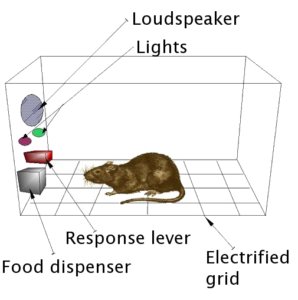

Let us start with how the study came about. B.F. Skinner, researching his Behaviorist theory of psychology, created the “Skinner Box”—a box where an animal can be conditioned to perform specific tasks, like hitting a button to get a reward, to cause the rat to continue the behavior.

One such study demonstrated rats’ susceptibility to drug addiction, specifically opiates and amphetamines. If the rat had two choices, a lever for water and a lever for the drug, the rats in the Skinner boxes would overwhelmingly pick the drug—even to the point of death by dehydration.

Alexander and his team realized that what might be missing is the rat’s natural environment. So, they created a controlled “Rat Park,” where rats could live amongst other rats, and do rat things like build tunnels and nests and have rat “relationships.” The rats in rat park were give the same choice between water and the drug, but rarely chose the drug. Alexander and his team believed that the natural environment and connections with other rats were able to insulate the rats from becoming addicted.

Now, to be transparent, there are problems with the study. It has had problems with replication, with some studies finding varying levels of use. There is also a problem with identifying a singular cause or solution to addiction solely within the environment, mainly because humans are much more complex than rats.

But isn’t that the point? In addiction circles, there is lots of talk about the dog brain, or lizard brain, or rat brain, all of which are parlance for the “lower” areas of the human brain. The assumption is that drugs “hijack” these areas of the brain, leading to addiction. These lower areas are basically the totality of brain power afforded to rats. But if rats aren’t always hijacked by drugs, and environment can play a role in addiction, then why should we believe that humans are hijacked by those same drugs? If (some) rats’ brains are not permanently changed, how could human brains, with their upper cortexes and unrestricted plasticity, be hijacked?

Love Addiction

During this time, and as a result of these new studies, Stanton Peele wanted to change the way we viewed addiction. Realizing that the old model had focused on reductive biology and the effects of the chemical aspect of the drug on the brain, to no avail, Peele wanted to move into an expansive view of addiction. Informed with both the traditional models and the groundbreaking new studies, he wanted to create an experiential definition and general theory of addiction. In fact, through this lens, addiction did not have to have anything to with drugs.

For Peele, addictions could be found in almost all aspects of life. In his groundbreaking book Love and Addiction, he starts with comparisons between the symptoms of drug addiction and the feelings associated with passionate, yet dysfunctional, relationships. These relationships are thrilling and meaningfully fulfill immediate needs when they start, but after time they take more than they give. Yet many people cannot leave these dysfunctional relationships, hoping that if they stick it out they can get what they once had. Even when they do break free, it is not without mourning, sleeplessness, anger, anxiety, and a whole host of other symptoms usually associated with drug withdrawal. Yet, there was no chemical directly impacting the brain.

He realized that humans could become addicted to any intense experience. Relationships, sex, food, gambling, work, money, power. They are all addictive, and do not have the same chemical interactions as drugs. Additionally, he offered a more existential and all-encompassing definition of addiction:

“An addiction exists when a person’s attachment to a sensation, an object, or another person is such as to lessen [their] appreciation of and ability to deal with other things in [their] environment, or in [themselves], so that [they have] become increasingly dependent on that experience as [their] only source of gratification”

We can now see addiction as a human experience beyond just the ingestion of a psychoactive chemical. Additionally, if addictions are existential and not biological at their core, then we can start to understand why addiction is not always chronically and progressively compulsive and obsessive. Addictions can diminish with environmental alterations and self-advancements, and their effects on the brain are not permanent, with plasticity of our cortexes allowing for new neuropathways to develop overtop the old. Addictions, while terrible and threatening, do not make us zombies.

What to do….

In the 200 years that the nation had existed to this point, many social and cultural issues were wrapped up in or defended by this idea of endogenous addictiveness of (certain) drugs and alcohol. This enforced the need for harsh punishments and somewhat brutalizing treatment. So, what should we do with the new information contradicting these theories? If they are all wrong, or incomplete at best, we would have to adapt, right?….Right?

In Part 6 of our series, we will study the 1980s and ‘90s to see exactly how we responded.

Editor’s Note: All blogs in this series are available to read here.

Excuse me, but it’s a “minor” turn off that the temperance movement did what!? If that could help stereotyping that’s a Fable to me. To begin with, 1 )you take away a person’s environment to find out by themselves what something does to them: temperance isn’t going to do that, that’s little doses to keep a person guessing till they’ve been told 2) then there’: they can’t find out what something does to them and keep doing it, thanks to “temperance” 3) not everyone is the same, people have different reactions to different things, how are they going to find out by themselves 4) I have to put something here as four, so why not add that it might change the size of vital organs, not the brain or anything like that, but the ones that are thought of most often 5) and we’re back to the scarlet D!

Report comment

Agree 100%. The problem lies, in my opinion, with 1) those who uncritically adopt the medical model thinking it makes them humanitarian and enlightened to do so, 2) the implicit Calvinism in Anglo-American culture; it always seems to find a way to reframe things in moralistic and punitive ways, and 3) regnant neoliberalism, which always seems to favor technological solutions which can be monetized.

Report comment

“Regardless of predisposition, is addiction a chronic and progressive disease, marked by obsession and compulsion, which stems from changes to the brain?”

Not likely.

“If heroin, unlike alcohol, has perfect addictiveness, and addiction is chronic and progressive, then those who used the drug must become addicted, and stay addicted.”

Not likely. I was unknowingly given a “dirty opioid,” in conjunction with a non-“safe smoking cessation med,” actual dangerous antidepressant. And since the two had major major drug interaction issues, I learned quite quickly NOT to regularly take the “safe pain killer”/ dirty opioid.

“so we see that the chronic and progressive nature of addiction is a bit wobbly.”

I’m quite certain it is.

Our “preconception of addiction as a chronic and progressive compulsion and obsession with a substance just was not holding up to scrutiny.”

In rats, who psychologists and psychiatrists tend to equate with other human beings. How ungodly disrespectful can they be?

“The rats in rat park were give the same choice between water and the drug, but rarely chose the drug.”

And that’s how I got my God damned psychiatrist to wean me off his drugs, by performing well with my fellow “peers,” or as the ungodly disrespectful researching psychiatrists’ claim, fellow “rats.”

“The assumption is that drugs ‘hijack’ these areas of the brain, leading to addiction. These lower areas are basically the totality of brain power afforded to rats. But if rats aren’t always hijacked by drugs, and environment can play a role in addiction, then why should we believe that humans are hijacked by those same drugs?”

Maybe the psychological and psychiatric researchers should garner some insight into the reality that other human beings are more intelligent than “rats.” Since I’ve been able to make fools out of both psychologists and psychiatrists, who didn’t believe a woman could do such to them. Although, I only did such, after they fuc-ked the living sh-t out of me and my family.

I agree, “humans could become addicted to any intense experience. Relationships, sex, food, gambling, work, money, power. They are all addictive….” I also agree, “addiction is not always chronically and progressively compulsive and obsessive.”

“So, what should [the “mental health professionals”] do with the new information contradicting these theories? If they are all wrong, or incomplete at best, we would have to adapt, right?….Right?”

Yes, correct.

Report comment

But I will also say, I believe love is the answer instead, since you did bring up love. And stigmatizatiizdng people with the “invalid” DSM disorders, has nothing to do with anything other than hatred of your fellow man, or woman. And I’d like to see that hatred of your fellow human beings, by the DSM deluded, ended.

Report comment

The idea of a “love addiction” is so perverse to me… who hasn’t stayed up all night worrying after the fate of a loved one in trouble, or had a death in the family shake up your life for a long while? People who stay in relationships that are going sour aren’t necessarily “addicted” any more than people who stay in therapy that fails are “addicted.” How in the world did we get to this point where every negative human experience is a pathology that needs clinical support instead of a form of human pain that peers can help with through community education? Isn’t public health fond of education as preventative? So let’s teach people kindness and peer support at a national level. We don’t need to stigmatized people for anything else.

Report comment

We should never compare humans with rats because

it really makes humans look badly.

Report comment